Cardiometabolic disease, inflammation and ageing: what’s the link?

Beverley Bostock RN MSc MA QN President-Elect Primary Care Cardiovascular Society ANP Long-Term Conditions, Mann Cottage Surgery, Moreton in the Marsh

Practice Nurse 2026;56(1):26-30

Ageing is associated with chronic low-level inflammation and reduced capacity for tissue repair which are now known to be implicated in the development of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

In recent years there has been an increasing level of interest in the impact of inflammation on the pathophysiology of cardiorenal metabolic conditions such as diabetes, chronic kidney disease and heart disease, neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia and Parkinson’s disease, and other long-term conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.People living with these conditions often have increased inflammatory markers including raised levels of ferritin, C-reactive protein and serum uric acid.Ageing is also associated with chronic low-level inflammation, which, coupled with a reduced capacity for tissue repair, increases vulnerability to disease. The term for this relationship between ageing and inflammation, is 'inflammaging'. Healthcare professionals need to be aware of the link between inflammation, long-term conditions and ageing in order to make appropriate recommendations to reduce the effect on the onset and progression of chronic and age-related diseases. This article explores the biological mechanisms underpinning chronic inflammation, examines its clinical consequences, particularly on older people, and explores the potential interventions which could implemented to reduce future risk.

IMPACT OF THE INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE ON CARDIORENAL METABOLIC DISEASE

Inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have been recognised as risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) to the extent that they are included in the QRISK 3 cardiovascular risk assessment tool.Other inflammatory conditions which are known to be associated with an increased risk of CVD include psoriasis and HIV.1The inflammatory and immune response involves pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukins, and monocytes and macrophages, all of which can impact on CVD risk, especially in older people, where the term ‘inflammaging’ has been used.

In obesity, the excess adipose tissue is now recognised to be an active endocrine organ, which, among other actions, releases cytokines that drive insulin resistance, raise blood glucose levels, negatively impact on beta-cell mass and function and potentially lead to type 2 diabetes (T2D).2As well as increasing the risk of T2D, these chronic inflammatory changes increase the risk of the complications of diabetes, including retinopathy, nephropathy and CVD.Furthermore, there is an association between these conditions and others such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, polycystic ovarian syndrome and gout.2,3

Another cause of inflammation is hypoxia, which has been shown to be more common in people living with obesity.4This is also a feature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a condition which is associated with an increased risk of CVD, especially following an exacerbation.5Many people with COPD live with multimorbidity, having other long-term conditions which might further increase their risk of systemic inflammation and inflammaging.

ESC GUIDELINES

Cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) mention the link between inflammatory disease and CVD risk, and includes other conditions as risk factors because of the underlying inflammatory processes.6These include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where CVD risk is increased by 20%, and ankylosing spondylitis and chronic kidney disease (CKD) because of the link with uraemia and inflammation.These guidelines also highlight environmental pollution including that from traffic, power plants, and industrial and residential heating using oil, coal, and wood, which are drivers of systemic inflammation, resulting in a loss of 2.9 years lifespan on average.6

WHAT IS INFLAMMAGING?

The term 'inflammaging' describes the persistent, chronic and sustained low-level systemic inflammation observed in older people.3 It is different from acute inflammation, which is a protective response to injury or infection.The concept of inflammaging developed as a result of observations that older people often exhibited elevated levels of inflammatory markers, even in the absence of injury or infection, and that this background inflammation was actively contributing to the pathogenesis of many age-related diseases.3 As cells age, a process known as cell senescence, and cell renewal slows down, inflammatory mediators are released, which have both local and systemic effects.In animals, removing these ageing cells has resulted in reduced levels of inflammation and improvements in tissue function.Other changes observed include immunosenescence, where the actions of the ageing immune system are impaired.Thus, the immune system becomes weaker and is less able to function effectively (including a reduced response to vaccines), leaving the older person increasingly vulnerable to chronic inflammatory diseases and acute infections.Mitochondrial dysfunction, which is common in the tissues of older people, further fuels the inflammatory cascade while epigenetic changes, affecting the DNA, also play their part.

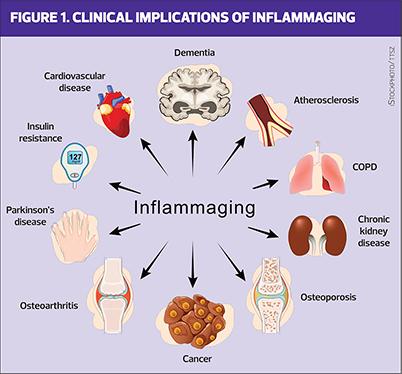

CLINICAL CONSEQUENCES OF INFLAMMAGING

The clinical implications of inflammaging are far-reaching because persistent inflammation is a driving force behind a spectrum of age-related diseases. As described above, cardiometabolic conditions, including T2D and obesity, are closely associated with chronic inflammation.Indeed, this was the reason why people living with pre-existing inflammatory diseases and obesity had worse outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic.7In CVD, chronic inflammation contributes to endothelial dysfunction, atherogenesis, and plaque instability, increasing the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke.3 Furthermore, inflammaging has a significant impact on both morbidity and mortality in older adults: elevated inflammatory markers are predictive of frailty, disability, and reduced physical function.3

BLOOD TESTS FOR INFLAMMATION

Blood tests are often carried out in general practice if an inflammatory disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, is suspected.However, the results can be unreliable and non-specific, often leaving the clinician with as many questions as answers.Tests such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), plasma viscosity and C-reactive protein (CRP) may be abnormal, indicating the possibility of inflammation or infection but they will not identify the site of the problem or the source of the raised marker. The high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) test is, as its name suggests, a more sensitive test than the standard CRP test and can identify smaller increases in CRP which have been linked to an increased risk of developing CVD.However, this test is rarely performed in standard practice.

Ferritin is released from cells in the presence of inflammation, so a raised ferritin level is another inflammatory marker,8 while a raised serum uric acid (SUA) level is also associated with inflammation and an increased risk of CVD.9People with raised SUA levels and symptoms may be diagnosed with gout and this condition has also been associated with a higher risk of CVD, atrial fibrillation and diabetes.10,11

Overall, blood tests may help to identify people with raised inflammatory markers who are suspected of having other inflammatory conditions such as RA or SLE, but their poor sensitivity and specificity mean that they are not used routinely in assessing cardiorenal metabolic risk and the ESC guidelines specifically discourage the use of blood tests such as CRP for CVD.

PHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS

The link between inflammation, ageing and multiple long-term conditions is often overlooked in clinical practice.The question is, then, what can be done to address these inflammatory changes, especially in older people.Is it the case that healthcare professionals should be recommending interventions to reduce inflammation and the risk of long-term conditions, morbidity and mortality?Can we do more to impact on inflammaging or could this be seen as another attempt to ‘medicalise’ older age, to legitimise gerascophobia, which is the fear of the normal physical and mental decline associated with ageing?Are there any evidence-based interventions?

The ESC guidelines mention inflammation several times but also point out the general lack of evidence for interventions.6 They do recommend that standard risk reduction strategies should be implemented, such as lipid lowering therapies.Statins have been shown to exert an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting key inflammatory pathways, reducing inflammatory cytokines, decreasing C-reactive protein (CRP), and improving endothelial function.12 However, statins are primarily prescribed on the basis of their effect on lowering LDL-cholesterol rather than for their anti-inflammatory effect. Healthcare professionals might want to consider including this information when explaining the possible benefits of statins to patients.In T2D, CKD and CVD guidance, the usual advice is to offer lipid lowering therapies to people with a raised CVD risk score along with blood pressure treatment, smoking cessation and other lifestyle interventions as appropriate.

In high-risk individuals with CVD, colchicine can be used for its anti-inflammatory effect.13 This drug has been used for years in people with gout, especially if they cannot take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).A daily dose of 0.5mg is recommended in the ESC guidelines.6

Several other pharmacological agents with potential anti-inflammatory and anti-inflammaging effects exist, but again, these additional benefits may be overlooked by many clinicians. Metformin has demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties and may have the potential to delay age-related morbidity, although there are concerns around the validity of this latter claim.14,15 The GLP-1 RA class of drugs (glutides) has been shown to have important anti-inflammatory effects in addition to their glycaemic, weight and cardiovascular benefits.16 Sodium glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors (flozins) have been shown to reduce CVD and heart failure risk as well as being beneficial in T2D, but they have also been shown to lower circulating levels of SUA and may have a role to play in gout, which is associated with an increased risk of cardiometabolic disease.17However, none of the existing drugs in this class are licensed to be used in this way.Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors (gliptins) have also been shown to modulate the inflammatory response.18 As previously mentioned, statins exert anti-inflammatory effects and may confer additional benefits in older patients at risk of cardiovascular disease.Other lipid-lowering drugs, including bempedoic acid and ezetimibe, have shown anti-inflammatory effects.19

More recently, biologic agents that specifically target pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., anti-IL-6 or anti-TNF therapies) have shown efficacy in some chronic inflammatory conditions. However, their application in the context of inflammaging requires further investigation with regard to safety and efficacy.Canakinumab is a monoclonal antibody that acts as an immunosuppressant, and the results of the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study suggested that addressing systemic inflammation in humans could offer advantages in cardiometabolic disease.20 However, side effects included fatal infections, and the cost of the drug made it unviable.

There is an emerging interest in the use of senolytics – drugs that selectively eliminate senescent or so-called ‘Zombie’ cells – and these have shown promising preclinical results, although clinical trials are ongoing to determine their efficacy and safety in humans.21

In people with pre-existing inflammatory conditions such as RA, SLE, IBD and others, the advice is to manage that condition and its associated inflammation in the usual way, but to recognise that they are likely to be at increased risk of cardiometabolic conditions and to address this appropriately.6

In the meantime, the precise mechanisms connecting chronic inflammation and cardiometabolic disease and the best way to address these remain a subject of active research.

LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS

What is known, however, is that lifestyle interventions offer a non-pharmacological approach to reducing inflammation and inflammaging. Although exercise might more commonly be associated with muscle inflammation, there is also evidence that it has an anti-inflammatory effect which might benefit cardiometabolic wellbeing.Regular physical activity has been shown to lower systemic inflammation, especially inflammaging, improve immune function, and delay the onset of age-related diseases.22

Diets rich in anti-inflammatory nutrients – such as the Mediterranean diet, which focuses on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats – are associated with lower levels of inflammation. The British Heart Foundation has information on how to include foods with possible anti-inflammatory properties in the diet and more information on the subject can be found here: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/heart-matters-magazine/nutrition/anti-inflammatory-diet (https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/heart-matters-magazine/nutrition/anti-inflammatory-diet).However, as the BHF article points out, the claim that foods are ‘anti-inflammatory’ is not recognised in the UK, and companies should not use this description on their products.Gut microbiome imbalance has also been linked to an increased risk of cardiorenal metabolic disease.23

Smoking increases the level of circulating inflammatory markers and quitting has been shown to reduce these markers.24 Hazardous drinking has been associated with an increased inflammatory response, so moderating alcohol intake further contributes to inflammation reduction.25

These strategies are pragmatic, and carry wide-reaching health benefits, so can readily be incorporated into standard clinical advice for both younger and older adults.Indeed, these recommendations will be familiar to many people with long-term conditions such as T2D, CVD and respiratory disease but the additional anti-inflammatory message should also be stressed.

CONCLUSION

The link between inflammation and cardiometabolic disease is becoming clear, while the concept of inflammaging represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of age-related disease. The clinical consequences of inflammation extend across a range of long-term conditions, underscoring the importance of recognising this link and intervening early with lifestyle changes and medication.Inflammaging is a central driver of morbidity and mortality in older adults.However, despite significant progress, numerous questions remain regarding the mechanisms and management of inflammation and inflammaging. Further research is needed to define and address the precise cellular and molecular pathways that drive chronic inflammation, especially in ageing, and the importance of identifying reliable biomarkers for detecting this and developing targeted interventions with minimal side effects is clear. Nonetheless, ageing is shaped by genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors, not simply biological change, and this will necessitate a personalised approach to prevention and treatment.In the future, it may be considered standard practice to integrate an assessment of inflammatory status into routine clinical practice, allowing us to implement novel pharmacological interventions as evidence emerges.For now, the key is to promote evidence-based lifestyle modifications along with established medications, such as statins, which are associated with reducing risk.Multidisciplinary collaboration between primary and secondary care, involving GPs, nurses, pharmacists, cardiologists, diabetologists, nephrologists, geriatricians and immunologists will enhance the development and implementation of effective strategies to combat the burden of inflammatory changes and inflammaging.

REFERENCES

- Aksentijevich M, Lateef SS, Anzenberg P, et al. Chronic inflammation, cardiometabolic diseases and effects of treatment: Psoriasis as a human model. Trends Cardiovascul Med 2020;30(8):472–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2019.11.001

- Rohm TV, Meier DT, Olefsky JM, Donath MY. Inflammation in obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Immunity 2022;55(1):31–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2021.12.013

- Singh A, Schurman SH, Bektas A, et al. Aging and Inflammation. Perspect Med 2024;14(6): a041197. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a041197

- Smith GI, Mittendorfer B, Klein S. (2019). Metabolically healthy obesity: facts and fantasies. J Clin Investigat 2019;129(10):3978–3989. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI129186

- Polman R, Hurst JR, Uysal OF, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk in COPD: a state of the art review. Exp Rev Cardiovascul Ther 2024;22(4-5):177–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779072.2024.2333786

- Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al, for the ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2021;42(34):3227–3337. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484

- Liang W, Liang H, Ou L, et al,for the China Medical Treatment Expert Group for COVID-19. Development and Validation of a Clinical Risk Score to Predict the Occurrence of Critical Illness in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. JAMA Int Med 2020;180(8):1081–1089. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2033

- Kell DB, Pretorius E. Serum ferritin is an important inflammatory disease marker, as it is mainly a leakage product from damaged cells. Metallomics 2014;6(4), 748–773. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3mt00347g

- Piani F, Borghi C. Elevated uric acid as a risk factor. e-Journal of Cardiology Practice ol. 2021:20(11). https://www.escardio.org/Journals/E-Journal-of-Cardiology-Practice/Volume-20/elevated-uric-acid-as-a-risk-factor

- Singh JA, Narula J. (2025). Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in gout: is gout an independent risk factor?. Exp Opin Pharmacother 2025;26(17), 1757–1762. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2025.2597993

- Bailey CJ. (2024). Diabetes and gout: another role for SGLT2 inhibitors?. Therap Adv Endocrinol Metab 2024;15, 20420188241269178. https://doi.org/10.1177/20420188241269178

- Diamantis E, Kyriakos G, Quiles-Sanchez LV, et al. The Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Statins on Coronary Artery Disease: An Updated Review of the Literature. Curr Cardiol Rev 2017;13(3), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573403X13666170426104611

- Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, et al, for the LoDoCo2 Trial Investigators Colchicine in Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease. New Engl J Med 2020;383(19), 1838–1847. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2021372

- Lin H, Ao H, Guo G, Liu M. The Role and Mechanism of Metformin in Inflammatory Diseases. J Inflamm Res 2023;16, 5545–5564. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S436147

- Keys MT, Hallas J, Miller RA, et al. Emerging uncertainty on the anti-aging potential of metformin. Ageing Res Rev 2025;111:102817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2025.102817

- Mehdi SF, Pusapati S, Anwar MS, et al. (2023). Glucagon-like peptide-1: a multi-faceted anti-inflammatory agent. Front Immunol 2023;14:1148209. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1148209

- Ferguson LD, Molenberghs G, Verbeke G, et al (2024) Gout and incidence of 12 cardiovascular diseases: a case–control study including 152 663 individuals with gout and 709 981 matched controls. Lancet Rheumatol 2024;6(3):e156 – e167

- Hellenthal KEM, Kintrup S, Wirth T, et al. (2025). DPP4 inhibition curbs systemic inflammation. Crit Care 2025;29(1), 359. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-025-05599-x

- Xie S, Galimberti F, Olmastroni E, Luscher TF, et al, and META-LIPID Group (2024). Effect of lipid-lowering therapies on C-reactive protein levels: a comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cardiovasc Res 2024;120(4), 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvae034

- Everett BM, Cornel JH, Lainscak M, et al. Anti-Inflammatory Therapy With Canakinumab for the Prevention of Hospitalization for Heart Failure. Circulation 2019;139(10), 1289–1299. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038010

- de Magalhães JP. Senolytics under scrutiny in the quest to slow aging. Nat Biotechnol 2025;43:1413–1415

- Sallam N, Laher I. (2016). Exercise Modulates Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Aging and Cardiovascular Diseases. Oxid Medicine Cell Longev 2016, 7239639. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7239639

- Tan J, Chen M, Wang Y, et al. Emerging trends and focus for the link between the gastrointestinal microbiome and kidney disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022;12, 946138. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.946138

- Zhao M, Chu J, Feng S, et al. (2023). Immunological mechanisms of inflammatory diseases caused by gut microbiota dysbiosis: A review. Biomed Pharmacother 2023;164, 114985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114985

- Derella CC, Tingen MS, Blanks A, et al. Smoking cessation reduces systemic inflammation and circulating endothelin-1. Scientif Rep 2021;11(1), 24122. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03476-5

- Tharmalingam J, Gangadaran P, Rajendran RL, Ahn BC. Impact of Alcohol on Inflammation, Immunity, Infections, and Extracellular Vesicles in Pathogenesis. Cureus 2024;16(3), e56923. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.56923

Related articles

View all Articles