Optimising self-management for people living with heart failure

Beverley Bostock-Cox

Beverley Bostock-Cox

RGN MSc MA QN

Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery

PCN CVD Lead Hereford

Primary Care Cardiovascular Society Council member

Practice Nurse 2022;52(8):11-15

General practice nurses are well placed to recognise the symptoms of heart failure both when they first develop and if they deteriorate and can provide valuable support for patients, facilitating self-management

Heart failure is a syndrome made up of a range of symptoms and underlying pathologies. In the past few years, as the result of new research and changes to medication licences, there has been a renewed focus on optimising the management of heart failure in order to improve quality of life and outcomes. Undiagnosed and decompensated heart failure is the cause of a significant number of hospital admissions and people living with heart failure have a prognosis which can be as poor as, or even worse than some cancers.1,2 Primary care clinicians, including general practice nurses (GPNs) are well placed to recognise the symptoms of heart failure de novo and in decompensation. GPNs can also support people with heart failure through appropriate pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, facilitating self-management where appropriate.

By the end of this article, you should have a better understanding of:

- What heart failure is

- How it is managed

- How to improve patient engagement with self-management

- How the Heart Function Diary can support you and people living with heart failure to achieve better outcomes

The NHS Long Term Plan highlights heart failure as a priority, not least because 80% of heart failure is currently diagnosed in hospital, despite 40% of patients having symptoms that should have triggered an earlier assessment in primary care.3 NHS England’s new project ‘Managing Heart Failure @home’ encourages a personalised care approach to remote support and monitoring using an integrated care approach which improves self-efficacy and enables timely interventions. The aim is to reduce avoidable hospital admissions.4 GPNs need to be aware of how to enable those living with heart failure to self-manage and to be confident about knowing when to seek further input.

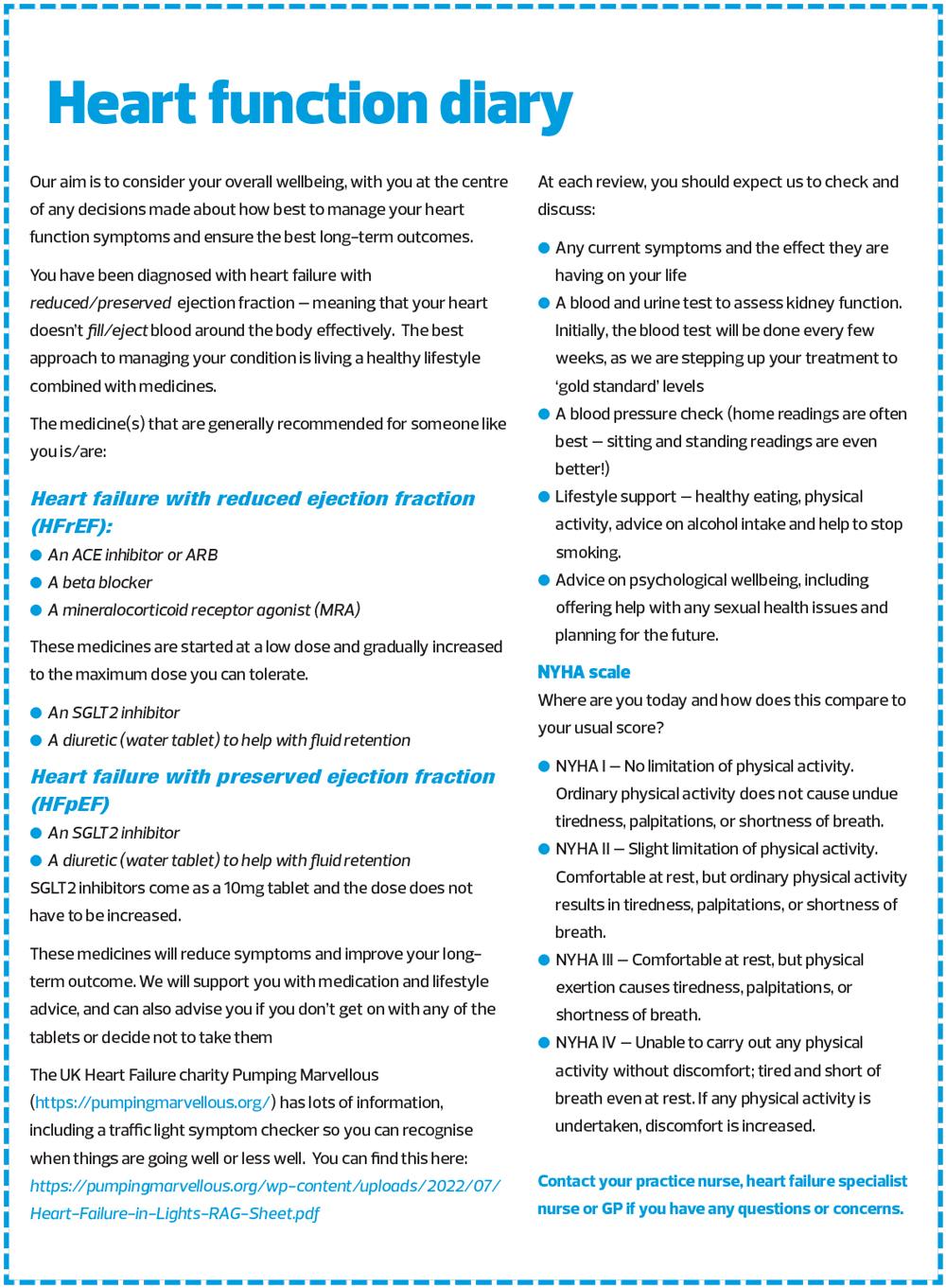

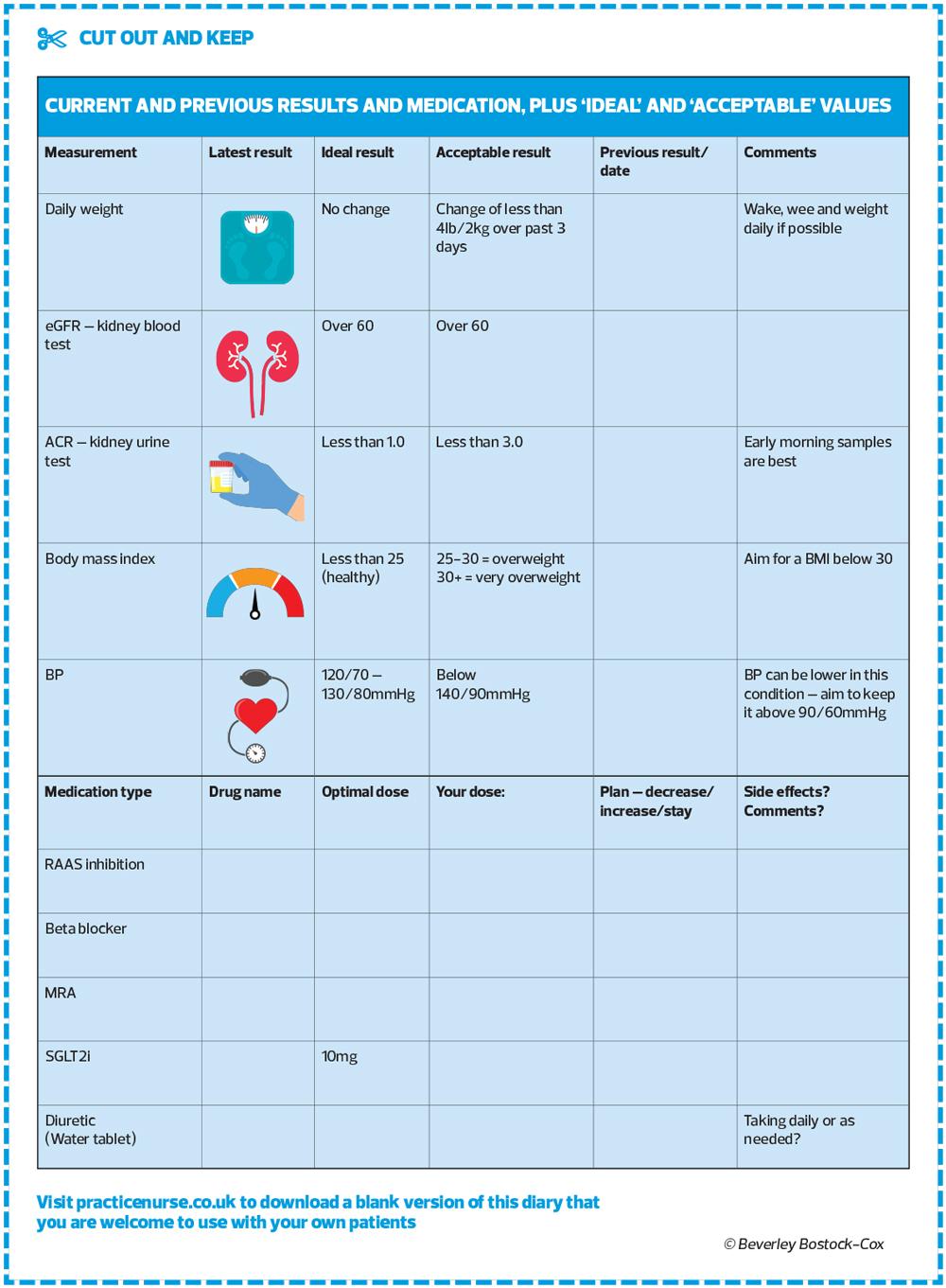

In a previous article, I shared my ‘Diabetes Diary’ which I developed to show people with diabetes what their values were, how they compared with their previous readings and with acceptable or ideal values.5 This article describes a new concept – that of the heart failure (or heart function) diary, which crystallises the areas that should be covered for a holistic, person-focused heart failure review, which incorporates shared decision making based on a mutual understanding of evidence-based practice and the experience and preferences of the person living with heart failure.6 Practice Nurse readers may like to use this as it stands or base their own design around this example.

WHAT IS HEART FAILURE?

Heart failure is a clinical syndrome characterised by symptoms such as breathlessness, ankle swelling and fatigue along with signs which may include a raised jugular venous pressure, pulmonary crackles or peripheral oedema resulting in an inability to meet the circulatory demands of the body.7 Risk factors for heart failure include increasing age, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and other conditions.8

In the presence of risk factors and symptoms, assessment should include measurement of NT-proBNP with any reading over 400 ng/L being suggestive of a diagnosis of heart failure and a reading of 2000 ng/L or more requiring urgent assessment. The NT-proBNP blood test is an important predictor of heart failure so should be carried out in anyone where heart failure is suspected. Referral for echocardiography can then be made in an appropriate and timely fashion. At this time, NT-proBNP testing continues to be underused in primary care so GPNs may like to consider adding this to blood forms when investigating people for breathlessness.

An echocardiogram will confirm the ejection fraction, diastolic filling capacity and any structural abnormalities, and the diagnosis can then be confirmed.

There are three main sub-categories of heart failure – heart failure with reduced ejection fraction of 40% or less on echocardiogram (HFrEF), heart failure with preserved ejection fraction of 50% or more (HFpEF) and heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) – between 41-49%.7 To read more about the diagnosis of heart failure, see our previous article on this topic.9

RECOGNISING THE LINK BETWEEN SIGNS, SYMPTOMS AND DECOMPENSATION

The focus of heart failure management should be to optimise quality of life and reduce the risk of decompensation (acute exacerbations) through appropriate lifestyle and pharmacological interventions.

Common causes of decompensation include anaemia, atrial fibrillation, non-adherence to medication or lifestyle advice (e.g., low salt diet or alcohol restriction), infections and, as noted above, acute decompensated heart failure is one of the most common reasons for hospital admissions.10 Education is therefore essential to ensure that people understand why recommendations are made regarding medication and lifestyle changes, and also to increase awareness of possible triggers for decompensation which might need to be reported, such as infections. This information might also support informed decision making on infection avoidance through vaccinations and hygiene measures.

Using the Pumping Marvellous symptom checker may also remind people about the symptoms that might indicate a possible acute decompensation risk. You can find this here. Signs that heart failure control may be deteriorating include an increase in breathlessness and/or peripheral oedema, fatigue, an increase in weight, all of which might indicate increasing fluid retention. On this basis, many people with heart failure will be advised to practice a daily ‘Wake, wee, weigh’ approach to self-assessment.

PHARMACOLOGICAL AND LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS TO IMPROVE THE WELLBEING OF PEOPLE WITH HF

In HFrEF, the recommended approach to pharmacological interventions is to use the ‘Four Pillars’ approach – renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibition, beta blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) and a sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i).11 Some SGLT2i therapies have now also been shown to reduce mortality and hospitalisations for heart failure and improve functional status in HFpEF.12

People should be aware of the type of heart failure they have (in the same way we would expect people with diabetes to know which type they have) and understand which drug treatments are advised for their heart failure type (including information about target doses) and also be aware of why they are recommended (for their morbidity and mortality benefits). See also the Heart Failure Alliance article on pharmacological management in this issue.

An important element of risk reduction strategies is to ensure that the person living with heart failure understands what we (the person with heart failure and the clinicians involved in their care) are trying to achieve. The Heart Function Diary aims to provide a basis for the opportunity to explain this while at the same time illustrating each individual’s current status, compared with ideal and acceptable values, and drug treatment targets. If a particular treatment is unsuitable for that individual or has been declined by them, a note can be made in the diary.

General advice can be added as to the benefits of cardiac rehabilitation and physical activity in general. A brief reminder about tips for reducing breathlessness (pacing activities, using a hand-held fan) can be useful along with information about why activity-induced breathlessness might not be pleasant but is rarely dangerous. Healthy eating is important, along with advice on alcohol consumption and smoking cessation.

CONCLUSION

People living with heart failure are at risk of episodes of decompensation, not unlike the acute exacerbations experienced by some people with asthma or COPD. It is therefore essential that these individuals can recognise risk factors for, and early signs of, decompensation and can act in a way that reduces the risk of an unplanned admission to hospital. The Heart Function Diary supports shared decision making though the communication of information about heart failure that has been tailored to the individual. The diary provides a starting point for conversations about the condition, and the interventions that might help maintain optimal wellbeing. The diary can be used to inform the heart failure review, and to facilitate open discussions about the way forward. It can be adapted to each individual in order to reflect key areas of importance for the patient and the clinician to discuss. Highlight or delete the italicised options as appropriate to reflect the individual's situation.

The diary can be a useful tool for the person living with heart failure but can also be a helpful aide memoire for the clinician.

REFERENCES

1. The Heart Failure Policy Network. Preventing hospital admissions in heart failure; 2021 https://www.healthpolicypartnership.com/app/uploads/Preventing-hospital-admissions-in-heart-failure.pdf

2. Abdin A, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. 'Time is prognosis' in heart failure: time-to-treatment initiation as a modifiable risk factor. ESC heart failure 2021;8(6):4444–4453. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.13646

3. NHS Long Term Plan. Cardiovascular Disease https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/online-version/chapter-3-further-progress-on-care-quality-and-outcomes/better-care-for-major-health-conditions/cardiovascular-disease/

4. Linker N. Managing Heart Failure @home: An opportunity for excellence; 2022 https://www.england.nhs.uk/blog/managing-heart-failure-home-an-opportunity-for-excellence/

5. Bostock B. Diabetes – putting the patient in control. Practice Nurse 2021;51(4):18-22

6. NICE. Shared decision making; 2021 https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-guidelines/shared-decision-making

7. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;42(36):3599–3726. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368

8. NICE NG106. Chronic heart failure in adults; 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106

9. Clayton L. Diagnosing heart failure using the correct pathway. Practice Nurse 2022;52(7):22-23

10. Platz E, Jhund PS, Claggett BL, et al. Prevalence and prognostic importance of precipitating factors leading to heart failure hospitalization: recurrent hospitalizations and mortality. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20(2):295–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.901

11. Straw S, McGinlay M, Witte KK. Four pillars of heart failure: contemporary pharmacological therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Open Heart 2021;8(1):e001585. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2021-001585

12. Deschaine B, Verma S, Rayatzadeh H. Clinical Evidence and Proposed Mechanisms of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Class Effect? Card Fail Rev 2022;8:e23. https://doi.org/10.15420/cfr.2022.11

Related articles

View all Articles