Flu vaccination uptake in the UK in at-risk groups: review

Simon Oakley,

Simon Oakley,

Julien Bouchet,

Paul Costello

Members of field based medical team, Sanofi Pasteur UK

Although the UK has one of the highest flu vaccine uptake rates in Europe, uptake among patients in the clinical risk groups is way below the ideal coverage of 75%. We look at the possible reasons and how uptake could be improved

Influenza is an acute respiratory illness caused by the influenza virus that anyone can acquire. Symptoms may include sore throat, cough, muscular pains, fever and weakness and can range from mild to severe. This article focuses on the ‘at-risk’ groups, as these patients tend to have a worse prognosis and outcome, paying particular attention to the current influenza vaccination uptake levels and considering strategies for improving coverage. The vaccine uptake target for at-risk groups is for at least 55% with the ultimate aim of 75%.1

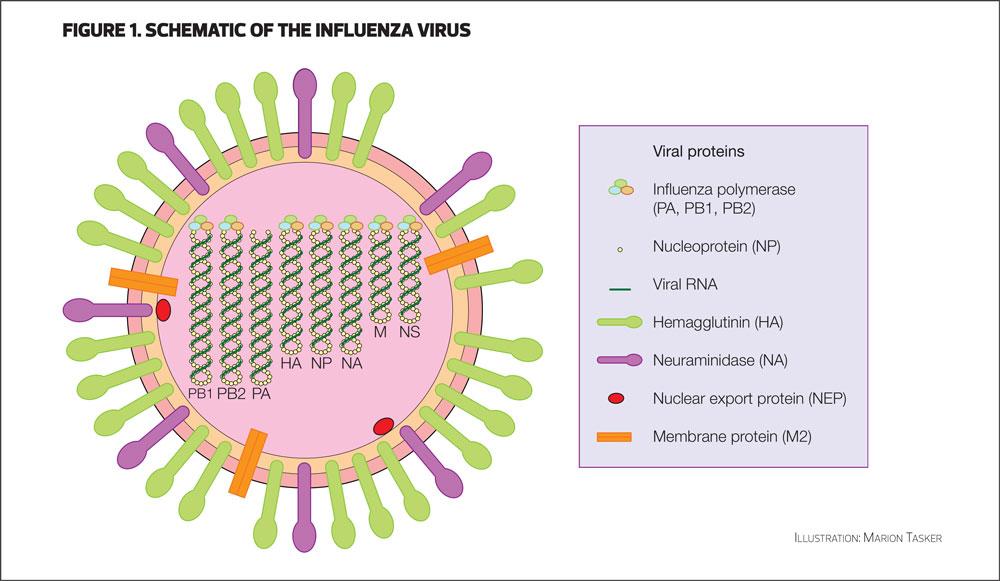

THE VIRUS

Influenza is an RNA virus of the orthomyxovirus family. The virus usually demonstrates a spherical shape, though filamentous forms have been observed. The RNA is segmented into eight pieces. The surface of the virus has two key proteins, haemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N), which are required for viral cell attachment and entry.

The virus was first isolated in 1933 and subsequently different types were described. There are four types of influenza virus: A, B, C and D. Influenza D virus is only recently described,2 and has thus far only been observed in cattle. Influenza C virus is found in pigs and dogs, and only rarely in humans. From a human perspective the most important are types A and B.

Type A is further classified into subtypes by the nature of the H and N proteins expressed on the viral surface (e.g. H1N1, H3N2 etc).3 There are 18 different haemagglutinin subtypes and 11 neuraminidase subtypes,4 and while type B is not divided in the same way, it does have two distinct lineages, Yamagata and Victoria.5 All of the major pandemics (e.g. Spanish flu, Swine flu) have been caused by influenza A subtypes: in recent years, influenza B – originally regarded as being responsible for more moderate disease – seems to have assumed greater importance. New strains arise frequently and are named according to their geographic origin.4

TRANSMISSION, SYMPTOMS AND PROGNOSIS

Influenza is transmitted by droplets and aerosol (e.g. coughing, sneezing) but direct surface transmission is also important, for example a door handle with respiratory secretions from an infected person on it. The disease can spread very rapidly, especially in closed communities (care homes and hospitals for example) and people are typically infectious for about a week, perhaps slightly longer in children.4 In immunocompromised individuals, viral shedding has been observed for up to two weeks.4

The range of symptoms is extremely wide and may include coughing, sneezing, runny nose, headache, fever, muscular weakness, fatigue, and chills. It is now relatively well understood that these symptoms are the result of cytokines and chemokines produced by influenza-infected cells as part of a pro-inflammatory response.6,7 It is also noted that the virus can also cause tissue damage, which can exacerbate the issues caused by the inflammatory response.

For individuals in good health, recovery usually occurs between three to ten days, though influenza is a debilitating disease with people usually requiring bed rest: contrast this with a ‘bad cold’. However, rare complications can occur, such as secondary bacterial pneumonia and very rarely meningitis, viral pneumonia, myocarditis, pericarditis and Reye’s syndrome (the latter primarily in children infected with influenza B).

CLINICAL RISK (AT-RISK) GROUPS

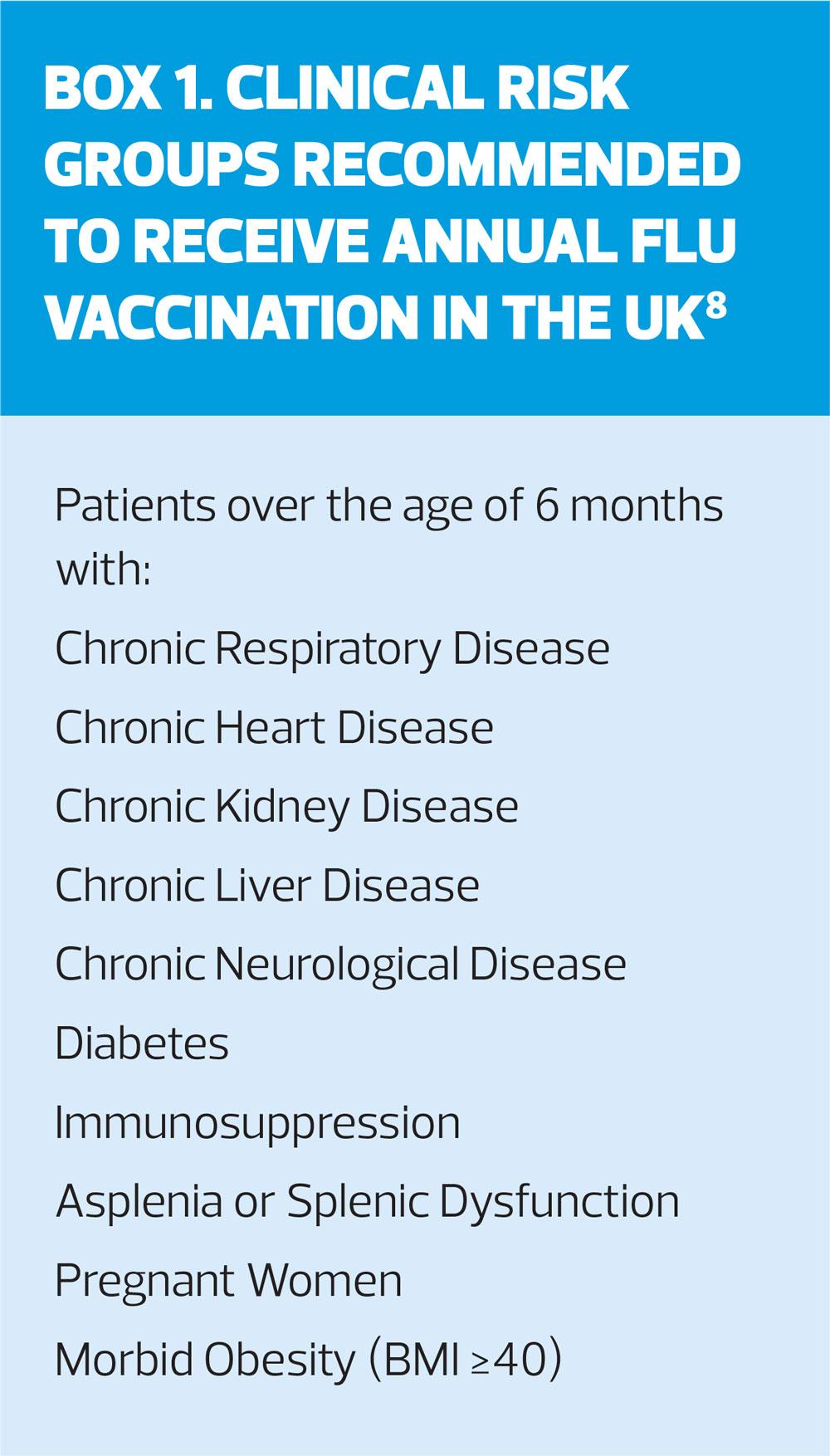

People who fall into one or more of these groups (Box 1)8 can suffer exacerbations of the symptoms listed above, the underlying reason being that such individuals will likely have a degree of immuno-incompetence. Influenza vaccination was originally introduced to some of these groups in the 1960s as they were found to be at higher risk of influenza-associated morbidity and mortality. Subsequent programme modifications added those above 65 years of age (in 2000), pregnant women (in 2010) and the morbidly obese (BMI≥40kg/m2) (in 2014): groups for inclusion to ‘at-risk’ are reviewed annually by the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI).

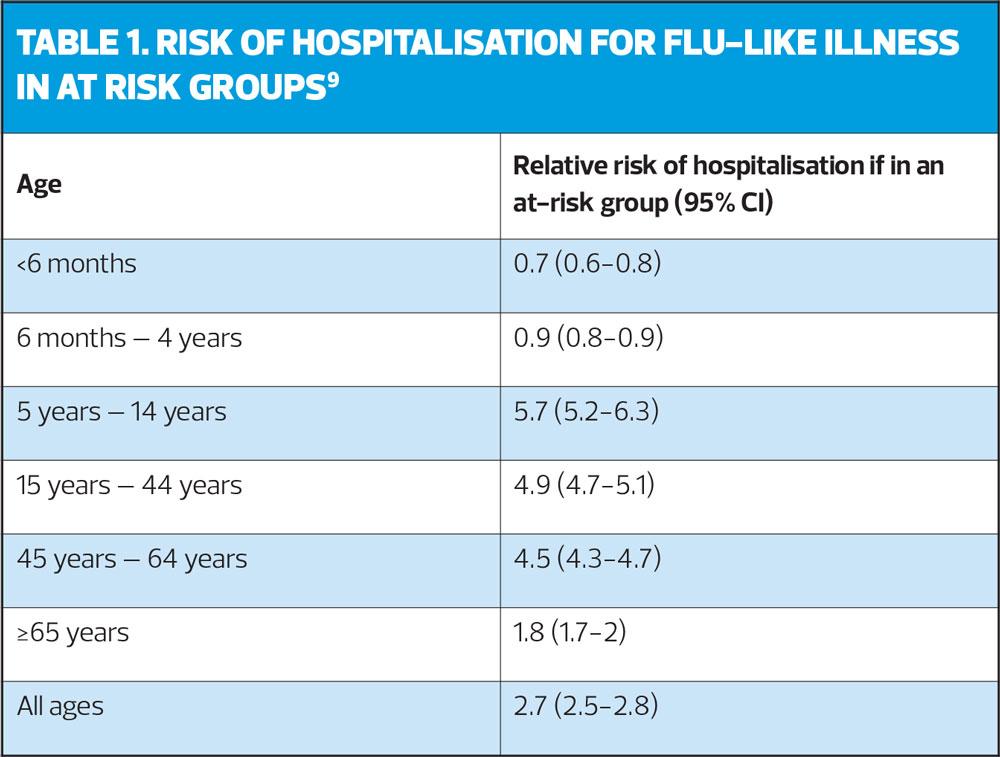

An analysis designed to inform vaccine policy estimates the relative risk (the ratio of the probability of at risk individuals being hospitalised due to influenza-like illness (ILI) compared with the population not in an at-risk group) of influenza-attributable hospitalisation for at-risk individuals to be 2.7 (all ages).9 In this study, flu accounted for about 10% of hospital admissions and deaths attributable to respiratory diseases, and the presence of co-morbidities increased the admission rate five-fold for 5-14 year-olds, to just under two-fold in the 65-plus age group. The case fatality rate was substantially higher in children in at-risk than non-risk groups (Table 1).9

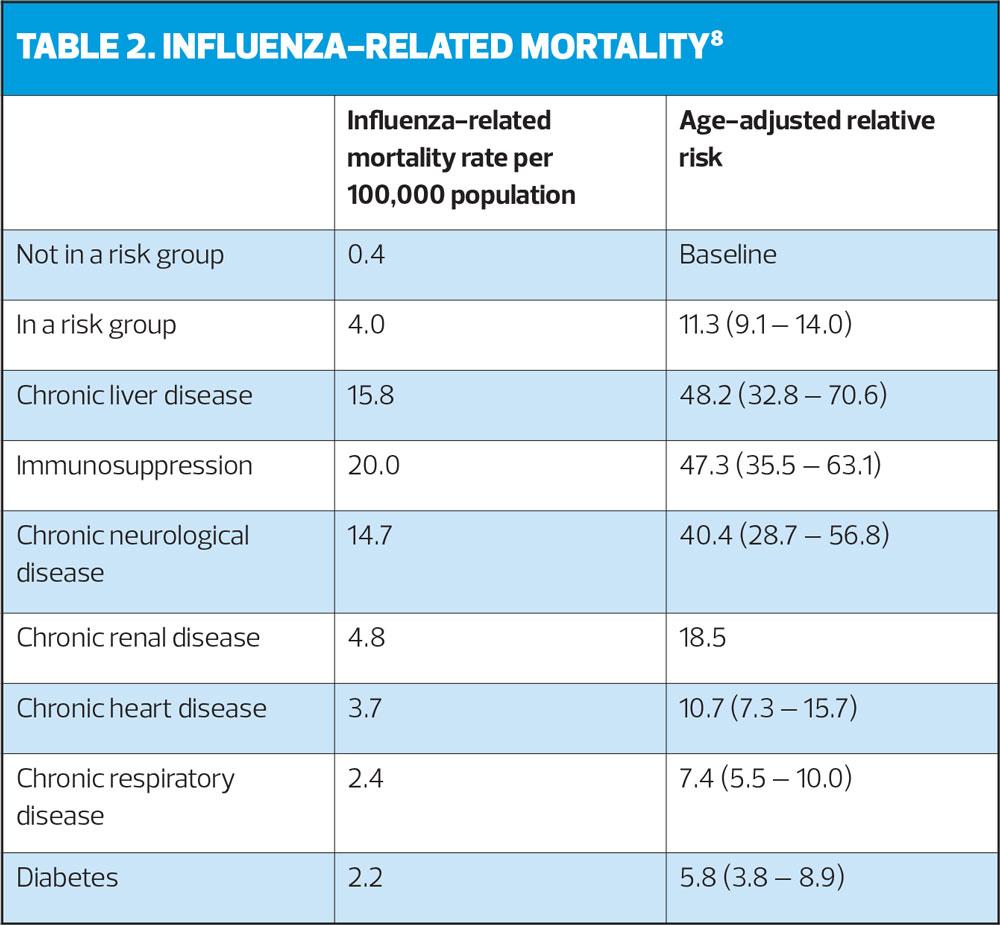

Further evidence highlighting the potential issues facing at-risk individuals is shown in Table 2, which shows influenza-related mortality rates (September 2010-May 2011 data). The last major flu outbreak was in 2009-10, when – although there were only 500 laboratory-confirmed deaths, mortality rates were highest in those with chronic neurological disease, respiratory disease and immunosuppression. People with morbid obesity (BMI>40) were also at higher risk of hospitalisation and/or death).8

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION

Treatment of influenza is mainly symptomatic relief, with bed rest, but Public Health England (PHE) gives comprehensive guidance on when to use antiviral agents in influenza,10 and NICE has issued guidance on post-exposure prophylaxis in people in at-risk groups.11 However, the mainstay against influenza is vaccination.1,4

Currently, the UK programme targets people in at-risk groups, individuals aged 65 years and over and children (children aged two years to ten years receive a live, attenuated intra-nasal vaccine; those at risk aged six months to two years receive an injectable quadrivalent inactivated vaccine).

VACCINATION UPTAKE

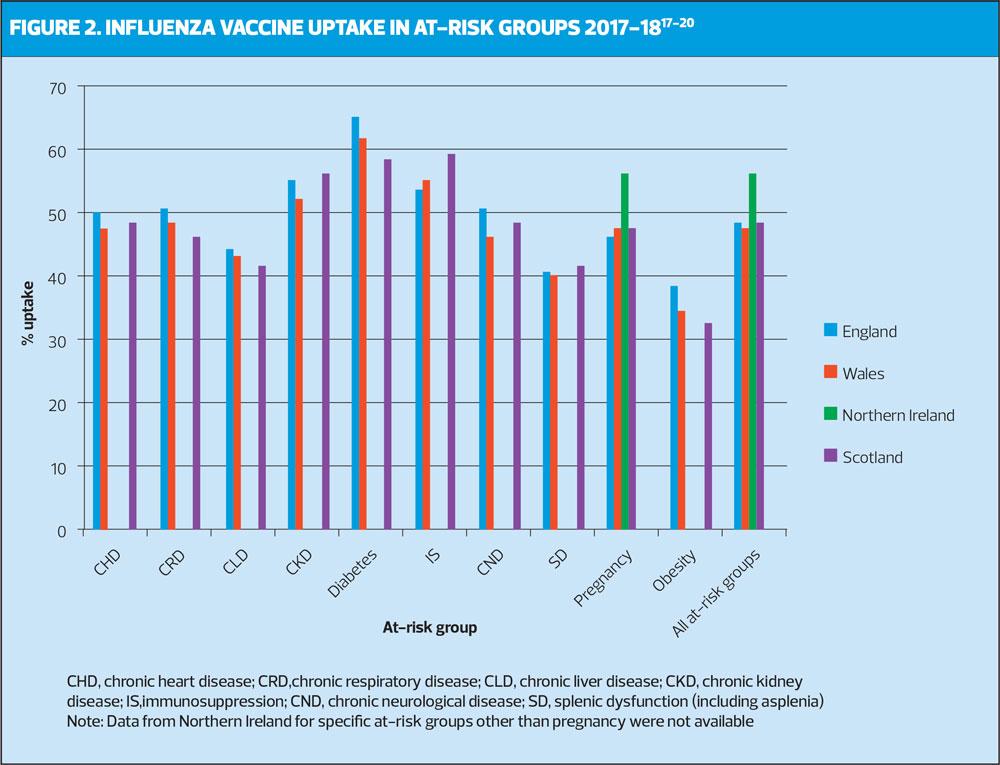

The main focus of this article is influenza vaccination uptake in at-risk groups. Data for the UK flu seasons 2017-2018 is shown in Figure 2. This level of uptake has remained at much the same level for a number of years.

However, influenza vaccination uptake has been below target for almost all at-risk groups throughout the UK: that said, although being below target, the influenza vaccination uptake rates in the clinical at-risk groups are still among the highest in European countries, where none of the European Union member states reporting influenza vaccination coverage could demonstrate that they reach the EU target of 75%.12

For instance, influenza vaccination uptake in the chronic heart disease, chronic respiratory disease, chronic liver disease, chronic neurological disease and asplenia or dysfunction of the spleen at-risk groups has been <50% since 2015-2016 in England and Wales.

In contrast, patients with diabetes had the highest influenza vaccination uptake in England and Wales (second highest in Scotland) – although still below 65%. This higher uptake when compared to other at-risk groups can be attributed to the fact that this patient group has well-defined inclusion criteria leading to better identification in practice registers. For some clinical at-risk groups, there may be a lack of patient education materials explaining the risks of influenza infection associated with their disease.

The relative risk of hospitalisation attributable to influenza is higher for individuals in an at-risk group;9 therefore it is paramount to maintain a high influenza vaccination uptake in these groups.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPROVEMENT

There is limited evidence about how to increase influenza vaccination uptake effectively among most eligible groups but NICE guidance from 2018 recommends a combination of interventions to encourage influenza vaccination:13

- Raise healthcare professional and patient awareness of the benefits of vaccination

- Increase vaccination opportunity

- Collaborate with other agencies

- Have a lead member of staff responsible for the vaccination campain

- Offer extended vaccination clinic times, outreach and mobile services

- Use social media and personalise the vaccination message for the recipient (e.g. link to their pregnancy or risk factors).13

Opportunistic vaccinations could also be considered for patients attending for routine appointments or long term condition reviews or patients requiring frequent check-ups.13

There is a need to better understand the roots of low uptake figures is needed at all levels: geographically (between countries and between regions) but also between different at-risk groups.

We know that there is an inverse association between deprivation and uptake of routine childhood vaccines,14 therefore looking at association between deprived areas and influenza vaccination uptake in the at-risk population is important. For instance, a 2018 study has shown that higher rates of influenza-associated illness hospitalisations and lower vaccine uptake were seen in the most socioeconomically deprived populations of Merseyside.15 Therefore, conducting targeted campaigns to increase vaccination uptake rates in these deprived areas may be of benefit. It has been shown that general vaccine uptake in urban, ethnically diverse, deprived populations could be improved by a locally-designed multi-component approach (e.g. letters, email, SMS texts)16 – this could be applied to influenza vaccination campaigns. Finally disease-specific materials presenting the risks associated with influenza and published data on the benefits of vaccination could be tailored and disseminated at the HCP and patient level – there is a wealth of material available on the PHE website for use by practice nurses, including, for example posters for waiting rooms/treatment rooms.

Where vaccination is offered in secondary care settings to at-risk individuals, for example patients with chronic liver disease or pregnant women, or when it is provided in pharmacies, it is key that this is communicated to the patient’s general practice.

CONCLUSION

For those most at risk from flu, vaccine uptake targets for the coming flu season are the same as previous years (at least 55% in all clinical risk groups) but the long term ambition is to achieve a minimum 75% uptake.1 As we have seen, uptake falls some way below this target but overall, the flu vaccination programme saves thousands of lives every year, as well as reducing consultations in general practice, hospital admissions and pressure on A&E.1

Declaration of interest

The authors are members of the field-based medical team at Sanofi Pasteur, which manufactures influenza vaccine.

REFERENCES

1. NHS England. Annual flu letter, March 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/annual-national-flu-programme-2019-to-2020-1.pdf

2. WHO influenza fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal)

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Types of influenza viruses, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/types.htm

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (The Pink Book). 13th ed. 2015; Chapter 12 – Influenza. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/flu.html

5. van de Sandt CE, Bodewes R, Rimmelzwaan GF, de Vries RD. Influenza B viruses: not to be discounted. Future Microbiol 2015;10(9):1447-65

6. Bradbury J, Cytokines responsible for influenza symptoms identified. The Lancet 1998; 351(9100):421 https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0140-6736%2805%2978362-8

7. Bian J-R, Nie W, Zanf Y-S, et al. Clinical aspects and cytokine response in adults with seasonal influenza infection. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014;7(12):5593-5602 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4307525/

8. Public Health England. The Green Book. Chapter 19. Influenza. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/influenza-the-green-book-chapter-19

9. Cromer D, van Hoek AJ, Jit M, et al. The burden of influenza in England by age and clinical risk group: a statistical analysis to inform vaccine policy. J Infect 2014;68(4):363-371

10. Public Health England. PHE guidance on use of antiviral agents for the treatment and prophylaxis of seasonal influenza, 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/773369/PHE_guidance_antivirals_influenza.pdf

11. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Influenza – seasonal. Scenario: Post-exposure prophylaxis, 2019. https://cks.nice.org.uk/influenza-seasonal#!scenario:1

12. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Seasonal influenza vaccination and antiviral use in EU/EEA member states – Technical report – 18 December 2018. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/seasonal-influenza-vaccination-antiviral-use-eu-eea-member-states

13. NICE NG103. Flu vaccination: increasing uptake, August 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng103

14. Green HK , Andrews N , Letley L , et al . Phased introduction of a universal childhood influenza vaccination programme in England: population-level factors predicting variation in national uptake during the first year, 2013/14. Vaccine 2015;33:2620–8.doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.049

15. Hungerford D, Ibarz-Pavon A, Cleary P, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalisation, vaccine uptake and socioeconomic deprivation in an English city region: an ecological study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e023275. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023275

16. Crocker-Buque T, Edelstein M, Mounier-Jack S. Interventions to reduce inequalities in vaccine uptake in children and adolescents <19 years: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017;71(1)87-97. doi:10.1136/jech-2016-207572

17. Public Health England. Vaccine uptake guidance and the latest coverage data. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/vaccine-uptake#seasonal-flu-vaccine-uptake:-figures

18. HSC Public Health Agency. Influenza (flu) surveillance (Northern Ireland). https://www.publichealth.hscni.net/directorate-public-health/health-protection/seasonal-influenza

19. Public Health Wales. Annual influenza surveillance and influenza vaccination uptake reports: 2003-2019. http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/page.cfm?orgid=457&pid=55714

20. Health Protection Scotland. Influenza: Seasonal influenza vaccine update data visualisation. https://www.hps.scot.nhs.uk/a-to-z-of-topics/influenza/

Related articles

View all Articles