Lipid management — what's new?

Beverley Bostock-Cox

Beverley Bostock-Cox

RGN, MSc, QN

Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery Moreton in Marsh

Education Lead Education for Health Warwick

In the past the management of dyslipidaemia focused on achieving specific targets for total and LDL cholesterol but the definition of an ‘abnormal’ lipid profile has changed and so have the recommendations for the aims of treatment

Dyslipidaemia is recognised as one of the key risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD),1 so identifying people at risk and acting to reduce that risk should be a priority for general practice nurses. Over the past few years, the definition of what constitutes an abnormal lipid profile has altered and our understanding of who needs treatment and what that treatment should be has followed suit.

In this article, the latest guidelines on lipid management will be evaluated along with the evidence for established and newer lipid lowering therapies.

THE LIPID PROFILE

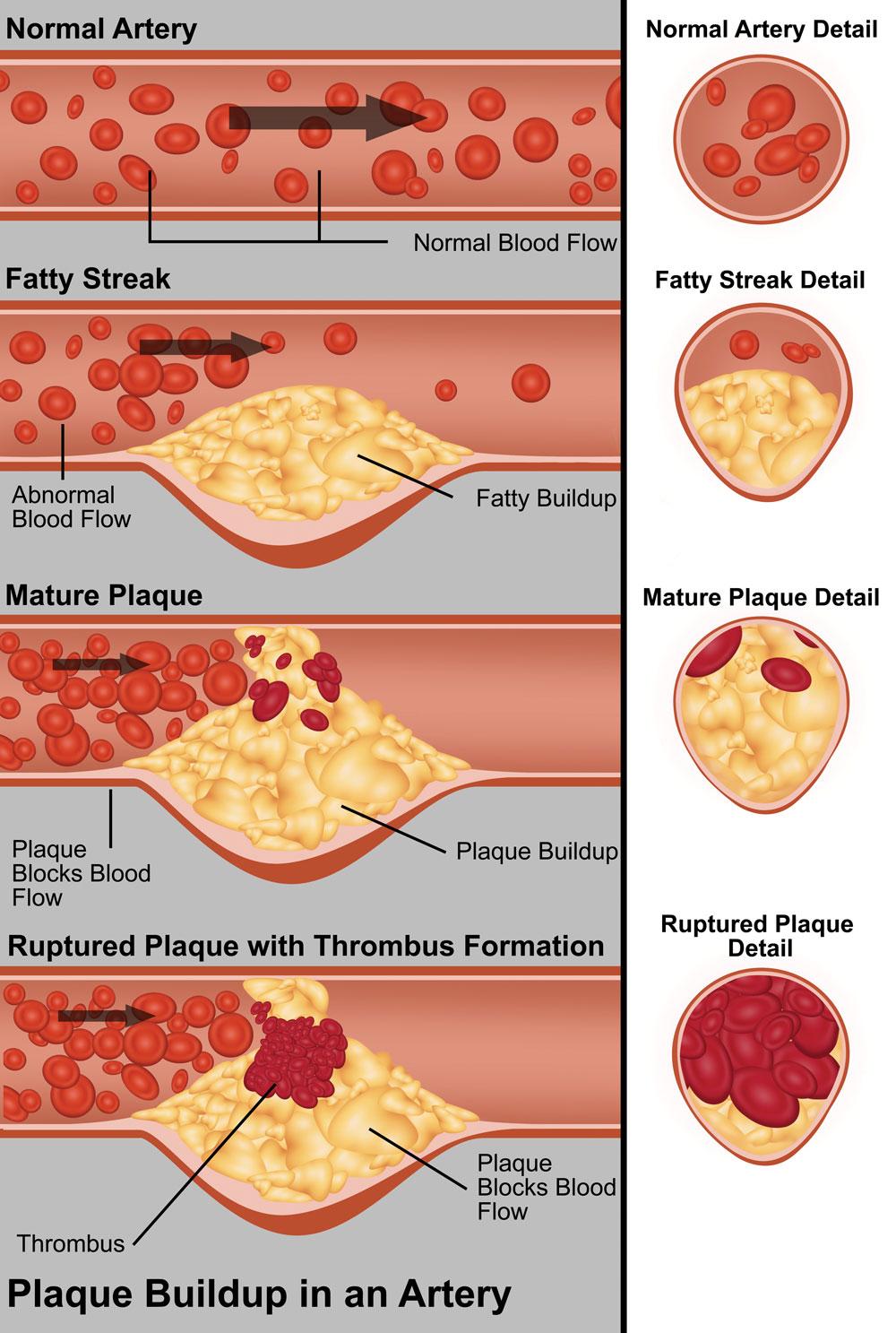

Cholesterol is a naturally occurring substance in the body which is needed for various physiological processes in health; however, its main uses are for making cell walls and in the synthesis of vitamin D.2 However, raised lipid levels are known to be linked to cardiovascular disease and cholesterol laid down in the arteries causes atheroma, which leads to vascular diseases including coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke and peripheral artery disease (PAD).3

In general practice, lipid profiles may be measured as part of a cardiovascular risk assessment (NHS Health Check) or as part of a review of existing cardiovascular disease or diabetes. A full lipid profile, measured after 12 hours of fasting, consists of total cholesterol (TC), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and triglycerides (Tg).4 From these values the laboratory may calculate and report the value of the low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). All of these measurements can provide useful information. HDL-C is known to be protective and higher levels are beneficial to cardiovascular health. Conversely, LDL-C is highly atherogenic and increased levels are linked to higher risk of cardiovascular events.5

INITIAL ASSESSMENT OF RISK

The decision to treat lipid levels will be made on the basis of the QRisk2 score (http://www.qrisk.org). A score of 10% or more suggests that the benefits of treatment are likely to outweigh the risks. However, individual cases will need to be considered based on that person’s views, lifestyle, preferences, life expectancy and co-morbidities. High risk groups should not be risk assessed as they are already known to be at high risk. High risk groups include people with type 1 diabetes who are over 40 or have had diabetes for more than 10 years or who have nephropathy or other cardiovascular risk factors. Other people at high risk include those with familial hypercholesterolaemia, people who have already had a cardiac event and those with chronic kidney disease. People over 85 are also considered to be automatically at high risk but consideration should be given to each case before starting statin therapy. All CVD risk engines require information about the patient’s lipid profile to be entered in order for a realistic assessment of risk to be carried out. However, engines such as QRisk2 and the JBS3 calculator (http://www.jbs3risk.com/pages/risk_calculator.htm) only require the TC:HDL ratio and/or non HDL-C value to be entered. This is in recognition of the role that these two key measurements play in cardiovascular risk. So does that mean that we only ever need to measure these two levels?

The NICE3 guideline on cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification, offers advice on this point. It suggests that a full fasting lipid profile can be done initially to identify any anomalies in each of the individual components of the lipid profile but that subsequently only the non-fasting TC and HDL-C need to be measured. This is because the factor that is now targeted when treating dyslipidaemia is the non HDL-C value. Previously, in primary prevention, there were no recommended targets and simply being on a statin was considered to be enough to benefit the patient: the so-called ‘fire and forget’ approach. Specific targets for TC and LDL-C which were previously suggested for secondary prevention and diabetes (i.e. TC of 4mmol/l or less and/or LDL-C of 2mmol/l or less) are no longer used to assess the impact of treatment. Instead the current approach is to reduce non HDL-C by 40% or more.

THE MATHS BIT

Deidre, age 57, attended for an NHS health check and was found to have a QRisk2 risk score of 18%. After discussing the benefits of lifestyle interventions to reduce her overall risk, she was also keen to start on lipid lowering therapy. Her lipid profile showed a TC of 6.7mmol/l, an HDL-C of 1.2mmol/l and triglycerides of 2.2mmol/l. Her non HDL-C is therefore 6.7-1.2 = 5.5. To work out what 60% of Deidre’s non HDL-C is (in other words, identifying our target level if we reduce it by 40%) we need to do this calculation:

60/100 x 5.5 = 3.3

So the aim of treating Deidre’s lipid levels is to reduce her pre-treatment non HDL-C from 5.5mmol/l to 3.3mmol/l or lower.

TREATING DYSLIPIDAEMIA

Before starting on treatment, known causes of dyslipidaemia should be excluded. These include diabetes (especially undiagnosed or poorly controlled diabetes), hypothyroidism, liver disease and nephrotic syndrome. When these have been excluded through baseline bloods (fasting glucose or HbA1c, renal and liver function, thyroid function tests) the pros and cons of lipid lowering therapy should be discussed with the patient, allowing time for them to express their views and address any concerns that they may have.6 Once the decision to treat has been made, NICE recommends the use of a high intensity low cost statin as the most cost effective way of improving the lipid profile.7 In primary prevention this is most likely to be atorvastatin 20mg. Statin therapy is not recommended in women of childbearing age or who are breastfeeding. Other high intensity statins include atorvastatin 40mg and 80mg, simvastatin 80mg and rosuvastatin 10mg, 20mg and 40mg. In secondary prevention (i.e. for those patients who have already had a cardiovascular event) atorvastatin 80mg is recommended in the NICE guidelines. However, it is important to remember that statin side effects occur most frequently at higher doses and not everyone will be able to tolerate this dose. This is where a better option may be to use a lower dose of atorvastatin along with ezetimibe.

Ezetimibe

Ezetimibe has recently been the subject of an updated technology appraisal (TA) from NICE based on recent outcomes data from the IMPROVE-IT study.8,9 Ezetimibe acts as a cholesterol absorption inhibitor. Most of the cholesterol in the circulation is made by the liver and transported to the intestine. Ezetimibe acts in the intestine to block the absorption of cholesterol produced both by the liver and from dietary sources and this action complements that of a statin, which acts on the liver to reduce production of cholesterol. Ezetimibe can also be used as monotherapy in people who are statin intolerant.3 The new TA from NICE reiterates previous advice that ezetimibe is a useful lipid lowering therapy. However, its position has been further strengthened by the publication of the IMPROVE IT study,9 which confirmed that ezetimibe can reduce the risk of cardiovascular events – the outcomes data that had previously been missing. The study was a large (over 18,000 patients) randomised controlled trial looking at high risk patients who had a history of acute coronary syndrome, some of whom who were already being treated with a statin and all of whom already had acceptable LDL-C levels. Trial participants were given either simvastatin alone or simvastatin with ezetimibe. After 6-7 years there was a 6.4% relative risk reduction in cardiovascular events in the group treated with simvastatin and ezetimibe compared with those treated with simvastatin alone. LDL-C was reduced by 0.43mmol/l more after a year on dual therapy compared with simvastatin alone. Furthermore, the study confirmed no safety concerns with the drug. The TA from NICE means that ezetimibe must now be funded by clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) for patients who would benefit from this treatment.

FAMILIAL HYPERCHOLESTEROLAEMIA (FH)

FH is caused by a genetic anomaly that causes inherently high levels of cholesterol leading to premature cardiovascular death. The defect is hereditary, so affected families will often have several members who have suffered from early cardiac events or deaths. FH should be suspected in anyone with a TC of 7.5mmol/l or more, particularly if there is a family history of premature CHD. The QRisk algorithm is not suitable for assessing risk in suspected FH and the Simon Broome assessment tool should be used for initial diagnostic purposes instead, followed by referral for DNA testing and cascade testing of family members.10,11

The aim of treatment in FH is different from that is non-familial dyslipidaemia. Rather than aiming to reduce HDL-C by 40%, the focus in FH is on LDL-C. The target is to reduce LDL-C by 50% or more.12 High intensity statins at high doses may be used to treat FH along with ezetimibe, which can also be used first line if statins are not tolerated. Other less conventional therapies may also be indicated because of the high risk of early CHD. These include bile acid sequestrants, fibrates or nicotinic acid, none of which are considered to be useful in managing non-familial dyslipidaemias. The use of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors may also be indicated, although these drugs do not have NICE authorisation at this stage. Both of the PCSK9 inhibitor therapies currently available exceed the cost ceiling of £20-30,000 per quality adjusted life year (QALY) set by NICE, and NICE considers that a statin and ezetimibe could potentially offer a more cost effective option for treating FH. NICE was also concerned about the lack of CVD outcomes data for these novel drugs.

MONITORING PEOPLE ON STATIN THERAPY

NICE recommends that anyone on statin therapy should have liver function tests (LFTs) checked before and 3 months after starting on treatment. The non-HDL cholesterol value should also be measured at 3 months to assess response and whether treatment should be intensified – either by increasing the statin dose or by adding in ezetimibe – should be considered. Further assessment of LFTs and the non HDL-C should be carried out at a year. NICE then states that there is no need to recheck the LFTs, although an annual non HDL-C reading should be recorded. Abnormal LFTs should not be deemed a barrier to introducing a statin unless the transaminases (ALT and AST) are more than three times the upper limit of normal.3 However, consideration should be given to the reason for this increase as there may be links to obesity, diabetes and excess alcohol intake, all of which can affect the liver and the lipid levels.13

LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS

Lifestyle interventions such as eating a low sugar diet, reducing alcohol intake, stopping smoking, losing weight and taking more exercise can all help to improve the lipid profile and reduce cardiovascular risk.14 Patients and health care professionals should be aware that any medication should be used to complement these changes and that drug therapy is not a substitute for them.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the decision to start treatment for dyslipidaemia is based on an individual’s cardiovascular risk score unless they are already in a high risk group. These include most people with type 1 diabetes, people with FH, those who have already had a cardiac event and those with chronic kidney disease. People over 85 are also considered to be automatically at high risk but consideration should be given to each case before starting statin therapy. Statin therapy is not recommended in women of childbearing age or who are breastfeeding. For people who are on lipid lowering therapy to improve their cardiovascular risk profile, the aim is to reduce non HDL-C by 40% or more using a low cost, high intensity statin. General practice nurses have a role to play in identifying people at risk who might need statin therapy and offering on-going support and monitoring to ensure they obtain the optimal benefit from treatment and lifestyle changes.

REFERENCES

1. Yusuf S et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 2004 364(9438):937-52.

2. Heart UK. What is cholesterol? 2016 https://heartuk.org.uk/health-and-high-cholesterol

3. NICE CG181. Guidelines on Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification, 2014 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181

4. NHS Choices. Diagnosing high cholesterol, 2015 http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Cholesterol/Pages/Diagnosis.aspx

5. American Heart Association. Good vs bad cholesterol, 2014 http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/Cholesterol/AboutCholesterol/Good-vs-Bad-Cholesterol_UCM_305561_Article.jsp#.VvrjI74rLIU

6. NICE NG5. Medicines optimisation, 2015 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5

7. NICE QS100. Quality Standard: Cardiovascular risk assessment and lipid modification, 2015 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs100

8. NICE TA385. Ezetimibe Technology Appraisal, 2016 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA385

9. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT) N Engl J Med 2015;372:2387-2397

10. NICE CG71. Familial hypercholesterolaemia, 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg71

11. NICE. Familial hypercholesterolaemia – Simon Broome criteria, 2016. http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/familial-hypercholesterolaemia#path=view%3A/pathways/familial-hypercholesterolaemia/diagnosing-familial-hypercholesterolaemia.xml&content=view-node%3Anodes-provisional-clinical-diagnosis

12. NICE QS41. Quality Standard: Familial Hypercholesterolaemia, 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/QS41

13. British Liver Trust. Non alcohol related fatty liver disease, 2012 http://www.britishlivertrust.org.uk/liver-information/liver-conditions/non-alcohol-related-fatty-liver-disease/

14. Viljoen A. Improving dyslipidaemia management: focus on lifestyle intervention and adherence Br J Cardiol 2012;19(Suppl 1):s1-s16

Related articles

View all Articles