CVD in women: overlooked, underdetected, and undertreated

Meredith Donaldson, MSc (Physician Assistant Studies), MSc (Long-term Conditions), PhD Candidate Primary Care Cardiovascular Society (PCCS) Council Member

Practice Nurse 2026;56(1):13-17

Women are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than from breast cancer, for example, but frequently experience delays in detection and diagnosis, and less than optimal treatment: so what can clinicians do to close the gender gap?

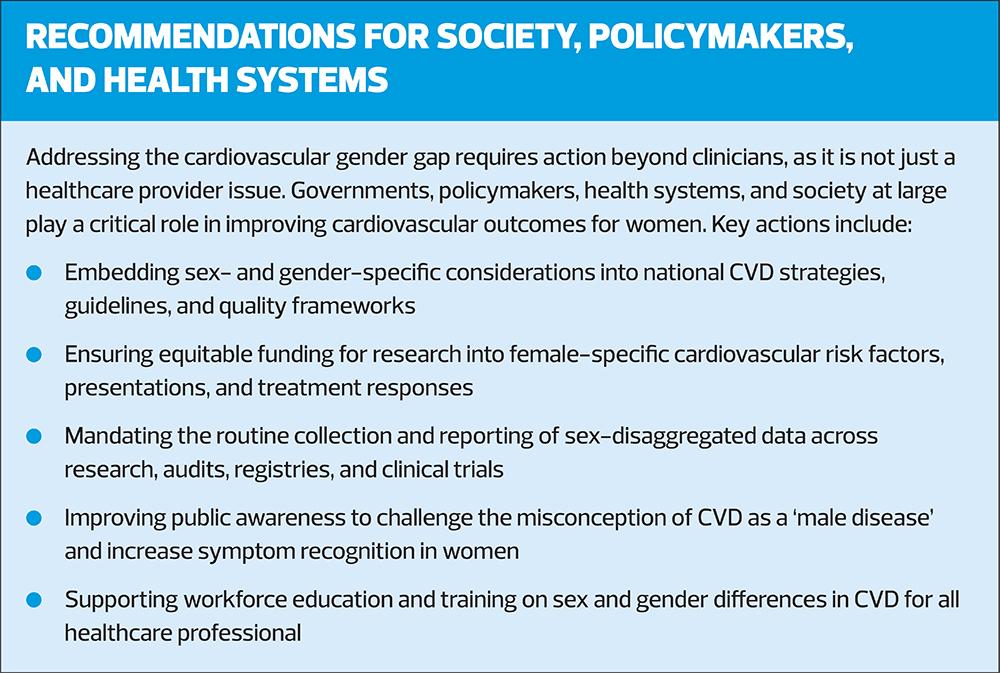

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death globally for both men and women.1 In the UK, women are more likely to die from CVD than from breast cancer, lung cancer, and chronic respiratory disease combined.2 Despite these figures, CVD continues to be perceived, by both patients and healthcare providers, as primarily affecting men. This misconception has contributed to significant delays in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment for women.1

Women experience poorer outcomes across multiple cardiovascular conditions. Compared with men, women experience delays in diagnosis, treatment, and revascularisation for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).3 They are less likely to be referred for diagnostic assessment of coronary artery disease (CAD) and, following myocardial infarction (MI), have longer hospital stays and higher 12-month mortality. Women are also less likely to receive guideline-directed medical therapies (GDMT) such as antiplatelets and statins, and are less likely to achieve optimal CVD risk factor targets such as LDL-cholesterol, blood pressure, and HbA1c.1

One explanation for the delays in diagnosis is that women may present with atypical symptoms when experiencing a CVD event. For example, men have a more classical presentation of an MI with central crushing chest pain that may radiate to the left arm or jaw. Meanwhile, women more commonly report breathlessness, epigastric pain, palpitations, nausea, fatigue, dizziness, or back and shoulder pain. These ‘atypical’ symptoms are frequently misattributed to gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or psychological causes, leading to missed or delayed diagnoses.3

Healthcare provider bias also contributes to disparities. Studies have shown that women treated by male physicians have worse outcomes and higher mortality than those treated by female physicians. However, this disparity can be mitigated when male clinicians have greater experience caring for female patients or if they work alongside female colleagues.3

It is also important to note that traditional CVD risk factors impact women differently, and women have sex-specific risk factors during their lifespan, which may not be accounted for, particularly when using traditional CVD risk score calculators, such as QRISK3.1,4

TRADITIONAL CVD RISK FACTORS AND HOW THEY DIFFER IN WOMEN

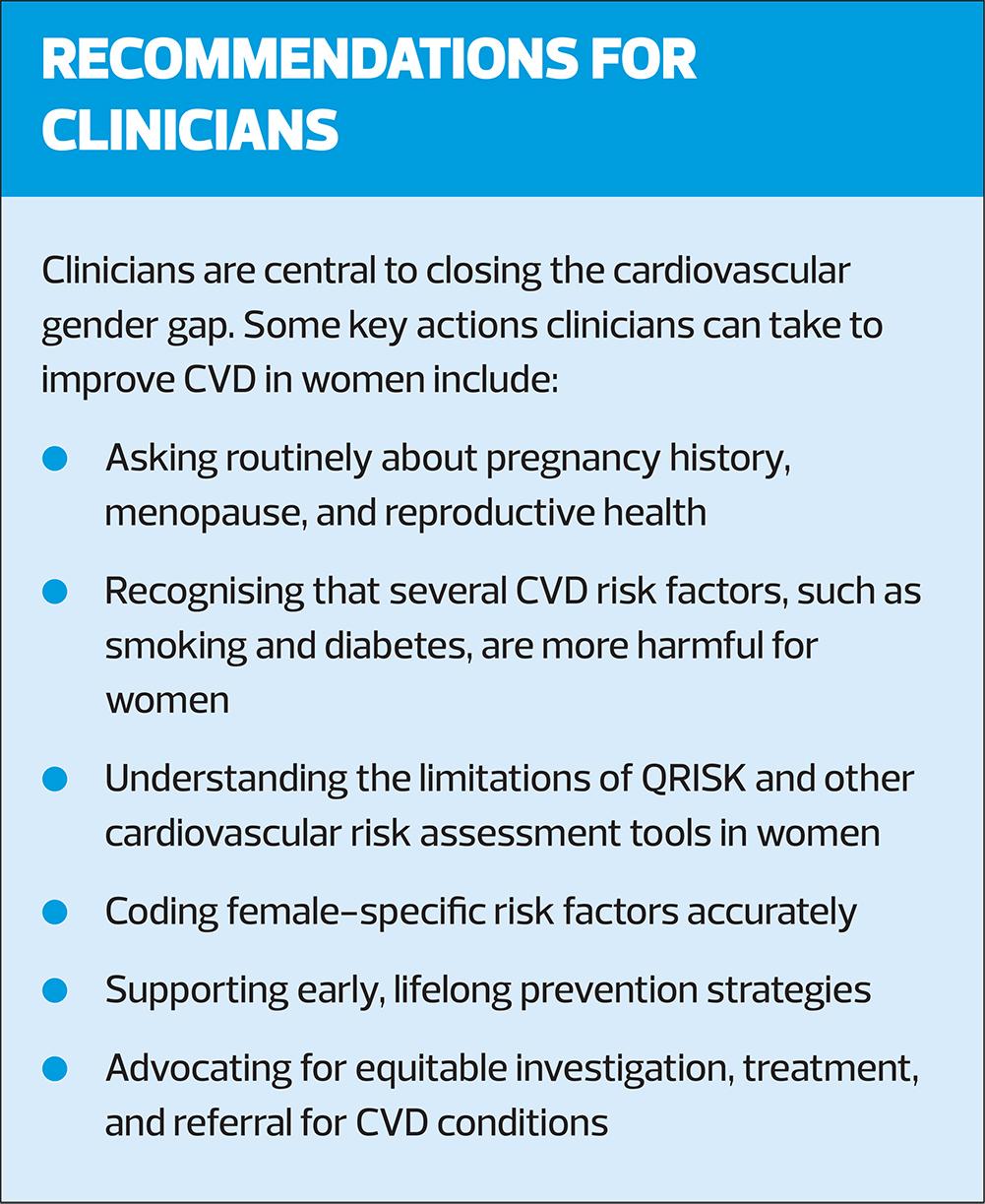

Many traditional cardiovascular risk factors affect both sexes, but for some risk factors, their impact is often more pronounced or harmful in women. By recognising these differences, clinicians can identify CVD risk factors earlier, ensuring they are accurately coded and addressed to improve long-term CVD prevention.1

Obesity

Obesity is the only traditional risk factor discussed in this article that is more common in women (30%) than in men (28%) in England. However, there is a significantly higher CVD risk attributed to obesity in women than there is for men, as shown in the Framingham Study.1

Smoking

Smoking remains one of the most significant sex-specific differences. Smoking prevalence is higher in men, being 19% in the male population, versus 15% of women in England in 2012–2017. However, women who smoke experience a 25% greater excess risk of CAD compared with male smokers, particularly in younger age groups.1 The risks of CVD (including venous thromboembolism (VTE)) in women who smoke are compounded further by hormonal treatments, including the combined oral contraceptive pill and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) containing oral oestrogen.4

Diabetes

Diabetes is more common in men (9% vs 6%), yet its cardiovascular consequences are substantially worse in women. Diabetes increases a woman’s risk of fatal CAD by approximately 50% more than in men.1 Women with diabetes are also less likely to achieve optimal control of blood pressure and LDL-cholesterol, in part due to undertreatment, compounding long-term risk.4

Hypertension

Hypertension is more common in men at a younger age (27% vs 24%) and becomes more prevalent in women after menopause. While younger women generally have lower blood pressure than men due to the vasodilatory effects of oestrogen, this advantage is lost after menopause, after which women rapidly surpass men in rates of hypertension and its complications.1,4

Dyslipidaemia

Dyslipidaemia is also influenced by oestrogen. Men are more likely to have dyslipidaemia than women in the UK (52% versus 46%). However, after menopause, women experience a rise in LDL-cholesterol and triglycerides alongside a reduction in HDL-cholesterol, contributing to accelerated atherosclerosis.4

SEX-SPECIFIC RISK FACTORS THROUGHOUT A WOMAN’S LIFESPAN

In addition to traditional risk factors, women experience several sex-specific risk factors throughout the lifespan that may not be accounted for in most cardiovascular risk assessment tools.

Pregnancy-related CVD risk factors

Pregnancy is increasingly recognised as a ‘natural cardiovascular stress test,’ unmasking underlying CVD vulnerability that may not have otherwise become clinically apparent for many years. Adverse pregnancy outcomes are now known to significantly increase future cardiovascular risk.5

Pre-eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia has one of the strongest associations with CVD. Women with a history of pre-eclampsia have a fourfold increased risk of heart failure and approximately double the risk of CAD, stroke, and cardiovascular death later in life.6 Despite this, pre-eclampsia is under-recorded in primary care records in the UK, and there is no recommended standard CVD monitoring after delivery.7 Pre-eclampsia is included in the upcoming QRISK4; however, gestational diabetes is currently not.8

Gestational diabetes

Gestational diabetes has significant associations with increased metabolic and cardiovascular risk, even in women who do not go on to develop type 2 diabetes later in life. It increases the risk of CAD and heart failure by 45% and doubles the risk of myocardial infarction.9 These women benefit from early lifestyle intervention, regular metabolic surveillance, and proactive cardiovascular risk management.

Other pregnancy-related factors

Other pregnancy-related factors associated with increased cardiovascular risk include gestational hypertension, infertility, miscarriage, stillbirth, premature delivery, and intrauterine growth restriction.10

Clinicians should improve coding of these pregnancy-related risk factors by identifying and addressing them during health checks, chronic condition reviews, pill reviews, and menopause reviews.

REPRODUCTIVE-RELATED RISK FACTORS

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) affects up to 10% of women and increases cardiovascular risk by approximately 30%, largely through its association with insulin resistance, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and type 2 diabetes.1,11 PCOS is not included in most cardiovascular risk calculators, meaning risk may be underestimated unless clinicians explicitly account for it.10

Premature menopause, which is classed as menopause occurring before the age of 40, is associated with significantly increased cardiovascular risk. Loss of oestrogen at a younger age leads to earlier onset (and longer duration) of CVD factors experienced during menopause, which can include excess risk of hypertension, dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction.11

Menopause: even menopause occurring within the typical time frame represents a significant increase in cardiovascular risk. As oestrogen levels fall, women experience:

- Rising LDL-cholesterol

- Increased blood pressure

- Central adiposity

- Increased insulin resistance

These changes impact CVD risk so significantly that postmenopausal women have two– to six-times greater risk of CVD than premenopausal women.4

Vasomotor symptoms such as hot flushes and night sweats are independently associated with a 50–77% increased risk of cardiovascular disease, even when adjusting for endogenous estradiol concentrations. These symptoms correlate with higher blood pressure, dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, and symptoms may persist for 7–9 years.12 This highlights the importance of recognising menopausal symptoms as potential cardiovascular risk markers.

To help with vasomotor symptoms, women often choose HRT. It is now known that HRT, when initiated within 10 years of menopause or before age 60, may reduce cardiovascular risk, although its role in primary prevention requires further study.13 It is also important to note that different types of HRT confer different CVD risks.

Oestrogen

Oral oestrogen has 2x the risk of VTE compared with patients receiving no HRT and increases the risk of stroke. Oral oestrogen undergoes first-pass hepatic metabolism, thereby increasing clotting factors, CRP, and triglycerides, and subsequently increasing thrombotic risk. If oral oestrogen is used, estradiol (E2) has a lower risk of VTE than conjugated equine oestrogens (CEE). Transdermal oestrogen bypasses the liver and consequently does not increase the risk of VTE, does not have an increased risk of stroke, and has a neutral impact on lipids. Therefore, transdermal oestrogen is preferred for women who are at an increased risk of CVD.14

Progesterone

Micronised progesterone (which is bioidentical to endogenous progesterone) does not increase the risk of VTE. In contrast, most synthetic progesterones, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethisterone, increase the risk of VTE and stroke. However, dydrogesterone is synthetic but structurally similar to progesterone, acts similarly to endogenous progesterone, and therefore does not increase VTE risk. Hence, micronised progesterone and dydrogesterone are recommended over synthetic progesterones for women at increased risk of CVD.14

QRISK4

NICE (NG238) recommends routine cardiovascular risk assessment using QRISK3 (where available) for adults aged 25–84 years,15 but QRISK4 has improved its recognition of sex-specific CVD risk with the inclusion of:

- Pre-eclampsia

- Postnatal depression

However, QRISK4 still does not include several sex-specific risk factors, including:

- Gestational diabetes

- PCOS

- Premature menopause

- Infertility

- Early or late menarche

- Use of the combined oral contraceptive pill

As a result, QRISK4 is likely to underestimate cardiovascular risk in women, particularly younger women and those with adverse pregnancy outcomes.8,10 NICE (NG238) guidance acknowledges the importance of clinical judgement in such cases, and clinicians should consider earlier intervention and closer monitoring where female-specific risks are present, even when QRISK scores appear low.15

Accurate coding of pregnancy complications and reproductive history is therefore essential to improving long-term cardiovascular prevention.

SPECIFIC CVD CONDITIONS IN WOMEN

Coronary artery disease

Women are less likely to be referred for investigation of suspected CAD and are more likely to experience in-hospital complications, cardiogenic shock, and higher 12-month mortality following acute coronary syndromes.1

Anatomical and pathological differences can contribute to adverse outcomes. Women tend to have smaller coronary vessels and more diffuse atherosclerotic disease affecting multiple small vessels, rather than large focal plaques seen more commonly in men. This explains why women may continue to experience angina after stenting and why microvascular disease is more prevalent. However, microvascular disease is often not appreciated by clinicians and microvascular resistance is frequently not measured.11 Women are therefore more likely to experience angina or myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive CAD, known as ischaemia, angina, or MI with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA, ANOCA, or MINOCA), frequently due to coronary microvascular dysfunction.1

Heart failure

Heart failure is frequently under-recognised in women. Women often present at an older age, with more comorbidities, and experience delays in diagnosis and referral. Normal left ventricular ejection fraction is generally higher in women (60–65%) than in men, yet guideline thresholds do not account for this, potentially delaying diagnosis.1

Women with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) are less likely to receive GDMT, despite evidence that they may derive greater benefit from certain treatments such as sacubitril-valsartan and spironolactone.11

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is more common in women than men and is frequently associated with ageing as well as comorbidities such as hypertension, obesity and diabetes. Women with HFpEF are more likely to present acutely and experience delays in cardiology referrals.1 Interestingly, despite these disparities, women in the European Society of Heart Failure (ESC) Heart Failure Long-Term Registry demonstrated better one-year survival than men.16

Heart Valve Disease

While the overall prevalence of valve heart disease is similar between men and women, mitral valve disease and aortic stenosis are more common in women. Women are also less frequently referred for valve interventions and are typically referred later in the disease course, resulting in poorer outcomes.1,11 Smaller heart size and reliance on male-based diagnostic thresholds may contribute to underestimating disease severity in women.1

Arrhythmias

Differences between men and women can be seen on ECG. Women tend to have narrower QRS complexes and slower resting heart rates. Premenopausal women have longer QT intervals, increasing the risk of drug-induced arrhythmias. Although anticoagulation is equally effective in women and men with atrial fibrillation, women are less likely to receive anticoagulants or rhythm-control therapies and are less likely to be referred for catheter ablation, despite reporting more severe symptoms and poorer quality of life.1,11

Autoimmune disease and inflammation

Women are more likely to have autoimmune diseases, which increase systemic inflammation and accelerates atherosclerosis. Long-term steroid therapy further compounds cardiovascular risk by increasing blood pressure, glucose levels, and dyslipidaemia.11

Takostubo

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, also known as ‘broken heart syndrome’ is often triggered by emotional or physical stress and affects women in 80–90% of cases, with most occurring in postmenopausal women over the age of 50. It was previously thought to be benign, but it is now recognised as a condition associated with significant morbidity and mortality. One in ten people will suffer at least one further Takutsobo event after the initial recovery.17

SUMMARY

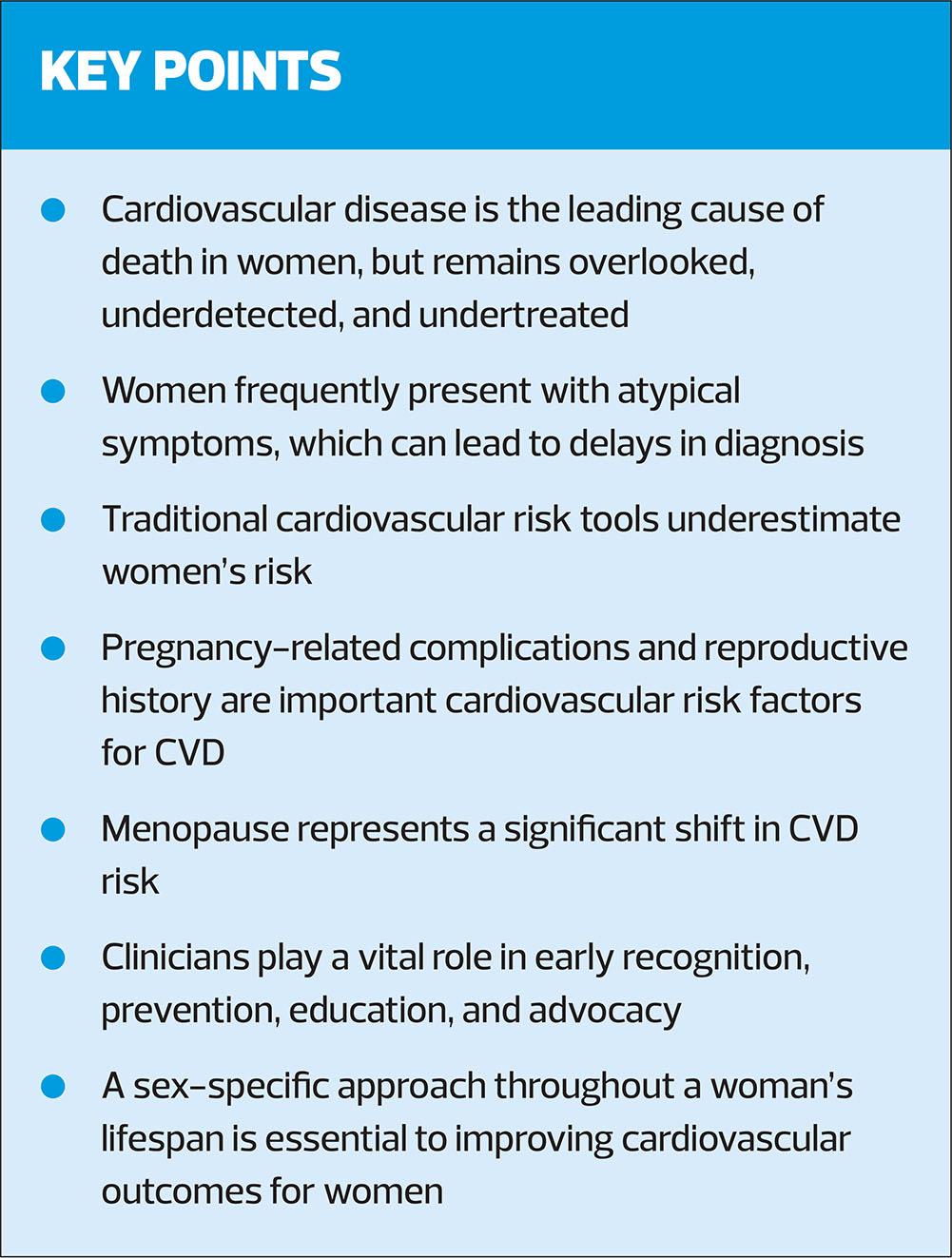

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death in women, yet it is frequently overlooked, underdetected, and undertreated across the lifespan.1–3 Women frequently present with atypical symptoms, experience delays in diagnosis and intervention, and are less likely to receive GDMT, contributing to poorer outcomes compared with men.1,3 Traditional cardiovascular risk tools underestimate women’s risk and the influence of hormonal changes on CVD risk is often overlooked.8,11,12 Accurate coding and proactive management of pregnancy- and menopause-related risk factors, alongside traditional risk factor control, are essential for effective primary and secondary prevention.15 Sex-specific anatomical, physiological, and pathological differences also influence disease presentation and treatment response across conditions such as CAD, heart failure, valvular disease, arrhythmias, and Takotsubo, highlighting the need for clinician awareness and tailored approaches.1,11,16,17 Clinicians play a pivotal role in early recognition, prevention, patient education, and advocacy to bridge the persistent disparity in cardiovascular outcomes between women and men. By integrating sex-specific risk assessment, optimising management strategies, and applying GDMT, healthcare providers can improve morbidity and mortality for women with cardiovascular disease.1,10

References

- Tayal U, Pompei G, Wilkinson I, et al. Advancing the access to cardiovascular diagnosis and treatment among women with cardiovascular disease: a joint British Cardiovascular Societies’ consensus document. Heart 2024;110(22):e3–15.

- Appelman Y, Gulati M, Roeters van Lennep JE, et al. Cardiovascular disease in women: traditional and sex-specific risk factors. Eur Heart J. 2025;ehaf1001.

- Gauci S, Cartledge S, Redfern J, et al. Biology, bias, or both? The contribution of sex and gender to the disparity in cardiovascular outcomes between women and men. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2022;24(9):701–8.

- El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, et al. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: implications for timing of early prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020;142(25):e506–32.

- Morales-Suarez-Varela M, Guillen-Grima F. Cardiovascular Risk During Pregnancy: Scoping Review on the Clinical Implications and Long-Term Consequences. J Clin Med 2025 Oct 23;14(21):7516.

- Wu P, Haththotuwa R, Kwok CS, et al. Preeclampsia and future cardiovascular health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(2):e003497.

- Li Y, Kurinczuk JJ, Alderdice F, et al. Pre-pregnancy care in general practice in England: cross-sectional observational study using administrative routine health data. BMC Public Health. 2025 Mar 22;25(1):1101.

- Haws J, Nuttall M. QRISK4: What’s on the horizon in CVD risk assessment. Practice Nurse 2025;55(2):22-25.

- Lee SM, Shivakumar M, Park JW, et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective UK Biobank study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022;21(1):221.

- Appelman Y, Gulati M, Roeters van Lennep JE, et al. Cardiovascular disease in women: traditional and sex-specific risk factors. Eur Heart J. 2025;ehaf1001.

- Luca F, Abrignani MG, Parrini I, et al. Update on management of cardiovascular diseases in women. J Clin Med 2022;11(5):1176.

- Thurston RC, Aslanidou Vlachos HE, Derby CA, et al. Menopausal vasomotor symptoms and risk of incident cardiovascular disease events in SWAN. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(3):e017416.

- LaVasseur C, Neukam S, Kartika T, et al. Hormonal therapies and venous thrombosis: Considerations for prevention and management. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2022;6(6):e12763.

- Foschi M, Groccia G, Rusce ML, et al. Estradiol and Micronized Progesterone: A Narrative Review About Their Use as Hormone Replacement Therapy. J Clin Med 2025 Oct 16;14(20):7328.

- NICE NG238. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification; 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng238

- Lainščak M, Milinković I, Polovina M, et al. Sex-and age-related differences in the management and outcomes of chronic heart failure: an analysis of patients from the ESC HFA EORP Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22(1):92–102.

- Abuelazm M, Saleh O, Hassan AR, et al. Sex difference in clinical and management outcomes in patients with takotsubo syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Problems Cardiol 2023 Apr 1;48(4):101545.

Related articles

View all Articles