COVID-19, fake news and the role of the general practice nurse

RHIAN LAST

RHIAN LAST

Nurse Educator

Associate, Experience Led Care Programme

RCGP Yorkshire Faculty Board Member

Self Care Forum Board Member

Social media and online sources are rife with misinformation and disinformation, never more so than now. This article will explore the issues surrounding fake news and COVID-19, consider them in relation to the role of the general practice nurse (GPN) and discuss solutions

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has without doubt caused immense global disruption. As a result of strict distancing impositions there is a heavy reliance on digital resources to network, connect and keep in touch. Whilst these are proving valuable there are ways that social media is impacting negatively during this pandemic.1

In the few months since the initial cases of COVID-19 there has been a significant amount of confusing and incorrect information shared over both traditional and social media. The World Health Organization has referred to an ‘infodemic’ of misinformation, disinformation and rumours all of which presents huge barriers when seeking to identify dependable sources of information.2 Misinformation involves inaccuracy and errors whereas disinformation refers to purposefully created falsehoods, which are then spread with malicious intent. Both gain traction when people are seeking solutions, in this case to the pandemic situation, and then unwittingly contribute to the spread of inaccurate information.3

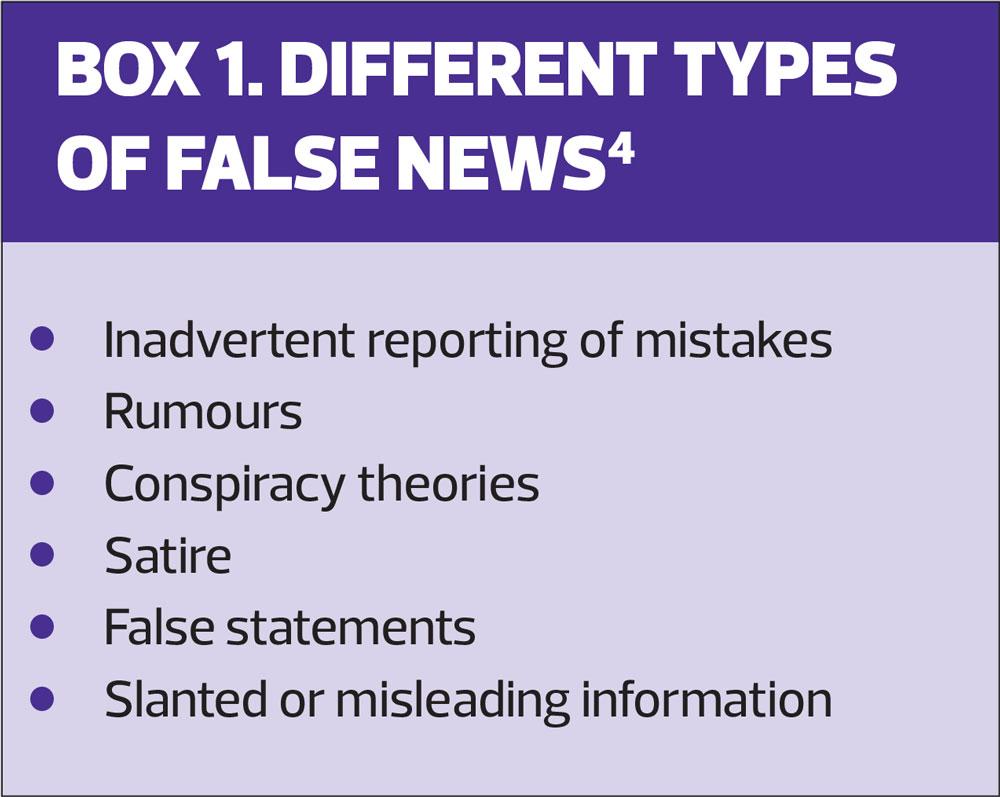

In relation to COVID-19 the different types of false news are all playing out. While the situation is evolving so rapidly, scientists are continually learning and re-adjusting the data and knowledge base. This creates an arena where mistakes can inadvertently be reported, and data extraction and presentation can sometimes be incorrect: for example, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) was obliged to publish a retraction and correction after an unintentional upload error resulted in incorrect ranges for predicted cumulative deaths in Europe.5

Rumours continually abound, for example, about potential treatments for COVID-19, when the UK lockdown could end and also how the UK lockdown might end. As the situation is evolving so are the rumours.

There have been many conspiracy theories around COVID-19, the most notable being that the virus is related to the roll out of 5G networks and also that the virus originated in a laboratory and may have been man-made.

US President Donald Trump recently made a statement positing the value of ingestion or injection of disinfectants to treat coronavirus. Later he sought to clarify that the statement had been made with sarcasm (satire), though unfortunately there is alarming evidence that some people have since acted on his original statement, putting their lives at risk as a consequence: in the 18 hours following Trump’s comments, calls to the New York Poison Center about disinfectant exposure more than doubled to 30, from 13 in the same period 12 months ago.6 Incidentally, Trump then denied any responsibility for these incidents.

False information surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic causes worry and distress. A typical example would be photos of crowded beaches and cities that were circulated on social media creating concern that there would be an ensuing surge in new COVID-19 cases. The photos were purported to have been taken during the lockdown but were in fact historic rather than current.

Again, there is evidence of slanted or misleading information being currently shared: for instance, there has been misleading advice that vodka can be effectively used as a hand sanitiser when in fact to kill the virus effectively, the alcohol by volume (ABV) needs to be ≥60%, whereas the typical ABV of vodka is 37.5-40%. In another example, until very recently the figures presented in the Department of Health and Social Care’s daily death toll for the UK only represented hospital deaths, giving the impression that the total number was lower than it really was.

IMPACT

Once fake news takes hold and gains momentum it induces fear, anxiety and distrust. People become cynical of institutions and authorities. If fake news gains general acceptance it can then prove very challenging to correct.7

Fake health information messages tend to have an aggressive focus whereas messages that are based on evidence are considerate and cathartic. Where discussion is encouraged this stimulates people to take time to think and consider and this can help to overcome false news.8 Two exemplars (out of many) on Twitter are Professor Trisha Greenhalgh, Professor of Primary Care, University of Oxford (@trishgreenhalgh) and Professor Karol Sikora, oncologist and CMO at Rutherford Hospital (@ProfKarolSikora) who both present even-handed, reliably-sourced information and prompt positive conversation.

Epistemic trespassing is a term used to describe people who feel that they have knowledge and skills that can transfer to a specialised subject where this may not actually be the case.9 These people can become rapid spreaders of unsubstantiated information via social media. To combat this the NHS has joined forces with Google, Twitter, Instagram and Facebook to stem COVID-19 related false news. Twitter, Instagram and Facebook are giving verification through the addition of a ‘blue tick’ to some 800 accounts belonging to NHS organisations and associated reputable individuals. When using social media, look out for these ‘blue ticks’. They are a mark of assurance useful for health care professionals and patients alike.10

IMPLICATIONS FOR GENERAL PRACTICE

An inadvertent consequence of lockdown is that there has been a significant drop in the number of people contacting their GP surgery about other health matters. This may be down to a misconception that GP surgeries are closed for services other than COVID-19. There are also fewer people attending hospital emergency departments. There is a concern that as a result there may be a delay in diagnoses of stroke, cancers and cardiovascular events. Consequently, there is currently widespread national promotion via mainstream and social media to get the message out there that GP services are available and, while you may have a telephone appointment or an online consultation with your GP or GPN, rather than actually having to go in to the surgery, it is vital that if you have a health problem or concern you get in touch without delay to have this investigated. GPNs can help spread these messages.

SOLUTIONS TO ADDRESS FAKE NEWS

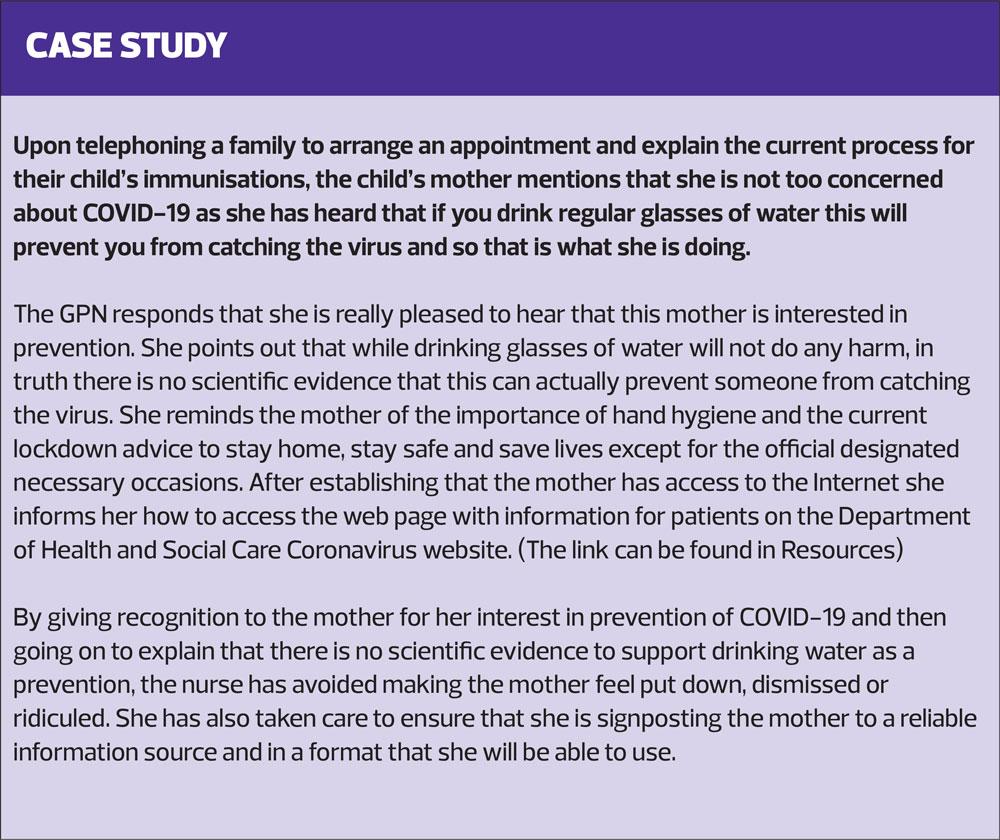

Primary care is rising admirably to the challenge of coping with COVID-19 while also addressing usual general practice services. Although there is some variation around the country, many GPNs are maintaining services such as childhood immunisations, some cervical cytology, and some dressings, arranging appointments as much as possible via the telephone, giving patients the opportunity to ask questions and to address any concerns they may have about attending the surgery. This will help to ensure that any face-to-face time is minimal, efficient and succinct.

This is also a time of opportunity, where healthcare professionals are actually increasing use of alternatives to face-to-face clinics through video consultations (Activity 2).

All these interactions are useful opportunities to identify any COVID-19 related misconceptions and to signpost people to reliable sources of information. Research has identified that nurses are the most trusted profession.11 This means you are ideally placed to listen to your patients in order to understand their knowledge and perceptions and then steer them accordingly.

SUMMARY

Fake news can cause fear, anxiety and distrust. Once this takes hold it can be very difficult to undo. This is having a negative impact and compounding the already very difficult challenges posed by the global COVID-19 pandemic.

GPNs are held in a position of high trust. They can help their patients identify, and also avoid, fake news and source information that is reliable, appropriate and useful.

REFERENCES

1. Limaye RJ, Sauer M, et al. Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digital Health 2020; ePub April 21, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30084-4

2. Garrett L. COVID-19: the medium is the message. Lancet 2020; 395: 942–43.

3. Pulido C, Ruiz-Eugenio L, Redondo-Sama G, Villarejo-Carballido B. A new application of social impact in social media for overcoming fake news in health. Int J Environment Res Public Health 2020;17(7): 2430.

4. Merchant RM, Volpp KG, Asch DA. Learning by Listening—Improving health care in the era of Yelp. JAMA 2016;316:2483–4.

5. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Correction in Uncertainty Intervals for Cumulative COVID-19 Death Forecasts in Europe: http://www.healthdata.org/news-release/correction-uncertainty-intervals-cumulative-covid-19-death-forecasts-europe

6. Calls to poison centers spike after President’s comments about using disinfectants to treat Coronavirus; 25 April 2020.

7. Wang, Y, McKee, M, Torbica, A, Stuckler, D. Systematic literature review on the spread of health-related misinformation on social media. Soc Sci Med 2019;240:112552.

8. Pulido CM, Ruiz-Eugenio L, Redondo-Sama G, Villarejo-Carballido B. A new application of social impact in social media for overcoming fake news in health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2430. Published 2020 Apr 3. doi:10.3390/ijerph17072430

9. Barnett SM, Ceci SJ. When and where do we apply what we learn? A taxonomy for far transfer. Psychological Bulletin 2002;128:612-637. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.612

10. NHS Take Action Against Coronavirus Fake News Online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2020/03/nhs-takes-action-against-coronavirus-fake-news-online/

11. Ipsos Mori. Trust In Professions; 2019

Related articles

View all Articles