Clinical negligence: how GPNs will be judged

Elaine Biscoe, RGN, BSc (Hons) Nursing Studies

Independent trainer, Expert witness

The vast majority of care by general practice nurses is delivered expertly and safely but sometimes mistakes are made and allegations of negligence are brought. Expert witness Elaine Biscoe examines how such claims are decided

This article has been decades in the making because it has arisen from a culmination of all my experience in the world of general practice nursing.However, it is one particular role, acting as an expert witness in clinical negligence allegations against General Practice Nurses (GPNs), that has convinced me to share my experience.

Since my first job as a GPN in 1995, I have continued to work part time in various general practices.My career has also branched into offshoots, although all connected with nursing in general practice.I worked as a lecturer and also in primary care research as well managing a team of GPNs at a large practice.I then became the first National Advisor for practice nursing at the Care Quality Commission (CQC), a post I held for eight years.In 2012, I applied, via an advertisement in this journal, to be an expert witness and so began my journey into the medico-legal world.

In common with most nurses, I knew very little about the subject of clinical negligence and even less about expert witnesses.As a nurse, I have had possibly unique exposure to the variability of how general practice is run up and down the country and the implications for the GPNs.However, the cases I worked on as an expert witness showed me the reality of the avoidable harm patients can suffer when things go wrong and certainly made me reflect on my own scope of practice.As well as sometimes bringing me face to face with the patients who had suffered harm, it has also showed me the impact on the GPNs who faced the allegations.

My aim in this article is give a snapshot into the subject of clinical negligence and how nurses’ practice will be judged in the event of allegations being made – with the caveat that although through my career, I’ve seen the impact when things go wrong, most care is delivered expertly and safely by competent GPNs and most will never face allegations of substandard care.

CLINICAL NEGLIGENCE

Clinical negligence is the process by which a patient takes their medical attendant, for example, a nurse or doctor, to a civil court for compensation for harm that occurred as a result of alleged substandard practice.

If the claim is successful, the compensation awarded is designed to restore the claimant to the same position they would have been in, but for the negligence, obviously to the extent that this is possible. So if someone has to undergo a below-knee amputation, the award is intended to cover loss of earnings, therapy and treatment, transport, equipment, social care, adaptations to accommodation etc. Disabilities severe enough to require life-long care are obviously the highest value claims, for example, cases that involve avoidable harm to newborn babies as a result of maternity care.

Claims are funded by the NHS and so use resources that could otherwise be spent on patient care, so we all have a responsibility to minimise them wherever possible, and learning from these events is central to that aim.

NHS Resolution is the arm’s length body of the Department of Health and Social Care that deals with claims for compensation on behalf of the NHS. GPs, and the staff they employ, have only been indemnified by the NHS scheme, known as the Clinical Negligence Scheme for General Practice, (CNSGP) since April 2019.

NHS Resolution reports that in 2023/24, 2,382claims were received by the CNSGP, a 9% increase over the previous year.1 No figures are published on cases that relate specifically to nursing. In the scheme that covers secondary care, there were 10,834 claims.

Payments made by NHS Resolution in 2023/24 as a result of the claims from all schemes totalled £5 billion.This included damages and legal fees.Damages payments arising from general practice were estimated at £85million.

As well as being professionally accountable to work within the NMC Code,2 nurses are accountable in law, as are other professionals. Nurses have a legal duty to act carefully towards patients.Malpractice could lead to a civil action, or in extreme cases, criminal prosecution.Negligence is defined as an act or omission by a healthcare professional that deviates from the accepted standard of care and that has caused harm.

For a claim to be successful, there is a high bar that the claimant must clear.The patient (the claimant or their representative) must convince a court that the health care professional had a duty of care, which is usually straightforward as registered professionals have a duty of care towards their patients.They then have to prove that the care they received fell below an acceptable minimum standard.This is known as liability.Finally, they must also prove that, but for this failure, the harm would not have occurred, or not to the same extent.This means the failure has to be judged to have directly ledto the harm.The legal term for that is causation.

In my experience, unsuccessful claims have sometimes arisen when the patient has claimed a late referral led to the adverse outcome.It may be agreed that the referral was made late, so liability was proved.However, causation was not proved because the specialist expert opinion was that the delay made no difference to the outcome. It would have happened anyway.

TYPES OF CLAIMS

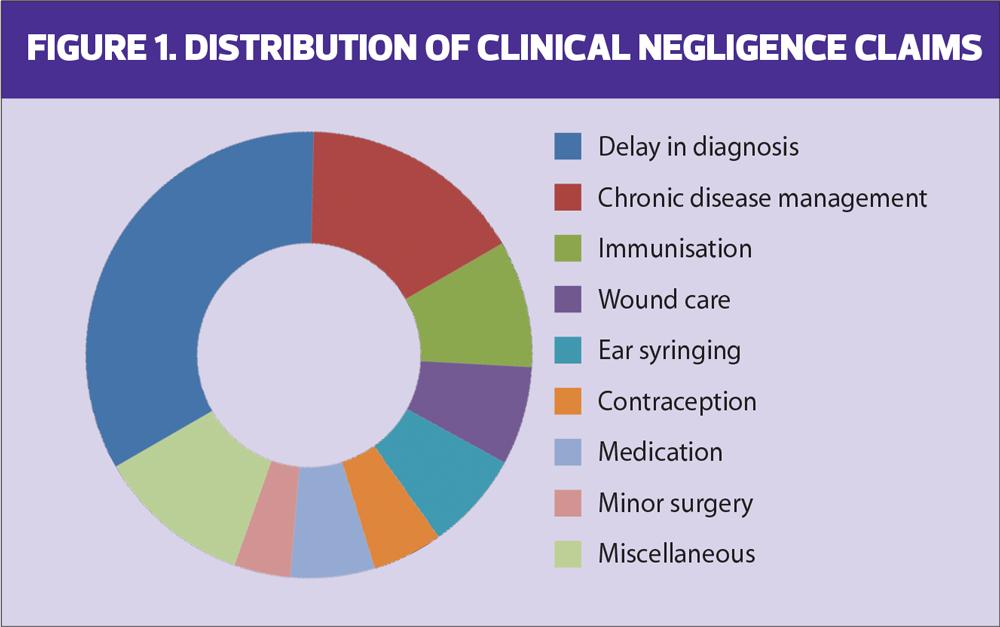

Medical Defence Union (MDU)* statistics show that missed or late diagnosis is the most common reason for claims against nurses.

The Medical Protection Society (MPS)* also found late diagnosis to be the most common reason for claims, followed by chronic disease management (Figure 1).Vaccination accounted for 9% of claims in the MPS study, which involved issues with the method of administration/technique and schedule.4

*MDU and MPS are two of the leading indemnity providers for healthcare professionals, including GPs and GPNs

In my experience, many cases arise from routine procedures such as injections and venepuncture.Examples of harm involve injuries caused by alleged inappropriately placed needles such as shoulder capsule injuries, loss of function due to needle contact with nerves and haematomas following poor venepuncture technique.

I have also seen many allegations of harm as a result of wound care, for example damage caused by inappropriate use of compression bandaging, missed surgical site infections and failure to refer for vascular assessment for non-healing wounds caused by arterial insufficiency.

WALKING THE TIGHTROPE

I believe that GPNs often walk a tightrope between demands of the job and working safely and within the NMC Code. Some of the inter-connecting reasons, based on my experience, that make GPNs vulnerable to pressure to work out of scope and in doing so put their patients at risk of harm and themselves at risk of litigation, are listed below.

FACTORS THAT LEAD TO GPNs WORKING OUT OF SCOPE

- Requirement for skills not learned in pre-registration training or other branches of nursing

- No mandatory entry-level training for GPNs or those working in an extended role

- Confusion over what training is needed and difficulty accessing it.

- Employment model leading to conflict of interest

- Variation in the role between practices and even within practices.

- No training or HR department

- Lack of availability of senior experienced colleagues

- Lack of understanding of the complexity of role by employer and management.

- Time-bound consultations.

- Unfamiliar IT system

- A relentless increase in demand from an expanding and ageing population.

As a way of progressing and developing their careers, many nurses take on roles as the first point of contact with patients, requiring them to make an initial diagnosis and plan.During CQC inspections, I asked many nurses working in this capacity about their training for this extended role.There was a huge variation in the responses, with many not having undertaken any formal, assessed qualification.It was also common to find, irrespective of their experience in a first contact role, there was no supervision with most relying on asking a colleague when they were worried.This places an acute responsibility on the nurse to know what they don’t know, sadly not always a reliable safeguard. During the pandemic, in my CQC role, I was regularly told about GPNs being expected to provide telephone triage for the first time, a notoriously difficult role, which requires different skills because of the absence of visual clues.

Of course, many nurses are carrying out these roles perfectly competently and are working in teams with excellent support from colleagues. However, it is worth remembering that doctors who decide to become GPs have completed additional years of training in addition to their medical degree to become competent in the complex clinical reasoning skills required.

No such equivalent mandatory training exists for nurses stepping into these roles.

THE STANDARD OF CARE

An expert witness is an expert who makes their knowledge and experience available to a court to help it understand the issues of a case and to reach a sound and just decision. Solicitors acting for both the claimant and defendant (nurse) will instruct an expert witness.The expert witness must not be influenced by which side is instructing them. Their role is to analyse the evidence and write a report giving their independent opinion on the standard of care given and whether it led to the harm alleged.

The standard of care does not mean perfection in practice, nor does it mean nurses can, or should, have been able to foresee the futureand eventual outcomes. It does not even mean the care of an ‘average’ nurse, which would by definition mean that care delivered by 50% of nurses would be negligent. It means the care must be minimally competent. For there to be a breach of duty, the claimant must prove, via the expert witness evidence, that no other reasonable and responsible nurse would have acted in that way.

Guidelines exist for many clinical areas, for example, chronic disease management, contraception and also referral criteria for common presentations.There may be perfectly good reasons why a particular guideline was not followed.However, GPNs who can justify their actions by use of current guidelines will generally be on safer ground than those who depart from them without logical justification.

Nurses whose roles in general practice include acting as the first contact with patients who present with undifferentiated conditions are working in a medical capacity and will be judged according to the standard of a reasonable doctor.A defence of inexperience or different level of training will not be an adequate defence from allegations of poor practice.

For an expert witness, the clinical record is often the sole evidence on which to base their opinion on the standard of care and it provides the same function for the healthcare professional if their care is ever questioned. This can happen years after the event.It is given significant weight by the court in terms of reliability.However, in my experience, its accuracy is often disputed by the claimant, for example whether safety netting advice was given.For GPNs working in a first contact capacity, the record should include relevant history and examination findings (normal as well as abnormal), differential diagnoses and steps taken to exclude them, decisions made and agreed actions, and information given to the patient.

Nurse practitioners might ask ‘if I get a diagnosis wrong, does that mean I’ll always be found negligent?’ Well thankfully no, we are not expected to have a crystal ball and primary care is all about managing uncertainty.The courts will not allow the benefit of hindsight to be used to undermine judgments about diagnosis that were carefully made at the relevant time. So a nurse cannot be criticised for failing to make a particular diagnosis, just because it turned out to be that.That is called hindsight bias.However, a nurse could be criticised for the absence of a focussed history and appropriate physical examination, based on the presenting complaint and for not checking for red flags relevant to that presentation.The following case study demonstrates this.

CASE STUDY

Record of consultation

- Leg ached on and off for two weeks since playing football

- Examination:

- Leg not hot

- No difference in calf circumference

- Tender to touch

- Full range of movement

- Diagnosis: muscle sprain

- Treatment: given Tubigrip

Background

A 46-year-old man presented to the nurse practitioner.A record of the consultation was made.

A week later, he collapsed after suffering a pulmonary embolism (PE).

He alleged breach of duty against the nurse for failing to take appropriate steps to assess and investigate his symptoms and that, but for this failure, he would not have suffered the PE.

Discussion

The nurse’s defence was that the patient reported a football injury.A Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) was ruled out by the lack of swelling and redness ,and justified the decision not to elicit any other history.In the nurse’s opinion it was obviously a football injury.

In contrast, the nurse was criticised by the claimant’s expert witness for failing to take a focussed history of the presenting complaint. Had they done this, they would, or should,have concluded that the history was not characteristic of a sports injury. There was no discrete mechanism of injury while playing football, but rather the patient remembered that this was when he first noticed the pain.

A full history would have revealed that he had been on a long-haul flight several days before the onset of the pain and was a heavy and long-term smoker.He was also overweight, all factors that raise the likelihood of a DVT.None of this was diagnostic of a DVT, which cannot be diagnosed clinically. However, the risk factors and lack of an alternative, more likely, diagnosis meant that it should have been suspected, and, according to established guidance at the time, a Wells Score calculated.5This would have indicated a D-Dimer blood test as the next step.

The claimant’s expert witness cited literature that some DVTs do not cause any symptoms and are only diagnosed when the patient develops a PE.Therefore, the absence of these symptoms should not have reassured the nurse.

In this case, it seemed clear that the nurse was unduly influenced by the way the problem was presented, a bias known as ‘the framing effect’.As this case shows, this can be very misleading and always needs exploring by a focussed history. The other failure was the ‘anchoring’ of ‘football injury’.6It led the nurse to jump to an early conclusion that was incorrect.

Outcome of the case

The judge was convinced by the argument that the nurse’s practice was below that of a reasonable standard and it led to the harm, soboth liability and causation were proved.The patient was subsequently awarded substantial damages.

CONCLUSION

The number of cases involving clinical negligence claims against GPNs only represent a small fraction of the number of patient interactions, although not all patients who suffer avoidable harm will make a claim.When it happens, the personal cost for the patient and their family can be enormous and life changing.There are also personal implications for the professional who has to face the allegations, and the cost of clinical negligence is a huge financial burden on the NHS.

The learning that arises from cases is a valuable tool for improving patient safety in primary care and this article has only provided a brief dip into it.There is also a wider message for GPNs and those with influence over how they work. Key to this is that the current ad hoc system of training and support for GPNs which often places them and their patients in a vulnerable position.Examining real cases provides a valuable opportunity for GPNs to reflect on their own practice, to set limits to it, as defined by their knowledge and competence, and to resist pressure to depart from this to suit other agendas.With this in mind, I am planning an e-learning module to include more cases and ideas for scrutinising practice.

REFERENCES

- NHS Resolution Annual Statistics. https://resolution.nhs.uk/resources/annual-statistics/

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code; 2018 (updated 2024). https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/

- Launder, M Nurse Practitioners face similar legal investigation to doctors, Nursing in Practice; 18 July 2022. https://www.nursinginpractice.com/latest-news/nurse-practitioners-face-similar-legal-investigations-to-doctors-say-indemnity-experts/

- Medical Protection Society. Rising Nurse Claims; 2017. https://www.medicalprotection.org/uk/articles/rising-nurse-claims

- NICE NG158. Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing; 2020 (updated 2023). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158

- Ly DP, Shekelle PG, Song Z.Evidence for Anchoring Bias During Physician Decision-making JAMA Intern Med 2023 1;183(8):818-823

Related articles

View all Articles