Providing sexual and reproductive healthcare in general practice

Katherine Hunt

Katherine Hunt

RGN, RM, BSc(Hons)

Non-medical independent prescriber, NDFSRH

Practice Nurse, Framlingham Medical Practice, Suffolk

Historically, much of the work relating to women’s health in general practice fell to female GPs. Now, it is more likely to be the general practice nurse who shoulders most of the workload relating to contraception and sexual health

The essence of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is to provide safe and effective contraception to enable people to make the choice when, and when not, to have children; to promote the prevention, as well as treatment, of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs); and to promote safe and healthy sexual relationships. Managing SRH in primary care is a specialty, which may be unfamiliar to nurses new to general practice. This article aims to address some of the essential elements of SRH that nurses can gain competence and confidence in. This includes:

- Discussing SRH issues with patients

- Undertaking repeat contraceptive checks for women already taking oral or injectable contraception

- Assessing whether a woman is at risk of pregnancy

- Offering all emergency contraception options and signposting appropriately

- Providing resources for all methods of contraception for women to make an informed choice

- Undertaking a risk assessment to determine if a patient is at risk of a sexually transmitted infection (STI)

- Undertake screening in asymptomatic patients

- Determining whether a patient has any symptoms of an STI

- Providing further information and signposting to colleagues or specialist SRH services

SEXUAL HISTORY TAKING

Obtaining an accurate and honest sexual history can be challenging. However, assessing someone’s risks of STIs, pregnancy, their contraceptive needs and sexual wellbeing means we are able to offer them, or signpost them to, the most appropriate care. This can sometimes be harder for patients in a GP surgery compared with those who select to go to a specialist sexual health setting.

Consider the teenager who attended with their Mum the previous week for travel vaccines who now appears awkwardly at your door wanting to join the free condom scheme. They have to admit that they are having sex and, for them, it’s excruciatingly embarrassing. Confidentiality is paramount, and patients need to be reassured that their confidentiality will be maintained with the caveat that disclosure may be necessary in certain circumstances where there are concerns for an individual’s safety, or indeed in the public’s interest.1

Sometimes patients bring along friends or family members as support but it is pertinent to clarify whether they are happy to talk about intimate details in front of their companion. As health professionals we assure our confidentiality – but is your patient happy their friend can do the same? Taking a welcoming approach and explaining why it is necessary to ask certain questions can help patients to talk about sensitive issues. General Practice Nurses (GPNs) themselves need to feel comfortable about broaching sexual health issues, refraining from showing judgement or making assumptions. Starting with less intrusive questions, clarifying terms and gaining a patient’s permission to enquire about their sex lives can help to gain the patient’s confidence before moving into a discussion about more sensitive and specific sexual behaviour. The 2013 UK National guideline for consultations requiring sexual history taking1 provides an excellent resource for best practice. Patients with psychosexual issues will need expert consultation but patients may use times, such as during routine cervical screening, to divulge particular concerns. All incidences of sexual assault must be referred to a Sexual Assault Referral Centre in line with local policy. Any evidence of female genital mutilation will equally need to be dealt with sensitively and referred appropriately as per local and national guidance.2

CONTRACEPTION ESSENTIALS

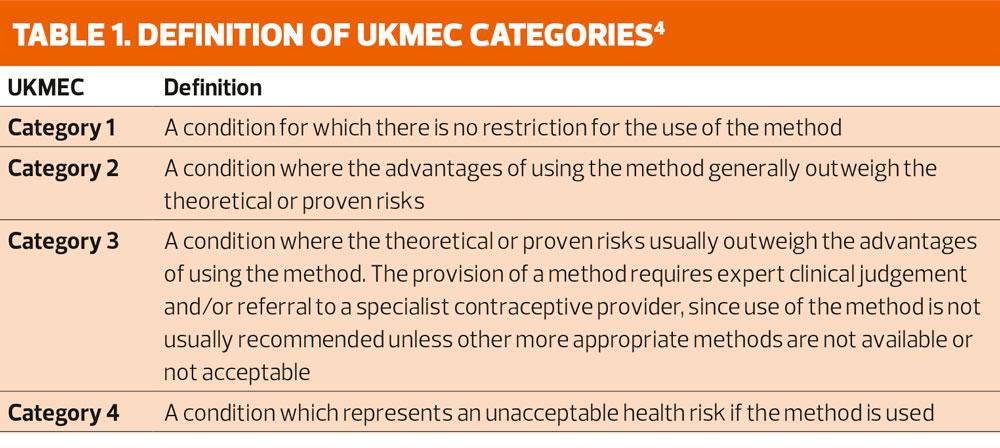

Undertaking repeat reviews for women already taking oral hormonal contraception and continuing injectable contraceptives is a good starting point. The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare’s method-specific Clinical Guidance and The UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (UKMEC) underpins practice in the delivery of contraceptive care.3,4 The UKMEC provides guidance on the safe use of contraception for women. Table 1 shows the definition of the UKMEC categories. It allows clinicians to make decisions from evidence-based recommendations for women with specific medical conditions, which may be associated with a potential health risk when certain contraceptives are used. All women must be thoroughly assessed to determine suitability and safety for any method but the guidance should also be used in contraceptive reviews to determine whether the patient can continue to use their chosen method safely. The FSRH Clinical Guidance document on drug interactions, the British National Formulary (BNF) and drug interaction checkers, such as MEDSCAPE, are useful tools for determining medication interactions.5-7

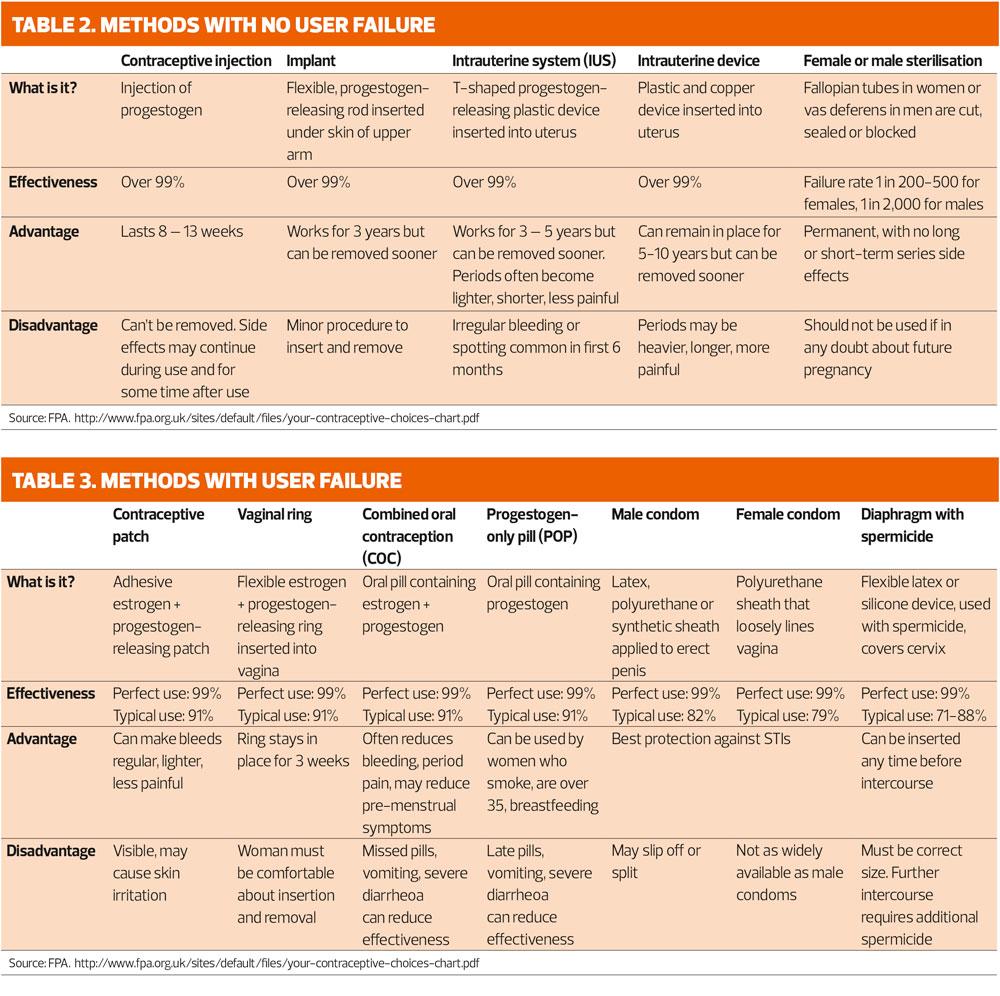

GPNs need to have a ‘working knowledge’ of all methods of contraception and be conversant with the advantages and disadvantages of each contraceptive method and give an overview of how they work. Websites such as NHS choices and the FPA charity provide useful resources to share with patients. Tables 2 and 3 give a summary of each method. Specifically, we will address the ‘pill check’ and repeat injections for women already using Combined Hormonal Contraception and Injectables.

Combined Hormonal Contraception (CHC) overview

Combined Hormonal Contraception is taken either as an oral pill (COC), a transdermal patch (CTP) or a vaginal ring (CVR). Containing a combination of estrogen and progestogen, they inhibit ovulation, thicken cervical mucus and thin the endometrium to contraceptive effect. A safe and effective method for many women, there are nevertheless some medical conditions and lifestyle factors which may contribute to health risks with CHC, such as risk factors for venous thromboembolism and cardiovascular disease, migraines, smoking and being overweight.4 Traditionally, combined oral contraception (COC) is taken daily for 21 days followed by a 7 day break (or 7 placebo pills) to allow for a withdrawal bleed, similar to a period. The weekly transdermal patch, applied to clean dry skin every week for 3 weeks, and the vaginal ring – which is inserted for 3 weeks – follow the same pattern of 21 days of hormonal contraception and a 7 day hormone-free interval. However, tailored regimes where the hormone is continued for an extended period with a shorter hormonal free interval reduces the number of bleeds a woman has each year as well as improving efficacy.8 This can be achieved through specific licenced COCs (Zoely or Qlaira) or by extended use of the pill, patch or ring by increasing the number of hormonal days and reducing the number and duration of the hormone-free interval. This practice, although off-licence, is supported by the FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit.8

Progestogen-only Pill (POP) overview

The continuous daily POP contains one of three progestogens – desogestrel 75mcg, levonorgestrel (LNG) 30mcg or norethisterone (NET) 350mcg. Desogestrel suppresses ovulation in 97% of cycles, with the traditional LNG and NET pills having a much more limited effect on ovulation suppression, relying more on the effect of progestogen on thickening cervical mucus to prevent sperm penetration.9 As with the COC, the POP needs to be taken consistently at a similar time each day. If forgotten, the desogestrel POP has a 12-hour window – just like the COC, whereas traditional POPs should be taken within 3 hours from the time it should have been taken to preserve contraceptive effect. Unscheduled vaginal bleeding can be a major issue for some women although many enjoy amenorrhoea with the POP. Side effects can include mood changes, effect on libido, breast tenderness and acne.

CHC and POP contraceptive checks

Repeat checks for women already taking CHCs or POPs are recommended either 6 or 12 monthly, depending on local policy. Continuation of the method is dependent on acceptability, medical and drug history, side effects and general health. It also provides the opportunity to ensure the patient is up to date with cervical screening and is familiar with breast awareness. Areas to discuss as part of the routine check include:

- Concordance: is the method being taken correctly, does she miss pills and if so, know what action to take? Is she aware of emergency contraception? Does she understand why episodes of vomiting or severe diarrhoea can reduce efficacy?

- What is the bleeding pattern like: does she have a regular withdrawal bleed in the hormone-free interval? Is there any abnormal vaginal bleeding such as break through bleeding or bleeding after sex? Do you need to consider STI screening or further investigation?

- Lifestyle factors: In relation to CHC, does she smoke, and if so, how old is she and how many a day? CVD risks increase with advancing age and smoking. What is her BMI?

- Sexual history: explore partner history, condom use, infection risk and assess any urinary, vaginal, anal and oral symptoms (as appropriate)

- Medical history: For CHC, is her blood pressure raised? Has there been in change in medical history since the contraception was initially prescribed? If so, refer to UKMEC guidance and colleagues for advice.

- Warning signs CHC: has there been any breathlessness, chest pain or haemoptysis? Has she developed migraines and if so explore any symptoms of aura.3 Has she had any calf pain, swelling or tenderness? If so, immediate referral to a clinician is essential.

- Side effects: what is she experiencing, if any? Are the side effects tolerable? How can they be managed? Would another method or type of hormonal contraception be more suitable? Are they contraceptive related?

- Medication: has she commenced any new medication including over-the-counter or herbal medication, in particularly St John’s wort or student ‘smart’ drugs such as Modafinil which may interact with, and reduce contraceptive efficacy?

Progestogen-only injectable (POI) contraception overview

Progestogen-only injectables belong to the family of Long Acting Reversible Contraceptives (LARCS) which are not user-dependent and therefore give greater peace of mind for women who forget pills or in whom CHC is contraindicated. Essentially, they inhibit ovulation, affect cervical mucus to prevent sperm penetration and render the endometrium unsuitable for implantation. They can cause amenorrhoea, as well as irregular bleeding patterns, with side effects similar to the POP. Injection site reactions can occur with the subcutaneous presentation. They can also be of benefit to patients with endometriosis, dysmenorrhoea and heavy menstrual bleeding. There are 3 types of injectable contraceptives available and are given at 12, 8 and 13 weeks, respectively:

- Depo Provera (IM DMPA): Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) 150mg/1ml IM injection

- Sayana Press (SC DMPA): MPA 104mg/0.65ml subcutaneous injection

- Noristerat (NET-EN): Norethisterone enantate 200mg/1ml IM injection (less frequently used)

There is an association with minor bone mineral density loss with DMPA, which recovers after discontinuation of the method, and all women should review the risks and benefits of the method every two years. Women also need to be advised of a potential delay in return to fertility up to one year after stopping DMPA although not to rely on this delay as a contraceptive. FSRH guidance details what action to take if a patient is late presenting for injection (or when switching from another contraceptive to an injectable).10 For patients attending for repeat injections, assessment should include the following:

- Checking the date the last injection was given to ensure continued protection, pregnancy risk and/or need for emergency contraception

- Update medical history in relation to UKMEC

- Check for drug interactions and contraindications with drug interaction resources

- Ascertain side effects including abnormal bleeding patterns, refer to colleagues accordingly

- Determine the need for sexual health screening

- Review BP and BMI annually

- Check if planning a future pregnancy to consider alternative contraceptive needs in the interim

- Review bone density risk two yearly

- Determine the date of the next injection and make the appointment

Sayana Press, the SC DMPA, is licenced for self-administration and provides an additional convenience for women.

Fraser guidelines and Gillick competence

Gillick competence applies to the capacity of young people under 16 to consent to their own treatment. Fraser guidelines are concerned specifically with contraception in relation to under-16s. GPNs must be happy that the young person receiving advice and treatment meets the following criteria on each occasion:11

- They understand the advice being given

- They cannot be convinced to involve their parents/carers or allow the health professional to do so on their behalf

- They will begin or continue to have sex with or without contraception

- Unless they receive treatment or contraception their physical and/or mental health is likely to suffer

- It is in their best interest to be given contraceptive advice, treatment or supplies without parental consent

Particular awareness and sensitivity is required when supporting people with learning disabilities. GPNs also need to be familiar with the law on sexual activity with regards to young people. The FPA fact sheet ‘The Law on Sex’ provides a summary of key points in the UK.12 Any concerns of sexual exploitation or abuse, whatever age, must be referred according to local safeguarding policy.

SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS (STIs)

STIs are a public health issue. Frequently without symptoms, they can be readily transmitted from one person to another, with potential long-term sequelae. Screening for often asymptomatic infections such as chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis and HIV enables identification, treatment and prevention of complications as well as transmission. Younger people, aged 15-24, have the highest proportion of STIs with 61% of those with chlamydia in this age group and many practices may be involved in both the National Chlamydia Screening Programme and condom schemes for the under-25s.13,14 The British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) provides guidance for the identification and management of all STIs, as well as useful downloadable patient information leaflets.15 Although candida and bacterial vaginosis (BV) can both be causes of vaginal discharge, they are not classed as STIs and do not require treatment unless the patient is symptomatic.

Sexual history-taking is necessary to determine whether the patient has any symptoms, the timing and type of exposure, to identify any high risk partners and if the sexual activity was consensual. Condom and contraceptive use also should be ascertained. Details of tests for STI in asymptomatic men and women are given in the 2015 BASHH CEG guidance (https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1084/sti-testing-tables-2015-dec-update-4.pdf)

Testing too soon after exposure may give false negative results. All patients must give informed consent prior to testing and arrangements must be made for how patients receive their results.

Symptomatic patients should be referred to colleagues prior to offering testing for further examination and/or referral to sexual health providers depending on the expertise within the practice. Symptoms include:

- Unusual or purulent vaginal or penile discharge

- Genital irritation or skin problems

- Genital ulceration

- Females – pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, unusual vaginal bleeding including post-coital bleeding or intermenstrual bleeding

- Males - testicular pain and swelling

- Dysuria

- Perianal symptoms

PREGNANCY RISK AND EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION

Unprotected sexual intercourses (UPSI) – when no contraception has been used or used incorrectly – may result in pregnancy. In essence this includes:16

- UPSI on ANY day of the natural menstrual cycle

- UPSI from day 21 after childbirth (unless meets the criteria for lactational amenorrhoea, as per FSRH method guidance)

- UPSI after 5 days following termination of pregnancy, miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, uterine evacuation for gestational trophoblastic disease

- Women using hormonal contraception either incorrectly or if compromised by interacting medication or vomiting.

The three methods of emergency contraception (EC) available in the UK are:

- A copper IUD (Cu-IUD)

- An oral, single dose of ulipristal acetate (UPA) 30 mg licenced up to 120 hours post UPSI

- An oral, single dose of levonorgestrel (LNG) 1.5 mg licenced up to 72 hours post UPSI.

Oral EC is effective by delaying ovulation therefore is unlikely to work if more than 120 hours has elapsed since the last UPSI or if ovulation has already taken place. All women should consider the emergency Cu-IUD, which can be inserted within 5 days after the first UPSI in a cycle or within 5 days of the estimated date of ovulation on the shortest cycle. The 2017 FSRH Guideline on Emergency Contraception gives clear guidance, as well as decision-making algorithms, to guide the use and choice of EC. Offering EC is not always straightforward as it is dependent on cycle length and variability, episodes of UPSI, calculation of date of ovulation, body mass index, concomitant drugs and the efficacy of the type of EC in preventing pregnancy – as well as the accuracy of the history! The Cu-IUD is ten times more effective than oral EC and provides ongoing contraception. If oral EC is given, continuing contraception also must be addressed in line with FSRH guidance.16 The same oral EC can be used more than once in a cycle and patients also need to be aware that it can be accessed through pharmacies, although a charge may apply.

CONCLUSION

It is without doubt that sexual and reproductive health is a huge specialty in itself, but being able to at least offer patients the basics of contraceptive care and STI screening, providing supportive resources, signposting to local agencies and recognising when and where to refer are all part of the competencies for GPNs.17 Acquiring and extending knowledge and skills by undertaking formal training and study days increases our competence and confidence in SRH for both ourselves and our patients.

FURTHER READING AND RESOURCES

FSRH UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (UKMEC) evidence based guidance to determine safe use of contraception www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/uk-medical-eligibility-criteria-for-contraceptive-use-ukmec/

FSRH - Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Health current clinical guidance

www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/current-clinical-guidance/

FPA - the sexual health charity

BASHH British Association for Sexual Health and HIV – guidelines

MENCAP Relationships and Sex

www.mencap.org.uk/advice-and-support/relationships-and-sex

NSPCC A child’s legal rights: Gillick competency and Fraser guidelines

NHS Choices Sexual health topics

www.nhs.uk/Livewell/Sexualhealthtopics/Pages/Sexual-health-hub.aspx

RCGP Sexually Transmitted Infections in Primary Care 2013

Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare e-learning Programme accessed via e-Learning for Healthcare

Terence Higgins Trust

The STI Foundation

CASE STUDIES – ANSWERS AND DISCUSSION

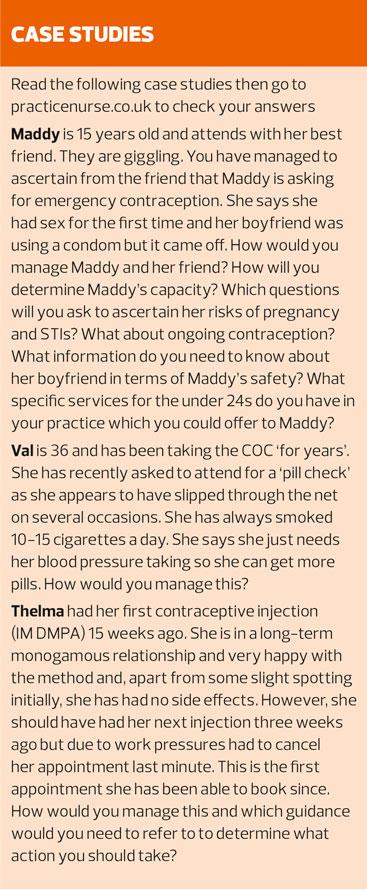

Maddy

Confidentiality and history taking: Consider having the consultation with Maddy without her friend being present so you can get a direct account from Maddy for the sexual history.

Safeguarding: Determine the age of Maddy’s boyfriend. Was the sex consensual? How do Maddy and her boyfriend know each other – are they friends of a similar age at school or have they met online? Is there a large age discrepancy? Is her ‘boyfriend’ in a position of trust?

FPA ‘The Law on Sex’ http://www.fpa.org.uk/factsheets/law-on-sex#age-consent

HM Government, What to do if you’re worried a child is being abused. Advice for practitioners. March 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/419604/What_to_do_if_you_re_worried_a_child_is_being_abused.pdf

Capacity: Are you satisfied that Maddy meets the criteria of the Fraser guidelines in relation to contraceptive care and is also ‘Gillick competent’ to provide consent.

NSPCC A child’s legal rights: Gillick competency and Fraser guidelines https://www.nspcc.org.uk/preventing-abuse/child-protection-system/legal-definition-child-rights-law/gillick-competency-fraser-guidelines/

Sexual history: It is important to put Maddy at ease. Explain why it is necessary to ask sensitive questions to give Maddy the most appropriate care. You will need to confirm that this was in fact Maddy’s first sexual encounter and to establish that it was penetrative vaginal sex. You will need to enquire whether she also had oral/anal sex as well to determine additional infection risk. You want to ascertain if her boyfriend has had sex before or is it is also his first time to assess the need for STI screening. It is also important confirm when the sexual activity took place so you can calculate the timing for taking swabs if deemed necessary by the sexual history.

Brook G, Bacon L, Evans C et al 2013 UK National guideline for consultations requiring sexual history taking. Clinical Effectiveness Group British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2013 0(0) 1-14

STI screening: As this was in fact Maddy’s first sexual encounter, you could make her appointment to return for STI screening in two weeks for self-test low vaginal swab if asymptomatic. Seeing her again would allow you to assess her to see if she has any symptoms. You could provide Maddy with a self-test postal chlamydia kit although you would need to impress on her that she should return if she has any symptoms. Is Maddy likely to do this?

BASHH CEG Guidance on tests for Sexually Transmitted Infections. BASHH Clinical Effectiveness Group April 2015 (amended December 2015) https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1084/sti-testing-tables-2015-dec-update-4.pdf

Terence Higgins Trust. Young and Free. https://www.tht.org.uk/sexual-health/Young-people/Young-and-Free

Public Health England. Opportunistic Chlamydia Screening of Young Adults in England. An Evidence Summary. April 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/497371/Opportunistic_Chlamydia_Screening_Evidence_Summary_April_2014.pdf

Pregnancy risk/Emergency Contraception: As Maddy has had unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI), the FSRH guidance (below) advises that emergency contraception is indicated if UPSI has taken place on ANY day of a natural menstrual cycle. Therefore Maddy should be offered emergency contraception. You will need to establish Maddy’s menstrual cycle; her likeliest date of ovulation; how many days have elapsed since Maddy had sex; has she had any further UPSI she hasn’t previously told you about; has UPSI occurred within 5 days prior to the estimated date of ovulation?

Are you able to offer emergency copper intrauterine device (Cu-IUD) within your own practice – if not, you will need to know the referral pathway for patients to access this in your local area. By offering to fit a Cu-IUD you will be able to provide Maddy with the most effective emergency contraception plus on-going contraception. If this is not acceptable to Maddy you will need to consider oral emergency contraception. You establish that Maddy had only one episode of UPSI 16 hours ago, she is day 5 since her last menstrual period and her cycle is roughly every 28-35 days. She has no medical history of note and takes no medication including herbal or over the counter. Her BMI is 20 kg/m2. Ulipristal acetate (UPA) is more effective but consideration of ongoing contraception would need to be taken into account. If she is given UPA-EC, she would need to wait 5 days before commencing another hormonal contraceptive to ensure the EC is effective plus would require additional precautions until that contraceptive is effective. As the UPSI has taken place more than 5 days prior to estimated ovulation, oral levonorgestrel emergency contraception (LNG-EC) may be more appropriate so that Maddy can also quick-start hormonal contraception thus reducing further risk of UPSI and pregnancy. As she has a BMI under 26mg/m2 there would be no need to double up the dose of LNG-EC. It would be prudent to offer Maddy an appointment in 3 weeks to undertake a pregnancy test to ensure that the EC has worked (this could also be tied in with STI screening).

Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Clinical Guidance. Emergency Contraception. March 2017. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/current-clinical-guidance/emergency-contraception/

Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Clinical Guidance. Quick starting contraception. April 2017. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/current-clinical-guidance/quick-starting-contraception/

Ongoing Contraception: Choice of emergency contraception may dictate ongoing contraception, as detailed above. You will need to provide Maddy with details and information on all methods of contraception for her to make an informed choice. If Maddy does not opt for an emergency Cu-IUD, Maddy can quick start the following methods of contraception:

Combined hormonal contraception (except cyproterone acetate containing COC)

- Progestogen-only pill

- Progestogen subdermal implant

- Depo-provera injectable contraceptive

After LNG-EC, the above methods can be started immediately. If UPA-EC is given, Maddy will need to wait 5 days before quick-starting any of the above methods. In both cases extra precautions, as per method guidance, may need to be taken until the new method becomes effective if more than day 5 from the last menstrual period. As pregnancy cannot be reasonable excluded, the LNG-IUS devices (Mirena and Jaydess) cannot be quick started.

Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Clinical Guidance. Quick starting contraception. April 2017. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/current-clinical-guidance/quick-starting-contraception/

Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Standards and Guidance: Method specific. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/current-clinical-guidance/method-specific/

Specific services: Does your practice participate in the National Chlamydia screening programme (see notes STI screening) and a condom scheme for under 25s? If not, direct patients to free condom schemes in your area by signposting Maddy to websites such as NHS choices, Terence Higgins Trust or Brook. Discussing the prevention od STIs with Maddy is important.

NHS choices for condoms and STI advice

NHS choices chlamydia testing http://www.nhs.uk/Service-Search/Chlamydia%20-%20free%20online%20tests%20for%20u-25s/LocationSearch/344

Terence Higgins Trust http://www.tht.org.uk/sexual-health/Improving-your-sexual-health/Condoms/Using-a-condom and https://www.tht.org.uk/sexual-health/Young-people/Young-and-Free

Brook: sexual health and wellbeing for the under 25s https://www.brook.org.uk/your-life/category/stis

Val

You establish Val has had no medical problems since her last review and is not on medication although takes the occasional multi-vitamin. After taking a sexual history you establish she is not currently at risk of STIs. She is a good pill taker and doesn’t miss pills. Her blood pressure is normotensive and her BMI is 23kg/m2.

You will need to check the FSRH UK Medical Eligibility Criteria to determine whether the COC is still suitable for Val as part of her review. Use of Combined Hormonal Contraception and smoking increases a woman’s risk of cardiovascular disease, especially myocardial infarction. Up until the age of 35 years, smoking with the COC is given a UKMEC category 2, i.e. ‘A condition where the advantages of using the method generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks’. However, Val is now 36 years and continues to smoke. This gives her a UKMEC of 3, ‘A condition where the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using the method’. Her risks of CVD, and associated mortality, are now significantly increased. Clearly, you need to address smoking cessation but certainly Val will now need to consider an alternative method of contraception. You will need to provide information and resources on other methods which may be suitable for Val, pointing out the benefits to her health. She could consider progestogen-only contraception or any of the Long Acting Reversible Methods. You could provide her with a desogestrel POP for immediate use whilst she considers all the options. Val has always liked cycle control therefore you will need to discuss the implications of the other methods on her bleeding pattern.

Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. UK MEC 2016. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ukmec-2016/

Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Standards and Guidance: Method specific. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/current-clinical-guidance/method-specific/

FPA. Leaflet and booklet downloads – contraceptive methods. http://www.fpa.org.uk/resources/leaflet-and-booklet-downloads

Thelma

Thelma is clearly happy with her method and has no risk factors for STIs and now has amenorrhoea. She would like to continue with injectable contraception. The FSRH provide advice in relation to patients who present late for their injections (see below). As Thelma is more than 14 weeks and 1 day since her last DMPA injection you will need to ascertain whether or not there has been a risk of pregnancy in the last 7 days. Has she had Unprotected Sexual Intercourse (UPSI) since week 14 from the date of her injection? If not, she is not at risk of pregnancy, does not need emergency contraception and can be given her DMPA injection but will need additional contraception (or abstinence) over the next 7 days. There would be no need for a pregnancy test.

However, if she has had sex in the last week you will need to ascertain when it was and if there were multiple episodes. You will need to offer a bridging method such as POP/CHC until you confirm she is not pregnant, or even consider giving the DMPA off-licence as per FSRH guidance, with 7 days additional precautions. You will need to consider which Emergency Contraception is most appropriate based on how long ago she had UPSI. A pregnancy test will be required 3 weeks after the last UPSI. Table 4 in the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare advice in relation to late progestogen-only contraceptive injections in the guidance document below provides clear advice in managing late presentations for injectable contraception.

Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Clinical Guidance. Progestogen-only Injectable Contraception. December 2014. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/cec-ceu-guidance-injectables-dec-2014/

REFERENCES

1. Brook G, Bacon L, Evans C et al 2013 UK National guideline for consultations requiring sexual history taking. Clinical Effectiveness Group British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2013 0(0) 1-14

2. H M Government. Multi-agency statutory guidance on female genital mutilation. April 2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/512906/Multi_Agency_Statutory_Guidance_on_FGM__-_FINAL.pdf

3. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Standards and Guidance: Method specific. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/current-clinical-guidance/method-specific/

4. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. UK MEC 2016. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ukmec-2016/

5. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Drug Interactions with Hormonal Contraception. January 2017. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-drug-interactions-with-hormonal/

6. Medscape Drug Interaction Checker Available at: http://reference.medscape.com/drug-interactionchecker

7. Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (online) London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press

8. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Clinical Guidance. Combined Hormonal Contraception. Updated August 2012. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/combined-hormonal-contraception/

9. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Clinical Guidance. Progestogen-only pills. March 2015. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/cec-ceu-guidance-pop-mar-2015/

10. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Clinical Guidance. Progestogen-only Injectable Contraception. December 2014. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/cec-ceu-guidance-injectables-dec-2014/

11. NSPCC. A child’s legal rights: Gillick competency and Fraser guidelines. https://www.nspcc.org.uk/preventing-abuse/child-protection-system/legal-definition-child-rights-law/gillick-competency-fraser-guidelines/

12. FPA. The law on sex. Last updated April 2015. Available at: http://www.fpa.org.uk/factsheets/law-on-sex

13. Public Health England. Sexually transmitted infections in England. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/536208/STI_poster.pdf

14. Public Health England. Opportunistic Chlamydia Screening of Young Adults in England. An Evidence Summary. April 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/497371/Opportunistic_Chlamydia_Screening_Evidence_Summary_April_2014.pdf

15. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. BASHH guidelines. https://www.bashh.org/guidelines

16. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Clinical Guidance. Emergency Contraception. March 2017. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/current-clinical-guidance/emergency-contraception/

17. Royal College of General Practitioners General Practice Foundation/ Royal College of Nursing. General Practice Nurse Competencies. December 2012 (updated May 2015).

Related articles

View all Articles