PSA testing in men without symptoms

Dr Ed Warren

Dr Ed Warren

FRCGP, FAcadMEd

Prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing is acceptable and offers opportunities to diagnose and treat cancer early – but not all men with a positive test result will have or go on to develop prostate cancer. What should we do?

CASE STUDY

Gerald is 52 years old, and is not seen much at the surgery. He calls one day in an agitated state and says he must see a doctor as soon as possible. On questioning, it appears that he has been looking at Stephen Fry’s website, and watching the video about how his prostate cancer was discovered during a ‘routine check up’ when he had his Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) level assessed. Stephen says ‘all men should know their risk’ for prostate cancer, so Gerald got a home PSA test from Amazon and sent his blood sample off. After 5 days he was contacted to be told that his PSA level was 3.5 ng/ml and that he should get an appointment with his GP without delay to discuss a hospital referral. He apparently has no symptoms that would make him fear that he had prostate trouble.

CELEBRITY ENDORSEMENT

Celebrity endorsement is used to promote all sorts of causes and to sell all sorts of products. It has also been used to promote healthcare messages, and it apparently works. The Hollywood actor Angelina Jolie wrote a newspaper article about her decision to have bilateral mastectomies based on her genetic risk of breast cancer. A subsequent study noted a 64% increase in BRCA testing in the US.1 Stephen Fry’s video has been posted on the Prostate Cancer UK website,2 and presents prostate cancer as a silent and lurking killer which is likely to strike you down without warning unless you get tested and catch the ‘aggressive little bugger’ early. The reality is a touch more nuanced than this. Amazon sells several testing kits for PSA, from about £7.50 to more than £50 a go.3 Some offer a phone-line to deal with any questions and queries, others do not. It is hardly surprising if Gerald feels he has acted responsibly by arranging a test for himself. And he hasn’t even asked the NHS to pay for it.

To add to Gerald’s confusion, for many years the US Preventive Services Task Force advised all men irrespective of any symptoms to have regular PSA tests after age 40, whereas the NHS did not. Perhaps the NHS is just trying to save money at the expense of vulnerable old men? Now however the Americans have fallen into line and the recommendations on both sides of the Atlantic are broadly similar.4,5

‘SHOULD I HAVE A PSA TEST?’

The NICE guidance recommends a PSA test for men with:4

- Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), such as nocturia, urinary frequency, hesitancy, urgency or retention

- Erectile dysfunction

- Visible haematuria

- Unexplained symptoms that could be due to advanced prostate cancer (for example, lower back pain, bone pain, weight loss), and also (compounding the confusion)

- ‘Men older than 50 years of age who request a PSA test.’

NICE also says: ‘PSA testing should not be offered to asymptomatic men’.4 How do you make sense of this? How does Gerald make sense of this seeming contradiction? NICE passes the responsibility firmly back to the patient – present the evidence and let him make the decision. NICE recommends that the following pros and cons should be discussed:4

Benefits of PSA testing, including:

- Early detection – PSA testing may lead to prostate cancer being detected before symptoms develop.

- Early treatment – detecting prostate cancer early before symptoms develop may extend life, or facilitate a complete cure.

Limitations and risks of PSA testing, including:

- False-negative PSA tests – about 15% of men with a negative PSA test may have prostate cancer, and 2% will have high-grade cancer. However, it is not known what proportion of these cancers become clinically evident.

- False-positive PSA tests – about 75% of men with a positive PSA test have a negative prostate biopsy.

- Unnecessary investigation – a false positive PSA test may lead to invasive investigations, such as prostate biopsy, and there may be adverse effects (for example, bleeding or infection).

- Unnecessary treatment – a positive PSA test may lead to the identification and treatment of prostate cancers which would not have become clinically evident during the man’s lifetime. Adverse effects of treatment are common and serious and include urinary incontinence and sexual dysfunction.

Or, to paraphrase, ‘The choice is yours, but we will try and put you off by offering twice as many reasons for not having a PSA done as compared with having one done’.

The Cochrane organisation (previously Cochrane Collaborative) was set up in 1993 to do systematic literature reviews (currently deemed the best way of getting to the truth) of health care interventions and diagnostic tests. At present it boasts 53 review groups and 30,000 volunteer experts around the world. Cochrane is worth listening to. In 2013 it conducted the third of a series of reviews on the evidence supporting the use of PSA testing in men with no symptoms. Cochrane concluded that PSA screening does not reduce the chance of dying of prostate cancer, and that the harms associated with screening; ‘are frequent and moderate in severity’.6

This opinion is reinforced by work from the USA.7 PSA testing was introduced in 1986. Before this the incidence of new cases of prostate cancer was rising gradually. From 1986 to 1993 the incidence at least doubled for both black men and white men. Since then there has been a lessening in incidence to about 150% of the 1985 level. The chance of dying from prostate cancer rose to a peak of 125% of the 1975 level in around 1993, and has been gradually declining since. There appears to be little correlation between the incidence of new cases of prostate cancer and the risk of dying from prostate cancer. This gap between diagnoses and deaths represents a cohort of men subjected to possibly invasive procedures, with the knowledge that they have cancer, yet with little chance that the procedures and treatments are going to do them any good, a situation that has been termed ‘too much medicine’.8

The cynic might argue that the American healthcare industry jumped on the new test bandwagon in 1986, aware that more tests, more diagnoses and more treatments means more profits, but that this cannot be maintained since everyone has now been diagnosed and made into a ‘patient’.

Does the knowledge of having prostate cancer upset men? Yes it does. The ProtecT study from 2016 concluded that the knowledge of having prostate cancer has more effect on men’s quality of life than the treatment of the cancer9 – this is quite a finding given that the treatments include radiotherapy and surgery which regularly lead to, at least temporary, incontinence and loss of sexual functioning. The psychological impact of a diagnosis of cancer is not just minor collateral damage in the management process. This is something which screening enthusiasts regularly ignore. The male ego is a thing of extreme delicacy, and the loss of sexual potency is not something to be trifled with.

PSA PRACTICALITIES

When taking blood for PSA, it should be remembered that things other than pathology can alter the level. For example, ejaculation lowers PSA by up to 85%.10 When taking a sample for PSA the NICE guidance recommends:4

Exclude active urinary tract infection (UTI)

Wait 4 weeks after a UTI has resolved (though the PSA can remain raised for several months).4 In over 80% of cases where a UTI causes fever, the prostate gland is involved.11 I could find no evidence that asymptomatic bacteriuria causes a rise in PSA, and so it is probably sufficient just to ask about the presence of UTI symptoms.

Should not have ejaculated in previous 48 hours

Most of the body’s PSA is in semen, and it is only the small amount that leaks out into the blood that is measured with the PSA blood test. Ejaculation suppresses blood PSA levels in the short term.

Should not have exercised vigorously in previous 48 hours

NICE does not specify a definition of ‘vigorous’,4 but one report showed a threefold elevation of PSA after 15 minutes of static cycling.12 In this particular study it is not clear whether the exercise and/or the prostate massaging effect of sitting on a bicycle seat were responsible for the PSA elevation.

Should not have had prostatic biopsy in the previous 6 weeks

Any procedure that attacks prostate tissue will cause PSA leakage. Presumably anyone having a biopsy will have had it for a prostate-related reason, and so your patient will not fall into the asymptomatic category.

Should be done before digital rectal examination (DRE)

A DRE is often offered as a means of providing supplementary information when investigating possible prostate pathology. So the best plan is to get the PSA done, and then get the patient back for the blood results, and to negotiate a possible DRE. This allows your patient time to get used to the idea of having a DRE, and, depending on the PSA result, offers the chance to avoid the DRE entirely. If the DRE is performed before PSA testing, wait at least a week

The sample should arrive at the laboratory within 16 hours

This is a logistics issue. Choose a day of the week for the test when the sample will get to the laboratory promptly, or alternatively, send your patient direct to the hospital phlebotomy unit for the test.

Other factors may affect the PSA level, and should be taken into account when arranging and interpreting the results of the test.

PSA levels are raised by:13

- Acute retention – in any event someone in acute urinary retention should be in hospital and it is silly to mess around taking blood samples

- Catheterisation

- Prostatitis, inflammation of the prostate usually caused by infection (sexually transmitted infection or a by-product of UTI), and

- Benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) – the virtually universal swelling of the prostate that occurs with advancing age in men

PSA levels are lowered by:

- 5 alpha reductase inhibition. 5-alpha reductase inhibitor drugs (e.g. finasteride) actually shrink prostates. They reduce the circulating levels of dihydrotestosterone by up to 80%,14 and this reduces the volume of the prostate by up to 28% after 6 months of treatment.15 They are used to treat BPH, and so are likely to be a feature in men of prostate cancer age.

How reliable is a single abnormal PSA test?

For many of the blood tests done in medical practice, it is recommended that the test be repeated as levels may fluctuate and there is a tendency for repeated tests to become closer to normal (‘regression to the mean’16). Also every laboratory has a margin for error in its testing procedures. Even grossly abnormal tests in the absence of other symptoms may not in fact reflect something wrong with your patient – remember the highly abnormal potassium results you get if the blood sample is left so long that the red blood cells start breaking down (haemolysis)? I cannot find in the NICE guidance any reference to abnormal PSA tests being repeated to confirm the level, even though PSA levels fluctuate both up and down. Nearly half of abnormal PSA levels will return to normal on repeat testing, leading to the eminently sensible suggestion that an abnormal PSA level should be repeated after 4 to 6 weeks,17 to see if it is really true.

WHAT’S THE BIG DEAL ABOUT LUTS?

Having concluded that doing a PSA in the absence of symptoms does more harm than good, what about the predictive significance of LUTS? Does the presence of LUTS make you more likely to have prostate cancer? Well, actually, no it doesn’t.

This is of course heresy, but the evidence contradicts the NICE guidance. NICE still has the presence of LUTS at the top of its list of reasons to start investigations for prostate cancer.4 To be fair, it is not the only item on the list, but it is right there at the top. The evidence does not support this view. Having LUTS puts you at risk of being investigated for prostate cancer but does not increase your risk of dying from prostate cancer. More cancers are found, but of the non-fatal variety.18 A small study from Holland also included patients with no urinary symptoms at all, and found that there was no relationship at all between LUTS severity (including complete absence of LUTS) and the presence of prostate cancer.19 If confirmed, evidence like this calls into question the prostate cancer case-finding strategy employed in the UK. Perhaps the Americans were right all along in screening all men, and the UK should have fallen in with them, rather than them with us.

The jury is still out, but there are various other factors to consider.

A diagnosis of prostate cancer is never confirmed just on the basis of LUTS or of PSA. There are additional pieces of evidence, to be rolled in with other confirmatory symptoms and with DRE and ultrasound and MRI. LUTS just gets the ball rolling (as it were).

LUTS is not always caused by a prostate problem. The differential diagnosis includes:20

- Urethral stricture (congenital, infective, traumatic, iatrogenic, malignant)

- Bladder cancer

- Bladder neck obstruction

- BPH – the vast majority of cases

- Drugs: (e.g. tricyclics such as the antidepressant amitriptyline; anti-muscarinics such as the atropine-like drugs that give you a dry mouth; and sedating antihistamines such as chlorphenamine, which can be bought over the counter so your patient may be taking it without you knowing as it won’t appear in the medical records)

- Sciatica or other neurological disease, and

- Prostate cancer

At least a third of men over age 50 have moderate or severe symptoms of LUTS,21 and presumably rather more have mild LUTS symptoms. So the presence of LUTS does not identify a particularly restricted cohort of men. Most LUTS occurs because of a prostate swollen because of BPH, and anyway the severity of LUTS symptoms is more closely related to the patient’s age than to prostatic volume.22

LUTS is invariably assessed subjectively. What men out there have never had to get up in the night for a pee? Does ‘urinary frequency’ mean ever having thought that you could do with urinating, or going to the loo so as not to get ‘caught short’ later? Indeed premature micturition might be regarded as a sensible precaution.

’Always make water when you can’

– Duke of Wellington

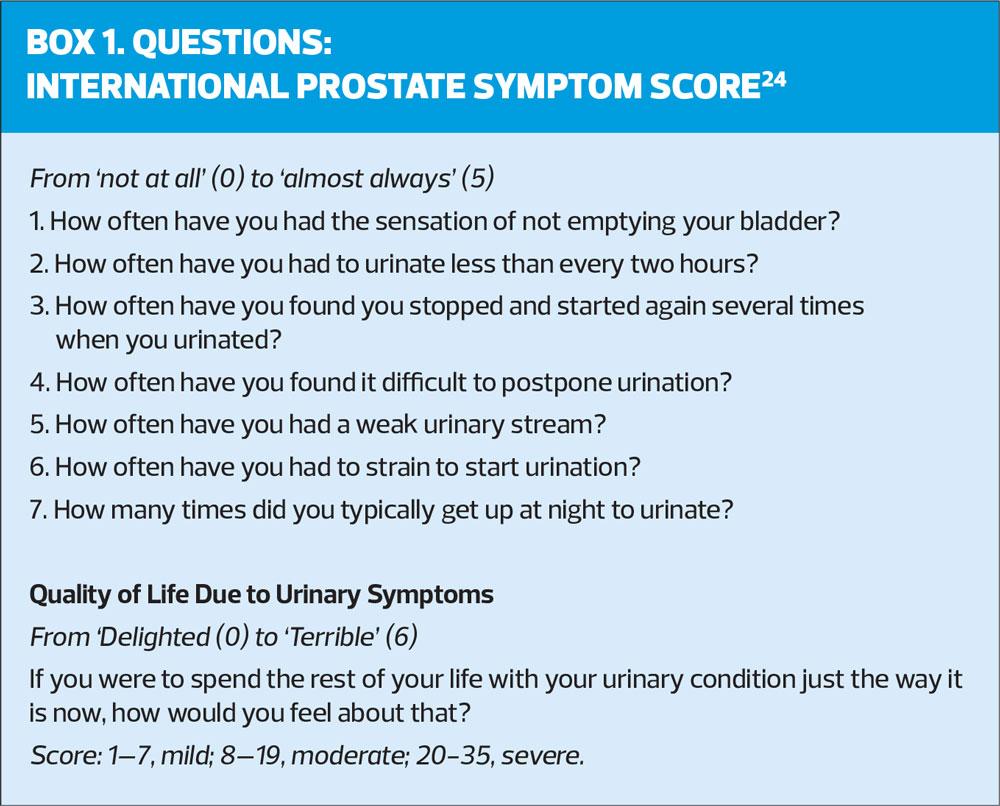

Sometimes a veneer of scientific credibility is attempted by the use of the International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS), (Box 1). However, you are relying on your patient to recall and respond truthfully. And when it comes to the quality of life question, the answers are highly subjective. Add to this the reluctance of men to discuss their urinary problems anyway, and it will be clear that the assessment of LUTS is far from reliable. Less than half of men with LUTS will seek help.23

It cannot be considered surprising if the presence of LUTS bears no relationship to the presence of prostate cancer. Prostate cancer nearly always starts at the outer margins of the gland, which is also why DRE is a useful procedure since the cancer can be felt. On the other hand the urethra runs right through the middle of the prostate gland, so any interference with flow, and any symptoms so caused, will depend on obstruction caused by lumps towards the middle of the gland. A prostate cancer would have to be of a significant size before it would distort the gland so much that a urethral flow impediment is produced.

So, looking at the evidence, you could well conclude that both PSA and LUTS are a waste of time as far as diagnosing prostate cancer is concerned. If you are answering an exam question, however, I would not recommend that you include this evaluation. What is the conscientious GPN to do? There are other candidates for ways to predict prostate cancer. A community survey showed that features predicting a higher chance of prostate cancer six months before the diagnosis is made are:25

- Weight loss

- Erectile dysfunction

- Urinary frequency

- Abnormal rectal examination.

Perhaps these would be more fruitful symptoms to enquire after. Screening DREs anyone?

CONCLUSION

There is no doubt that prostate cancer is an important disease, and in the UK causes thousands of deaths each year. Anything that can predict prostate cancer at an early stage, so that it can be treated, is to be welcomed. The existence of PSA testing – an acceptable blood test – offers promise that prostate cancer can be controlled. This has been reinforced by interest groups such as prostate cancer charities, and by several high profile celebrities sharing their experiences in the public domain. Unfortunately the reality is rather more complicated than just getting a blood test.

Testing for PSA in the absence of symptoms has not proved to be the boon once hoped. It remains an important part of the investigation armoury, but should not be regarded as of any more significance than that – with the caveat that the other ways of investigating possible prostate cancer may be less acceptable. In some respects, the current NICE guidance on prostate cancer has not kept pace with the developments in information about the disease. There are several powerful groups with an interest in promoting the use of PSA. As NHS primary healthcare workers we should be more interested in promoting the interests of our patients.

WHAT OF GERALD?

Because of his age and his PSA level, Gerald was referred urgently to hospital in accordance with NICE guidance. (The NICE recommended threshold for urgent referral in a man aged 50 to 69 years is a PSA of 3.0 ng/ml:4 at 3.5 ng/ml, Gerald’s level falls into the ‘danger’ zone). Within 28 days of referral he had had an MRI scan, and a prostate biopsy which led to a bit of bleeding and a fair bit of anal discomfort. Luckily all the investigations were normal, and it was agreed that Gerald should have a yearly PSA done at the surgery to monitor progress. Since his ordeal at the hospital, Gerald has been having occasional bad dreams, and is overly concerned about minor changes in his body. He has also developed erectile dysfunction.

REFERENCES

1. Ifrah S. The consequences of celebrity endorsements in health care. https://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2019/03/the-consequences-of-celebrity-endorsements-in-health-care.html

2. Prostate cancer UK. Stephen Fry calls for all men to know their risk after his treatment for prostate cancer https://prostatecanceruk.org/about-us/news-and-views/2018/2/stephen-fry-calls-for-all-men-to-know-their-risk-after-his-treatment-for-prostate-cancer

3. Amazon UK. PSA testing. https://www.amazon.co.uk/s?k=psa+testing&ref=nb_sb_noss

4. NICE CKS. Prostate cancer. Information about PSA testing. https://cks.nice.org.uk/prostate-cancer#!diagnosisSub:2

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate cancer: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/prostate-cancer-screening

6. Ilic D, Neuberger MM, Djulbegovic M, DahmP. Cochrane Library. Screening for prostate cancer (review). Cochrane Syst Rev 2013;1:CD004720 https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004720.pub3/epdf/full

7. Otis W, Brawley OW. Trends in Prostate Cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2012; 2012(45):152–156.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3540881/

8. Moynihan R. Costly and harmful: we need to tame the tsunami of too much medicine. https://theconversation.com/costly-and-harmful-we-need-to-tame-the-tsunami-of-too-much-medicine-48239

9. Cranston D. PSA testing: a personal view. Br J Gen Pract November 2019;69(688):562 p562. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X706361

10. Simak R, Madersbacher S, Zhang ZF, et al. The impact of ejaculation on serum prostate specific antigen. J Urol 1993;150:895-7.

11. Ulleryd P, Zackrisson B, Aus G, et al. Prostatic involvement in men with febrile urinary tract infection as measured by serum prostate-specific antigen and transrectal ultrasonography. BJU Int 1999;84:470-4.

12. Oremek GM, Seiffert UB. Physical activity releases prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from the prostate gland into blood and increases serum PSA concentrations. Clin Chem 1996;42(5):691-695

13. Dawson C, Whitfield H. ABC of urology: bladder outflow obstruction. BMJ 1996;312:767-70.

14. Shreeve C. Benign prostatic hypertrophy. The Practitioner 1993;237:619-23.

15. Simpson R J. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Br J Gen Pract 1997;47:235-40.

16. Morton V, Torgerson DJ. Effect of regression to the mean on decision making in health care. BMJ 2003; 326(7398):1083–1084. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1125994/

17. Eastham JA, Riedel E, Scardino PT, et al. Variation of Serum Prostate-Specific Antigen Levels. An Evaluation of Year-to-Year Fluctuations. JAMA. 2003;289(20):2695-2700. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/196625

18. í Jákupsstovu JO, Brodersen J. Do men with lower urinary tract symptoms have an increased risk of advanced prostate cancer? BMJ 2018;361:k1202 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1202

19. Blanker MH, et al. Prostate cancer detection in older men with and without lower urinary tract symptoms: a population-based study. JAGS 2003; 51(7):1041-42

20. Cahill D. The GP’s role in lower urinary tract obstruction. The Practitioner 2005;249:38-42.

21. Rees J, Bultitude M, Challacombe B. The management of lower urinary tract symptoms in men. BMJ 2014;348:25-28.

22. Williams G. Prostatic problems. Care of the Elderly 1993;5:265-8

23. Hunter DJW, McKee CM, Black NA, et al. Health care sought and received by men with urinary symptoms and their views on prostatectomy. Br J Gen Pract 1995;45:27-30.

24. International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS). http://www.urospec.com/uro/Forms/ipss.pdf

25. Hamilton W, Sharp D J, Peters T J, and Round A P. Clinical features of prostate cancer before diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:756-762.

Related articles

View all Articles