Rosacea: from evidence to competence

Isabel Lavers

Isabel Lavers

RGN BSc INP

Dermatology Nurse Specialist

Salford Royal NHS Trust Foundation Trust

Prescription Division, Galderma UK & Ireland Ltd

Conflict of Interest: Isabel Lavers is employed by Galderma UK; however, this article was written in the capacity of her clinical role, working for Salford Royal NHS Trust Foundation trust. This article has not been endorsed by Galderma UK.

Rosacea is one of the most common skin diseases in adulthood, and as in all conditions affecting the patient’s appearance, can cause considerable psychological distress. There is no cure, but with a careful combination of treatment strategies, it can be well-managed

Rosacea is a chronic condition which tends to affect the cheeks, forehead, chin and nose, and is characterised by erythema (redness), dilated blood vessels, small red bumps and pus-filled spots, often with a tendency to blush easily. It can also cause inflammation of the eye and eyelid.1 In the UK about 4,000–5,000 new cases of rosacea are diagnosed each year.2 It predominantly occurs in middle-aged and fair-skinned people and although common in women it tends to be more severe in men.3 The disorder is categorised into four subtypes, and treatment aims to manage and alleviate symptoms, as there is no cure for this condition. Rosacea often causes considerable psychological distress to those affected.4 This article will look at the pathogenesis, clinical features, diagnosis, trigger factors and psychosocial complications of rosacea, followed by a discussion of the most recent oral and topical antibiotic therapies and routine skin care.

Erythema, telangiectasia, papules, pustules and oedema of the face: patients with rosacea can suffer greatly due to their appearance. The condition is often trivialised and patients are often told that this is something they ‘must live with’. But this argument is poor and through careful combination of different treatment strategies this condition can be managed well.

Rosacea is a highly prevalent chronic inflammatory disorder of the skin, primarily affecting the central face (cheeks, chin, nose and forehead). Rosacea usually first presents between the age of 30-50 years, but precursors, in particular sudden reddening, are often already noticeable. It occurs at equal rates for both sexes and most commonly affects people with Celtic skin type and a fair complexion. Remissions and exacerbations are typical for this condition. Rosacea is broadly categorised into 4 subtypes, each presenting with its own set of symptoms and treatment options. Rosacea is a very visible condition and can cause high levels of psychological distress for those affected, as their red face is often assumed to be implicated with alcohol abuse.5 Patients may experience stress, social phobia, embarrassment and low self-esteem more than healthy individuals, resulting in social and professional isolation.6 Since the pathogenesis of rosacea is still poorly understood and there is no cure for the disease, treatment aims to manage disease symptoms, rather than target underlying causes. Management strategies should be tailored to alleviate the individual’s presenting symptoms and improve the patient’s quality of life. This requires the prescriber to have a detailed understanding of the rosacea treatments available and their therapeutic actions. Correct interpretation of current guidelines and an approach that identifies and meets the patient’s dermatological and psychological needs is the key to successful management of this long-term condition.

PATHOGENESIS

Rosacea usually starts with a tendency to flush easily, with the redness becoming more permanent over time. Chronic inflammation appears to play a key role in the pathophysiology of rosacea. The precise aetiology of rosacea remains largely unknown but is thought to be multifactorial. Factors include:7

- Defects of the congenital immune system triggering an increased non-specific defence against perceived skin surface pathogens, causing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and triggering symptoms associated with rosacea (inflammation, oedema and blood vessel growth)

- Hypersensitivity to physiological stimuli like spicy food, alcohol consumption and exposure to extremes in temperature, causing the typical red flushing seen in patients with rosacea

- An increased expression of toll like receptor 2 (TLR2) causing inflammatory reactions

One potential trigger for TLR2 activation, found to colonise the skin of patients with rosacea in significantly higher numbers than in healthy individuals and shown to trigger specific IgG antibody production, is the mite Demodex, which is thought to contribute to the inflammatory response in patients with rosacea.8 A reduction of Demodex colonisation has shown to decrease levels of inflammation.9 Bacterial infection is not thought to be a contributing factor in rosacea despite the presence of papules and pustules, commonly seen in subtypes II and III, which seem to be the result of chronic inflammation, due to innate immunity.7,10

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Statistics of prevalence differ, but it is thought that many cases of rosacea simply go undiagnosed. One UK study reported an incidence of 1.65 per 1000 population.2 Women tend to develop the disease from age 35 onward and men from about 50 years. In the under 30s population rosacea is rare and children are very rarely affected. Rosacea is most common in people with fair skin.

QUALITY OF LIFE

Rosacea is known to have a significant psychological and social impact, affecting the way patients feel about themselves, how they socially interact with and the way they are perceived by others. According to surveys by the National Rosacea Society, more than 76% of rosacea patients reported lowered self-confidence and self-esteem, and 41% said it had caused them to avoid public contact or cancel social engagements.11 For 88% of patients with severe rosacea, the disorder had adversely affected their professional interactions, and 51% said they had missed work because of their condition. Rosacea can be socially stigmatising since facial flushing, persistent erythema and broken vessels are often mistaken for alcohol abuse.5 Consequent embarrassment, low mood and self-esteem can result in social and professional withdrawal. The individual’s perception of their rosacea severity and their quality of life can differ from patient to patient, and may not directly related to severity and extent of the disease. This should be considered by healthcare professionals making the assessment and be reflected in prescribing decisions, involving the patient at each stage.

TRIGGER FACTORS

In addition to medical therapy, rosacea patients can improve their chances of maintaining remission by identifying and avoiding lifestyle and environmental factors that may trigger flare-ups or aggravate their individual condition. Many factors can trigger the flare-up or worsening of symptoms. Identifying these factors is an individual process because what causes a flare-up for one person may have no effect on another. Figure 1 shows a list of common rosacea trigger factors, taken from a survey of 1,066 rosacea patients.12 The list is not conclusive, so patients are encouraged to keep a diary of daily activities or events and relate them to any flare-ups they may experience.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION & DIAGNOSIS

In the majority of cases rosacea is diagnosed easily and based on clinical findings, usually based on patient demographics, distribution of lesions, appearance of symptoms and clinical findings on the day, with the exception of ocular rosacea, which is often not recognised by the clinician and therefore missed as a diagnosis. There is no confirmatory laboratory test. Biopsy is warranted only to rule out alternative diagnoses. A spectrum of primary and secondary symptoms can be observed in the patient with rosacea. (Box 1) Once rosacea is diagnosed, patients should be reassured of the benign, but chronic, nature of the condition. Counselling should be directed toward the identification and avoidance of triggers, diligent photo-protection, concealing cosmetics and proper skin care. As rosacea can have a profound effect on the patient’s self-esteem it is important that the patient is involved in every aspect of the treatment if their quality of life is to be enhanced.13

The disease primarily affects the central face but extrafacial areas may also be affected including the chest, neck, ears and scalp. There is often an overlapping of clinical features, but in the majority of patients, a particular manifestation of rosacea dominates the clinical picture. As a useful approach to the guidance of therapy, the disease can thus be classified into four subtypes:

1. Erythematotelangiectatic

2. Papulopustular

3. Phymatous

4. Ocular

In practice, patients often experience a range of symptoms spanning more than one subtype and fluctuating in terms of symptoms present and severity. These consist of face flushing, the appearance of telangiectases and persistent redness of the face, eruption of inflammatory papules and pustules on the central face, and lymphoedema. Hyperplasia of the connective tissue and sebaceous glands commonly affects the nose (rhinophyma) but also presents on the chin, forehead, ears or eyelids. Ocular changes have been diagnosed in about 50% of patients and range from mild dryness and irritation with blepharitis and conjunctivitis (common symptoms) to more severe manifestations leading to vision impairment.14 Patients with rosacea may report increased sensitivity of the facial skin and may have dry, flaking facial dermatitis and facial oedema. The severity of each subtype is graded as 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe). The psychological, social, and occupational effects of the disease on the patient should also be assessed and factored into treatment decisions. Using a dermatology quality of life questionnaire (DLQI) specifically designed to measure the impact of rosacea on the individual, allowing a comprehensive assessment of the psychosocial impact the disease has on the patient.15,16

DIAGNOSING ROSACEA

The most obvious and prominent feature noticed in rosacea is erythema (redness).

Erythema frequently starts as just flushing and blushing that, over time, becomes persistent. Another prominent feature is telangiectasia – dilated and broken blood vessels visible just under the surface of the skin. The patient may also present with inflammatory lesions, presenting as papules and pustules. These are the main three features, but not everybody has all three – they may have more or fewer visible symptoms. Patients may also describe ocular symptoms, oedema (swelling) or tissue changes to their noses, chin and forehead, or tenderness or pain.

Where we see these symptoms is also important for the diagnosis. Symptoms tend to affect the middle of the face, on the facial convexities. There is a wide spectrum of disease with rosacea, which is classified into four subtypes.17

Subtype I – erythematotelangiectatic rosacea

This is a common type, characterised by the typically red face with flushing, and often persistent erythema.17 Patients tend to have extraordinarily sensitive skin, which is one of the most challenging aspects of managerment. Most of the time, these patients do not have inflammatory papules or pustules.

Signs and symptoms

- Flushing and persistent central facial redness (erythema)

- Telangiectasias (small dilated blood vessels) are common but not essential and usually prominent on the cheeks and nose

- Central facial oedema

- Stinging and burning sensations

- Roughness or scaling

Prevalence

Most common form of rosacea, estimated to affect about 75% of patients

Distinguishing features

- Can have sensitive skin that is intolerant to topically applied products

- Often report long history of flushing in response to a variety of stimuli

- Characteristic sparing of the periocular region

Flushing and persistent facial erythema

Flushing, with persistent central facial erythema (erythematotelangiectatic rosacea), is probably the most common presentation of rosacea.18,19 Flushing describes transient episodic attacks of redness of the skin together with a sensation of warmth or burning of the face and neck, caused by increased blood flow through the skin. Repeated flushing over a prolonged period can lead to telangiectasia and persistent erythema as a result of blood vessel engorgement.

Differential diagnosis

Flushing can be caused by different common conditions or triggers, should be explored when a medical history is taken. These include:18

- Menopause

- Climatic conditions

- Excessive heat, cold, or humidity

- Neurological conditions, e.g. Anxiety, migraine, Parkinson’s disease

- Certain foods or drinks

- Hot, spicy foods

- Hot beverages

- Alcohol

- Some dairy, fruit, or fish

- Drugs and interactions with alcohol

Patients who report flushing as their only symptom should not immediately receive a diagnosis of ‘prerosacea’. If episodes of flushing are prolonged and not limited to the face, accompanied by sweating and systemic symptoms such as diarrhoea, wheezing, headache, palpitations, or weakness, certain rare conditions should be considered, including carcinoid syndrome, phaeochromocytoma, or mastocytosis.

Skin biopsies, serologic screening, or other investigations may be necessary to differentiate the flush of rosacea from facial contact dermatitis, lupus erythematosus, or photosensitivity.

Subtype II – Papulopustular rosacea

Signs and symptoms

- Persistent central facial erythema with transient papules, pustules, or both in a central facial distribution (inflammatory papulopustular rosacea)

- Burning and stinging may also occur

- Telangiectasias are often present but may be obscured by the erythematous background

Prevalence

- Accounts for about 25 % of all cases

Differential diagnosis

- Acne vulgaris: less erythema, generally younger patients with oily skin, presenating with blackheads and whiteheads (comedones), larger pustules and nodulocystic lesions, and a tendency to scarring

- Perioral dermatitis presents with micropustules and microvesicles around the mouth or eyes and dry, sensitive skin, often after inappropriate use of topical corticosteroids

- Seborrheic dermatitis presents with yellowish scaling around the eyebrows and alae nasi (wings of the nose), together with troublesome dandruff but may accompany rosacea and contribute to the facial erythema

Subtype III – Phymatous rosacea

Signs and symptoms

- Sebaceous tissue has become bulbous and disfiguring leading to skin thickening, irregular nodular skin

- Phymatous rosacea most often affects the nose (rhinophyma)

- Changes can be observed in other locations, including the chin, forehead, cheeks, ears and eyelids

Prevalence

- Affects less than 5% of male and approximately 1% of female rosacea patients

Distinguishing features

- Men with rosacea are significantly more likely to develop phymatous changes

The diagnosis is usually made on a clinical basis, but a biopsy may be necessary to distinguish atypical, or nodular, rhinophyma from lupus pernio (sarcoidosis of the nose); basal-cell, squamous-cell, and sebaceous carcinomas; angiosarcoma; and even nasal lymphoma

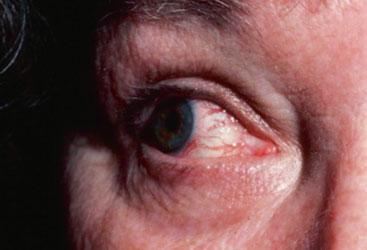

Subtype IV – Ocular rosacea

Signs and symptoms

- Watery or bloodshot eyes, foreign-body sensation, burning or stinging, dryness, itching, light sensitivity, blurred vision and telangiectasia in the conjunctiva and lid margin

- Lid and periocular erythema, blepharitis, conjunctivitis and irregularity of the eyelid may also be present

- The risk of vision loss is relatively rare

Prevalence

- Found in at least 50% of rosacea patients

Distinguishing features

- Ocular rosacea may precede the onset of cutaneous symptoms by many years

Ocular rosacea is common but often not recognised by the clinician.5 It may precede, follow, or occur simultaneously with the skin changes typical of rosacea and in the absence of accompanying skin changes, ocular rosacea can be difficult to diagnose, and there is no test that will confirm the diagnosis. Persistent or potentially serious ocular symptoms should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

Rosacea variant – Granulomatous rosacea

Signs and symptoms

- Hard, yellow, red, or brown nodules or papules

- May be severe and lead to scarring

- Presence of other rosacea signs is not guaranteed

Prevalence

- Very rare

Distinguishing features

- Inflammation is rare

- Absence of sensitivity to topical agents

TREATMENT

Currently the goal of treating rosacea is to manage the condition, as there is currently no cure. All treatments are aimed at controlling the disease, preventing complications and improving quality of life.13 Management strategies for patients should be tailored to the specific subtype(s) and require the patient’s understanding of their diagnosis and management options.

Regardless of subtype, all rosacea patients should:

- Regularly apply a combined UVA- and UVB-protective sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or greater

- Use soap-free cleansers, and products for sensitive skin

- When possible, avoid trigger factors

- Be reassured that the condition can be successfully managed, and that rhinophyma is very rare (particularly in women)

- Be directed to websites such as the National Rosacea Society (www.rosacea.org)

- Be advised to keep a daily diary to identify trigger factors

Management strategies should be tailored to alleviate the individual’s presenting symptoms. It is an important role of the health care professional to educate the patient about lifestyle changes (trigger factor avoidance) and the treatments available. It is essential that the individual with rosacea understands what the treatment(s) aim(s) to achieve. To effectively support the patient with rosacea the following should be considered:

- What is the psychological impact of disease on the patient?

- Will the patient be able to comply with the treatment?

- Does the patient understand the suggested therapy?

- Does the patient understand possible side effects and how to manage them?

- Is the patient motivated and do realistic expectations exist?

Recommended topical and oral preparations for rosacea, together with adjunct measures are summarised in Table 1.

Topical treatments

Topical Metronidazole

Metronidazole is an antibacterial and antiprotozoal agent therapeutic benefits in rosacea are mostly derived through its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.22 Topical metronidazole decreases the number of inflammatory lesions and reduces erythema and is generally well tolerated, has a low incidence of adverse effects, and is effective in maintaining remission, and once-daily dosing has been shown to be as effective as twice-daily application.23 Patients can chose between cream and gel formulation.

Topical Azelaic Acid

Azelaic acid is a naturally occurring dicarboxylic acid approved for the treatment of mild to moderate rosacea and is licensed for the treatment of rosacea applied as a 15% gel and can attribute its efficacy to anti-inflammatory, anti-keratinizing, and antibacterial effects. Azelaic acid also has a relatively low incidence of adverse effects, with burning, stinging, and irritation being the most commonly reported. The incidence of side effects is greater with azelaic acid compared with metronidazole, but these effects are generally mild and transient. Although the conventional regimen is twice-daily application of azelaic acid, once-daily dosing has been found to be equally effective.23

Brimonidine tartrate 0.33% gel

Brimonidine tartrate 0.33% gel, approved in the UK since 2014, is the first topical agent approved for the treatment of facial erythema of rosacea. Brimonidine (initially available in prescription eye drops for the treatment of glaucoma) is a highly selective α-2 adrenergic receptor agonist with potent vasoconstrictive activity. (Beta-blockers in low doses, as well as clonidine and spironolactone have been used to treat flushing in patients with rosacea, but evidence for their effectiveness is limited).17

Oral therapies

Tetracyclines, doxycycline and erythromycin

The therapeutic benefits of tetracyclines in rosacea are their anti-inflammatory rather than antibacterial properties. Tetracycline-family antibiotics should particularly be considered in the presence of ocular rosacea.

Tetracyclines are contraindicated in pregnancy and erythromycin is a suitable alternative.

A sub-antimicrobial dose of 40 mg doxycycline administered daily to patients with moderate to severe rosacea significantly reduces total inflammatory papule and pustule counts and because of the low dose, prevalence of adverse effects is low and only marginally higher than placebo, with no cases of photosensitivity or vaginal candidiasis.24

Oral isotretinoin

Oral isotretinoin is used off-label for the treatment of more severe or persistent cases of papulopustular rosacea. In low doses it has been reported to be effective in the control of rosacea that was otherwise resistant to treatment and may help slow or halt the progression of rhinophyma. The ocular and cutaneous drying effects of this agent are poorly tolerated, and its potential for serious adverse effects (including teratogenic effects) contradicts its use in routine care.

Other and emerging therapies

Topical Ivermectin

Several topical acaricidal agents (permethrin 5%, crotamiton 10%, and ivermectin 1%) have been studied for the treatment of rosacea, all of which primarily target Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis mites. The potential aetiological role of these mites in rosacea has been debated for many years,25 but there is renewed interest in Demodex mites as a result of recent studies that demonstrated antigenic proteins produced by a Demodex-isolated bacterium (Bacillus oleronius) may aggravate the inflammatory responses in papulopustular, ocular and erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. This pathogenic scenario implicating the bacterium rather than the Demodex mites themselves may explain the efficacy of antibacterial therapies in rosacea.9

Laser and light therapies have been used successfully. Pulsed dye laser and intense pulse light modalities were found to be effective in reducing erythema and telangiectasia in patients with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea.26

CONCLUSION

Rosacea is a diagnostic term applied to a spectrum of changes in the skin and eyes. It is a chronic disease, with remissions and relapses. Prompt and appropriate treatment is crucial to avoid psychological and social suffering, and referral to a dermatologist should take place if the psychological impact becomes a concern or if the patient does not respond to treatment.

The condition may improve with management and avoidance of trigger factors. Inflammatory changes in the skin are usually responsive to medical therapies and heal without scarring, whereas telangiectasias and phymatous changes often require laser or surgical intervention. Ocular rosacea is usually mild and responsive to lid hygiene, tear replacement, and systemic antibiotics, but patients with persistent or severe ocular disease should be referred to an ophthalmologist. All patients should be advised about protection from climatic influences (both heat and cold), avoidance of factors that trigger or exacerbate flushing or that irritate the often-sensitive skin, and appropriate care of the facial skin.

There are numerous treatment options available for rosacea and therapeutic decision-making should be guided by high-level evidence and patient-specific factors, such as rosacea subtype, severity, treatment expectations, tolerance, cost, and previous response to therapy. Topical azelaic acid and metronidazole are considered safe and efficacious first-line therapies. Oral antibiotic therapy plays a crucial role in the management of moderate to severe and ocular rosacea. A sub-antimicrobial dose of doxycycline is the best research-supported oral therapeutic option and can be used to treat moderate to severe forms of papulopustular or ocular rosacea, or in patients who may be more adherent to a systemic regimen. Low-dose isotretinoin or surgical interventions may be indicated for the phymatous type. Light and laser-based therapies can play a major clinical role in the treatment of the telangiectatic component. Brimonidine gel is the first of its kind for the treatment of persistent facial erythema.

A comprehensive treatment plan must also incorporate non-drug strategies aimed at quality of life improvements should include trigger avoidance, proper daily skin care, camouflaging and photo-protection.

Timely intervention, correct treatment and compliance are key to successful rosacea management.

REFERENCES

1. British Association of Dermatologist (2014). Rosacea patient information leaflet http://www.bad.org.uk/for-the-public/patient-information-leaflets/rosacea#.VJggzF4gKAA

2. Spoendlin J, Voegel JJ, Jick SS, et al. A study on the epidemiology of rosacea in the UK. Br J Dermatol 2012;167: 598–605.

3. Powell, F. C. 2014. Rosacea: One disease or many? Primary Care Dermatology Society. PCDS Bulletin Autumn 2014. http://www.pcds.org.uk/ee/images/uploads/bulletins/Aut_Bull-14-web.pdf

4. Gieler U, Kupfer J, Niemeier V, et al, Psyche and skin: what’s new? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2003;17:128–30.

5. Powell FC. Rosacea: Diagnosis and Management. New York: Informa Healthcare USA; 2009

6. Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Chen SJ, et al. Comorbidity of rosacea and depression: an analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey. Br J Dermatol 2005; 153(6):1176-81

7. Reinholz M, Tietze JK, Kilian K, et al. Rosacea – S1 Guideline. JDDG: Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 2013;11:768–780. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12101 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ddg.12101/full

8. Jarmuda S, O’Reilly N, Åaba R, et al. Potential role of Demodex mites and bacteria in the induction of rosacea. J Med Microbiol November 2012; 61(11): 1504-1510.

9. Stein Gold L, Kircik L, Fowler J, et al. Efficacy and safety of ivermectin 1% cream in treatment of papulopustular rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014 March; 13(3): 316–323

10. Forton FM. Papulopustular rosacea, skin immunity and Demodex: pityriasis folliculorum as a missing link. JEADV 2012; 26:19–28

11. National Rosacea Society Rosacea review. Rosacea Patients Feel Effects of Their Condition in Social Setting, 2012. http://www.rosacea.org/rr/2012/fall/article_3.php

12. National Rosacea Society. Rosacea Triggers Survey, 2014. http://www.rosacea.org/patients/materials/triggersgraph.php

13. Oliver P, Courtney M. The Red Face: Recognising and managing Rosacea. Primary Health Care 2010;20(3)

14. Mauri-Sole J. (2006) Management options in rosacea. MIMS Dermatology 2006;2(2):36-37

15. Finley A. The Dermatology Life Quality Index. MIMS Dermatology 2006;2(2):12

16. Cardiff University. Dermatology Life Quality Index or DLQI, 2014. Department of Dermatology Cardiff University School of Medicine http://www.dermatology.org.uk/quality/dlqi/quality-dlqi.html

17. Del Rosso JQ. Advances in understanding and managing rosacea: part 2: the central role, evaluation, and medical management of diffuse and persistent facial erythema of rosacea. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2012;5(3):26–36.

18. Greaves MW. Flushing and flushing syndromes, rosacea and perioral dermatitis. In Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns T, Breathnach S (eds): Rook/Wilkinson/Ebling Textbook of Dermatology, 6th ed, vol 3. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific, pp 2099-2104; 1998

19. Greaves MW, Burova EP. Flushing: causes, investigation and clinical consequences. JEADV 1997;8:91–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.1997.tb00196.x

20. British National Formulary (BNF) 2015 online - 13.6 Acne and rosacea https://www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/bnf/current/PHP7791-acne-and-rosacea.htm

21. NICE. Clinical Knowledge Summaries, 2015. Rosacea http://cks.nice.org.uk/rosacea#!scenario

22. Narayanan S, Hunerbein A, Getie M, et al. Scavenging properties of metronidazole on free oxygen radicals in a skin lipid model system. J Pharm Pharmacol 2007;59(8):1125–30

23. Po-Yen Chang B, Kurian A, Benjamin Barankin B. Rosacea: An Update on Medical Therapies. Skin Therapy Letter. 2014;19(3) http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/826560_2

24. Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, Jackson M, et al. Two randomized phase III clinical trials evaluating anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline (40-mg doxycycline, USP capsules) administered once daily for treatment of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 May;56(5):791–802.

25. Layton A, Thiboutot D. Emerging therapies in rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 69(6) Suppl 1:S57–65

26. Neuhaus IM, Zane LT, Tope WD. Comparative efficacy of nonpurpuragenic pulsed dye laser and intense pulsed light for erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Dermatol Surg 2009;35(6):920–8

Related articles

View all Articles