Varicella vaccination – why now?

Chantelle Walker, QN, GPN, RGN. Lecturer for Fundamentals of General Practice & Discovering a Career in General Practice, Birmingham City University

Practice Nurse 2025;55(6):10-14

For the first time, varicella vaccination will become part of the routine childhood immunisation schedule – but is it really necessary? We look at the compelling reasons for protecting children from this common childhood disease

In January 2026 we will see another update to the childhood immunisation schedule. As general practice nurses (GPNs) we are very familiar with the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and unfortunately, issues with uptake, but less familiar with the varicella vaccine. Although the first vaccination for varicella was discovered 50 years ago,1 many countries across the globe, including the UK, have continued to allow chickenpox to spread freely, treating it as only a mild disease. In November 2023, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) published its recommendation for varicella vaccination to be introduced into the UK immunisation schedule. It recommended that the universal vaccination programme should combine MMR and Varicella to become MMRV and be offered to all children at both 12 and 18-month routine immunisation appointments.2

Varicella, more commonly known as chickenpox, is a disease many of us are familiar with. It is caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and often causes relatively minor symptoms in children, which can be managed at home. However, some people, including adults, pregnant women, immunosuppressed patients and neonates, are at higher risk of complications,3 including secondary bacterial infection, pneumonia, bacterial encephalitis, hepatitis and mortality.4 Even healthy children and adults can go on to develop complications from chickenpox, with skin infections such as cellulitis being the most common cause of hospitalisation.5 This can result in significant stress and anxiety for both patients and carers, especially when occurring in younger patients. Recent research also reveals that varicella infection has a much more significant impact on patients’ health-related quality of life than previously thought.6

If we look at individual case studies of severe varicella, the impact of complications from the disease becomes clear, particularly when considering the mortality seen in both adults and children. In 2009, Angie Bunce-Mason’s 3-year-old daughter, Elana, developed pneumonia after catching chickenpox. Following emergency admission to hospital, Elana suffered a cardiac arrest and died the following day. She had been a healthy child, with no significant medical history or immunosuppression. Angie described the impact as ‘horrendous,’ saying that family life has never been the same since.7 After more than 16 years of campaigning, Elana’s family recently celebrated the addition of the varicella vaccine to the routine childhood immunisation schedule.8 The preventable nature of Elana’s death, and others like hers, through an established, evidence-based vaccination programme, underscores the tragedy of each of these individual losses.

So why is the UK introducing varicella vaccination now? Several factors have informed the JCVI’s recommendation and the UK Government’s subsequent decision, including the cost-effectiveness of introducing a universal vaccination programme and new research re-evaluating the impact of chickenpox vaccination on shingles incidence in adults.

With many cases of chickenpox seen as self-limiting only, the financial burden on the NHS has been considered to be quite low. However, it can be argued that the full extent of the impact on health services isn’t fully known, due to many hospitalisations being documented as the complication of the disease such as pneumonia, for example, rather than varicella itself. Globally, it is believed that varicella-related healthcare incidents have a significant impact on primary healthcare, and are are costly to public services.9 Indirect costs of chickenpox, including factors such as lost workdays due to associated childcare needs, which have been estimated to be between £20 and £70 million annually, are also a significant consideration.10

Across the globe, more than 40 countries have introduced a vaccination programme and seen a significant impact on healthcare services. In the US, after 25 years of delivering a vaccine against chickenpox, hospitalisations were down 94% and deaths relating to complications from varicella reduced by 97%.11 These figures provide evidence of a material reduction in preventable suffering.

VARICELLA IN PREGNANCY

Increased herd immunity also protects more vulnerable members of the population from chickenpox. As previously mentioned, pregnant women, immunocompromised patients and newborn infants are at higher risk of complications from varicella infection, with many of these groups often requiring urgent, same-day specialist advice.9 These risks are considered so high that around ten years ago the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommended that varicella vaccination should be considered for women who are seronegative for varicella IgG (i.e., have no antibodies to varicella in their bloodstream),12 although, as the vaccination is live, it can only be administered prior to pregnancy or postpartum. Although screening for varicella in pregnancy isn’t currently recommended in the UK, if a pregnant woman presents with recent exposure to chickenpox and has no history of VZV in any form and no prior varicella vaccination, it is recommended that antibody testing is undertaken, prior to administering post-exposure prophylaxis treatment.13 The complex and lengthy nature of managing these exposures, the impact on healthcare services and the stress this causes for pregnant women is itself a rationale for introducing the vaccine.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SHINGLES?

A major concern when considering the introduction of the varicella vaccine has been its potential effect on shingles, particularly the possibility of increasing disease incidence. It was previously thought that occasional re-exposure to chickenpox, and therefore to the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), could boost the immune system and provide additional protection against shingles in adults. For example, grandparents caring for grandchildren might be exposed to chickenpox, which would stimulate their immune system and boost antibodies against VZV without them becoming unwell. This theory, known as the exogenous boosting hypothesis,14 was one of the factors that influenced the JCVI’s 2009 decision not to recommend introducing a routine varicella vaccination programme in the UK.15

Following the primary chickenpox infection, the VZV establishes latent infection within the dorsal route ganglia nerves, and later in life, often when the immune system is suppressed or as we age, this virus reactivates and presents as shingles.16 Like chickenpox, shingles is often associated with a rash, with other presenting symptoms including general malaise, fever, headache and pain and sensitivity at the rash site. Rashes can occur anywhere on the body, but most commonly appear as a unilateral band across the torso, though they can also affect the face and eyes. Approximately 1 in 9 adults in the UK will develop shingles in their lifetime,17 with just under 1% developing the condition each year and 10-20% of those aged over 50 going on to develop long-term post-herpetic neuralgia.18 In addition to this, in 2022 alone, there were 44 registered deaths linked to shingles.19 For these and other reasons, in 2013 the JCVI introduced a shingles vaccination programme. As practice nurses, we are well-versed in encouraging vaccination against shingles and are aware of the importance of this programme.

As the US has had a robust varicella vaccination programme for more than 25 years, data has now been reviewed and carefully considered by the JCVI. This real-world data has shown that there has not been the expected increase in the incidence of shingles since introduction of the chickenpox vaccine.11 It is thought that the well-established shingles vaccination schedules may contribute to this. The shingles programme has continued to be expanded in the UK, now covering many adults aged 65 and over, and from September this year severely immunosuppressed individuals aged 18 years and over.20

IMPACT ON VACCINATION UPTAKE

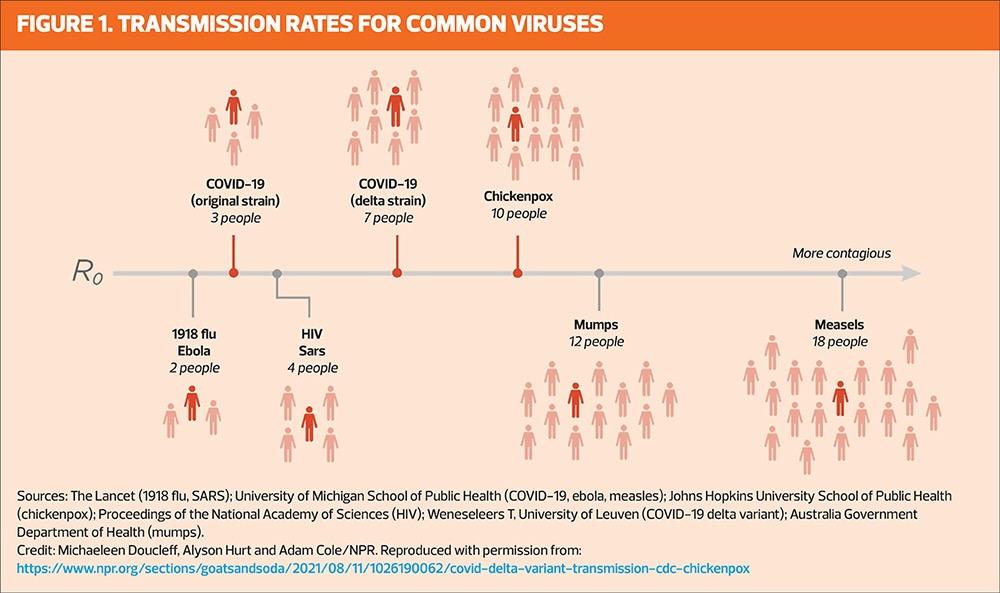

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases known to humans, with one infected person capable of transmitting the virus to a further 12–18 people.21 Because the measles virus is so infectious, a high level of vaccination coverage is needed to achieve herd immunity, with research suggesting a required uptake of 89–95% for two doses of the MMR vaccine.22 The World Health Organization recommends vaccine coverage of 95% worldwide to protect populations and prevent mortality. This is especially relevant considering the recently observed global increase of infections, and subsequent complications and deaths from measles.

In the UK, uptake for two doses of MMR currently sits at 84.5%, more than 10% below the recommended threshold.23 With these figures in mind, we may question whether adding vaccinations to the routine childhood immunisation schedule is a good idea at a time when uptake is already much lower than we would like. However, when questioned, 74% of parents stated they would be very likely to accept an MMRV vaccination, with the majority preferring the option of a combination vaccine rather than an additional immunisation.24 Additionally, other countries which have introduced the varicella vaccination have experienced relatively good uptake. For example, in Germany, vaccine uptake for one dose of the varicella immunisation is above 80%, and subsequently incidence of the disease has significantly reduced across all age groups.25 From a personal perspective, as both a mother to young children and a GPN, I welcome the change. Notably, in the last few years I have seen many parents opting to pay privately to get the varicella vaccine, demonstrating the demand for protection against the disease.

NEW SCHEDULE

The introduction of MMRV into the vaccination programme has been timed to coincide with the introduction of the new 18-month childhood immunisation appointment, but why has a new appointment been added? Boroughs in London consistently rank in the lowest five areas nationally for MMR vaccine coverage, with Hackney only achieving a 60.8% uptake for two doses of MMR.23 To tackle this disparity and manage emerging outbreaks in areas with low vaccine uptake, several London boroughs introduced an additional 18-month appointment to administer the MMR vaccine, earlier than the usual second dose given at 3 years and 4 months. This is supported by WHO, which recommends administering the second MMR dose at 15-18 months to ensure children are protected from an early age, and individuals who are most susceptible to these viruses, and their complications, are kept to a minimum.26,27 Ultimately, this improves overall coverage and reduces the chance of measles outbreaks. Research showed that this intervention improved uptake of the second MMR vaccine and in 2017–2018 uptake increased by an impressive 9.2%, while over a 6-year period, an average increase of 3.3% was observed.28 With these figures in mind, the JCVI and UK Health and Security Agency (UKHSA) consider the likely benefit of increasing overall uptake of two doses of MMR justifies the additional 18-month appointment. There is the additional advantage of having the opportunity to check the child’s vaccine status and offer missed doses as required, at the next 3-year 4-month ‘pre-school’ immunisation visit. Furthermore, evidence indicates that vaccinations scheduled at older ages are associated with lower attendance by parents and carers, resulting in delayed immunisation and increasing the chance of local outbreaks.29 So it makes sense to introduce a new 18-month appointment, which also lends itself well to the suggested varicella vaccination schedule.

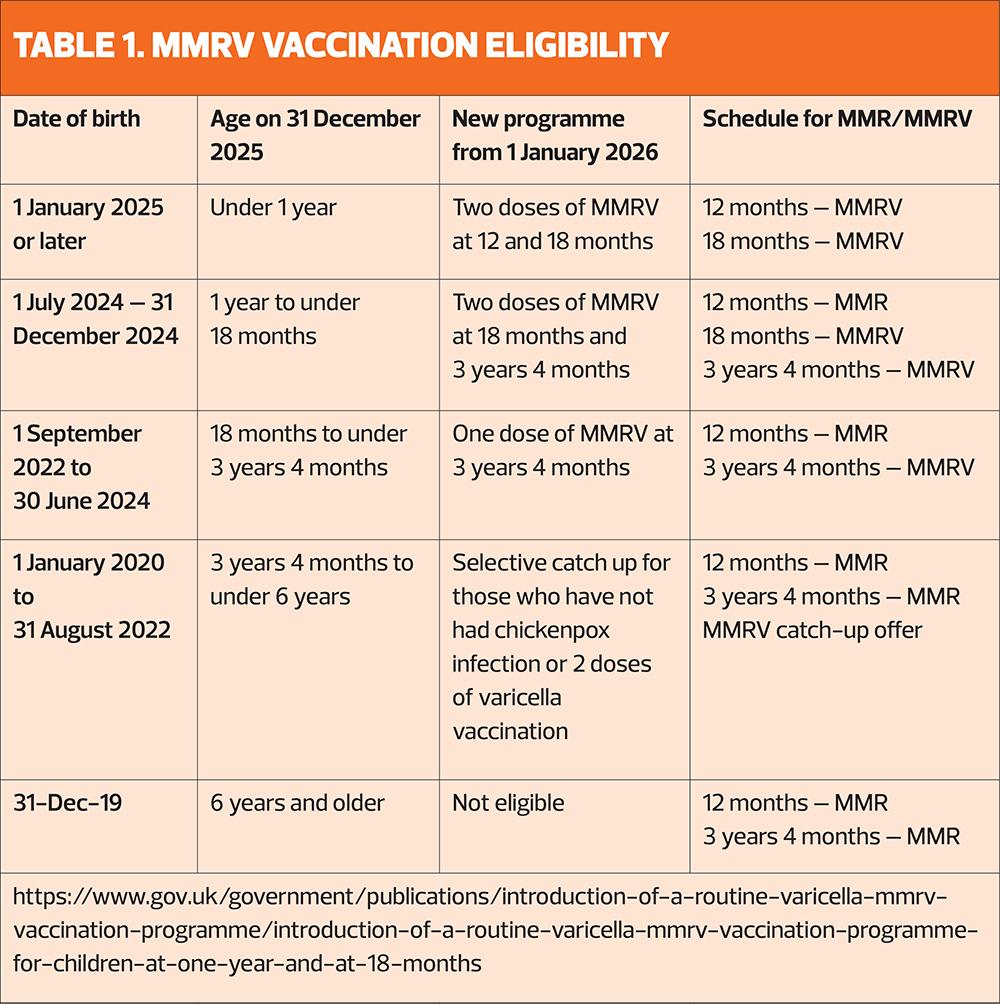

ELIGIBILITY AND CATCH-UP PROGRAMME

From 1 January 2026 all children turning 12 months, i.e. those born on 1 January 2025 and after, will be offered two doses of MMRV. The first will be at their routine one-year appointment and the second at the recently introduced 18-month appointment. The only other group of children who will be offered two doses of MMRV are those born between 1 July 2024 and 31 December 2024. They will be invited at 18-months and 3 years 4 months for their two doses. Those who will have already turned 18 months but not yet had their pre-school immunisations will be offered one dose of MMRV at their 3-year 4-month appointment. There will also be a catch-up programme starting November 2026 for children aged between 3 years and 4 months and 6 years, who haven’t had chickenpox infection or varicella vaccination.

MMRV will be available as Priorix-Tetra (GSK) and ProQuad (MSD), ordered in the usual way via ImmForm. Priorix-Tetra is the preferred option for children who do not accept porcine gelatine.30 From 1 January 2026, the MMR-only vaccine will no longer be used in the routine childhood immunisation programme. It will, however, remain available for older children and adults who require catch-up MMR vaccination but are not eligible for varicella vaccination. GPNs and vaccinators should take every opportunity to ensure patients of all ages are up to date with their MMR immunisations, helping to protect communities and vulnerable patients from future measles outbreaks.

Children born after 1 January 2020 who need to catch up on MMR should have the MMRV vaccination.30 The incomplete immunisation schedule is currently being updated to reflect these changes. Those involved in the vaccinating must ensure they receive training on any new vaccine, and the UKHSA is running a webinar on these changes on 3 December, 14:15–15:00 hours – register at https://www.integratedcaresupport.com/event-details-registration/ukhsa-webinar-upcoming-changes-to-the-routine-childhood-immunisation-schedule (https://www.integratedcaresupport.com/event-details-registration/ukhsa-webinar-upcoming-changes-to-the-routine-childhood-immunisation-schedule).

CONCLUSION

Adding varicella vaccination to the routine childhood schedule marks a significant milestone in protecting children’s health. It spares families the anxiety and heartache that can accompany serious complications and reflects the success of sustained advocacy from clinicians and parents who have long recognised the preventable nature of this disease.

Although GPNs may have concerns about an increased workload, the schedule has been carefully designed to minimise impact, and the catch-up programme is unlikely to be extensive, as many children eligible for an additional dose of MMRV will already have had chickenpox. As GPNs, we are in an ideal position to encourage vaccine uptake and educate patients and carers on the benefits of immunisation.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

- From 1January 2026, varicella will become a part of the routine childhood immunisation schedule, and will be included in the MMR vaccine (MMRV)

- Children will have one dose of MMRV at 12 months, and the second dose at 18 months

- Vaccinators will need to check patients’ date of birth to check eligibility for both routine and catch-up doses

- The introduction of the 18-month appointment aims to increase uptake of vaccinations and to tackle the threat of measles outbreaks in the UK

- Although chickenpox is generally self-limiting, it can cause secondary complications and rarely mortality, even in healthy patients

- Chickenpox is a significant concern for immunosuppressed patients and pregnant women

- A robust vaccination programme is already well established in more than 40 countries across the globe and has shown to significantly reduce complications, hospital admissions and mortality from the disease

- Data from the US after more than 25 years of vaccinating disproves the theory that cases of shingles in adults rise following introduction of varicella vaccination

REFERENCES

- Takahashi M, Otsuka T, Okuno Y, et al. Development of varicella vaccine in Japan and future prospects. Vaccine 1994;12(14):1239–41. doi:10.1016/0264-410X(94)90242-9.

- Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI). Statement on a childhood varicella (chickenpox) vaccination programme; 2023 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/jcvi-statement-on-a-childhood-varicella-chickenpox-vaccination-programme

- BMJ Best Practice. Acute varicella-zoster: symptoms, diagnosis and treatment; last updated 2025. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/3000125

- NICE - Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Chickenpox: complications – background information; 2023 https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/chickenpox/background-information/complications/

- Ladhani SN, Guy R, Windram C, Ramsay ME. Burden of varicella complications in secondary care, England, 2004–2017. Eurosurveillance 2020;25(45):1900513. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.45.1900513.

- Mohanty S, Schwartz B, Gagneux-Brunon A, et al. Healthcare resource use and costs of varicella and its complications: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 2021;21(1):1207. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11226-3.

- Geddes L. Why don’t some countries vaccinate against chickenpox? BBC Future; 2019 Mar 13. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190312-why-dont-some-countries-vaccinate-against-chickenpox

- BBC News. Mum of girl who died from chickenpox welcomes vaccine plan; 2023 Sep 13. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-66797425

- Brisson M, Edmunds WJ, Gay NJ, et al. Estimated value of productivity lost due to childhood chickenpox in the United Kingdom: a survey of parents. PharmacoEconomics 2001;19(4):365–76. doi:10.2165/00019053-200119040-00006.

- Rodrigues F, Lartey S, Chatzopoulou D, et al. Varicella vaccination impact and cost-effectiveness in the United Kingdom: updated modelling analysis. Vaccine 2023;41(5):1110–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.12.011.

- Weinmann S, et al. Long-term impact of varicella vaccination on herpes zoster incidence. J Infect Dis 2023;228(3):421–9. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiac242.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Chickenpox in pregnancy (Green-top Guideline No. 13); 2022. https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/gtg-13-cpox.pdf

- NICE – Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Chickenpox: exposure to chickenpox – management; 2023. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/chickenpox/management/exposure-to-chickenpox/

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med 1965;58(1):9–20.

- Department of Health and Social Care. Varicella vaccine policy background [Archived content] https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

- UK Health Security Agency. Immunisation against infectious disease: Green Book, Chapter 28a – Shingles; 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/shingles-the-green-book-chapter-28a

- Forbes HJ, Bhaskaran K, Thomas SL, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with herpes zoster in England: a cross-sectional analysis of the Health Survey for England. BMC Infect Dis 2023;23(1):421. doi:10.1186/s12879-023-08457-9.

- NICE – Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Shingles: prevalence – background information; 2023. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/shingles/background-information/prevalence/

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Deaths in England in 2022 where shingles was cited as the primary cause; 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/

- Department of Health and Social Care. Shingles immunisation programme: information for healthcare professionals; 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/shingles-vaccination-guidance-for-healthcare-professionals/shingles-immunisation-programme-information-for-healthcare-practitioners

- Guerra FM, Bolotin S, Lim G, et al. The basic reproduction number (R₀) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17(12):e420–8. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30307-9.

- Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI). JCVI statement on a childhood varicella (chickenpox) vaccination programme; 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/childhood-varicella-vaccination-programme-jcvi-advice-14-november-2023/jcvi-statement-on-a-childhood-varicella-chickenpox-vaccination-programme

- Danechi S. Childhood Immunisation Statistics. Commons Library Research Briefing No. 8556. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8556/CBP-8556.pdf

- Chatzopoulou D, Lartey S, Rodrigues F. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of universal varicella vaccination in the UK. Vaccine 2023;41(2):250–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.01.027.

- Witte J, Buda S, Wicker S, et al. Trends in age-specific varicella incidences following the introduction of the general recommendation for varicella immunization in Germany, 2006–2022. BMC Public Health 2023;23(1):1871. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-16712-1.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Measles vaccines: WHO position paper, April 2017 – recommendations. Vaccine. 2019;37(2):219–22. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.09.053.

- Hungerford D, Campbell H, Brown K, Ramsay M. Impact of an accelerated measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine schedule on vaccine coverage: an ecological study among London children, 2012–2018. Vaccine 2020;38(47):7460–6. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.040.

- Danchin M, Koirala A, Crawford NW, et al. Timeliness of childhood vaccination in England: a population-based cohort study. Vaccine 2021;39(32):4604–12. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.06.026.

- Department of Health and Social Care. Introduction of a routine varicella (MMRV) vaccination programme for children at one year and at 18 months; 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/varicella-mmrv-vaccination-programme-announcement

Related articles

View all Articles