Evidence-based approaches to preventing type 2 diabetes

Beverley Bostock

Beverley Bostock

RGN MSc MA QN

Advanced Nurse Practitioner,

Mann Cottage Surgery, Gloucestershire

Council Member,

Primary Care Cardiovascular Society

Practice Nurse 2023;53(3):20-24

There is mounting evidence that the right approach can prevent the development of type 2 diabetes in those at risk, so it is vital to identify these individuals and be aware of effective interventions

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is associated with central obesity and approximately 90% of people diagnosed with T2D are overweight or obese.1 Central obesity is known to drive insulin resistance, hypertension and dyslipidaemia, all of which are implicated in the development of the cardiovascular complications of T2D.2 These complications include diabetic nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke and peripheral arterial disease which can impact on the quality and quantity of years lived. The cost of treating these complications makes up the majority proportion of the overall cost to the NHS of managing diabetes.3 Prevention of T2D therefore offers significant advantages for individuals, the NHS and society in general.

THE LINK BETWEEN OBESITY, NDH AND TYPE 2 DIABETES

Obesity has been recognised as a disorder of energy homeostasis which has complex hormonal and behavioural causes and which requires a multifaceted approach to management.4 Furthermore, it is linked to insulin resistance which not only raises blood glucose levels (resulting in both non diabetic hyperglycaemia [NDH] and T2D) but also leads to hypertension and dyslipidaemia. This is often referred to as metabolic syndrome, which in itself increases the risk of cardiovascular disease.5 Vascular fibrosis and stiffness have also been seen in people with insulin resistance.5 People with NDH have been shown to develop CV complications even before they develop T2D.6

People who are at risk of developing T2D include those with a raised body mass index (BMI), based on ethnically adjusted values, those with unhealthy eating habits specifically involving a high intake of processed foods, low activity levels with high sedentary time, smoking and hypertension.7 Identifying these individuals before they are diagnosed with T2D (and ideally proactively managing these risk factors even before they develop NDH) is critical if the NHS is going to reduce the impact of T2D and its complications on society. On that basis, people with increased cardiovascular risk scores (e.g., via QRisk3™) and people with other long-term conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) could be targeted for assessment of their risk of T2D through risk assessment tools and blood tests. Tools which have been specifically designed to identify those at risk of T2D include QDiabetes (https://qdiabetes.org/) and the Diabetes UK tool (https://www.diabetes.org.uk/preventing-type-2-diabetes/diabetes-risk-factors).

NDH, or pre-diabetes, is diagnosed if the HbA1c is 42-47mmol/mol, with T2D being diagnosed if the HbA1c is over 48mmol/mol on (usually) two occasions within 2 weeks.

The prevention of T2D is primarily achieved through identifying those at increased risk and supporting them to implement lifestyle interventions, which promote weight loss.8

EVIDENCE-BASED INTERVENTIONS FOR THE PREVENTION OF DIABETES

A meta-analysis and systematic review by Glechner et al (2018) confirmed the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in reducing the progression from pre-diabetes (NDH) to T2D.9 In people with NDH, a weight loss of just 5-7% has been shown to reduce the risk of developing T2D and improve cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure and dyslipidaemia.10 In early evaluations of the Diabetes Prevention Program, a reduction of 58% in the incidence of diabetes was recorded through a combined approach of dietary changes and increased physical activity, although the level of risk reduction could be as high as 70%.11,12

Consideration should be given as to how weight loss might be achieved. NICE recommends that a tailored, flexible and individual approach to weight management should be taken.13 The DiRECT study demonstrated that very low calorie diets (VLCDs) can help people to achieve remission of T2D in people who are already diagnosed, although there is limited evidence for their use in NDH.14 Nonetheless, results from an extension of the original study showed that 23% of those people who were in remission at two years, remained in remission after five years – see https://www.ncl.ac.uk/press/articles/latest/2023/04/type2diabetesintoremissionfor5years/

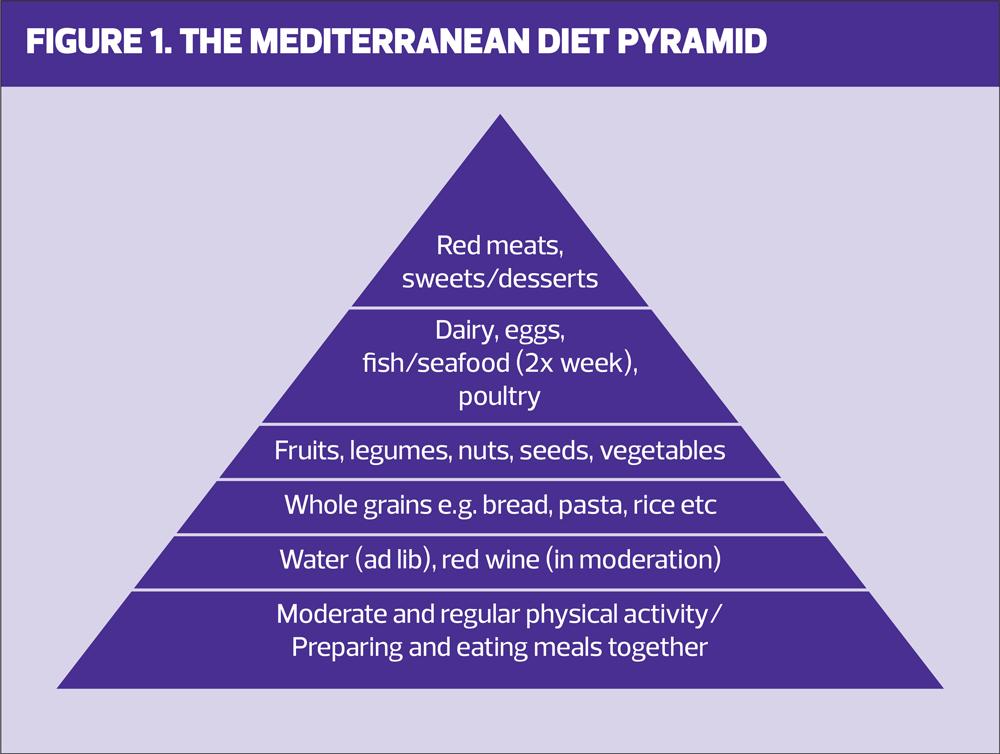

There is also some evidence to suggest that carbohydrate restriction can help to reduce weight and HbA1c levels.15 Intermittent fasting and time limited eating also have a developing evidence base for weight loss and reducing insulin resistance.16 The Seven Countries Study and other trials have demonstrated the benefits of the Mediterranean diet in the prevention and management of conditions such as cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. This approach is summarised in the Mediterranean Pyramid diagram (Figure 1), which can be used as a starting point for discussions with patients about sustainable (in terms of longevity and the environment) approaches to weight loss and long-term weight management.17

Pharmacological interventions can also help to prevent diabetes. Metformin is licensed for NDH but there are arguments against using it this way, including the fact that not everyone with NDH will go on to develop T2D.18 GLP-1 RA drugs also support weight loss and are not associated with a risk of hypoglycaemia. However, only liraglutide and semaglutide are currently licensed for weight loss in the absence of T2D. Tirzepatide is a GLP-1 RA/GIP drug which is currently licensed to treat T2D but which has also shown significant reductions in weight.19 In the SURPASS studies,1-5 21-68% lost more than 10% of their baseline body weight.19 This is ready to launch in the UK, but supplies are already low and again, it will be licensed for T2D only, initially.

Increasing physical activity levels can support dietary interventions to produce a calorie deficit, but according to recent data, less than two thirds of people in England aged 16 and over actually achieve the recommended 150 minutes or more of moderate intensity physical activity a week. Exercise has also been shown to offer additional benefits in terms of improved mitochondrial function, oxidisation of fatty acids and lowering of blood pressure, insulin resistance and inflammation.19 Various studies have confirmed the benefits of physical activity on systolic blood pressure and the levels and functionality of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and triglycerides.20,21 This is important as hypertension and dyslipidaemia often conspire with hyperglycaemia to cause microvascular and macrovascular damage.

In the Studies of a Targeted Risk Reduction Intervention through Defined Exercise (STRRIDE) trial, which focused on people with NDH, adding resistance to aerobic training improved insulin sensitivity and reduced the likelihood of participants developing T2D, with the best results being seen when dietary changes were combined with aerobic exercise.22

This range of dietary, activity and pharmacological options highlights the need for an individualised approach, based on personal choice. Consideration also needs to be given to whether people have access to low-cost healthy foods, and whether their environment is conducive to them being physically active.

BEHAVIOUR CHANGE THROUGH MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING

In spite of the evidence for lifestyle changes in the prevention of diabetes, there are many barriers to change, and these will be different from individual to individual. Skoglund et al identified key barriers that can prevent behaviour change, including the individual’s perception of the importance of change, difficulties maintaining changes and challenges finding adequate support in order to initiate and maintain these changes.23 General practice nurses (GPNs) can help people to overcome some of these barriers by providing psychological and practical support. Behaviour change consultation skills can help people to identify the need for change, why they want to change and how they can become more confident that change is possible. A simple way to start the conversation is to ask people how important it is to make lifestyle changes on a scale of 0-10 and then ask them how confident they are that they can make them on the same scale of 0-10. The skill is in moving them up the scale, particularly with respect to their confidence. A more recent approach to prompting people to make better choices is Nudge Theory, which uses choice architecture to subtly influence health behaviours.24

THE ROLE OF THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM IN THE PREVENTION OF T2D

Preventative care is the remit of everyone working in health and social care. Reception staff, GPs and GPNs, community and clinical pharmacists and healthcare assistants all play an important role in supporting people to live healthier lives. When it comes to the prevention of T2D, GPNs can help people to recognise their individual risk of developing diabetes and encourage engagement in behaviour change which can lead to risk reduction.

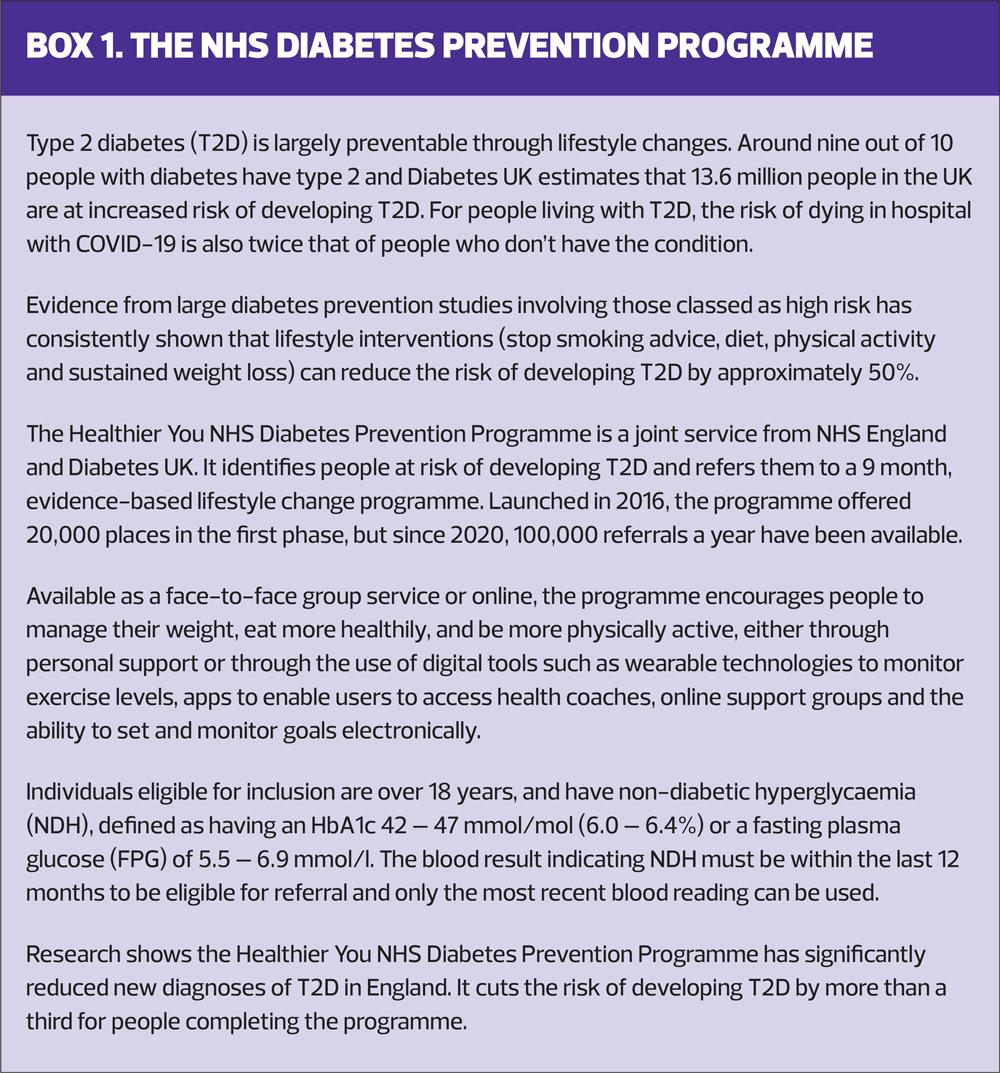

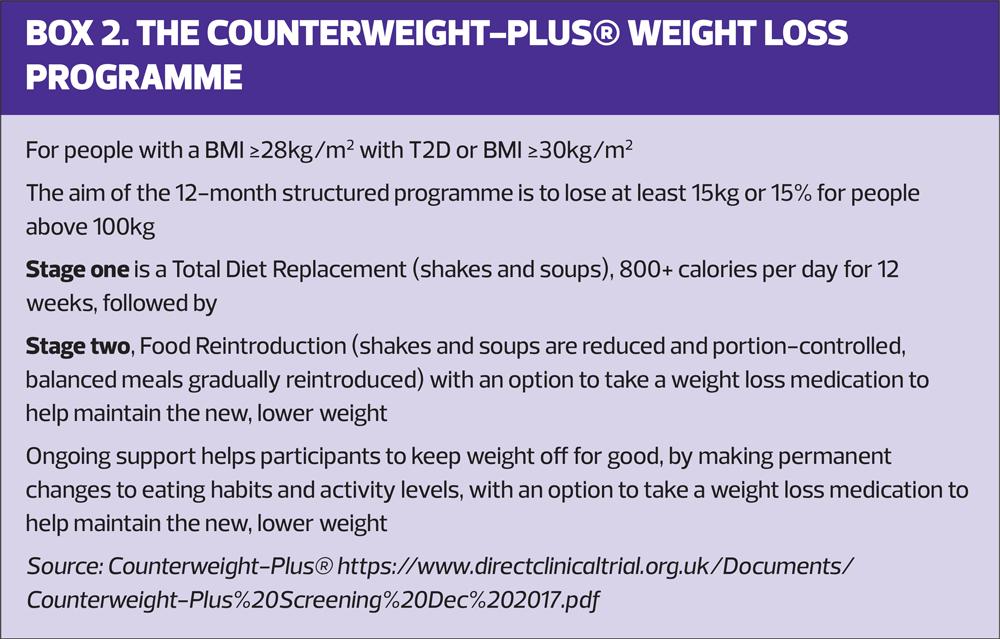

In Scotland, the ‘Diabetes My Way’ diabetes prevention programme can be accessed online via https://mydiabetesmyway.scot.nhs.uk/diabetes-prevention/. In Wales there is the All Wales Diabetes Prevention Programme: https://phw.nhs.wales/services-and-teams/primary-care-division/all-wales-diabetes-prevention-programme/ and in Northern Ireland, there is the Diabetes Prevention Programme: https://www.familysupportni.gov.uk/Service/7206/health-and-wellbeing/diabetes-prevention-programme--northern-ireland. In England, the National Diabetes Prevention Programme (NDPP) offers online and face to face courses based on lifestyle interventions which can reduce the risk of T2D. However, low uptake and long-term engagement has been a concern.25 In some areas of the country, people can be referred to commercial weight loss organisations and exercise programmes. The NHS has endorsed programmes such as Counterweight: https://www.counterweight.org/ and Slimming World. The DiRECT and DiRECT Extension studies used the Counterweight-Plus® weight management programme (see Box 2), initially delivered face-to-face in NHS primary care, but now adapted for remote/digital delivery. Other programmes which follow the ‘DiRECT Principles’ are likely to be similarly effective. The NHS Digital Weight Management Programme can also support people living with obesity and who also have diabetes and/or hypertension to manage their weight through a 12-week online behavioural and lifestyle programme: https://www.england.nhs.uk/digital-weight-management/. GPNs should therefore be aware of what is available both nationally and in their locality so that they can encourage people to consider what might work best for them.

Local Health and Wellbeing (HWB) teams can also be invaluable, using techniques such as motivational interviewing to improve engagement with lifestyle changes. Social prescribers can also support people with specific concerns, for example about how to manage finances to facilitate healthier eating on a budget. In some areas, members of the HWB team have linked up with food banks to offer support to people using this resource.

CONCLUSION

T2D is becoming a global concern with risks to health and the economy. With an NHS that is under unsustainable pressure, steps are urgently needed to reduce the impact of this condition, not least with regard to the associated cardiorenal complications, which bear a heavy cost in both human and financial terms. By recognising the impact of unhealthy lifestyles on the risk of developing pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes, clinicians and others have the capacity to support people to reduce their risk through education on healthy eating, increasing physical activity and smoking cessation. For those individuals who are thought to be at increased risk, measuring their HbA1c can help to confirm the diagnosis of pre-diabetes and T2D and can also reflect changes that the individual makes.

REFERENCES

1. International Diabetes Federation. Type 2 Diabetes; 2020 https://www.idf.org/aboutdiabetes/type-2-diabetes.html

2. Castro AV, Kolka CM, Kim SP, Bergman RN. Obesity, insulin resistance and comorbidities? Mechanisms of association. Arquivos brasileiros de endocrinologia e metabologia 2014;58(6): 600–609. https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-2730000003223

3. Andersson E, Persson S, Hallén N, et al. Costs of diabetes complications: hospital-based care and absence from work for 392,200 people with type 2 diabetes and matched control participants in Sweden. Diabetologia 2000;63(12):2582–2594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05277-3

4. Ghanemi A, Yoshioka M, St-Amand J. Broken energy homeostasis and obesity pathogenesis: the surrounding concepts. J Clin Med 2018;7(11):453. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7110453

5. Hill MA, Yang Y, Zhang L, et al. Insulin resistance, cardiovascular stiffening and cardiovascular disease. Metab Clin Exp 2021;119:154766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154766

6. Brannick B, Dagogo-Jack S. (2018). Prediabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: Pathophysiology and Interventions for Prevention and Risk Reduction. Endocrinol Metab Clin 2018;47(1):33–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2017.10.001

7. Bellou V, Belbasis L, Tzoulaki I, Evangelou E. Risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus: An exposure-wide umbrella review of meta-analyses. PloS one 2018;13(3):e0194127. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194127

8. Armato JP, DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani M, Ruby RJ. Successful treatment of prediabetes in clinical practice using physiological assessment (STOP DIABETES). Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6(10):781–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30234-1

9. Glechner A, Keuchel L, Affengruber L, et al. (2018). Effects of lifestyle changes on adults with prediabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Primary care diabetes 2018;12(5):393–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2018.07.003

10. Kucera M, Marchewka T, Craib A. Does losing 5-7% of prediabetic body weight from a diabetes prevention program decrease cardiovascular risks?. Spartan Med Res 2021;6(2):27627. https://doi.org/10.51894/001c.27627

11. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al, for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group (2002). Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. New Engl J Med 2002;346(6):393–403. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa012512

12. Forouhi NG, Luan J, Hennings S, Wareham NJ. Incidence of Type 2 diabetes in England and its association with baseline impaired fasting glucose: the Ely study 1990-2000. Diabetic medicine 2007;24(2):200–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02068.x

13. NICE CG189. Obesity: identification, assessment and management; 2014 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg189

14. Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2018;391(10120):541–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33102-1

15. Hafez Griauzde D, Saslow L, Patterson K, et al. Mixed methods pilot study of a low-carbohydrate diabetes prevention programme among adults with pre-diabetes in the USA. BMJ Open 2020;10(1):e033397. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033397

16. Xang BY, He LX, Xue L. (2022). Intermittent fasting: potential bridge of obesity and diabetes to health? Nutrients 2022;14(5):981. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14050981

17. Dominguez LJ, Di Bella G, Veronese N, Barbagallo M. Impact of Mediterranean Diet on Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and Longevity. Nutrients 2021;13(6):2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13062028

18. Davidson MB. (2020). Metformin should not be used to treat prediabetes. Diabetes Care 2020;43(9):1983–1987. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-2221

19. Nauck MA, D'Alessio DA. Tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor co-agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes with unmatched effectiveness regrading glycaemic control and body weight reduction. Cardiovascular diabetology 2022;21(1):169. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01604-7

20. Naci H, Salcher-Konrad M, Dias S, et al. How does exercise treatment compare with antihypertensive medications? A network meta-analysis of 391 randomised controlled trials assessing exercise and medication effects on systolic blood pressure. Br J Sports Med 2019;53(14):859–869. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099921

21. Ruiz-Ramie JJ, Barber JL, Sarzynski MA. (2019). Effects of exercise on HDL functionality. Current Opin Lipidol 2019;30(1):16–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOL.0000000000000568

22. Ross LM, Slentz CA, Zidek AM, et al. Effects of Amount, Intensity, and Mode of Exercise Training on Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes Risk in the STRRIDE Randomized Trials. Front Physiol 2021;12:626142. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.626142

23. Skoglund G, Nilsson BB, Olsen CF, et al. Facilitators and barriers for lifestyle change in people with prediabetes: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Public Health 2022;22(1):553. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12885-8

24. Kwan YH, Cheng TY, Yoon S, et al. (2020). A systematic review of nudge theories and strategies used to influence adult health behaviour and outcome in diabetes management. Diabetes Metab 2020;46(6):450–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2020.04.002

25. Whelan M, Bell L. The English National Health Service diabetes prevention programme (NHS DPP): A scoping review of existing evidence. Diabetic Medicine 2022;39(7):e14855

Related articles

View all Articles