Diabetic foot problems

MANDY GALLOWAY

MANDY GALLOWAY

Editor

Practice Nurse 2020;50(9):20

Around 64,000 people with diabetes at any one time are thought to have a diabetic foot ulcer, and every year there are around 7,000 minor (below the ankle) and major (above the ankle) amputations in people with diabetes.1 But with meticulous foot care and regular assessment many of these could be prevented.

Diabetic foot disease accounts for approximately 1% of the total NHS budget – aside from the personal costs of reduced mobility and sickness absence.1 Developing a diabetic foot ulcer has serious implications for mortality: only three in five people with diabetes who have had a diabetic foot ulcer survive for five years, dropping to half for those having a major amputation.1

According to the National Diabetes Foot Care Audit, one in three patients with severe ulcers had a foot disease-related admission within 6 months of their first expert assessment, and one in ten will have died within 1 year.1

People with diabetes develop foot ulcers because of neuropathy, ischaemia or both.2 An ulcer may arise as a result of trauma (injury, burns or scalds) or from repetitive, mechanical stress. The most common cause is accidental trauma, especially from ill-fitting footwear.2

More than 60% are the result of underlying neuropathy: hyperglycaemia induces metabolic abnormalities including the accumulation of sorbitol and fructose in the nerve cells, and a reduction in normal neuron conduction. Hyperglycaemia and oxidative stress also contribute to further nerve dysfunction and ischaemia. Damage to the nerves in the foot muscles cause an imbalance between flexion and extension of the affected foot, ultimately producing anatomic foot deformities, such as abnormal bony prominences and pressure points.3

Loss of sensation exacerbates the development of ulceration: wounds may go unnoticed and progressively worsen.3

Once the skin is broken, bacterial infection, tissue ischaemia, continuing trauma, and poor management contribute to defective healing.2

However, most serious foot problems can be prevented. The risk of developing a diabetic foot problem should be assessed when diabetes is diagnosed, at least annually thereafter, if any foot problems arise, and if the patient is admitted to hospital.4

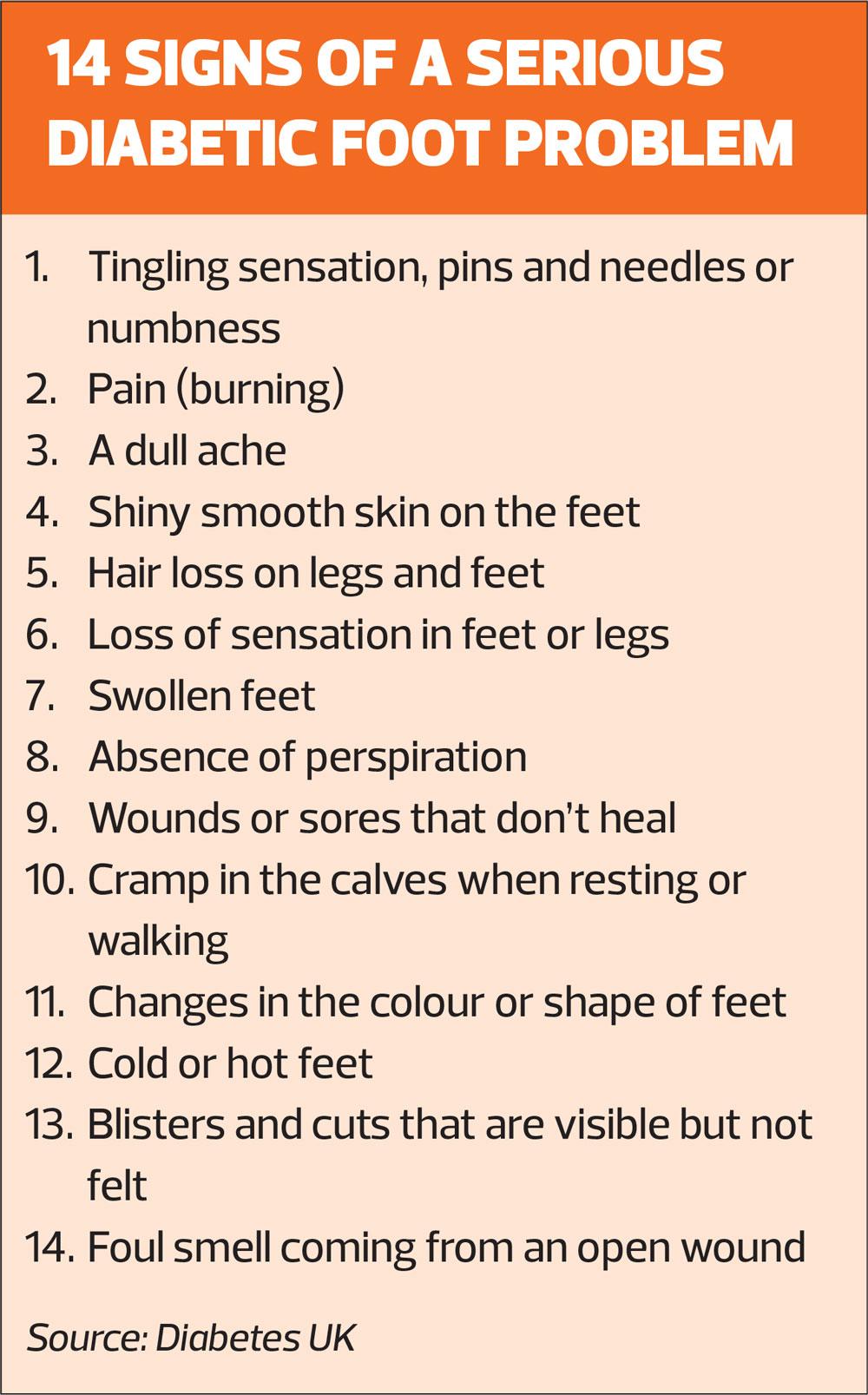

When examining the feet of a person with diabetes, examine both feet for evidence of risk factors:4

- Neuropathy (use a 10 g monofilament as part of sensory examination)

- Limb ischaemia (femoral, popliteal and foot pulses, ankle brachial pressure index)

- Callus

- Infection and/or inflammation

- Deformity

- Gangrene

- Charcot arthropathy

Assess risk – see Upskilling healthcare assistants in this issue. If the person has an ulcer, assess and document its size, depth and position. Use a standardised system to document severity, such as SINBAD (Site, Ischaemia, Neuropathy, Bacterial infection, Area and Depth).2

If a patient has a limb-threatening or life-threatening diabetic foot problem, refer immediately to acute services and inform the multidisciplinary foot care service. Examples include:

- Ulceration with fever or any signs of sepsis

- Ulceration with limb ischaemia

- Clinical concern that there is a deep-seated soft tissue or bone infection (with or without ulceration)

- Gangrene (with or without ulceration)2

REFERENCES

1. National Diabetes Foot Care Audit 4th annual report; April 2015 – March 2018. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/FC/18ED7F/NDFA%204AR%20-%20Main%20Report%20v1.1.pdf

2. Tidy C. Diabetic foot; 2016. https://patient.info/doctor/diabetic-foot

3. Clayton W, Elasy TA. A review of the pathophysiology, classification and treatment of foot ulcers in diabetic patients. Clinical Diabetes 2009;27(2):52-58

4. NICE NG19. Diabetic foot problems: prevention and management; 2015 (updated 2019). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng19/

Related articles

View all Articles