Managing type 2 diabetes in elderly patients: new recommendations

MANDY GALLOWAY

MANDY GALLOWAY

Editor, Practice Nurse

Although we are seeing an increasing incidence of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents, most people with diabetes are in their 60s or 70s, and their management needs to adapt to take account of their changing needs

New guidance developed by the University of Exeter Medical School in collaboration with NHS England, sets out a framework for the management of T2D in older people, aiming to reduce their risk of complications – particularly hypoglycaemia – and improving their quality of life.1

The guidance sets out less stringent targets for frail older adults who are at risk of over-treatment with glucose-lowering medications,2 recommendations for ‘de-prescribing’ – a process of withdrawing inappropriate medications – and reducing the risks of hypoglycaemia.

In younger people with diabetes, a formulaic approach to management can be very successful: targets, based on guideline recommendations, are set and treatment initiated and intensified to achieve and maintain blood glucose control. But Increasing numbers of people with T2D are living into their 70s and beyond.

The aim of ‘treating to target’ is to prevent the complications of diabetes: reducing HbA1c decreases the onset and progression of microvascular complications,3 such as retinopathy, but the impact on macrovascular complications, such as cardiovascular disease, may not be apparent until after many years of improved glycaemic control.4

Older patients have a different natural history of diabetes, partly due to shorter life expectancy, but also because they have greater incidence of comorbidity. The average number of comorbid conditions in people with diabetes is 3.5 – notably hypertension, musculosketal disease and depression/anxiety.5 They are therefore more likely to be taking more drugs – polypharmacy – and they are also at increased risk of adverse effects of treatment.1

Older adults do not have as many years of anticipated life expectancy and therefore may not benefit to the same degree as younger patients from aggressive treatment.1

Furthermore, we have had evidence for more than a decade that very intensive treatment may not always be beneficial.6 The ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) study showed that driving HbA1c levels down to below 42mmol/mol (6%) increased mortality from any cause by 22%, rather than – as might be expected – reducing death rates.6

All the major guidelines – NICE, SIGN, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) acknowledge the need for individualised care, but when it comes to target-setting, the range is quite narrow: 48 – 53mmol/mol. Although the Quality and Outcomes Framework7 target (the number of people on the register with an HbA1c of 59mmol/mol or less in the preceding 12 months) is less aggressive, it does add a financial pressure on general practice to ‘treat to target’. And once a target has been agreed, how often is it reviewed or amended in line with the individual patient’s circumstances?

However, an HbA1c target that is appropriate for a younger person, or someone who is newly diagnosed may be too stringent for an elderly patient, particularly if they are already showing signs of frailty.8

FRAILTY

Traditional micro- and macrovascular complications of diabetes account for less than half of the diabetes-related disability in older people.1 Both ageing and diabetes are risk factors for functional decline – a loss of mobility, ability to carry out activities of daily living and maintain independence – and disability.

Diabetes can lead to sarcopenia, a decline in muscle mass, strength and function.9 With increasing age, loss of muscle mass and increasing visceral fat occur, leading to increased insulin resistance. As insulin stimulates protein synthesis in the muscle, defects in insulin signalling compound the risk of developing muscle weakness and loss of muscle mass.10 Age-related inadequate nutrition and reduced physical exercise are further predisposing factors for poor muscle function.10

Frailty is defined as:

- A state of vulnerability that leads to a range of measurable adverse outcomes such as falls, or a decline in physical performance

- A decline in physiological reserve and the inability to resist physical or psychological stressors

- A pre-disability condition10

Overall, severe frailty affects 3% of the population aged 65 and over in England, for moderate frailty the prevalence is 12%, and for mild frailty the figure is 35%.11 But in older people with diabetes, frailty may be present in up to 48%.10

Frailty, now recognised as a major factor in the increased risk of death and disability, but the assessment of frailty does not form part of routine reviews for patients with diabetes.1

ASSESSING FRAILTY

A number of approaches are available to detect frailty in patients living in the community, which are also applicable to patients with diabetes.1 QOF supports the use of a validated tool such as the electronic Frailty Index (eFI), which is embedded in the main primary care computer systems, and uses a ‘cumulative deficit’ model, which measures frailty of the basis of clinical signs, symptoms, diseases, disabilities and abnormal test values.12 It uses existing data from the patient record, and is made up of 36 deficits over 2,000 Read codes. Another system in common use is the five-item FRAIL score.13 This assesses:

- Fatigue

- Resistance (difficulty walking upstairs)

- Ambulation

- Illness, and

- Loss of weight13

The assessment process in primary care would comprise clinical review, the eFI score, 4m gait speed and Get Up and Go test. A diagnosis of frailty should prompt referral to a diabetes specialist and/or geriatrician for further evaluation. Initial management should include:

- Positive lifestyle intervention and regular exercise

- Nutritional assessment and exclude vitamin D deficiency

- Review glucose control and medications according to functional status.1

TARGETS

There is growing recognition that intensive glucose-lowering treatment in T2D has limited benefits and may in fact be dangerous in older people.1 This should prompt clinicians to modify HbA1c targets in patients who are frail or who have limited life expectancy. This is not to say that there should be no targets at all: chronic hyperglycaemia has negative effects on quality of life, with osmotic diuresis leading to dehydration, impaired vision and decreased cognition.1

The targets suggested in this new guidance are currently consensus- rather than evidence-based because there is a lack of outcome data for individualised goal setting.

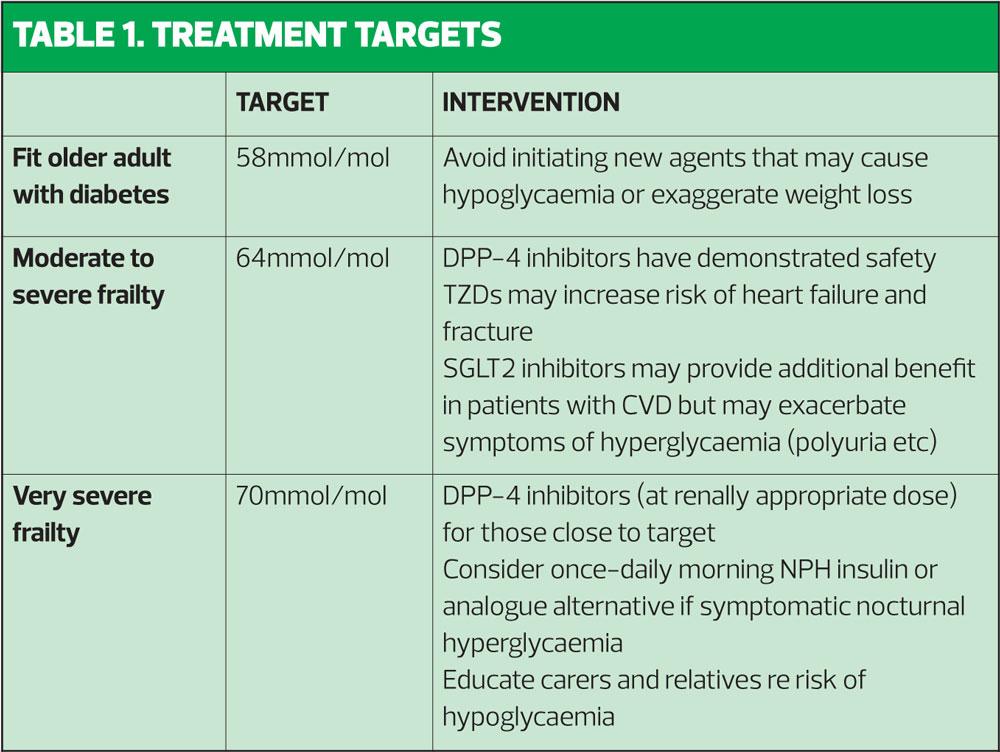

‘Biologically young’ older adults can be viewed in the same way as younger patients, and for these patients, a glycaemic target of 58mmol/mol remains standard.1

Very few people with diabetes aged >70 years can be expected to benefit from intensive treatment to targets below 53mmol/mol. HBA1c levels in excess of 64mmol/mol may be associated with increased hyperglycaemic symptoms of polyuria, polydipsia and nocturia – which may be particularly pertinent in older men who are often also experiencing the effects of benign prostatic hyperplasia – as well as increased risk of urinary infection, candidiasis and impaired response to systemic infections. There are no proven short-term benefits of achieving HbA1c levels below 59mmol/mol.1

As a result, the guidance proposes the following targets:

- For adults with mild to moderate frailty: ≤64mmol/mol.

- For the very frail, elderly patient: <70mmol/mol. (See Table 1)

DRUG TREATMENT

There is a paucity of studies of glucose-lowering in older patients with frailty and diabetes,10 and indeed most clinical trials routinely exclude subjects aged over 70: only 1.4% of clinical trials explicitly recruit older adults, and a still smaller proportion include patients who are frail.1

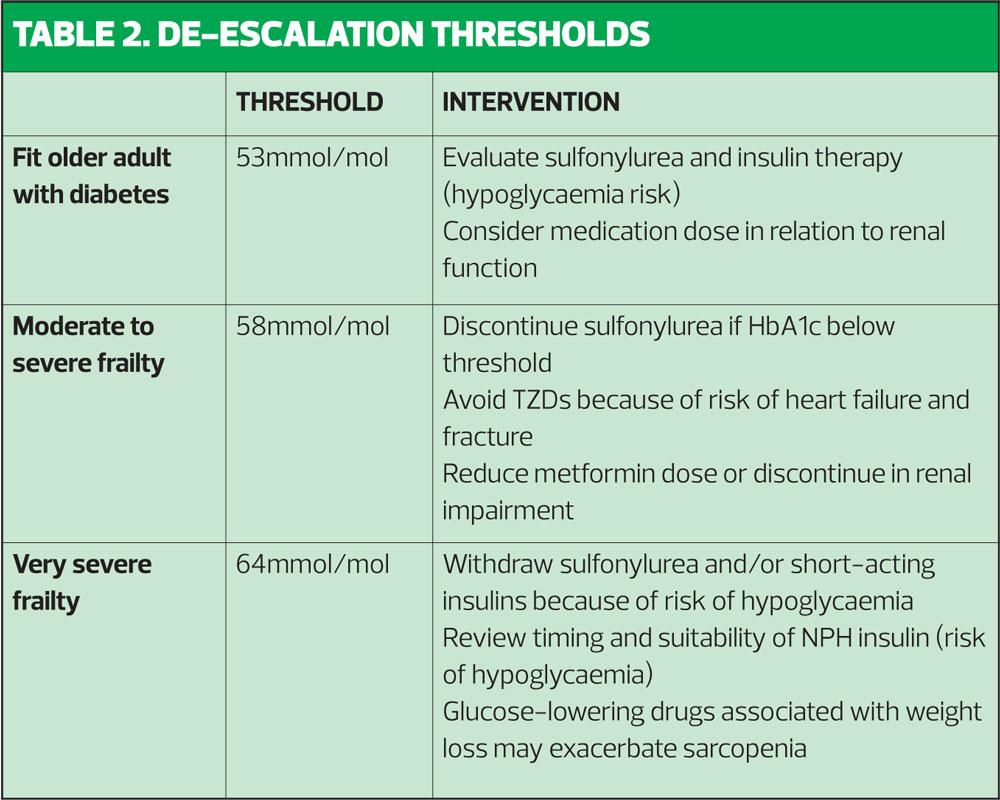

The guidance includes recommendations for ‘de-prescribing’ for frail, older patients who are at an increased risk of over-treatment with glucose-lowering medications.

Nonetheless, even in fit, elderly patients, practitioners should be aware of the risk of hypoglycaemia when adding in therapies. The guidance therefore cautions against the introduction of sulfonylureas or short-acting insulins.

For those with good glycaemic control, there isn’t necessarily a need for

de-escalation of their medication, unless there is evidence of over-treatment. Someone treated with metformin or a DPP-4 inhibitor, which are weight-neutral and have a low risk of hypoglycaemia, may not need their medication de-escalated or withdrawn – and lifestyle advice (particularly in respect of their diabetes, but also to prevent the development of frailty) should be continued.1

The choice of agents to achieve the above targets is limited.

Metformin is the logical choice given its low frequency of hypoglycaemia and good cardiovascular profile. However, it is contraindicated in up to 50% of frail or very frail elderly patients, who are likely to have a degree or renal impairment.

Sulfonylureas carry a risk of hypoglycaemia, which may persist for several hours – particularly with extended release formulations. Sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycaemia must always be treated in hospital.14 Furthermore, because they are an insulin secretagogue, their usefulness is limited in older patients with pancreatic beta-cell failure.1

DPP-4 inhibitors have a proven safety record even in the very frail, and have similar efficacy in older populations to that in younger patients.

Pioglitazone, a thiazolidinedione (TZD), can precipitate osteoporosis and carries an increased risk of fractures, and of heart failure. It should not be used in patients with heart failure or history of heart failure.15 Pioglitazone should also be avoided in patients with active bladder cancer, a past history of bladder cancer, or uninvestigated macroscopic haematuria, and should be used with caution in elderly patients as the risk of bladder cancer increases with age. Because TZDs can cause peripheral oedema in older patients, they may reduce mobility.1

GLP-1 agonists are incretin-based therapies that increase insulin secretion in response to increasing glucose levels, delay gastric emptying and suppress mealtime glucagon secretion. They have comparatively few adverse effects, but because they are associated with weight-loss, they may exacerbate frailty and contribute to the development of sarcopenia.1

SGLT-2 inhibitors work by increasing excretion of glucose in urine, and efficacy is dependent on adequate renal function, which – as previously noted – is frequently impaired in older patients. They are also associated with weight loss, which is not desirable in frail patients.1

So in terms of oral agents, the choice would appear to be metformin if renal function is not impaired, or DPP-4 inhibitors, which the guidance suggests may be a suitable option for those within 11mmol/mol of their treatment goal. If intensification is required, insulin becomes the logical choice.1

For the majority of frail adults, a simple approach of isophane insulin in the morning provides a modest peak in insulin availability after approximately 4 hours, with negligible activity overnight, minimising the risk of nocturnal hypoglycaemia – but increasing the likelihood of nocturia. Should nocturnal insulin be required, a once-daily regimen of long-acting analogue insulin may be associated with a lower risk of hyperglycaemia than twice-daily isophane insulin. The newer ultra-long acting analogue insulin degudec has been reported to lead to further reductions in severe and nocturnal hypoglycaemia but has not been studied in elderly, frail subjects.1

There is no evidence to support intensive management of prandial glucose so short-acting insulins should also be discontinued because of the significant risk of hypoglycaemia, unless there are active symptoms of postprandial hyperglycaemia. In such patients, a fast-acting insulin analogue can be prescribed as required after meals, based on postprandial glucose monitoring, to take account of the variable and unpredictable food intake when frailty is an issue.1

In the very frail, long-term protection ceases to be a concern, as the prognosis of the very frail is such that benefit is unlikely to be realised within anticipated lifespan. So at this stage, the recommendation is to review, and de-prescribe any treatment that does not improve the individual patient’s quality of life. The guidance recommends discontinuing oral therapy for any severely frail person with an HBA1c <64mmol/mol. Recommendations for treatment thresholds and de-escalation of therapy are shown in Table 2.

PATIENT ATTITUDES

A patient who has fastidiously adhered to their treatment regimen for years if not decades may find it difficult to adapt to being told to reduce or stop therapy, and this may increase disease-related anxiety.1 It is therefore important to allow sufficient time to explain the changing physiological demands of ageing and the increased risks of side effects from treatment.

It is also important to explain that a decision to establish less aggressive targets is not a decision ‘not to treat’.

CONCLUSION

The management of older people with diabetes is often inadequate and inappropriate because it fails to take account of the complexity of their condition and comorbidities, age-related physiology and the risk of iatrogenic adverse drug reactions.1 Older patients should be assessed for frailty as part of their annual review, and this should influence their future management in terms of treatment targets and choice of glucose-lowering medication.

REFERENCES

1. Strain WD, Hope SV, Green A, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in older people: a brief statement of key principles of modern day management including the assessment of frailty. A national collaborative stakeholder initiative. Diabetic Medicine. ePub 07 April 2018 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/dme.13644

2. Lipska KJ, Ross JS, Miao Y, et al. Potential overtreatment of diabetes mellitus in older adults with tight glycaemic control. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:356–362

3. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: Update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015;38:140–149

4. Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, et al. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1577–895.

5. Cassell A, Edwards D, Harshfield A, et al. The epidemiology of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2018; bjgp 18X695465. http://bjgp.org/content/early/2018/03/12/bjgp18X695465

6. ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2545–59

7. NHS Employers. Summary of changes to QOF 2017/18 – England. https://www.nhsemployers.org/-/media/Employers/Documents/Primary-care-contracts/QOF/2017-18/201718-Quality-and-outcomes-framework-summary-of-changes.pdf

8. Downey J. The importance of achieving target HBA1c in the early years. Practice Nurse 2018;48(1):12–16

9. Sinclair AJ, Abdelhafiz AH, Rodriguez-Manas L. Frailty and sarcopenia – newly emerging and high impact complications of diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2017;31:1465–1473

10. Sinclair AJ, Abdelhafiz A, Dunning T, et al. An international position statement on the management of frailty in diabetes mellitus: summary of recommendations 2017. J Frailty Aging 2018;7:10–20

11. NHS England. Toolkit for general practice in supporting older people living with frailty, 2014 (Updated 2017). https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/toolkit-general-practice-frailty.pdf

12. Improvement Academy Yorkshire & Humber AHSN. Electronic Frailty Index Guidance Notes. http://www.improvementacademy.org/documents/Projects/

healthy_ageing/eFI%20Guidance%20SystmOne%20Notes%20for%20HAC%20Partners.pdf

13. Malmstrom TK, Miller DK, Morley JE. A comparison of four frailty models. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:721–6

14. BNF. Gliclazide. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/gliclazide.html

15. BNF. Pioglitazone. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/pioglitazone.html

Related articles

View all Articles