When asthma is poorly controlled: treating asthma according to the latest BTS/SIGN guideline

Beverley Bostock-Cox

Beverley Bostock-Cox

RGN MSc QN

Nurse Practitioner, Mann Cottage Surgery, Moreton in Marsh

Education Lead, Education for Health, Warwick

The majority of people with asthma in the UK are usually managed in primary care following the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN) asthma guidelines.1 However, not all patients’ asthma is well controlled on standard monotherapies of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus short-acting or long-acting bronchodilators.2 Here we examine the role of tiotropium as add-on therapy when treatment needs to be escalated.

This article was initiated and supported by Boehringer Ingelheim, who have reviewed it for accuracy and compliance with the ABPI Code of Practice. A link to Prescribing information is available at the end of this article.

The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) (2014) report demonstrated that people continue to die preventable deaths as a result of acute asthma exacerbations.3 NRAD noted that confidential enquiries have repeatedly identified potentially avoidable factors that preceded most asthma deaths.3 The new (2016) British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN) asthma guideline states that good asthma control means that the patient has normal lung function, no symptoms and no impact on day to day activities is experienced.2 This is usually achieved through appropriate use of daily preventer medication together with reliever medication when required, no more than three times a week. However, too many people are overusing their reliever inhalers while using too little preventer medication making them vulnerable to acute exacerbations.3

The aim of asthma management is complete control of the disease, which is defined as:

- No daytime symptoms

- No night time awakening due to asthma

- No need for rescue medication

- No asthma attacks

- No exacerbations and no limitations on activity including exercise

- Normal lung function (in practical terms FEV1 and/or PEF >80% predicted or best)

- Minimal side effects from medication2

BTS/SIGN 2016: LATEST GUIDANCE

Initial management

‘Mild’ asthma is a concept that needs treating with care as half of the people whose deaths from asthma were reported in NRAD had ‘mild to moderate’ asthma.3

The BTS/SIGN 2016 guideline for the management of asthma in adults recognises that asthma is an inflammatory condition, which will almost always need anti-inflammatory treatment in the form of an ICS. For people with infrequent, short-lived wheeze, occasional use of reliever therapy as required may be the only treatment needed. However, the new recommendation2 is that clinicians should consider the monitored initiation of treatment with low dose ICS (defined as 400mcg budesonide equivalent, total daily dose) for anyone with any of the following features:

- Using inhaled beta2 agonists three or more times a week;

- Symptomatic three or more times a week;

- Waking one night a week;

- An asthma attack in the last two years.2

ASSESSING CONTROL AND CAUSES OF POOR CONTROL

As identified in the BTS/SIGN 2016 guidance, control can be measured either through symptoms or via objective measurements of lung function (FEV1 or peak expiratory flow rate – PEFR) or indeed both symptoms and lung function measurement. Symptom based tools include the Royal College of Physicians’ ‘Three questions’ (RCP3Q),4 or the Asthma Control Test (ACT).5 If poor control is identified, this should not simply be considered to indicate the need to step up treatment as there may be many other reasons for poor control including non-adherence, either intentional or unintentional, through incorrect dosing, poor inhalation technique or a lack of understanding about what asthma is and how it should be treated, and these should be investigated. Another issue which should be considered is whether the patient is suffering from allergic rhinitis as this can lead to a deterioration in asthma control.6 Treating asthma and concomitant nasal symptoms is likely to improve asthma control and reduce the overall cost of treating these conditions.7

NEXT STEPS

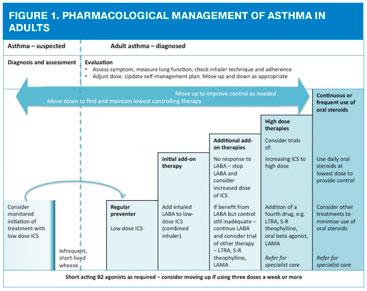

The 2016 guideline-recommended treatment stages – moving up to improve control as needed, and down to find and maintain lowest controlling therapy – can be summed up as follows:

- Low dose ICS (up to 400mcg budesonide equivalent total daily dose)

- Low dose combination (ICS/LABA)

- Medium dose (up to 800mcg budesonide equivalent total daily dose) combination (unless no response to LABA, in which case stop LABA and increase ICS dose alone) or consider LAMA, leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), theophylline

- High dose ICS/LABA (up to 1600mcg budesonide equivalent total daily dose) plus third drug as above with an additional fourth drug if required from the same list (LAMA, LTRA, theophylline)

- Continuous or frequent use of oral steroids, using the lowest dose to provide adequate control, continued high dose ICS, plus other treatments to minimise the use of steroid tablets

So for people whose asthma remains poorly controlled on low dose ICS, the next stage is to consider adding a LABA, normally as a combination inhaler. The majority of treatment of asthma occurs in primary care and most of the patients being treated in general practice will generally be managed with regular ICS, plus or minus initial add-on therapy.1

The dose of ICS should be titrated to the lowest dose at which effective control is maintained. No exact dose of ICS can be deemed the correct dose at which to add another therapy, and many patients will benefit more from add-on therapy than from increasing ICS from as low as 200mcg a day.2

If adequate control is not achieved with an ICS (up to a maximum dose of 800mcg standard beclometasone or budesonide or equivalent) and inhaler technique and adherence are good, additional treatment should be added in.2 As discussed, the first line add-in would usually be a LABA but sometimes an LTRA may be considered.

If good control is still not achieved at this point, additional therapies or increased doses of ICS should be considered (Figure 1). The BTS/SIGN guideline states that all three drugs (an ICS/LABA and an LTRA or LAMA) may be used along with the short acting beta2 agonists to achieve control. Subsequently, the dose of the ICS may be increased up to high dose (e.g. 800mcg budesonide equivalent, twice daily), with the inherent risks that this may incur.8 Other less commonly used drugs may also be considered, such as slow release (S-R) theophylline or oral beta2 agonists. However, these drugs also have side effects and theophylline requires careful titration and monitoring. More information can be found in the summary of product characteristics for each product.

It is important to realise that people who need treatment with high dose ICS/LABA should be referred to a specialist asthma service.2 The NRAD report3 also recommends this approach as it may require the experience of a specialist clinician to identify someone who has other aspects which may be contributing to their inadequate control.

DIFFICULT OR SEVERE ASTHMA

Difficult asthma is a term used in the BTS/SIGN guidance to refer to people with persistent symptoms and/or frequent asthma attacks despite treatment with high dose therapies or continuous or frequent use of oral steroids.2 Causes of difficult asthma include poor adherence to medication regimens, psychological problems, issues such as dysfunctional breathing or reflux or ongoing exposure to allergens or toxins. However, if all of these have been addressed or ruled out, the patient is considered to have severe asthma. Around 5-10% of people with asthma have severe asthma.9 Both difficult and severe asthma will require referral to specialist services in secondary care.

TIOTROPIUM FOR ASTHMA

The BTS/SIGN guideline now includes the recommendation to consider the addition of a long acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) if the patient is benefiting from an increased dose of ICS plus LABA but control is still inadequate.

LAMAs have been used for many years to bronchodilate people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).10 Muscarinic antagonists block acetylcholine receptors in the airways and facilitate bronchodilation in a way which is different from and complementary to beta2 agonists.11 In 2014, tiotropium (Spiriva® Respimat®) was granted a licence at a dose of 2.5mcg, 2 puffs daily as an add-on maintenance bronchodilator treatment in adults who are currently treated with an ICS (at least 800mcg budesonide per day or equivalent) and LABA combination and who have experienced one or more severe exacerbations in the previous year. Studies have shown that this treatment can improve lung function and delay the time to the next exacerbation in this patient group.12–14

In January 2016, a Cochrane review re-examined the addition of tiotropium to combination therapy (ICS/LABA) in asthma.15 This review confirmed that patients taking tiotropium in addition to an ICS/LABA had improvements in lung function, better overall asthma control and fewer exacerbations than those on an ICS/LABA alone, although the evidence for the difference between the two treatment regimens was inconclusive.

Spiriva® Respimat® can be initiated by HCPs in the primary care setting for appropriately assessed asthma patients.HCPs may already be familiar with tiotropium as it is also licensed as a maintenance treatment for COPD.

Nonetheless, it is essential that a full assessment of the reasons for inadequate control is made before starting any patient on additional add-on therapies, and that any issues such as poor adherence or co-morbidities are addressed. If, following a full review, it is deemed appropriate to start a LAMA, the subsequent effect of the treatment should be carefully assessed. Any patient who is already receiving, or who is about to be prescribed high dose ICS should be referred. It should be noted that at this stage there is currently no licence for any other LAMA apart from tiotropium via the Respimat® device in asthma management.

USING THE RESPIMAT® DEVICE

The Respimat® device should be primed and prepared prior to use. Before using for the first time, the cartridge which contains the medication should be loaded into the device and test doses should be released (aimed at the ground) until the mist appears. Once this has been done, the device will still have a full 30 days’ worth of treatment left inside. Once it has been prepared, the device is used by turning, opening the lid and pressing the dose release button – the so-called TOP approach.

T – Turn the clear base in the direction of the arrows until a click is heard

O – Open the mouthpiece and close the mouth around it

P – Press the dose release button and inhale slowly and deeply.

This procedure should be repeated twice in order to get the full dose of medication. The dose indicator on the device turns red when there is one week of medication left and when the last dose has been taken, the device locks out.

Common side effects include a dry mouth. The summary of product characteristics also states that tiotropium should be used with caution in people with narrow angle glaucoma or prostatic hypertrophy and/or bladder neck obstruction. It should also be avoided in people who have recently had a myocardial infarction (within the past 6 months) or who suffer from an arrhythmia or symptomatic heart failure.16

CONCLUSION

In summary, people with asthma are usually managed in primary care on low to moderate doses of ICS plus/minus LABA. However, if other reasons for poor control have been excluded, some people may require escalation of treatment and others may require referral to specialist asthma services. Traditionally, the next stage of treatment includes the use of an ICS/LABA combination (taking the dose of ICS up to 800-1000mcg budesonide equivalent) along with an LTRA, slow release theophylline or oral beta2 agonist.

New evidence suggests that using a LAMA may offer improved control without increasing the dose of ICS, thus limiting the potential risks of high dose ICS. Tiotropium delivered via the Respimat® device is the most recent addition to add on therapies for patients who are no longer controlled without increasing the dose of ICS, is in line with evidence-based practice and is supported by the latest BTS/SIGN guideline as a potential third line option as add on therapy.

SELF-ASSESSMENT

A CPD module to assess your knowledge of the Management of poorly controlled asthma according to the BTS/SIGN guideline is available in the Practice Nurse Curriculum. Click here to access the module, which can be used towards your revalidation portfolio.

PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

Click here for abbreviated prescribing information

REFERENCES

1. Small I. The majority of asthma cases can be managed in primary care. Guidelines in Practice, July 2012. Available at: https://www.guidelinesinpractice.co.uk/jul_12_small_asthma_jul12

2. British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British guideline on the management of asthma, 2016 http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/SIGN153.pdf

3. Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills: The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD), 2014 https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills

4. Pinnock H, Burton C, Campbell S, et al. Clinical implications of the Royal College of Physicians three questions in routine asthma care: a real-life validation study. Prim Care Respir J 2012; 21: 288-94. http://www.nature.com/articles/pcrj201252

5. Asthma UK. Asthma Control Test. http://www.asthmaprojectpack.co.uk/asthma-control-test-act/adult-act

6. Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P and Khaltaev N (2001) Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2001;108(5): S147-S334.

7. Price D, Zhang Q, Kocevar VS, et al. Effect of a concomitant diagnosis of allergic rhinitis on asthma-related health care use by adults. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2005;35(3):282-287

8. d’Ancona G. Inhaled corticosteroids: managing side effects, Pharmaceutical Journal 2015;294(7851) http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/learning/learning-article/inhaled-corticosteroids-managing-side-effects/20067896.article

9. Robinson, D.S., Campbell, D.A., Durham, S.R. et al (2003) Systematic assessment of difficult-to-treat asthma. European Respiratory Journal 2003;22(3):478-483.

10. Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease. COPD guidelines, 2016. www.goldcopd.org

11. Ejiofor S, Turner AM. Pharmacotherapies for COPD. Clinical Medical Insights: Circulatory, Respiratory and Pulmonary Medicine. 2013;7:17-34

12. Anderson DE, Kew KM, Boyter AC. (2015) Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) added to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) versus the same dose of ICS alone for adults with asthma. Cochrane Review, 2015. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011397.pub2/pdf

13. Bateman ED, Kornmann O, Schmidt P, et al. Tiotropium is noninferior to salmeterol in maintaining improved lung function in B16-Arg/Arg patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128(2):315-22.

14. Evans DJW, Kew KM, Anderson DE, et al. Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) added to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) versus higher dose ICS for adults with asthma. Cochrane Review, 2015. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011437.pub2/pdf

15. Kew KM, Dahri K. Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) added to combination long-acting beta2-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids (LABA/ICS) versus LABA/ICS for adults with asthma. Cochrane Review 2016. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011721.pub2/pdf

16. Electronic Medicines Compendium (2016) Spiriva Respimat 2.5mcg inhalation solution https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/20134l

Websites accessed October 2016

Related articles

View all Articles