Recognising sepsis

Dr Gerry Morrow

Dr Gerry Morrow

MB ChB, MRCGP, Dip CBT

Medical Director Clarity Informatics and Editor Clinical Knowledge Summaries

Practice Nurse 2021;51(2):28-33

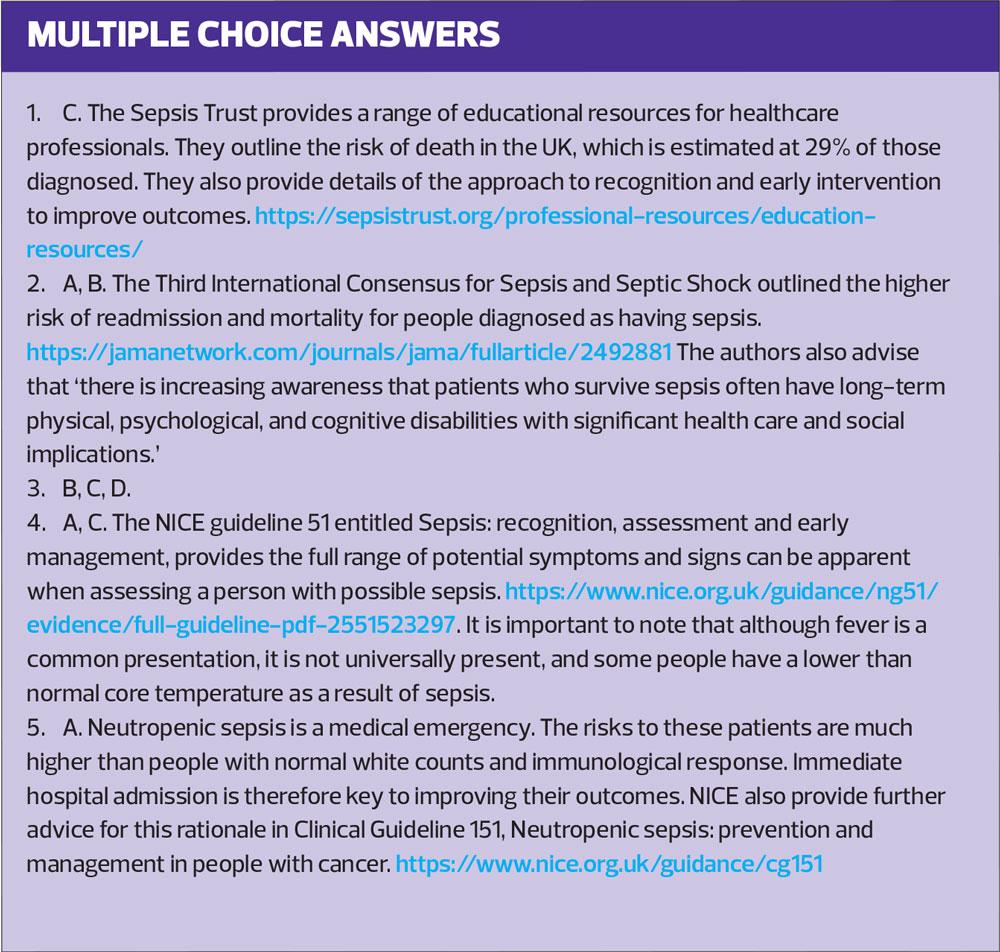

The incidence of sepsis is increasing. The condition carries a high mortality rate and, for survivors, is associated with long-term physical, psychological and cognitive impairments. Early recognition and prompt, aggressive treatment is essential

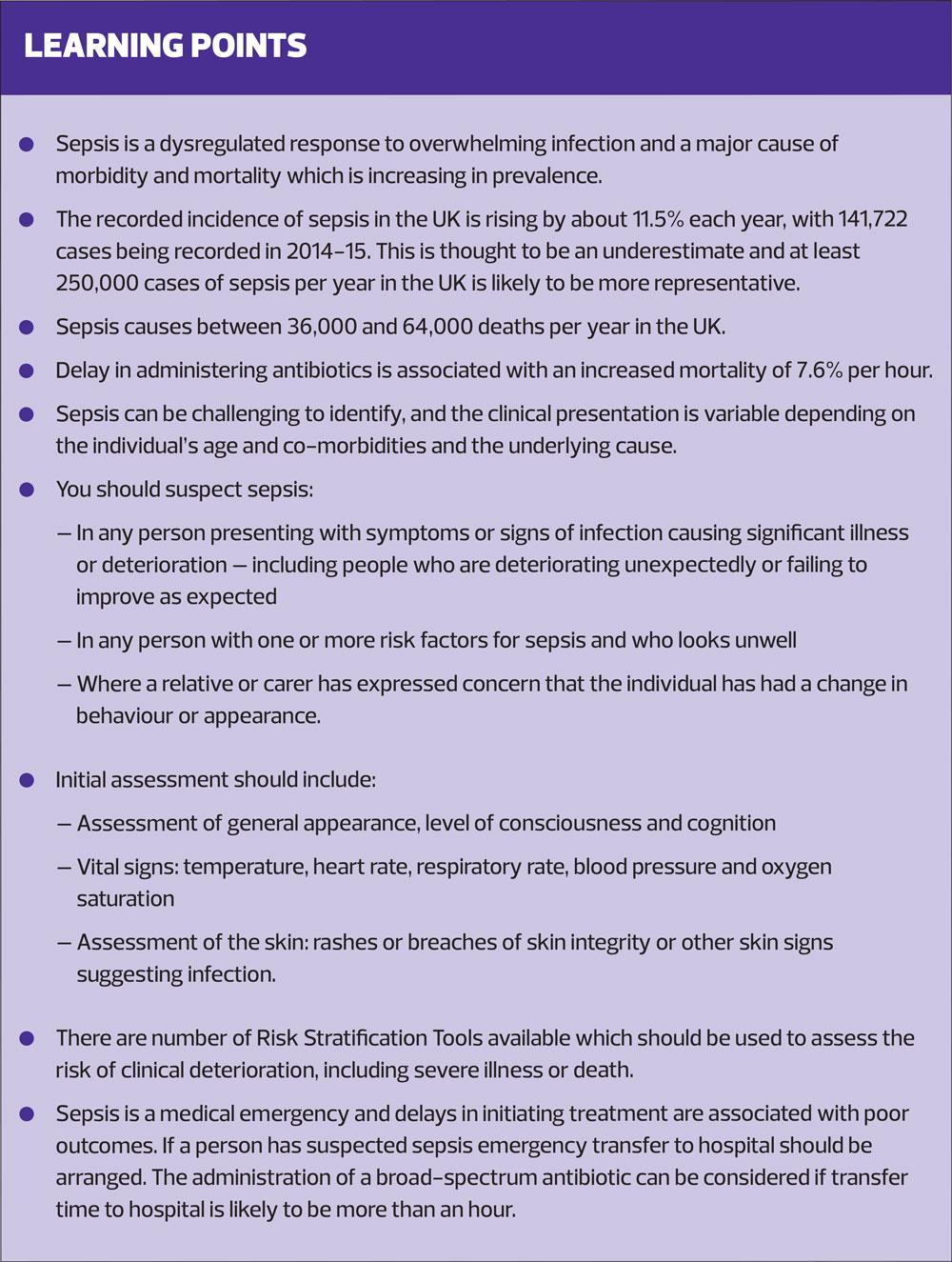

According to the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3), sepsis is a syndrome defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction due to a dysregulated response to infection.1 Septic shock is a subset of sepsis, which describes circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities, which are associated with a greater risk of mortality than sepsis alone.

INCIDENCE AND PROGNOSIS

The incidence of sepsis is increasing. This reflects an ageing population with multiple co-morbidities, increased use of immunosuppressive drugs, increased antibiotic resistance, and increased awareness of the diagnosis.2

The UK Sepsis Trust suggests the recorded incidence of sepsis is rising by about 11.5% each year, with 141,772 cases per year recorded in 2014–15. It notes that this is likely to be an underestimate of the true incidence, and suggests that an estimate of at least 250,000 cases of sepsis each year in the UK is more representative.2 It causes between 36,"Š000 and 64,"Š000 deaths annually in the UK. It has been estimated that a delay in administering antibiotics is associated with an increased mortality of 7.6% per hour.2

Organ dysfunction is an important predictor of prognosis, with multiple organ involvement being associated with a higher risk of mortality.3 Extremes of age and the presence of co-morbidities are also associated with a worse prognosis.2 A UK Sepsis Trust report cites an overall mortality rate in England of nearly 29%.2

Survivors of sepsis have higher rates of mortality following hospital discharge compared with other people and compared to non-sepsis admissions. Survivors have a greater risk of re-admission, with 30-day re-admission rates averaging between 19–32%.2 They may also have long-term physical, psychological, and cognitive impairments.1

Early suspicion of a diagnosis of sepsis combined with aggressive treatment is likely to reduce the rates of complications and death.4 For all practice nurses, recognition of the symptoms and signs of sepsis is therefore critically important.

SUSPECTING SEPSIS

Sepsis can be challenging to identify. The clinical presentation is variable depending on the underlying cause and the person's age and co-morbidities.5 You should suspect sepsis in any person presenting with:

- Symptoms or signs indicating possible infection causing significant illness or deterioration. This includes people who are deteriorating unexpectedly or failing to improve as expected

- One or more risk factors for sepsis, and who looks unwell

- Concern from a relative or carer that there is a change in appearance or behaviour.

Sepsis may result from infection with almost any pathogen; therefore, it may present with a wide range of clinical features depending on the site of infection and the potential response. You will need to bear in mind that people with sepsis may present with non-specific, non-localised clinical features, for example general malaise, agitation, or behavioural change. They may not present with a high temperature and may present with hypothermia.

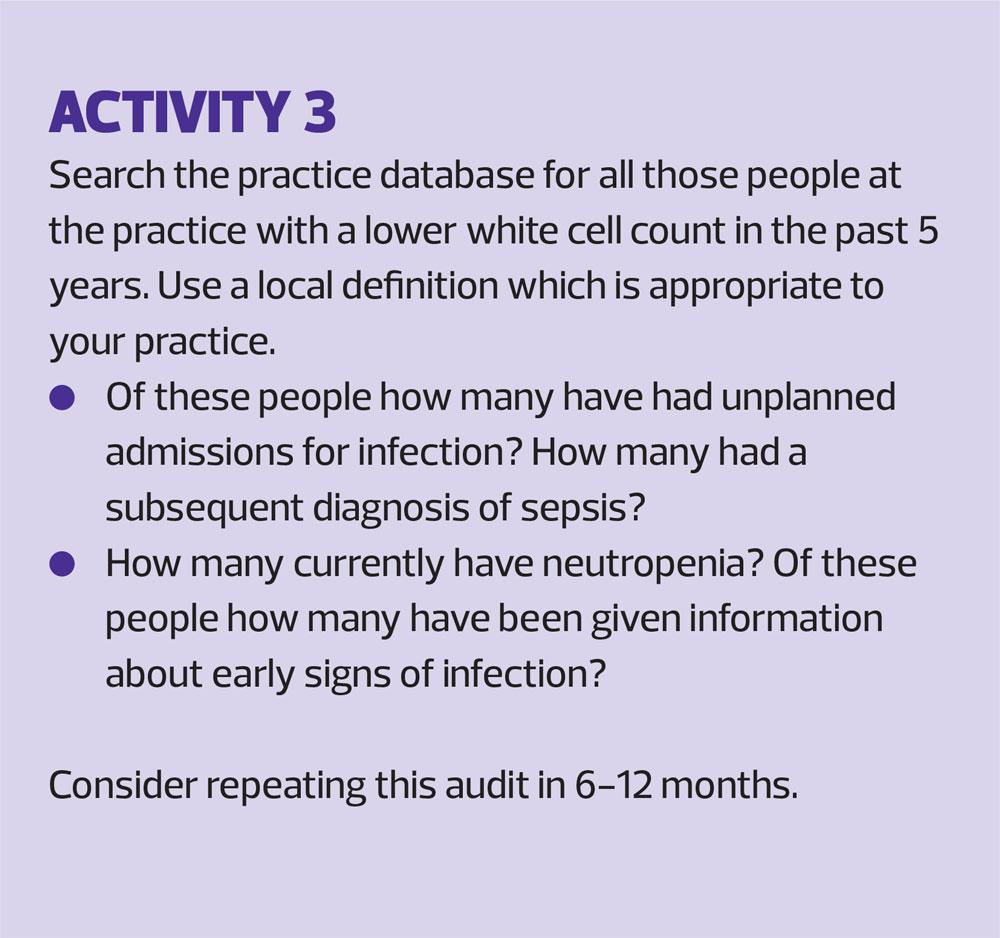

People receiving anticancer treatment are particularly vulnerable to neutropenic sepsis. (Neutropenia is defined an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5 x 109/L or lower.) You should suspect this diagnosis in any person receiving anticancer treatment who becomes unwell and they will need prompt and appropriate management.6

ASSESSMENT OF SUSPECTED SEPSIS

If a person with any infection presents with suspected sepsis, arrange urgent assessment to identify markers of increased risk of severe illness or death, so that they can be managed appropriately.5

History

Ask the person, and/or their carers about any history of recent fever or rigors. Ask about any symptoms that might suggest specific infection, such as dysuria or productive cough.

Sepsis can result in altered behaviour, mental state, or cognition, such as not responding normally to social cues or waking only with prolonged stimulation, or new irritability (in children) or new-onset confusion (in adults). It can also result in a sudden change or deterioration in the person’s functional ability

You will need to look for and ask about any clinical features suggesting dehydration, such as reduced urine output in the past 18 hours.

It is important to determine if there are any possible risk factors for sepsis present, such as co-morbidities and drug treatments. It is also important to determine if there are possible risk factors for antibiotic resistance, such as:

- Recent history of previous antibiotic therapy

- Previous hospital admissions

- Residency in a care home.

You will also need to determine the person’s immunisation status. This is particularly important in infants and young children.

Examination

Examination should start with an assessment of the individual’s general appearance, level of consciousness and cognition. This cognitive assessment should include recognition of new-onset confusion, disorientation, and/or agitation. In children under 5 years a weak, high-pitched, or continuous cry should raise your level of suspicion.

Record the vital signs, including temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation. You should measure blood pressure in children under 12 years with an appropriately sized cuff, and oxygen saturation should be measured at any age, with the proviso that taking these measurements does not result in a delay in specialist assessment and treatment.

Is the temperature raised or lowered? Fever is the most common presentation of sepsis. However, you should not use temperature as the sole predictor of sepsis and should not rely on fever or hypothermia to rule sepsis in or out.

Look for any signs of respiratory distress. In children under 5 years these include:

- Nasal flaring

- Grunting

- Apnoea.

Hypotension is a presenting feature in 40% of people with sepsis but be aware that a normal blood pressure does not exclude sepsis in children and young people.

Examine the skin. Look for mottling or an ashen appearance; pallor or cyanosis of the skin, lips or tongue; cold peripheries. A non-blanching rash may suggest meningococcal disease. Observe capillary refill time and oxygen saturation. Abnormal results may indicate poor peripheral perfusion. Look for any breach of skin integrity (e.g. cuts, burns, or skin infections) or other skin signs suggesting infection, such as erythema, swelling or discharge at a surgical site, or wound breakdown.

Are the mucous membranes dry or are there other signs of dehydration?

Your examination should also include looking for any signs of a possible, underlying source of infection.

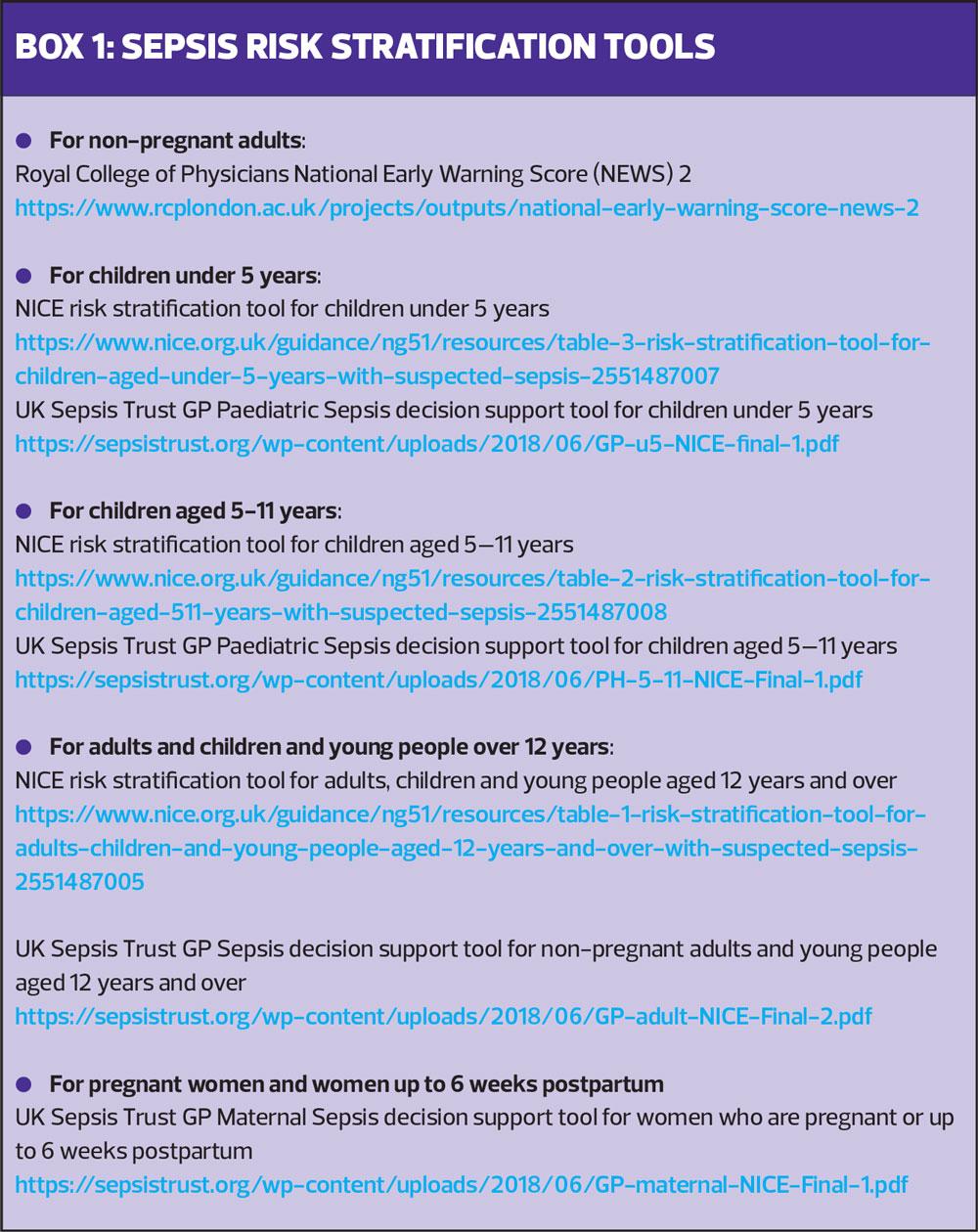

Risk stratification

Use a sepsis risk stratification tool to assess the risk of clinical deterioration, including severe illness or death from sepsis, depending on the person's age, risk factors, and clinical features of concern.7,8 Possible tools are listed in Box 1.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The list of alternative conditions that may present similarly to sepsis is long.5 These differential diagnoses include:

- Pulmonary embolism

- Acute myocardial infarction

- Heart failure

- Acute delirium

- Acute pancreatitis

- Diabetic ketoacidosis

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Acute blood loss and hypovolaemia

- Trauma and tissue injury, burns

- Drug reactions, including neuroleptic malignant syndrome (an idiosyncratic complication of antipsychotic drug use, characterized by hyperthermia, rigidity, sweating, and labile blood pressure)

- Intoxication and poisoning, including carbon monoxide poisoning.

MANAGEMENT AND ACTION

It is important to stress at this point that sepsis is a medical emergency. Delays in treatment are linked to poorer outcomes. If you are confronted by a person with suspected sepsis, depending on your assessment of their risk of clinical deterioration and your clinical judgement, you will need to arrange emergency transfer to hospital.5

If the person has suspected neutropenic sepsis, arrange immediate hospital assessment in secondary or tertiary care.6

If neutropenic sepsis is not suspected, you should pre-alert secondary care and arrange emergency transfer to hospital (usually by 999 ambulance),9,10 if:

- There are any high-risk criteria for severe illness or death from sepsis

- A child or young person is aged under 17 years, they are immunocompromised or immunosuppressed, and they have any moderate-to-high risk criteria

- There are any moderate-to-high risk criteria and the person does not have an identified underlying diagnosis or condition, and/or they cannot be safely treated in an out-of-hospital setting.

Management in primary care may be appropriate, even if you have assessed a person as being at high risk of severe illness or death from sepsis, if transfer to hospital would be inappropriate, e.g. if they are approaching the end of their life or if this situation is appropriately covered in their Advance Care Plan.

SUMMARY

Sepsis is a dysregulated response to overwhelming infection and a major cause of morbidity and mortality, and is increasing in prevalence. Early recognition and treatment are linked to improved outcomes for patients. However, the early signs of sepsis can be subtle and difficult to differentiate between other minor ailments. You will need to consider a possible diagnosis of sepsis and exercise an index of suspicion when dealing with any patient with infection. This is particularly important when dealing with vulnerable patients with long term conditions, multi-morbidity, and those on immunosuppressive therapies. Those who may be neutropenic are at highest risk.

Dealing with these patients is a medical emergency, where delays to treatments can worsen prognosis. Practice nurses, especially those working in out of hours settings, need to be alert to the possibility of people presenting with symptoms and signs of sepsis. You should be able to assess these people using the correct equipment, physiological parameters and risk stratification tools. Armed with this information you will be well-placed to make the most appropriate assessment and communicate this with the emergency services and secondary care clinicians where necessary.

REFERENCES

1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016; 315(8): 801-810.

2. Daniels R, McNamara G, Nutbeam T, et al. The Sepsis Manual 4th edn 2017 https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Sepsis_Manual_2017_final_v7.pdf

3. Cecconi M, Evans L, Levy M, et al. Sepsis and septic shock. Lancet 2018; 392(10141): 75-87.

4. NHS England. Improving outcomes for patients with sepsis: a cross-system action plan. 2015 https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Sepsis-Action-Plan-23.12.15-v1.pdf

5. NICE. Sepsis: recognition, assessment and early management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016 http://www.nice.org.uk

6. NICE. Neutropenic sepsis: prevention and management in people with cancer. Clinical guideline CG151. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2012 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg151/resources/neutropenic-sepsis-prevention-and-management-in-people-with-cancer-pdf-35109626262469

7. Royal College of General Practitioners. Sepsis: guidance for GPs. RCGP. 2018 https://www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/resources/toolkits/-/media/A9786B0548AA429C92098B988C5EBB2F

8. Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2. Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. RCP. 2017. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/national-early-warning-score-news-2

9. Gauer RL. Early recognition and management of sepsis in adults: the first six hours. Am Fam Physician 2013; 88(1): 44-53.

10. Keeley A, Hine P, Nsutebu E. The recognition and management of sepsis and septic shock: a guide for non-intensivists. Postgrad Med J 2017; 93(1104): 626-634. [Abstract]

Related articles

View all Articles