Shingles: prevention and management

Mandy Galloway

Mandy Galloway

Editor, Practice Nurse and medical writer

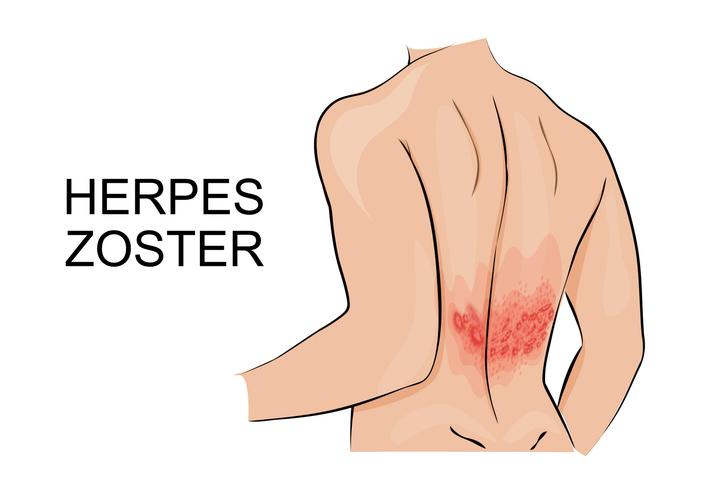

Herpes zoster – shingles – is a painful and debilitating condition but vaccination is clinically and economically effective in its prevention in older patients who are most at risk from infection and complications

The national shingles immunisation programme has been in place for three years now, but so far, less than half of eligible patients between the ages of 70 and 79 have been vaccinated.1 This means that more than half of elderly patients remain vulnerable to shingles infection, which causes debilitating illness, and can result in long lasting, difficult to treat neuropathic pain, and even – in one in 1,000 – death.2

Shingles (herpes zoster) is caused by reactivation of a latent varicella zoster virus (VZV), often decades after the primary infection that causes chickenpox, usually in childhood. As 90% of the adult population have been exposed to chickenpox, they are at risk of developing shingles in later life.3

VZV remains dormant in the sensory dorsal root ganglia, where it establishes a permanent latent infection, which is kept in check by the immune system. However, reduced immunity as we grow older (immune senescence) or immunosuppression can cause the virus to be reactivated, flaring up in a single area of skin (dermatome).

The most usual site of reactivation is the thoracic nerves, followed by the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (ophthalmic shingles).3

The first signs of shingles begin most commonly with abnormal skin sensations and pain in the affected dermatome. In the prodromal phase, headache, photophobia, malaise and sometimes, fever, may develop before the appearance of a vesicular rash: this is always unilateral, i.e. affecting only one side of the body or face. Any rash that crosses the midline is not shingles! Prior to the appearance of the rash, diagnosis is difficult.

The affected area may be intensely painful and itchy, and may be associated with tingling or numbness. Typically, the rash phase will last between two and four weeks.

In immunocompromised patients, the rash may affect several dermatomes.

More than 50,000 cases of shingles occur in people over the age of 70 each year.2 Of these, 1,400 are so severe that they result in hospital admission.4 It is estimated that in people aged 70 years and over, around one in 1,000 cases results in death.2

The severity of shingles increases with age, and can lead to post herpetic neuralgia (PHN) – defined as severe and persistent pain that lasts for at least 90 days after the onset of the rash. (Table 1) PHN lasts, on average, from three to six months – but can last longer. The severity of pain can vary and may be constant, intermittent or triggered by stimulation of the affected area.

PREVENTION

The UK was the first country in Europe to provide free shingles vaccination as part of a national immunisation programme, following a comprehensive assessment by the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation of its health and economic benefits.

From 1 September 2016, shingles immunisation should be offered to:

- Patients aged 70 years on 1 September 2016

- Patients aged 78 years on 1 September 2016.

In addition, patients who were eligible for immunisation in the first three years of the programme, but who have not been vaccinated against shingles remain eligible until their 80th birthday. These are individuals:

- Aged 71 to 73 on 1 September 2016

- Aged 79 on 1 September 16

The reason for the cut off at age 80 is because the efficacy of the vaccine reduces with the recipient’s increasing age, meaning it is neither clinically nor economically effective to offer the vaccine to those over the age of 80.

GP practices are urged to use every opportunity to offer shingles vaccination to eligible patients to help to protect as many elderly people as possible from this painful and debilitating condition. The shingles vaccine can be administered at the same time as the seasonal flu vaccine, (by separate injections at different sites) so this is an ideal opportunity to maximise the percentage of patients who are immunised.

Implementation of the shingles immunisation programme has been successful overall but regional discrepancies still remain.5 By the end of March 2016, just under half of eligible 70 and 78 year olds had been vaccinated against shingles.1 However, uptake is varied across England, from 39.1% in Essex to 51.6% in Cheshire, Warrington and Wirral for the routine 70 year old cohort, and from 38.6% in Essex to 50.5% in Cheshire, Warrington and Wirral for the 78 year old catch-up cohort.5

The Department of Health has announced that Sanofi Pasteur MSD’s shingles vaccine, Zostavax, will continue to be used in the national shingles immunisation programme for at least the next two years. This decision follows a thorough and detailed evaluation of the vaccine’s clinical and cost effectiveness as part of a rigorous tender process.

Zostavax is a live attenuated vaccine, and so should not be given to:

- People with primary or acquired immunodeficiency states, including acute and chronic leukaemias, lymphoma; immunosuppression due to HIV/AIDS; those who have received a solid organ transplant and are on immunosuppressive therapy; or stem cell transplant in the past 24 months.

- People who are receiving immunosuppressive or immunomodulating therapy, including short-term high-dose or long term lower dose corticosteroids. Zostavax is not contraindicated for people on topical or inhaled corticosteroids.

- People who are receiving or who have received biologic therapies (e.g. anti-TNF therapy, etanercept, infliximab) in the past 12 months, except on specialist advice.

MANAGEMENT

With more than half of patients aged 70 and over unvaccinated against shingles, it is likely that many will develop the condition. The lifetime risk of developing shingles is estimated at one in four.

Diagnosis is usually based on the presence of typical lesions on a single dermatome. In straightforward cases, further investigation is not generally useful as scrapings for smears and cultures are usually negative.3

In a patient with shingles, the advice should be to keep the rash clean and dry to reduce the risk of secondary bacterial infection. Calamine lotion can be used to help alleviate itching. Topical antiviral treatment is not recommended, although topical antibiotic treatment may be needed if a secondary bacterial infection develops.

The antiviral drug, aciclovir, reduces the severity and duration of shingles, but has not been shown to prevent PHN.

The related drugs, valaciclovir and famciclovir have been found to reduce the risk of HZV pain, but there is little evidence that they prevent PHN.

Oral antiviral drugs are most effective if they are initiated within 72 hours of the onset of the rash, but can be started up to one week after the rash develops, especially in those at higher risk of severe disease.

Antiviral agents should be offered to:

- Anyone over the age of 50 years

- People of any age with non-truncal involvement (neck, limbs, perineum)

- Patients with moderate or severe pain or rash

- People with ophthalmic involvement

- People who are immunocompromised3

Antiviral treatment regimens8

- Aciclovir: 800 mg, five times a day for 7 days at 4-hourly intervals (omit the night time dose)

- Valaciclovir: 1000 mg three times a day for 7 days

- Famciclovir: 500 mg three time a day or 750 mg 1-2 times a day for 7 days

Aciclovir is much cheaper than other antivirals, but the dosing schedule is more onerous. Valaciclovir and famciclovir are more effective at reducing pain than aciclovir, have greater levels of antiviral activity and have a more convenient dosing schedule, but are considerably more expensive.8 Antiviral drugs should be prescribed with caution in people with renal impairment. Refer to the summary of product characteristics for each drug for recommended dose reductions.

Adverse effects

Aciclovir is generally well tolerated, but may cause gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain. Skin rashes, photosensitivity and urticaria are also common.

The most common adverse effects for valaciclovir and famciclovir are headache and dizziness, GI effects and skin disorders such as rashes, photosensitivity and itching. Abnormal liver function tests have also been reported with famciclovir.8

Oral corticosteroids may be helpful in reducing the inflammation that contributes to acute pain in shingles, and may improve the appearance of the rash, but are associated with significant risk of adverse events, especially in older patients.8 If used, they must always be prescribed with antiviral agents as they suppress the immune system.3

Analgesia for shingles-associated pain is likely to be required, and the first line agents will be paracetamol plus or minus a weak opioid, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. However, these agents are often ineffective for PHN. Neuropathic pain is treated with greater success with tricyclic antidepressants and anti-epileptic drugs such as gabapentin and pregabalin. There is also limited evidence to suggest that early treatment (in the acute phase of shingles) may reduce the risk of developing PHN.8

Topical lidocaine is also licensed for PHN but should not be used on areas of skin still affected by the rash. For more information, see Shingles and neuropathic pain, by Dr Mary Lowth (Practice Nurse, December 2013)

WHEN TO REFER

Patients with ophthalmic shingles – 10 to 20% of cases – need to be seen by a specialist immediately (within 24 hours) as it poses a threat to sight, and may require inpatient treatment. The typical sign of ophthalmic shingles is a rash on the side and tip of the nose (Hutchinsons’s sign). An unexplained red eye in a patient with shingles may also be an indication of ocular involvement.

You should also refer patients who are immunodeficient, for whatever reason, to a specialist in infectious diseases.

People with severe infection, involving more than one dermatome, or with recurrent disease should also be seen in secondary care.

Complications of shingles, other than PHN, may include disseminated zoster, where the rash spreads over a large part of the body and can affect the heart, lungs, liver, pancreas, joints and gastrointestinal tract; cranial nerve complications such as Ramsay Hunt syndrome (pain in the ear, rash around the ear, mouth, face, neck and/or scalp, and loss of movement in facial nerves; and bacterial infection of the skin: any of these complications warrant specialist involvement.

Although this article has focused on shingles in the older person, it can also occur in younger people, including pregnant women. While it is generally a less serious illness in young people, it is important to seek specialist advice for shingles in pregnancy: unlike chickenpox, it is unlikely to cause harm to the unborn baby, but antiviral treatment should not be prescribed other than on the recommendation of a specialist as it is essential to balance the benefits of treatment against the possible risk of adverse effects on the fetus.

CONCLUSION

Shingles can be a horrible illness in elderly people and, as in most infectious diseases, prevention is better than cure. The vaccine has been shown to be effective in reducing the risk of shingles in people aged 70 to 80 years, and practice nurses should encourage their patients to take up the offer of vaccination.

REFERENCES

1. Public Health England. Shingles vaccine coverage report, England, September 2015 to February 2016, 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/521577/hpr1616_shngls-VC.pdf

2. Public Health England. Immunisation against infectious diseases – the Green Book. Shingles (herpes zoster). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/shingles-herpes-zoster-the-green-book-chapter-28a

3. PatientPlus. Shingles and shingles vaccination. http://patient.info/doctor/shingles-and-shingles-vaccination

4. Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. Statement on varicella and herpes zoster vaccines, 2010. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http:/www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@ab/documents/digitalasset/dh_133599.pdf

5. Public Health England. Herpes zoster (shingles) immunisation programme 2014/2015: Report for England. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/480254/Shingles_annual_14.15.pdf

6. NHS England and Public Health England. Shingles immunisation programme from 1 September 2016 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/533325/Shingles_Letter_June16.pdf

7. Public Health England. Vaccination against shingles: 2015/16 - Information for healthcare professionals, 2016 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/503099/PHE_Shingles_advice_for_health_professionals_2015-16__February2016_V4.pdf

8. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Shingles. Scenario: Management, 2013. http://cks.nice.org.uk/shingles#!scenario:1

Related articles

View all Articles