A clinical priority: cardiovascular disease prevention

Judith Magowan

Judith Magowan

RN, MSC Dip

Long term condition lead, non-medical prescriber, Okehampton, Devon

Nurse educator, Devon and Cornwall Training Hubs

Practice Nurse 2021;51(2):16-20

The coronavirus pandemic has necessitated new ways of tackling CVD prevention, which remains a clinical priority and has the potential to prevent more than 150,000 heart attacks, strokes and cases of dementia over the next 10 years

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) refers to a group of conditions that affect the heart and blood vessels. It includes heart disease, stroke and transient ischemic attacks, and dementia. CVD is the leading cause of death and disability, despite major improvements in both the detection and management over recent years, and remains a significant cause of health inequality. CVD is estimated to affect about 7 million people and is responsible for a quarter of all deaths and the main cause of premature death in the UK.1 The NHS Long Term Plan (LTP) for Health describes tackling CVD as a clinical priority and as the single clinical area with the greatest potential for saving lives over the next ten years.1 The ambition for CVD is to prevent over 150,000 heart attacks, strokes, and dementia cases over the next 10 years through prevention, early detection and treatment of CVD.1

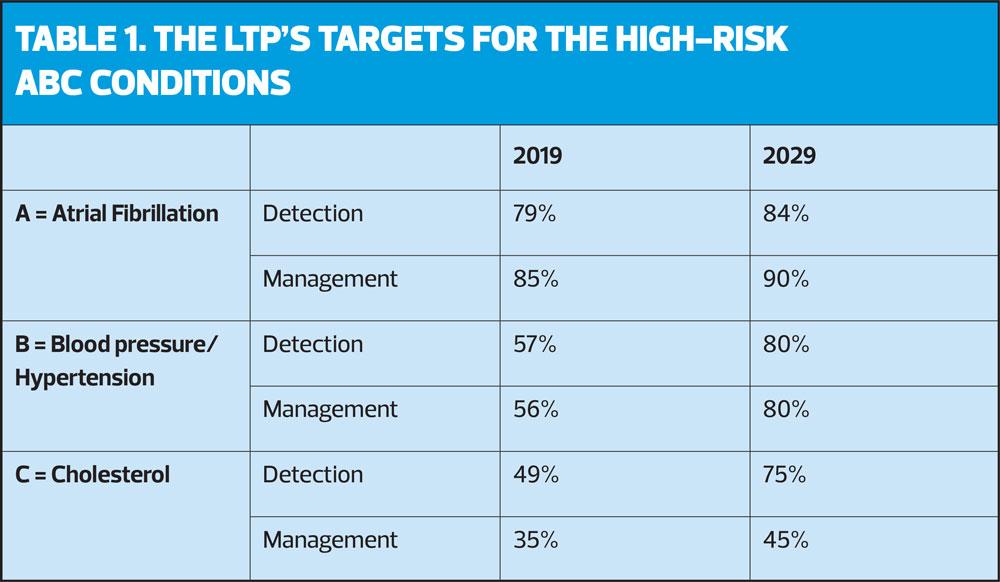

CVD is largely preventable, and the biggest gains can be achieved through primary prevention initiatives, which target individuals without existing disease and promote healthy lifestyle choices and which identify risk factors and high-risk conditions. The LTP strategy for prevention focuses on identifying and treating the three ‘ABC’ high-risk conditions – Atrial Fibrillation (AF), Blood pressure and Cholesterol (Table 1).

Achieving the LTP’s ambitious CVD targets presented an already stretched primary care with a huge challenge but the major disruption to services caused by COVID-19 has threatened to derail progress and even reverse the significant inroads already made towards improvement in CVD prevention, detection, and management.

This article will focus on how health care professionals (HCPs) working in primary care can continue to deliver vital CVD prevention work during in the pandemic through embracing new ways of working which may not only address some of the current barriers experienced due to COVID-19 but could also serve to equip HCPs with the skills and tools to achieve the ambitious targets set out in LTP in the future. The recommendations of the recently published CVD prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidance for primary care teams will be discussed.2

Objectives

This article aims to:

- Discuss the impact of the COVID-19 on CVD prevention in primary care.

- Identify the challenges associated with detection and management of the high-risk A, B and C conditions.

- Explore an enhanced approach to CVD prevention delivery which provides holistic patient-centred care, fully utilises the skills of healthcare professionals (HCPs) and embraces new technology.

THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON CVD

The coronavirus pandemic has impacted on CVD in several negative ways. First, people living with CVD and CVD risk factors are thought to be more susceptible to COVID-19 and at increased risk of poor outcomes.3 While fighting the pandemic is a clinical priority, we cannot afford to lose sight of the importance of continuing essential primary prevention work at this time when patients with CVD are more vulnerable. As general practice nurses are only too aware, the COVID response and unprecedented pressures caused by the virus have resulted in disruption to usual care pathways, reductions in the number of face-to-face consultations and suspension or reduced delivery of NHS health checks and long-term condition reviews. Opportunistic screening, monitoring or management of high-risk individuals and those with existing CVD has become much more difficult.

Data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show 2,085 excess deaths at home from CVD in England and Wales during the first peak of the COVID 19 pandemic, with rates in people under 65 almost 13% higher than usual between May and July.4 This increase in CVD mortality is thought to be due to a combination of factors. Re-prioritisation of secondary care resources has led to reduced testing and elective procedures. Reluctance and delays in seeking health care by individuals when unwell during in the pandemic may be due to both fear of exposure to the corona virus and the perception that healthcare services are overwhelmed by COVID-19. There is thought to have been an increase in unhealthy behaviours such as poor diet, excessive alcohol intake, smoking and reduced physical activity during in the pandemic, which could be in part due to an unintended consequence of imposed restrictions on activity and also as a result of the psychosocial stresses of the pandemic.5

IMPROVING DETECTION OF ABC CONDITIONS

A. AF is characterised by a rapid, irregular heartbeat, which can cause blood clots to form which, in turn, can result in a stroke. AF can be easily detected by checking for an irregular pulse and investigating with an electrocardiogram (ECG). There is a five-fold increased risk of stroke associated with AF, but this risk can be reduced by up to 65% through effective use of anticoagulation therapy.6 The ambition of the LTP is to improve detection rates from 79% detection in 2019 to 84% by 2029 and improve effective management from 85% to 90%.

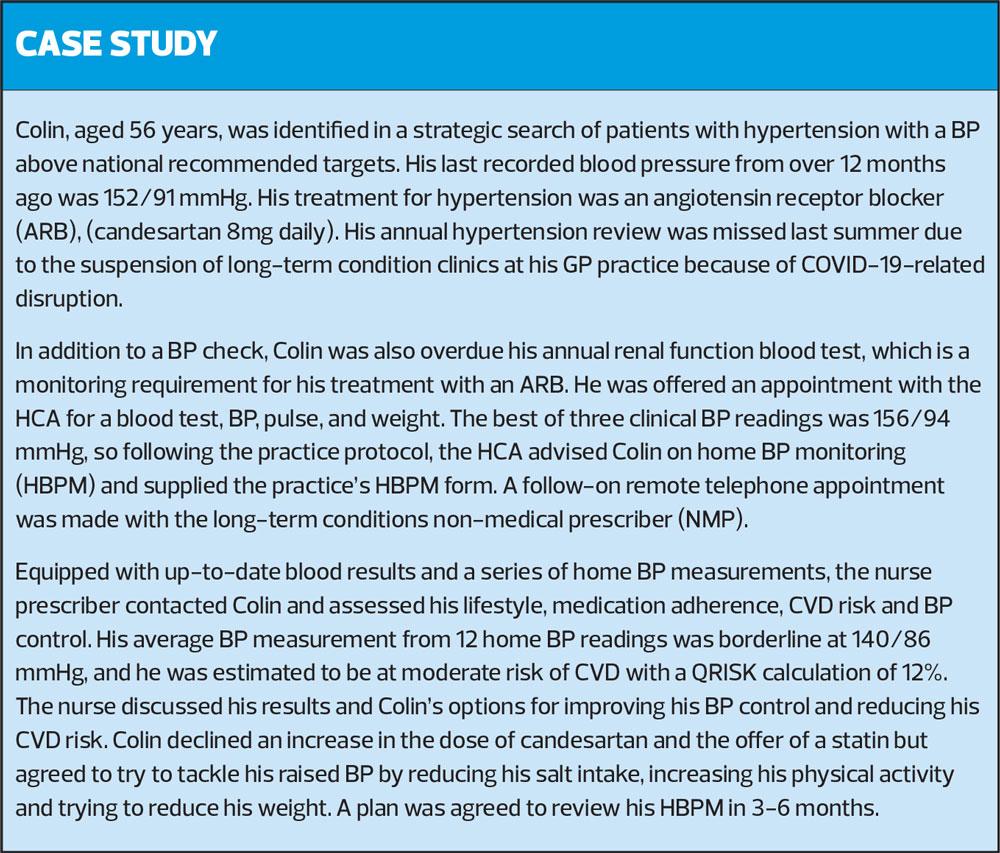

B. Hypertension is the second largest global risk factor for disease and disability (after poor diet) and is responsible for approximately half of all strokes and ischemic heart disease events. Hypertension is estimated to effect one in four adults in the UK but prevalence is increased in areas of deprivation, with hypertension 30% more likely in the most deprived areas of England compared with the least deprived.6 Hypertension detection rates vary considerably between the best and the worst CCGs but average out nationally at just over at an estimated 57% detection. Furthermore, only an estimated 56% of people with hypertension are treated to target levels recommended by national guidelines.7 The LTP goal is to improve detection of underlying hypertension to 80% and to address suboptimal management of hypertension by treating 80% of patients to target.

C. High cholesterol is a well-established CVD risk factor and estimated to be responsible for one in three cases of ischemic heart disease, and to account for 7.1% of deaths in England.6 Testing blood lipids and using an approved CVD risk calculator such as QRISK enables the identification of increased risk. Raised cholesterol can be managed through appropriate lifestyle advice and for those with an estimate CVD risk of >10% over the next 10 years, NICE recommends offering treatment with statins.8 In addition, the LTP aims to improve the diagnosis and treatment of Familial Hypercholesterolaemia (FH) to 25% of cases.

HOLISTIC CARE

CVD risk factors rarely occur in isolation so when reviewing patients consider the presence of other potential high-risk conditions. Palpating and assessing a radial pulse for irregularities when reviewing a patient with hypertension and taking blood to screen for diabetes and lipids are examples of this approach. Holistic assessment of lifestyle and medications adherence is recommended, and the provision of individual patient-centred advice that considers the individual’s ideas, concerns and expectations. Reducing lifestyle risks such as smoking, poor diet, obesity, inactivity, and excessive alcohol consumption is essential to CVD prevention. Signposting patients to credible sources of information such as NHS choices and the British Heart Foundation facilitates patient education and informed decision-making, which are key parts of self-management strategies. Appropriately trained health care assistants (HCAs) can provide support on behaviour change via telephone or video calls in place of traditional face-to-face consultation. Virtual group consultations delivered via an online conferencing platform are another way of promoting positive lifestyle messages and supporting change.

Maximising encounters

As a response to reduced patient contact due to the pandemic, HCPs are encouraged to try and get the most out of each patient encounter, whether face to face or remote, and offer opportunistic screening, monitoring and management of CVD risk factors and condition. If patients are attending for bloods, ECG or dressings then this provides an opportunity to check pulse and blood pressure and to enquire about lifestyles.2 A same day telephone triage appointment for a minor aliment could be a chance to carry out an overdue hypertension review remotely and the patient could be asked to supply some home blood pressure monitoring results.

To make the most of each encounter, primary care needs to train and support the work force to upskill. Training phlebotomists to check pulses, and building on HCA skills such as performing diabetic foot checks are possible approaches.2 Optimal use of CVD prevention medication can be facilitated through non-medical prescribers initiating, reviewing and up-titrating treatments which provide individuals with the right drug at the optimal dose to minimise CVD risk. Working more closely with the wider primary care workforce, including community nurses and community pharmacists, is recommended to deliver care to patients at home if needed.2

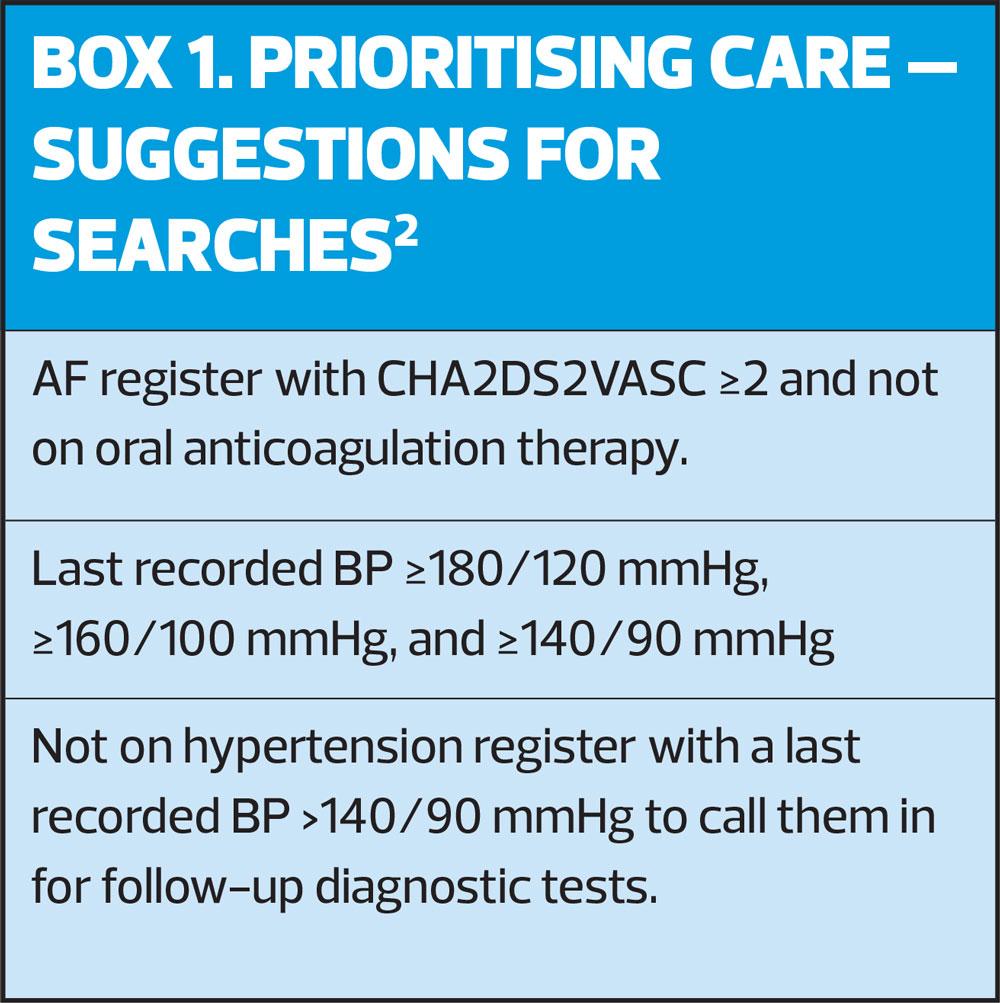

STRATIFYING AND PRIORITISING CARE

While usual provision of care is limited because of the pandemic, it is essential to work in smart ways by stratifying care and prioritising those at most risk, such as the patients with the highest recorded BP. Search strategies for EMIS and SystmOne have been developed to identify those at high risk in primary care and these resources are freely available.2 Simple searches as illustrated in Box 1 can be used to direct reduced services to those who are at most risk. Searching for and contacting patients with poorly controlled blood pressure is an example of this approach. Opportunistic screening of hypertension can continue through searching for patients with no code of hypertension but a recorded clinical BP greater than 140/90 mmHg and arranging relevant investigations to confirm or refute hypertension.

Self-monitoring of hypertension

Out of office blood pressure monitoring using either home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) or ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) has been recommended for some years when diagnosing hypertension.7 Use of HBPM for monitoring patients with hypertension has steadily grown in recent years but has now become a necessity because of the pandemic. Prior to this, only a third of patients with hypertension were thought to own their own blood pressure monitor but this number is likely to have grown significantly over the last year as clinicians have become reliant on HBPM for both diagnosis and monitoring of hypertension, and both practice loan schemes for monitors and ABPM have been suspended as an infection control measure. The British and Irish Hypertension Society recommends a list of validated BP monitors which can be purchased for as little as £20.9 Ensuring that patients use the right size cuff and providing education on correct technique is important to acquiring accurate results. Unfortunately, BP monitors cannot be prescribed but various schemes to provide patients who would most benefit from a monitor, but may not be able to afford one, are beginning to be rolled out such as the British Heart Foundation 500 monitor scheme. The recent ACCU-RATE study reported that clinicians can be confident of the accuracy of patient’s home BP readings if a validated monitor less than 4 years old is used.10 Further evidence supports the efficacy of self-monitoring and self-reporting of HBPM at achieving long-term management of blood pressure to target in hypertension.11 Patients can be empowered to take control of their hypertension through education about effective management strategies such as healthy behaviours and medication adherence, alongside information about the desired average BP targets. A HBPM average of less than135/85 mmHg in the under-80s and less than 145/85 mmHg in the over-80s indicates optimal control.7

DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY

NHSX was launched in 2019 as an integral part of the LTP to unleash the great potential of digital technology to transform the future NHS. This process of digital transformation has greatly accelerated as the delivery of remote care necessitated by the pandemic has seen technology such as online consultations, video and texting services rapidly become the mainstay of care delivery for primary care.

The national primary care audit, CVDPREVENT, was also established to extract GP data covering diagnosis and management of CVD high-risk conditions with the purpose of informing and shaping quality improvement by individual Primary Care Networks (PCNs) by highlighting gaps, identifying inequalities and assessing interventions.

Several digital tools have become available to promote and support patients in self-management of long-term conditions. Omron Connect and Florence are examples of the digital platforms that can be used to promote self-management of hypertension, as well as providing a means of transmitting readings to the clinician remotely.

Digital devices that use smart phone Apps such as Kardia Mobile, Impulse and Zenicor-ECG can be used to detect atrial fibrillation remotely by patients or by a community nurse visiting a patient at home.2

CONCLUSION

CVD is a major risk to the health of individuals and communities and carries huge costs for the NHS and society as whole. It is therefore a clinical priority and the number one area for potential gains in reducing premature deaths. The ambitious targets set by the LTP for improved detection and management of the high risk A,B,C conditions: atrial fibrillation, blood pressure/hypertension and cholesterol will only be achieved if primary care not only continues to provide vital CVD prevention work despite the pandemic but also embraces innovative ways of working. The restraints and pressures of COVID-19 on delivery of care has seen primary care embracing new technology and targeting and prioritising care initiatives. Training and equipping the wider primary care workforce, alongside educating and supporting patients to self-manage are key strategies to ensure CVD prevention continues through out the disruption of the pandemic and towards the future and the ten-year CVD ambitions of LTP.

REFERENCES

1. NHS. The NHS long term plan. 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/online-version/chapter-3-further-progress-on-care-quality-and-outcomes/better-care-for-major-health-conditions/cardiovascular-disease/

2. Oxford Academic Health Science Network (Oxford AHSN) and the Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) programme https://www.gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/new-guidance-helps-primary-care-teams-deliver-best-cvd-services-during-the-pandemic/

3. European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidance; June 2020 https://www.escardio.org/Education/COVID-19-and-Cardiology/ESC-COVID-19-Guidance

4. British Heart Foundation. Thousands of excess deaths from cardiovascular disease during the coronavirus pandemic; September 2020 https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/news-from-the-bhf/news-archive/2020/september/thousands-of-excess-deaths-from-cardiovascular-disease-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic

5. World Heart Federation (WHF). The link between COVID-19 and CVD. https://www.world-heart-federation.org/covid-19-and-cvd/

6. Public Health England. Health Matters – Preventing Cardiovascular Disease; April 2018 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-preventing-cardiovascular-disease/health-matters-preventing-cardiovascular-disease#scale-of-the-problem

7. NICE [NG136] Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management NICE guideline; August 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136

8. NICE CKS. Lipid modification; October 2020

https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/lipid-modification-cvd-prevention/

9. Which? How to buy the best blood pressure monitor; February 2021. https://www.which.co.uk/reviews/blood-pressure-monitors/article/how-to-buy-the-best-blood-pressure-monitor-aO1yE0Z0vwVs

10. Hodgkinson A, et al. Accuracy of blood-pressure monitors owned by patients with hypertension (ACCU-RATE study): a cross-sectional, observational study in central England. Br J Gen Pract 1 June 2020;70(697):e548=e554

11. McManus R, et al. Efficacy of self-monitored blood pressure, with or without telemonitoring, for titration of antihypertensive medication (TASMINH4): an unmasked randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018;391:949-59

Related articles

View all Articles