Lipid management for primary care

Beverley Bostock RGN MSc MA QN Advanced Nurse Practitioner,Mann Cottage Surgery, Gloucestershire Cou...

Beverley Bostock RGN MSc MA QN Advanced Nurse Practitioner,Mann Cottage Surgery, Gloucestershire Council Member, Primary Care Cardiovascular Society

Practice Nurse 2023;53(4):16-19

Time was, the only drugs available for lipid lowering were the statins – but now there are many options available, both for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. So which drug should be used and when?

Lipid management is a key part of the management of several long-term conditions including coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. It is also an important component of the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Despite this, many clinicians find it hard to know which interventions should be implemented when and for whom. This article takes a case study-based approach to the management of dyslipidaemia in cardiovascular risk reduction, in order to illustrate these points.

By the end of this article, readers should be able to:

- Recognise the different lipid fractions and the part they play in the development of cardiovascular disease

- Reflect on the use of pharmacotherapy in reducing cardiovascular risk

- Analyse the options in statin intolerance

- Examine the role of injectable therapies

- Consider national and international recommendations on lipid targets

LIPID FRACTIONS AND CVD

A full lipid profile includes total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and triglycerides. Previously, fasting blood tests were recommended, but this is no longer the case. It was felt that the impact of fasting on lipid levels (and it is only triglycerides which are directly affected) was so small as to be irrelevant when compared to the value of people being able to have bloods taken at any time of the day.1,2

HDL-C is generally considered to be ‘good’ cholesterol, because it works as part of a reverse cholesterol transport system, removing cholesterol from tissues and returning it to the liver for recycling. HDL-C also has important antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. The HEART UK resources for healthcare professionals can be useful in understanding this and explaining it to patients. They can be accessed here.

The ratio of TC to HDL-C will be used to calculate cardiovascular (CV) risk in tools such as QRisk. For example, if the TC is 6mmol/L and the HDL-C is 1mmol/L, the TC: HDL-C ratio will be 6÷1, which is 6mmol/L. This value will be entered into the QRisk calculation as part of the cardiovascular risk assessment. This is, in fact, the only time that the ratio is used. However, non-HDL-C values are routinely used to determine whether lipid lowering therapy has been successful. To calculate the non-HDL-C value, the HDL-C is subtracted from the TC. So, if the TC is 6mmol/L and the HDL-C is 1mmol/L, the non-HDL-C will be 6.0 – 1.0, which is 5mmol/L.

Often a low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) value will also be reported as part of the lipid profile, and this is the atherogenic cholesterol which furs up the arteries and is a key component in the development of cardiovascular disease. If the local laboratory does not routinely report LDL-C levels, these can be calculated using the TC, HDL-C and triglyceride values, via the MDcalc tool.

Triglycerides are made up of fatty acids and glycerol and are an energy source which comes from food and from the liver’s own supply. Risk factors for raised triglycerides include obesity, increased sugar or alcohol consumption, and type 2 diabetes.3 People with raised triglycerides often have a low HDL-C, too, increasing their risk of CVD on two levels.4

It is important to note that there is a link between thyroid dysfunction and dyslipidaemia. NICE recommends that thyroid function tests should be considered in people with dyslipidaemia, especially before considering a referral.5 Other causes of dyslipidaemia should also be considered including excess alcohol intake, undiagnosed or poorly controlled diabetes, liver disease and nephrotic syndrome.

TARGETS

In the UK, non-HDL-C levels are often used to determine whether lipid lowering targets have been reached; internationally, both non-HDL-C and LDL-C are used as target values. The current Accelerated Access Collaborative (AAC) guidance and NICE both recommend using non-HDL cholesterol as the target value when treating lipids.2,5 According to the AAC recommendations, once the decision has been made to start lipid lowering medication, a full non-fasting lipid profile should be measured after three months with the aim of reducing non-HDL-C by 40%. However, this target has many critics, who point out that in people with a high starting point, a 40% reduction may still not be enough. The Primary Care Cardiovascular Society takes the view that an absolute non-HDL-C value of 2.5mmol/L or lower is preferable. A non-HDL-C of 2.5mmol/L is equivalent to an LDL-C of 1.8mmol/L. The non-HDL-C value is the key target for secondary prevention in the Quality Outcomes Framework, again with a recommendation to aim for a value of 2.5mmol/L or lower.

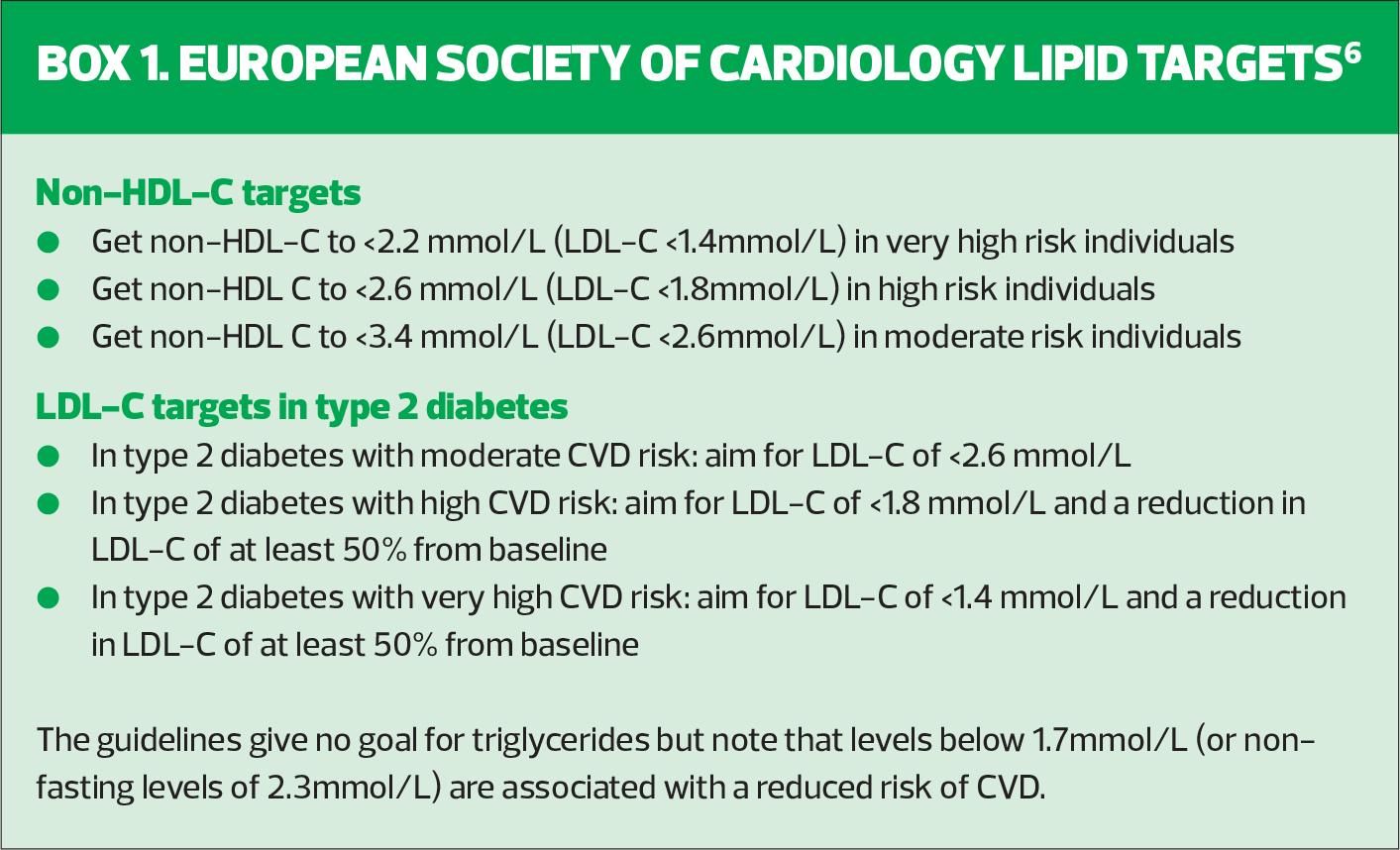

However, international guidelines take a more nuanced view of target values. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has recommendations for people with established cardiovascular disease or diabetes based on their level of risk.6 These recommendations state that the clinician should establish the level of risk (very high, high, moderate or low) through their current presentation and history and/or the European SCORE CVD risk assessment tools, which can be accessed here. The criteria for each category are explained in detail in the guidelines, but in essence people with established CVD or chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 4, and people with diabetes with microvascular complications or diabetes with three other risk factors would be included in the very high-risk category. High risk would include people with diabetes without microvascular complications or those with CKD stage 3a or 3b. Moderate risk would apply to younger people with diabetes – below the age of 35 in type 1 and below 50 in type 2. Once the level of risk has been calculated, the targets would be set – see Box 1.

LIPID LOWERING FOR PRIMARY PREVENTION

Let’s consider the case of Jay, aged 64 years. Jay is new to the practice and has a history of hypertension treated with amlodipine and an ACE inhibitor and his blood pressure (BP) is now at target. The general practice nurse (GPN) reviews him and realises that his QRisk score is over 10%, indicating that a statin is recommended for CV risk reduction. Currently Jay’s TC is 6.1mmol/L, his HDL-C is 1.1mmol/L and his non-HDL-C is 5.0mmol/L. His triglycerides are raised at 2.5mmol/L and his LDL-C has been calculated (using the MdCalc website) at 4.8mmol/L.

Jay is being treated on the basis of his QRisk score being 10% or more. As he is a primary prevention case, the GPN will discuss lifestyle advice and following discussion (and some myth-busting) about statins, she recommends atorvastatin 20mg. A full non-fasting lipid profile will be repeated in 3 months’ time.

When Jay’s lipids are repeated, the non-HDL-C is now down to 2.9mmol/L. Although this is an excellent result, additional therapy would be advised after checking for adherence.

The use of additional lipid-lowering therapies

The first step to improving Jay’s lipid profile would be to increase the dose of the statin. After 3 months on atorvastatin 40mg, the lipid profile should be repeated. If Jay was still not at target, 80mg might be considered. However, higher doses of statins may be associated with an increased risk of side effects and if this is the case for Jay, alternative therapies can be offered to add into a lower dose of statin. These include ezetimibe and bempedoic acid.

Ezetimibe is a non-statin lipid-lowering therapy which can effectively reduce LDL-C when taken with a statin.7 It is usually well tolerated with few side effects, although gastrointestinal symptoms have been reported. It is prescribed at a dose of 10mg.

Bempedoic acid is a newer therapy which can be prescribed alone or in combination with a statin and/or ezetimibe. NICE has recommended bempedoic acid primarily for statin intolerance but there is evidence to show that it is effective when used with a statin.8,9

STATINS IN SECONDARY PREVENTION

Joseph aged 55 years, was a lifelong heavy smoker until he was diagnosed with peripheral arterial disease 3 years ago. Following his diagnosis, he quit smoking. As someone with established cardiovascular disease he was treated with atorvastatin 80mg. His latest lipid profile is reported as a TC of 3.1mmol/L, an HDL-C of 1.3mmol/L, a non-HDL-C of 1.9mmol/L, triglycerides of 1.5mmol/L and an LDL-C of 1.1mmol/L. Joseph’s lipid profile indicates that he is treated to target.

Karolina, aged 63 years, had a myocardial infarction two years ago and was also treated with atorvastatin at the secondary prevention dose of 80mg. However, she developed sleep disturbance and headaches so she stopped it. After discussing this with her GPN, she was restarted on 20mg atorvastatin which was subsequently increased to 40mg. She tolerated this well but was unable to get back to 80mg because of myalgia at that dose. Karolina’s latest lipid profile is not at target. Her TC is 4.3 mmol/L, her HDL-C is 0.8 mmol/L, the non-HDL-C is 3.5 mmol/L, her triglycerides are 2.6 mmol/L and her LDL-C is 2.3 mmol/L.

At this stage, the clinician could consider the addition of ezetimibe and/or bempedoic acid to get Karolina to target. As Karolina’s LDL-C is at target, but her triglycerides remained raised, she would also qualify for icosapent ethyl (Vazkepa) which is licensed for secondary prevention, or for people with diabetes plus another CV risk factor. NICE recommends icosapent ethyl for secondary prevention to reduce residual CVD risk in people who are already taking statins but whose LDL-C is between 1.04 mmol/L and 2.6 mmol/L and where triglycerides remain raised at 1.7 mmol/L or above.10 The medication comes as a single 998mg dose, taken as two capsules, twice daily with food. Karolina would also qualify for inclisiran (see below).

Harry, aged 68 years, has type 2 diabetes and had a myocardial infarction last year. He’s on a range of secondary prevention medication including atorvastatin 80mg. His latest lipid profile shows that he has a TC of 4.9mmol/L, an HDL-C of 1.0 mmol/L, a non-HDL-C of 3.9 mmol/L, triglycerides of 1.7 mmol/L and an LDL-C of 3.1 mmol/L indicating that he is not at target. As Harry is already on the maximum dose of a statin, along with the other therapies mentioned above, he could also be considered for the injectable therapy, inclisiran.

INJECTABLE THERAPIES

Inclisiran is a lipid-lowering injectable medication, which uses RNA interference to increase the number of LDL-C receptors and the hepatic uptake of LDL-C to reduce LDL-C by around 50%.11 NICE has approved inclisiran for use in secondary prevention, where the lipids are not controlled (LDL-C of 2.6mol/L or higher) with the medications mentioned above.12 Inclisiran can also be used in people who have been unable to tolerate statins or other drugs. It can be initiated and prescribed in primary care, and once it has been initiated, a repeat dose is given at 3 months. From then on, the dose is given 6-monthly. Side effects are rare and are generally limited to injection site tenderness.

PCSK9 inhibitors are injectable therapies which are initiated in secondary care for people who have a history of CVD and who are unable to get to target with the medications mentioned above. They are also licensed for familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) which is managed by specialist lipidologists.

LIPID LOWERING IN OLDER PEOPLE

Mabel is a frail 83-year-old lady who has a history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and osteoarthritis. She also has mild cognitive impairment. Her latest blood results show that her diabetes is well controlled with an HbA1c of 55mmol/mol and her lipid profile shows that she has a total cholesterol 3.7mmol/L and an HDL-C of 1.2mmol/L, giving her a non-HDL-C of 2.5mmol/L. Her eGFR is 52ml/min and has been stable in the 50s over the past 18 months. Her blood pressure is acceptable at 135/72mm Hg and she has no postural drop. During a medication review, where the focus is on deprescribing, Mabel’s son asks whether her statin should be stopped. The GPN explains that Mabel’s CVD risk score and her CKD are both indications for a statin and that her lipids are currently at target. Mabel has suffered no side effects from taking her statin, so there is a shared agreement to continue with this medication. The ESC Dyslipidaemia Guidelines support the use of statins in high-risk people aged 75 and over with the proviso that lower starting doses and gentle uptitration may be needed.6

THE IMPACT OF LIPID-LOWERING MEDICATION

The AAC has a table that demonstrates the average lipid lowering effect of different therapies.2 As a general rule, low intensity statins will produce an LDL-C reduction of 20-30%, medium intensity statins will produce an LDL-C reduction of 31-40% and high intensity statins will produce an LDL-C reduction above 40%. Ezetimibe combined with any statin will potentially result in a greater reduction in non-HDL-C or LDL-C than doubling the dose of the statin. Bempedoic acid when combined with ezetimibe produces an additional LDL-C reduction of approximately 28%. Inclisiran alone or in combination with statins or ezetimibe produces an additional LDL-C reduction of approximately 50% but no clinical outcomes are currently available. PCSK9 inhibitors alone or in combination with statins or ezetimibe produce an additional LDL-C reduction of approximately 50%.

- Find further information on the drugs mentioned above, including prescribing advice on side effects and contraindications, at the Electronic Medicines Compendium

SUMMARY

The different lipid fractions (TC, HDL-C, LDL-C and triglycerides) play different roles in CVD risk. The TC: HDL-C ratio is used to assess risk using tools such as QRisk, whereas the non-HDL-C or LDL-C is used for optimising lipid-lowering therapies in order to reduce CVD risk. There is a range of drugs which can be used to this effect, along with lifestyle modification. Statins are the first-line pharmacological intervention, but ezetimibe, bempedoic acid, icosapent ethyl, inclisiran and PCSK9 inhibitors can all play their part in reducing LDL-C, even in those patients who cannot tolerate statins. In clinical practice it is important to recognise which drugs are indicated in which circumstances to ensure that care is individualised and opportunities to reach target lipid levels are optimised.

REFERENCES

1. Mora S, Chang CL, Moorthy MV, Sever PS. Association of non-fasting vs fasting lipid levels with risk of major coronary events in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial – Lipid Lowering Arm. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179(7):898–905

2. NHS England/Accelerated Access Collaborative. National guidance for lipid management; 2022 https://www.england.nhs.uk/aac/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2020/04/National-Guidance-for-Lipid-Management-Prevention-Dec-2022.pdf

3. Sweeney MET. Hypertriglyceridemia; 2021 https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/126568-overview

4. Bazarbashi N, Miller M. Triglycerides: how to manage patients with elevated triglycerides and when to refer?. Med Clin N Am 2022;106(2):299–312.

5. NICE CG181. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification; 2016, updated 2023 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181

6. European Society of Cardiology. 2019 Guidelines on Dyslipidaemias (Management of) ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines; 2019 https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Dyslipidaemias-Management-of

7. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al, for the IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2015;372(25):2387–2397

8. NICE TA694. Bempedoic acid with ezetimibe for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia; 2021 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta694

9. Ballantyne CM, Bays H, Catapano AL, et al. Role of bempedoic acid in clinical practice. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2021;35:853–864

10. NICE TA805. Icosapent ethyl with statin therapy for reducing the risk of cardiovascular events in people with raised triglycerides; 2022 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta805

11. Ray KK, Kallend D, Leiter L A, et al, for the ORION-11 Investigators. Effect of inclisiran on lipids in primary prevention: the ORION-11 trial. Eur Heart J 2022;43(48):5047–5057

12. NICE TA733. Inclisiran for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia; 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta733

Related articles

View all Articles