Vaccination hesitancy

Katherine Ellerby

Katherine Ellerby

RGN, RM, BSc (Hons),

Non-medical independent prescriber, NDFSRH

Practice Nurse, Framlingham Medical Practice, Suffolk & Clinical Research Nurse, Suffolk Primary Care

Practice Nurse 2021;51(2):10-15

Reluctance to accept vaccination is a very real issue in the UK, and in the current circumstances may have deadly consequences. But what is vaccine hesitancy and is there anything practice nurses can do to overcome it?

Vaccination saves lives. But according to the World Health Organization (WHO), vaccine hesitancy – the ‘delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services’ – was identified as one of the top ten threats to global health even before our world was consumed by the COVID-19 pandemic.1,2

As health professionals the influence we have as advocates of vaccination across all age groups to promote consistent evidence-based messages and advice cannot be underestimated.1 In the UK, vaccine hesitancy is a very real issue and as we attempt a vaccination campaign on an unimaginable scale, the consequences of a suboptimal uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine would have significant ramifications.

VACCINATION UPTAKE – THE FACTS

The good news is that despite the pandemic and restrictions of lockdown, coverage figures for routine childhood vaccinations in the UK during 2019-2020 have remained high.3 The European Region of WHO recommends that to achieve herd immunity – protecting those who can’t be vaccinated and prevent a resurgence of diseases in the population – at least 95% of children need to be immunised against vaccine-preventable diseases.3 Despite promising data with an increase in coverage of most routine vaccinations during the last year, uptake of childhood vaccinations, including the preschool booster and second dose of MMR, has not met the 95% target across many regions of the UK.3 NHS Digital’s Childhood Vaccination Coverage Statistics are a really useful guide for all GPNs to see what the situation is regionally and where uptake needs to be improved at a local level.3

Although uptake of influenza vaccine in England was up during the 2019-20 season for the over 65 year olds, the Public Health England annual report on influenza highlights that uptake for pre-school influenza and adults in clinical risk groups had decreased compared with previous years, most notably for patients with morbid obesity suggesting vaccine hesitancy within this cohort.4 Whilst the pandemic may well be responsible for the reduced uptake last year of the pertussis vaccine for pregnant women and, without doubt, the HPV vaccine for teenagers due to school closures, there are still evident gaps that need to be addressed.5-7

It is abundantly clear that throughout the UK, GPNs and practices are working extremely hard to achieve their immunisation targets for the national programmes. However, there clearly remain elements of vaccine hesitancy to a greater or lesser degree across the UK and this is the challenge many of us face. Add the roll out of COVID-19 vaccine into the mix and that challenge may feel even greater.

VACCINE HESITANCY

So what is behind the reluctance, resistance or even antipathy to embracing vaccination? It is certainly a very complex issue, but WHO simplifies it into three main factors.2

- Complacency

- Confidence

- Convenience

People who are complacent may believe that the risk of a vaccine-preventable disease is low and therefore the need to vaccinate, and the perceived risks associated with it, is unwarranted. We’ve all heard the ‘I had measles as a child and it never did me any harm’ or ‘no-one gets diphtheria any more’ arguments.

Confidence reflects the trust – or lack of it – in the safety and efficacy of vaccines, and the science that underpins them. Evidence suggests that the greater the mistrust in the science, the lower the uptake of vaccines.8 Conversely, areas of the world where vaccine-preventable diseases affect everyday life, the confidence in the safety and efficacy of vaccination and subsequent uptake is greater.8 Equally, a lack of confidence and distrust may be reserved for one particular vaccine or, for example, multi-dose presentations rather than vaccinations per se.9 In terms of childhood immunisations specifically ,GPNs may find themselves dealing with parents armed with ‘evidence’ which supports their beliefs and subsequent decisions not to have their children vaccinated.1

WHO also highlights the effect of convenience in accessing vaccines on uptake. Imagine having three children under 4 years and having to negotiate any number of buses to get the baby’s 8 week vaccines done. Or a controlling partner who won’t take you or let you have transport to take the twins for their preschool vaccines and you daren’t ask anyone else. Or the COVID-19 hub is just too far away to contemplate. So the baby, the 3-year-old twins and the elderly man who lives alone just don’t get their vaccines. Sometimes, for some people, the hurdles feel just too big to overcome, however much they believe in vaccination. And this is even without the additional fear many people have of attending practices or clinics during the pandemic, which is an additional contributing factor of vaccine hesitancy.10

THE COVID-19 VACCINE PROGRAMME AND VACCINE HESITANCY

So, is a vaccine against a virus which continues to wreak havoc on everyone’s everyday lives, with the wider consequences on morbidity and mortality rates, equally subject to vaccine hesitancy?

The OCEANS II online survey, undertaken prior to the programme roll-out, looked specifically at factors associated with vaccine hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccines in the UK.11 Over a quarter of the 5,000 plus participants who took part challenged the view that COVID-19 vaccines were considered safe and effective.11 Mistrust was based on perceptions that the vaccines were developed too quickly and therefore safety would have been compromised. Furthermore, for those resistant to having the vaccine, the risk of significant illness from COVID-19 was perceived to be negligible. The consequence of these beliefs not only affects an individual’s decision whether or not to have the vaccine but also can influence those who are more ambivalent or undecided. The result? Reduced vaccine uptake puts the more vulnerable people in society at greater risk.

On a positive note, almost three quarters of the population in the OCEANS II survey were happy to accept a COVID-19 vaccine and those with that opinion were more altruistic in prevention for the greater good rather than just considering vaccination from their own perspective.11 That's the key: tackling complacency and lack of confidence in the vaccine by sending out strong, positive and consistent messages, reassurance on safety and the benefits to society as a whole. However, the sheer logistics of vaccinating millions of people, especially those unable to access the vaccine at their own surgery, may potentially impact on the ease of getting vaccinated, particularly for the more elderly and vulnerable in society.12

HOW VACCINES ARE APPROVED FOR USE

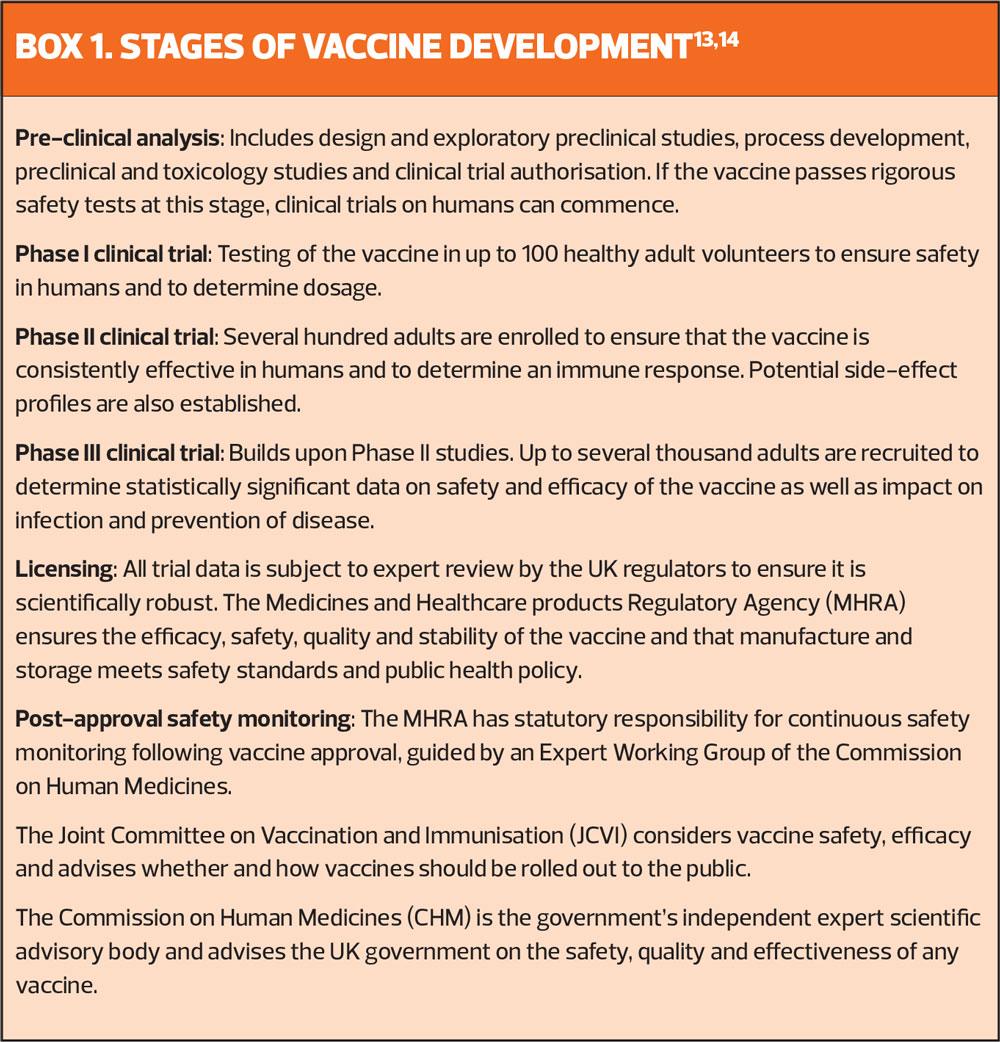

Perception of vaccine safety is intrinsically linked to vaccine hesitancy. The development of a vaccine can take in excess of 10 years and all vaccines used in the UK have undergone rigorous and extensive testing prior to approval.13 It is notable that there is a high failure rate of vaccines during clinical trials which is why, for example, there is still no vaccine for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).14

Crucial to any clinical trial is the protection of the rights, safety, wellbeing and dignity of the participants over and above the interest of science and society.15 The Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and the standards of International Conference on Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice Guideline (ICH GCP) underpin the ethical principles of conducting research and ensure the reliability and rigour of the scientific data.15 The stages of vaccine development within a clinical trial programme are outlined in Box 1.

In April last year the UK Government’s Vaccine Taskforce (VTF) was set up to establish a vaccine against COVID-19. Ordinarily, each stage of a clinical trial is run sequentially, one after the other. However, due to the gravity of the pandemic and its impact on human life globally, funding and the exceptional response of the research community have enabled the phases to be overlapped without any compromise to the intense rigour of the trials.14,16 Furthermore, the data has been expertly reviewed by the MHRA to verify safety and quality standards at each and every phase of the study, known as a rolling review, rather than on completion of the whole trial.

Usually, a vaccine manufacturer would apply to the MHRA or European Medicines Agency (EMU) for marketing authorisation, also known as the product licence. Changes to the Human Medicines Regulations 2012 has enabled the MHRA to enact Regulation 174 to temporarily authorise an unlicensed product in response to an identified public health risk in these exceptional circumstances.17 To date, three vaccines for COVID-19 have been given authorisation for temporary supply by the MHRA and UK Department of Health and Social Care under Regulation 174:18-20

- mRNA BNT162b2, Pfizer/BioNTech

- ChAdOx1nCoV-2019, Oxford-AstraZeneca

- mRNA-1273, Moderna

MHRA vaccine monitoring for safety and efficacy continues once the vaccines are in use with ‘real world’ data collected to monitor long term efficacy of the vaccine and determine any rare adverse events not seen in clinical trials. Patients and healthcare professionals can also contribute to this data by reporting any suspected adverse reactions via the MHRA Yellow Card scheme.21

MISINFORMATION, DISINFORMATION & MYTHS

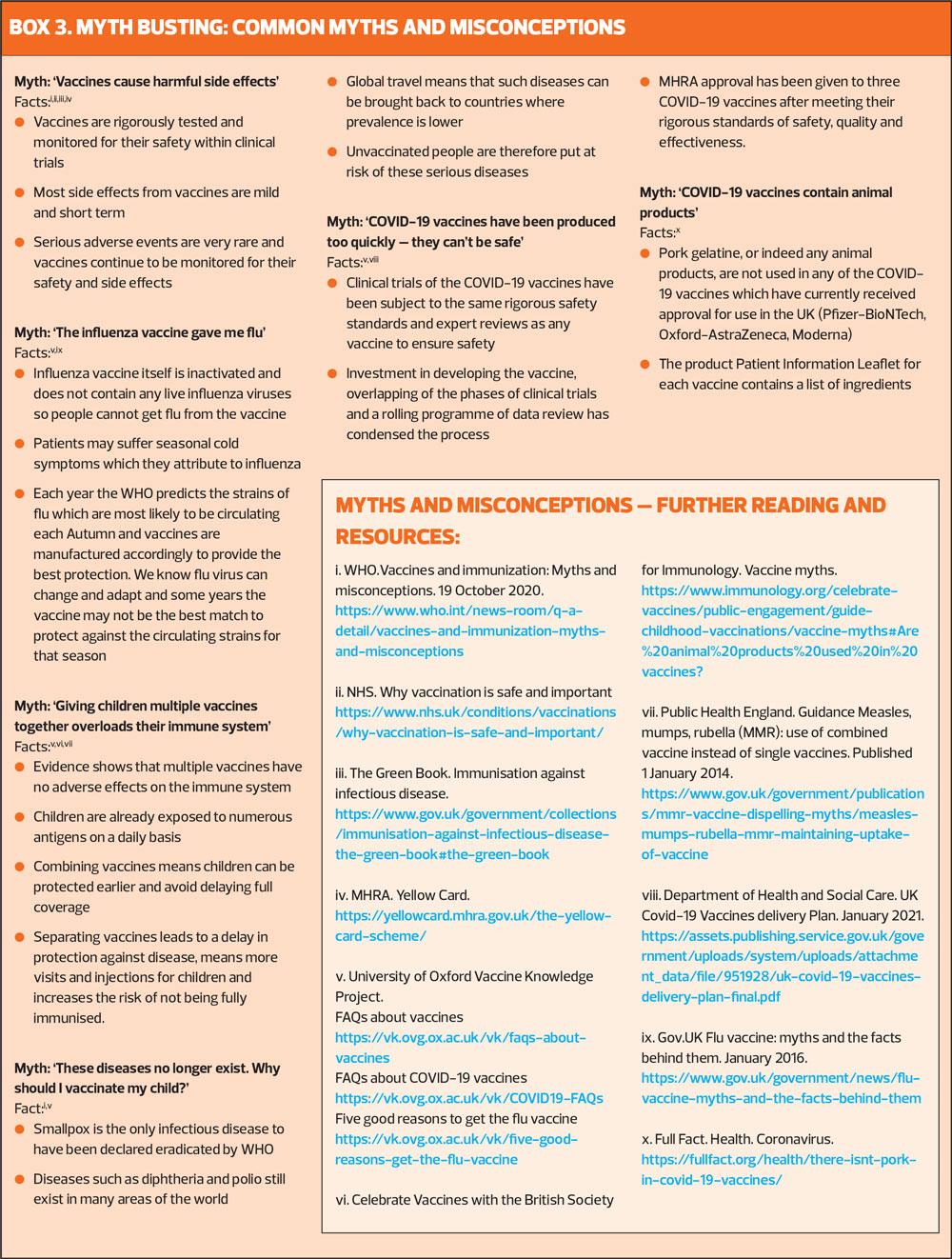

People are influenced by information circulating in society. In Victorian England it was opposition to smallpox vaccine that led to the formation of the anti-vaccination league in the mid 1800s.22 Today, we have social media to spread the word at lightening pace. Without doubt, people’s opinions and decision making can be significantly affected by the spread of unsubstantiated ‘evidence’ at one end of the scale through to ‘fake news’ at the other. One of the greatest vaccination controversies – the discredited claims of Dr Andrew Wakefield who was struck off the medical register after being found guilty of serious professional misconduct by suggesting the MMR vaccine was linked to an increased risk of autism and Crohn's disease through a hugely flawed ‘study’ – had a hugely detrimental impact on the uptake of the MMR vaccine in the late 1990s/2000s.23

In recent months, the hugely influential social media platforms have been awash with disinformation and misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines to confuse and mislead the public. While some of the claims have been simply outrageous, false messages regarding the contents of the vaccine as well as other misinformation regarding safety are of particular concern, and may be contributing to the low rate of vaccine uptake amongst certain black and minority ethnic groups. Clearly the implications of this may affect and impact whole communities.24

At the extreme end, anti-vaccination campaigners actively promote and spread fallacious content to propagate mistrust in the vaccines. Furthermore, this misinformation can eclipse evidence-based facts and public information and ultimately put the health of our nations at a significant risk.22

OVERCOMING VACCINATION HESITANCY AND IMPROVING UPTAKE

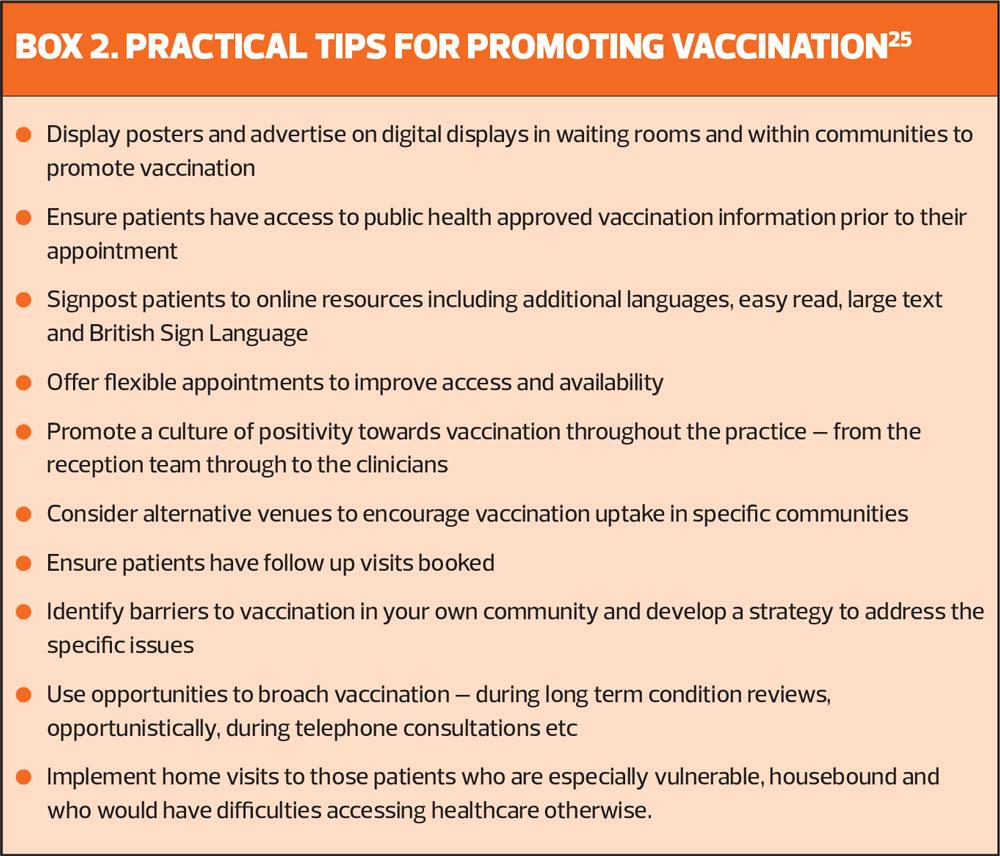

As GPNs we have a role to promote vaccination – whether it’s to a new parent or an older vulnerable person worried about COVID-19 – and counter misinformation for our patients who are vaccine-hesitant. Patients with really entrenched views against vaccination may be tricky to win round but those who are in two minds or simply misled by inaccuracies may be more receptive to discussion, facts and reason. So how can we approach this?25-27

- Be positive: knowledge, confidence and a positive attitude are critical to improving vaccine uptake.

- Know your patients: individuals and communities will have different perspectives in relation to vaccine hesitancy.

- Listen and show understanding: demonstrating respect and empathy for the patient’s/parent’s viewpoint can impact positively on vaccine acceptance.

- Ask questions without being confrontational: what are their concerns, what personal experiences have shaped their views, what information do they already have?

- Be knowledgeable: maintain your competence and keep your knowledge up to date. Know the evidence behind the facts and provide/direct to approved resources.

- Impart the facts: about safety and efficacy, acknowledge and dispel myths and misinformation and promote confidence in vaccines.

- Answer truthfully: give accurate and relevant evidence-based answers to questions.

- Be consistent: be aware of the current public health messages and guidance available to the public and avoid contradiction.

- Allow time: accept that patients and parents may need time to consider their options.

- Check understanding: confirm your message hasn’t been misconstrued or misunderstood.

MYTH BUSTING

There are often common themes GPNs face with regards to myths and misinformation regarding vaccination. BOX 3 answers some of the most common questions with links to evidence-based resources to support practice and to which patients can be directed. Additional useful resources to help the public to sift fact from fiction include the NHS website, Public Health England’s Facebook page which contains not only evidence-based multimedia posts but also myth debunking of circulating disinformation and also the Full Facts ‘fact checkers’ website.

CONCLUSION

It is good to have a curious mind, to explore, to weigh up risks and benefits. Being proactive in our health choices and examining the facts and reading around the subject is to be commended and often people who are vaccine-hesitant are doing just that. But it’s the quality and the accuracy of the information being accessed that is important and the impact of that information on confidence in the safety of the vaccines themselves which affects uptake. The success of any vaccination programme depends upon its uptake and in 2021 with the COVID-19 vaccine campaign well underway this is never more so relevant.

Clean water and vaccines are the two public health interventions which have had the greatest impact on the world’s health.28 In the UK we should be proud of our national immunisation programme. As GPNs our role is to continue to promote and maintain public confidence in vaccination in both our existing programmes and also by embracing the new vaccines that aim to reduce serious illness and death from COVID-19. Overcoming ambivalence, reluctance or an unwillingness to be vaccinated will be pivotal.11

REFERENCES

1. Editorial. Vaccine hesitancy: a generation at risk. The Lancet: Child and Adolescent health 2019;3(5):281 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanchi/article/PIIS2352-4642(19)30092-6/fulltext

2. World Health Organization: Ten threats to global health in 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

3. Public Health England. Childhood Vaccination Coverage Statistics England, 2019-20. 24 September 2020. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/31/DDCEC7/child-vacc-stat-eng-2019-20-report.pdf

4. Public Health England. Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in GP patients: winter season 2019 to 2020 Final data for 1 September 2019 to 29 February 2020. June 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/912099/Annual-Report_SeasonalFlu-Vaccine_GPs_2019-20_FINAL_amended.pdf

5. Public Health England. Pertussis vaccination programme for pregnant women update: vaccine coverage in England, July to September 2020. Health Protection Report. December 2020;14(23). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/941297/hpr2320_prtsss-vc.pdf

6. Public Health England. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage in adolescent females and males in England: academic year 2019 to 2020. Health Protection Report. October 2020;14(19). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/927694/hpr1920_HPV-vc.pdf

7. Public Health England. Pertussis vaccination programme for pregnant women update: vaccine coverage in England, April to June 2020 Health Protection Report. October 2020;14(20). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/929608/hpr2020_prtsss-vc.pdf

8. Fear of the needle.The Biomedical Scientist. 2019. https://thebiomedicalscientist.net/science/fear-needle

9. McKee C, Bohannon K. Exploring the reasons behind parental refusal of vaccines. J Paediatr Pharmacol Therap 2016; 21(2): 104–109. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4869767/

10. GP Online. GP fear surge of avoidable illness as patients skip routine vaccinations in pandemic. GP Online. 2 July 2020. https://www.gponline.com/gp-fear-surge-avoidable-illness-patients-skip-routine-vaccinations-pandemic/paediatrics/article/1688316

11. Freeman D, Loe BS, Chadwick A, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy in the UK: The Oxford Coronavirus Explanations, Attitudes, and Narratives Survey (OCEANS) II. Psychological Medicine. 2021:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0033291720005188

12. Public Health England. Guidance: Why you have to wait for your COVID-19 vaccine

Updated 15 January 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-vaccination-why-you-are-being-asked-to-wait/why-you-have-to-wait-for-your-covid-19-vaccine

13. Vaccine knowledge project. How vaccines are tested, licensed and monitored. Updated 11 January 2021. https://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/vk/vaccine-development

14. Department of Health and Social Security. UK Covid-19 Vaccines delivery plan. 11 January 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/951928/uk-covid-19-vaccines-delivery-plan-final.pdf

15. European Medicines Agency. Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Reference Guide 2016 Version 3.1; August 2016. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-e-6-r 2-guideline-good-clinical-practice-step-5_en.pdf

16. Public Health England. COVID-19 vaccination programme Information for healthcare practitioners Republished 31 December 2020 version 3 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/949063/COVID-19_vaccination_programme_guidance_for_healthcare_workers_December_2020_V3.pdf

17. Public Health England. COVID-19 Vaccination programme: Core training slide set for healthcare practitioners 31 December 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/covid-19-vaccination-programme#training-resources

18. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Decision. Information for Healthcare Professionals on Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine Updated 31 December 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-approval-of-pfizer-biontech-vaccine-for-covid-19/information-for-healthcare-professionals-on-pfizerbiontech-covid-19-vaccine

19. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Decision. Information for Healthcare Professionals on COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca

Updated 7 January 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-approval-of-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca/information-for-healthcare-professionals-on-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca

20. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Decision. Information for Healthcare Professionals on COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna. Updated 8 January 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-approval-of-covid-19-vaccine-moderna/information-for-healthcare-professionals-on-covid-19-vaccine-moderna

21. Public Health England. Surveillance and monitoring for vaccine safety: The Green Book, chapter 9. March 2013. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/147870/Green-Book-Chapter-9.pdf

22. Royal Society and the British Academy. COVID-19 vaccine deployment: Behaviour, ethics, misinformation and policy strategies; 21 October 2020.

https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/set-c/set-c-vaccine-deployment.pdf

23. Godlee F, Smith J, Marcovitch H. Wakefield’s article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent. BMJ 2011;342:c7452. https://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.c7452

24. Haynes L. GPs raise alarm over low uptake of COVID-19 vaccine in BAME patients.19 January 2021. https://www.gponline.com/gps-raise-alarm-low-uptake-covid-19-vaccine-bame-patients/article/1704790

25. National Minimum Standards and Core Curriculum for Immunisation Training for Registered Healthcare Practitioners Revised February 2018.

26.Thompson A, Vallée-Tourangeau G, Suggs S. Strategies to increase vaccine acceptance and uptake: From behavioral insights to context-specific, culturally-appropriate, evidence-based communications and interventions. Vaccine 2018;36:6457-6458

27. Hazel T. Immunisation and Vaccination. Top tips: vaccination myth-busting. Guidelines in Practice. Available at: https://www.guidelinesinpractice.co.uk/immunisation-and-vaccination/top-tips-vaccination-myth-busting/455064.article

28. Public Health England. Immunisation. January 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation

Related articles

View all Articles