Safeguarding children: how primary care audit can help us do it better

Leah Hughes

Leah Hughes

Advanced Nurse Practitioner

Sherborne, Dorset

Practice Nurse 2020;50(8):26-29

Failures in child safeguarding hit the news headlines too often. A particularly poignant case was the subject of a serious case review, and prompted us to audit our own practice

CASE STUDY

Serious case review S25 Child M1

Child M was murdered age two-and-a-half in 2016, by her mother’s new partner. The review found that multiple agencies were involved in the four months before the child’s death, including a social care review, which was signed off as ‘no safeguarding concerns’ just two weeks before her death.

The child had been admitted to an Emergency Department with a serious facial cut, and health visitors had trouble contacting the mother, which was unusual. The mother had increased contact with her GP, attending five times in one month. The family had moved, and their address was not accurate, meaning that there was both a delay in social care home assessment, and a home visit from the health visitor teams.

THE PRACTICE

The Grove Medical Centre is situated in the market town of Sherborne, Dorset. There are currently just over 12,500 patients registered, of whom about 2,400 are children under 18 years old. The patient list contains a diverse socio-economic group, including pockets of deprivation and a rural population with poor local transport.

We are large team, with nine GP partners, one nurse practitioner, three practice nurses, four healthcare assistants (HCAs), and one community HCA. All clinicians take responsibility for safeguarding and are required to complete level 3 safeguarding training through e-Learning for Healthcare and a face to face teaching session. Two GPs have completed level 4 and take the lead on safeguarding children within the practice.

After being involved in a safeguarding case within the practice I have recently become part of the in-house safeguarding team.

Clinicians can create a ‘waiting list’ of any patients of concern on the practice computer system. The list allows them to monitor patients and is useful for multidisciplinary team discussion as the list is not separate to the patient’s notes, and no further pieces of paper with confidential information are required. The health visitor, however, does not have access to this list and is provided with a different list. The disadvantage of this was that safeguarding meetings were lengthy, with no clear structure. It also meant that documentation after the meeting was time consuming.

THE SAFEGUARDING TEAM AND MEETINGS

The safeguarding team is made up of two GPs, the nurse practitioner, one practice nurse and a health visitor, who is employed by another organisation. The health visitor covers a large area and is not exclusively linked to the GP surgery.

Clinicians add any patient of concern to a ‘waiting list’ on the computer system, for multi-disciplinary team discussion.

We meet once a month to discuss patients of concern. This discussion is documented in the patient’s electronic journal and may result in the patient’s usual GP actioning a task, or a member of the team obtaining further information.

Meetings always had good discussion, but documenting the discussion, in some cases on several children’s notes, was an onerous task for one person after the meeting. In addition we had no real list of whom we had discussed from meeting to meeting. This sometimes results in the same families being discussed repeatedly, with no real change in outcome for the patients and their families.

WAYS TO IMPROVE?

Chapter 4 of ‘Working together to Safeguard Children’2 outlines ways professionals and organisations can reflect of the quality of their own service and learn from their own practice.

Audit is a recognised management technique demonstrating an overview of the present situation regarding specific resource(s) and services within an organisation.3 It can help reflect on current practice, enabling practitioners to identify and analyse problems and problem solve.4 Auditing adheres to the NMC code of conduct – prioritising patients and preserving safety.5

In essence, audit is essential for

- Analysing current care

- Evaluating practice, and

- Introducing change.

THE AUDIT

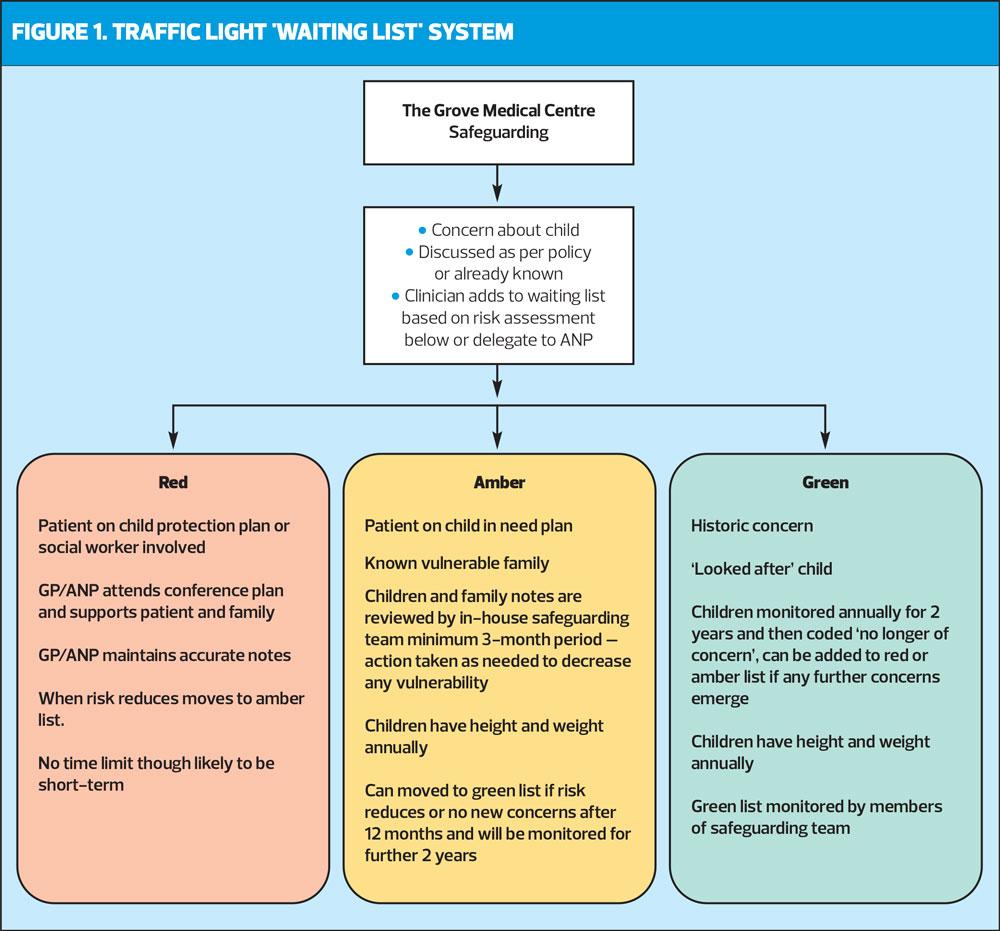

I decided to audit the notes of children who had a safeguarding code documented in their records in order to become more familiar with the families on our caseload, and to see whether any improvements could be made in the way we currently manage our in-house safeguarding meetings. Themes were identified and a traffic light system of risk was introduced to identify risk and ultimately to reduce vulnerabilities. This traffic light system will be discussed in more detail later in this article.

Method

A search of the practice computer system was undertaken. The codes used included:

- Child on protection register

- Child protection plan

- Subject to child protection plan

- Unborn child subject to child protection plan

- Child on child protection plan

- Child protection category

- Child protection administration

- Child at risk

- Child on risk register

- Child is cause for safeguarding concern

- Safeguarding child concern.

Any duplicate patients were removed and the patients' notes reviewed.

Codes were corrected as notes were examined. This was accomplished with the help of a medical secretary as the task would have been too time consuming to do alone.

Where necessary, the GPs of ‘Safeguarding/vulnerable families’ were changed to ensure that all members of the family were registered with one GP. This was vital for consistency of care and allows a holistic approach.

Results

I reviewed 192 patients’ notes over a period of 5 months from February 2020 to June 2020. This allowed consistency in the review. During this time the UK went into lockdown due to COVID-19. Patient attendance and contact decreased at the surgery during this time, and I was able to use this time to complete the audit. Several emerging themes were identified:

- Incorrect coding was a problem. For example, attendance at a minor injuries unit (MIU) was coded as a safeguarding concern, and then ‘No’ was added as a free text. Historic coding needed to be updated and there was a lack of information when a case was closed in order to complete the code accurately. Inaccurate or historic coding triggered an alert, though the reason was hard to find in some cases and whole reports needed to be reviewed.

- Siblings and parents were registered with different GPs.

- Some patients had not been flagged up to the GP and therefore there was no GP involvement in safeguarding cases at conference level.

- Some patients who had an alert had not been seen in the surgery for some time.

ACTIONS AS A RESULT OF THE AUDIT

As the notes were reviewed, a traffic light colour coding system was put in place (Figure 1).

Red

Red indicates that the patient is deemed to be at high risk of potential serious harm. The lead on care is likely to be a social worker, and the GP/ANP has regular contact.

A child protection plan may already be in place. Alternatively the clinician may be aware of a parent’s acute deteriorating mental health/substance misuse or domestic violence that may pose a risk to the child or family, and a child protection plan may be imminent.

Patients on the red list will be managed by their registered GP or ANP, who will attend case conferences as time allows. Clinicians are likely to already be involved in care, therefore they need less discussion at the safeguarding meetings. However, the safeguarding team and wider clinical team will be aware of all patients on the ‘red list’ so that prompt action is taken if concern is escalated.

Concern will be escalated according to the practice’s safeguarding policy. Patients on the red waiting list will have a patient plan in the notes giving details of their social worker. This will automatically draw the clinician’s attention and they will be alerted to follow up any A&E attendances and missed appointments.

Amber

Amber is used to represent vulnerable patients/families: those that need extra support, but do not have a current child protection plan. They may be on a ‘child in need’ plan, or have longer term parental concerns, though they may not necessary be a concern at present.

Patients on the amber list will be reviewed on a three-to-four-month basis and discussed at the team safeguarding meeting. This group is about ‘identification of risk and reducing vulnerability.’ Ensuring that all individuals in this group have a regular review means support can be offered proactively. A list of their vulnerabilities means meetings are more structured, ideally preventing a crisis and minimising any potential harm. If there are no new concerns or risk reduces after 12 months, they will be moved to the green waiting list.

Green

Green is used to represent historic coding/incorrect coding and when there is no longer any acute concern.

Patients on the green waiting list will be reviewed annually. This will include a height and weight check, which gives the opportunity for a face-to face consultation. A trend in height and weight will highlight concerns of physical neglect, or emotional concerns in the case of eating disorders. It allows the patient or parent a chance to voice concerns. This review will also provide an opportunity for the clinician to ask the parent/guardian about optician and dentist appointments, and to ask the child about accidents, and what it is like to live in their household. Talking to the child is essential to ensure a child-centred approach.6

If there are no new concerns after 2 years, patients will be removed and coded as ‘child no longer a safeguarding concern’, meaning codes remain current, as much as possible.

An action point is to include an explanation note when patients are transferred under the colour coded traffic light system onto waiting lists. This means that on opening the notes an alert is displayed, so the clinician can easily identify the risk level and any prevention work completed.

DISCUSSION

This audit examined our current practice. It took a qualitative, thematic approach in order to highlight discrepancies and suggest any changes required to the practice’s safeguarding policy.

It is accepted that GPs are in a unique position in regard to child safeguarding as they often have a duty of care for both the adult who poses a risk to a child and for the child who is at risk,8 but their role is broader than simply recognising potential harm and making referrals. It includes lesser grades of action throughout the continuity of their relationships with children and their families, and acting as an advocate.9

One of the observations was that some children had been allocated safeguarding codes because they had special educational needs or a learning disability and not necessarily because of a safeguarding issue. There is a fine line between children that present with learning disability and safeguarding issues. For me, ‘a safeguarding issue’ is when there is a perceived or actual risk of harm to the child, through neglect: neglect of emotional needs, sexual or physical health, or fabricated illness, because the parents or guardians are not protecting the child from harm.7 However, safeguarding and child protection plans carry a lot of stigma, and not all children with special needs or a learning disability are at risk. As clinicians we need to ensure that we act as an advocate for those parents that DO protect and nurture their children, even though these children have more complex needs.

Communication remains key and the audit demonstrated the lack of communication we have with the local authority secondary school. An example of this was a 3-week wait in obtaining attendance figures to highlight whether there was a concern. In contrast there were solid links and clear communication lines between the practice and the local primary schools. Partnership working with children, young people and families should remain central to all care.10 Nearly all failures of child safeguarding involve failures of communication between partners or agencies.5 A direct action as a result of the audit was to attend the secondary schools multi-disciplinary team safeguarding meetings.

Discussion has also taken place around the possibility of there being a ‘practice link nurse’ to enable direct email or telephone contact with social workers. This would enable easy communication to take place and we developed a job description for this role, encompassing communication, training, auditing and leadership within the practice.

We have been informed that social care services are changing the way they work, and the surgery will be allocated one social worker for the practice. This will enable the relationship between the practice and social care services to develop and further improve the outcomes for this vulnerable group of patients. It would also be beneficial for the school nurse to attend the safeguarding meetings but, after discussing this with them, they have confirmed that this is not possible due to the large area and number of practices they cover. This would appear to make the role of link nurse more critical.

During the COVID-19 lockdown period (23 March – 23 June 2020) the case conferences and reviews have been easier to attend as telephoning patients rather than carrying out face-to-face consultations has meant GPs’ work patterns have been more flexible. This has allowed them to have a greater input into care and to obtain information at first-hand. It would be beneficial for video conferencing to be retained. By eliminating travel time, it makes attendance easier for the key professionals who have direct knowledge of their patients.

CONCLUSION

This audit allowed us to review the notes of individuals where there is, or has been, child safeguarding concerns. The audit has attempted to correct codes where possible. However, the audit also identified that some of these codes are beyond our control, resulting in an incorrect safeguarding triangle being displayed.

In order to manage the level of risk a traffic light colour coded waiting list has been implemented. This allows easier identification of the level of risk. The colour coded list facilitates regular review and discussion within the safeguarding team and can help prevent deterioration by highlighting concerns earlier so that patients can be proactively contacted by a professional they know. The benefit of this is currently untested, but has huge potential for success.

The audit has allowed relationships with the local secondary school to be formed. A clinician from the surgery can attend their safeguarding meetings (once COVID restrictions are lifted) and it is hoped that this will also provide a platform for concerns to be highlighted earlier, risks identified, vulnerability reduced and will lead to a more joined up approach in working.

This joined-up approach to working will hopefully be strengthened with the allocation of a named social worker to the surgery, and the appointment of a link nurse. Ideally there would be CCG funding for the link nurse role so that this could be implemented in all GP surgeries.

By creating a waiting list an annual re-audit will be manageable and may result in further themes being identified and further changes and improvement to the safeguarding policy and, to better patient outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. Dorset safeguarding children’s board, 2016 https://pdscp.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/SCR-Overview-Report-Family-S.25-2017.pdf

2. HM Government. Working Together to Safeguard Children.

A guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children: 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/working-together-to-safeguard-children--2

3. Relji N, Majda Pajnkihar, M, Fekonja Z. Self-reflection during first clinical practice: The experiences of nursing students. Nurse Education Today 2019;72: 61-66.

4. Botha H, Boon JA. The information audit: principles and guidelines. Libri 2003;53(1):23-38.

5. Nursing & Midwifery Council. The code: Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates; 2018. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/

6. Peckover S, Trotter F. Keeping the focus on children: the challenges of safeguarding children affected by domestic abuse. Health & Social Care in the Community 2015;23(4):399–407.

7. Green P. The role of designated and named professionals in child safeguarding, Pediatrics and Child Health 2019;29;(1):1-5

8. Jackson B, Tomson M. Embedding a sustainable skills-based safeguarding children course across multiple postgraduate general practice training programmes. Education for primary care 2017; 28(1), 59–62

9. Woodman J, Rafi I, de Lusignan S. Child maltreatment: time to rethink the role of general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2014; 64(626):444–445.

10. Royal College Nursing. Getting it Right for Children and Young People: Self-assessment tool for general practice nurses and other first contact settings providing care for children and young people; 2017. https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-006507

Related articles

View all Articles