What should we be doing for our patients with difficult or severe asthma?

Charlotte Renwick

Charlotte Renwick

MSc

Policy Analyst, Asthma UK

Katie Stokes

BA

Policy Officer, Asthma UK

Samantha Walker

PhD

Deputy CEO and Director of Research

and Policy, Asthma UK

Many patients with ‘difficult’ and ‘severe’ asthma are failing to get the specialist care that could prevent frequent hospital admissions, improve quality of life and result in life-changing treatment. Primary care practitioners can take simple steps to identify and refer those patients most likely to benefit

Asthma is often perceived as a single condition, managed effectively with standard preventative medication such as inhaled corticosteroids (ICS). But in an average GP practice, 70 of the 420 patients with asthma might have ‘difficult’ asthma, and 15 could be suffering from ‘severe’ asthma.1,2 Understanding the difference between these two types of asthma can be a challenge.

WHAT IS ‘DIFFICULT’ OR ‘SEVERE’ ASTHMA?

Approximately one million people in the UK (17% of the total asthma population) have ‘difficult’ asthma.3 For this group of people, asthma frequently impacts their everyday lives. They experience uncontrolled symptoms, such as coughing, shortness of breath and wheezing, and a high burden of asthma attacks, often leading to a hospital admission and even death.4 ‘Difficult’ asthma is often the result of poor adherence, other comorbidities and/or wrong diagnosis.4

Of the 1m people with ‘difficult’ asthma, 21% are said to have ‘severe’ asthma. This equates to 3.6% of the total asthma population, approximately 200,000 people in the UK.3 ‘Severe’ asthma is a type of asthma which does not respond to current, readily available treatment, even when adherence to that treatment is good. It can, however, be difficult to differentiate between ‘difficult’ and ‘severe’ asthma.

People with difficult/severe asthma are typically high users of primary care – attending twice as frequently as other patients with asthma,5 and the condition can have a devastating impact. Lives are disrupted by regular A&E visits, hospital admissions and the debilitating side effects of the mainstay of severe asthma treatment, oral corticosteroids (OCS). The toxic side effects of OCS are well known and include mood swings, osteoporosis and diabetes.6

In 2014, the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) report recommended that people with asthma should be referred to a specialist asthma service if they require more than two courses of corticosteroids (oral or injected) within 12 months, or require management using British Thoracic Society (BTS) treatment level 4 or 5 to achieve control (i.e. high dose ICS with a controller).7 Asthma UK’s 2018 report, ‘Slipping through the net: The reality facing patients with difficult and severe asthma’, showed that 89% of primary and secondary care clinicians would only refer after three or more courses of OCS and that there is significant variation across the UK in who is being referred.4 One severe asthma clinician interviewed by Asthma UK explained: ‘The problem is long-term damage done by steroids by the time patients get to us. Also, once they are stable on steroids, they kind of slip through the net. Their hospital admissions reduce, so they’re not flagged up as often.’

The lack of universal guidelines for recognising and treating difficult/severe asthma may be contributing to some of this variation across services and between clinicians.4

Case Study 1

Laura, 29, is on a high dose ICS and is over-reliant on her short acting beta 2 agonist (SABA) reliever inhaler throughout the day. In the last year, she has been prescribed OCS five times and has been hospitalised. She is an ideal candidate for referral to a specialist asthma clinic, but her primary care team (her GP and asthma nurse) has not yet identified her as having difficult/severe asthma.

This article will address what primary care clinicians can do to help improve the lives of people, like Laura, who are so seriously affected by their asthma. With systematic assessment, and referral to specialist asthma clinics there is new hope for these individuals with difficult/severe asthma. They will have access to multidisciplinary teams who are better equipped to assess and address their complex needs and, for those who meet the eligibility criteria, life-changing new biologic drugs.

RULING OUT POOR ADHERENCE AND ASSESSING CONTROL

Poor adherence to treatment, either intentional, unintentional, or because of poor inhaler technique, is a common reason for people to have uncontrolled asthma. However, it is important that people who have uncontrolled asthma despite good adherence to their medication and good inhaler technique are referred for a specialist opinion in secondary or tertiary care. This is highlighted by the NICE Quality Standard on asthma, Quality Statement 3: Monitoring asthma control.8 In order to identify these individuals all healthcare professionals who care for people with asthma should routinely check the relevant markers of poorly controlled asthma and make a subsequent referral if necessary.

Adherence to treatment and over-use of bronchodilators can be assessed by looking at the patient’s computer record for the number of preventer and reliever inhalers they have been prescribed. Most people with asthma would be expected to use approximately 12 preventer inhalers a year. Although this may, of course, vary depending on the medication, the number of doses in the inhaler and the prescribed dose,7 this simple check can be a useful starting point. And identifying poor adherence is important because the NRAD report found that in 38% of the asthma deaths patients had been prescribed less than four preventers in the previous year and in 80% of the deaths less than the 12 that one would expect if patients were adhering to their prescribed preventer medication.7

Some patients may over-rely on their reliever inhaler because they are not using their preventer inhaler correctly. It is essential to check that patients are using the correct inhaler technique (see Asthma UK’s inhaler videos for more on inhaler technique, at https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/inhaler-videos/) and if they are, further investigations into their adherence should be made.

The ‘Asthma Right Care’ movement, an initiative led by the International Primary Care Respiratory Society, has developed a useful tool called the Asthma Slide Rule (https://www.pcrs-uk.org/resource/asthma-slide-rule) to help healthcare professionals easily identify over-reliance on reliever inhalers by asking how much a patient uses their reliever inhaler over varying time periods.9 If patients are using 12 or more reliever inhalers a year (or more than one a month), an urgent review of their medication and adherence is needed and they should be referred to a specialist if this overreliance cannot be addressed immediately. This is critical because as many as 39% of the patients studied in NRAD had been prescribed more than 12 reliever inhalers in the year before they died.7

WHEN TO REFER

Those identified as correctly adhering to their medication, yet still struggling with uncontrolled asthma, are a strong case for referral. An indication for immediate referral, as recommended in the NRAD report and by the NICE Quality Standard for asthma, is the need for more than two courses of OCS within the last 12 months. Patients who have had multiple courses of OCS (or maintenance OCS) in the last 12 months should always be referred to specialist care for immediate attention by a team of respiratory experts able to establish difficult/severe asthma.

BTS also provides guidance on referral criteria and states that patients on BTS treatment level 4 or 5 (high dose ICS with one of the following controllers: leukotriene receptor antagonists [LTRA], SR theophylline, beta agonist tablet, long acting muscarinic antagonist [LAMA] or continuous OCS) should be referred.10 (Box 1)

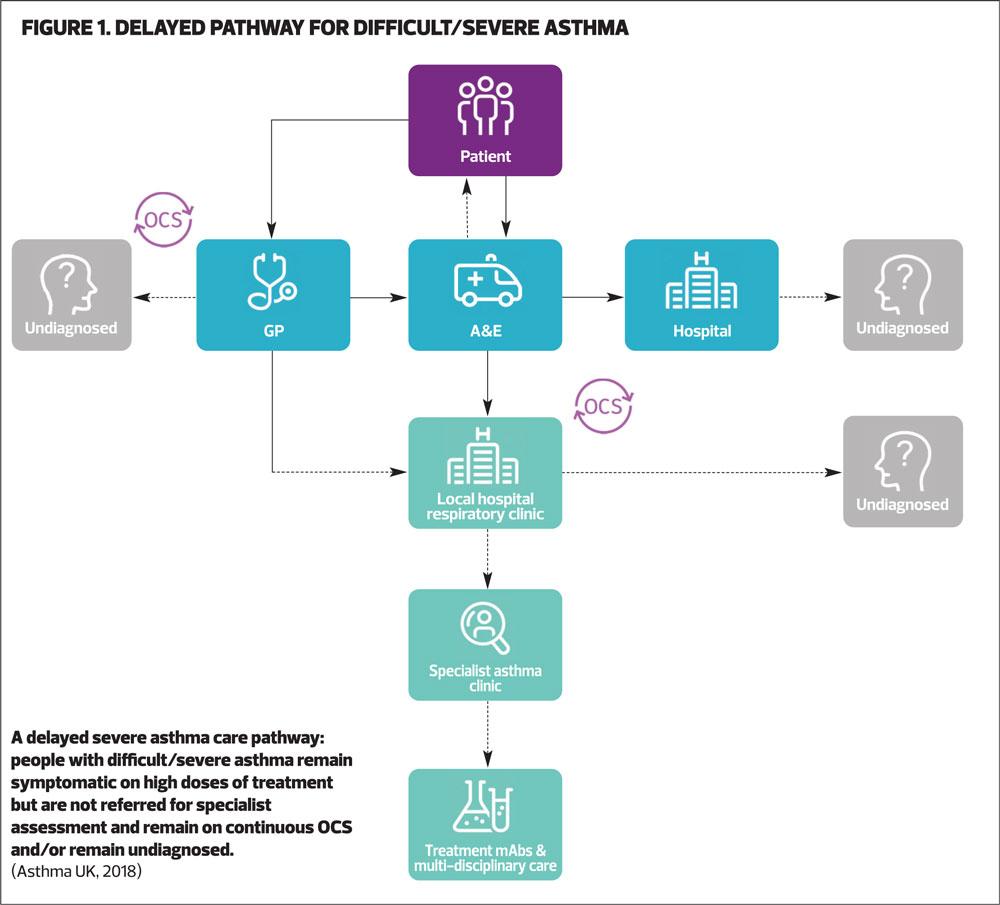

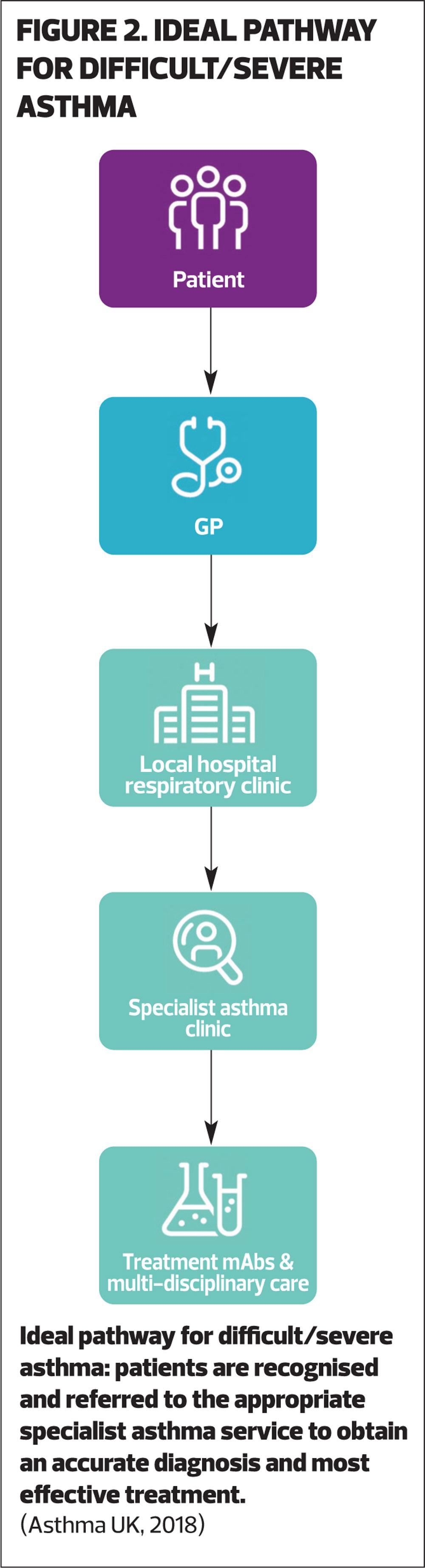

Lack of coordination between primary and secondary care can result in people having frequent trips to A&E, hospital admissions and courses of OCS because their symptoms are not optimally controlled or managed. Figure 1 shows the patient experience if difficult/severe asthma is not identified. However, if patients that may have difficult/severe asthma and need further investigation are identified, referring them to the appropriate specialist asthma services will ensure that these patients get the right diagnosis and treatment. Figure 2 details how this pathway should be much simpler. In this pathway, patients are recognised as having difficult/severe asthma and are then referred to the appropriate specialist asthma services to obtain the right diagnosis and treatment.

SPECIALIST ASTHMA SERVICES

At a specialist asthma service, clinicians have access to a much broader range of diagnostic tools, and are therefore better able to establish if a patient has severe or difficult asthma. As well as specialist blood tests (eosinophil levels), fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) and imaging, they will also have access to physiotherapy, psychology and specialist lung function tests.

FeNO is a test for patients with allergic or eosinophilic asthma and determines how inflamed a patient’s lungs are and how well ICS are suppressing this inflammation. This can help inform a clinician if a patient is on the correct ICS dose. A blood test can also be done to measure a patient’s eosinophil count and immunoglobulin E (IgE) level, which will establish if they have eosinophilic asthma or persistent allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma.

Once severe asthma has been confirmed, clinicians can then start to move patients along the correct care pathway to ensure that they are accessing the treatment they need to control their asthma. For those diagnosed with severe asthma, this could mean being eligible for one of the new biologic drugs known as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). These have already led to dramatic improvements in the health of a many people with severe asthma.

MONOCLONAL ANTIBODIES

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are drugs that have been developed to target specific biological markers in order to reduce inflammation in the lungs.

How mAbs work

Biologic drugs are genetically engineered proteins that have been developed for people with severe asthma. They are based on the understanding that asthma, far from being a single condition, has many clinical manifestations (phenotypes), which arise by specific mechanistic pathways (endotypes).

In eosinophilic asthma, small proteins (Interleukin [IL]25, IL33, Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin[TSLP]) are released in response to air pollutants or microbes. These bind to receptors on T2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), activating them to produce the T2-associated proteins IL5 and IL13, which lead to the production of eosinophils, airway hyper-reactivity and mucous hypersecretion.

In allergic asthma, exposure to an allergen causes the immune system to produce IgE, a specific type of antibody (protein). IgE locks onto the surface of immune cells, causing them to release chemicals that set off the allergic reaction (including producing eosinophils). These chemicals trigger symptoms like coughing, shortness of breath, and wheezing.

Eosinophilic inflammation in the airways is the common feature of both these asthma phenotypes. Eosinophils are a type of white blood cell that normally comprise less than 5% of white blood cells in the peripheral blood.12 However, in response to T2 helper T-cell-mediated inflammation, they can build up in excess and cause inflammation.

There are currently two types of these biologic drugs available and they both treat Type 2 (T2) inflammation-driven severe asthma. One, omalizumab, targets the immune system protein, IgE, to help prevent the allergic reaction, and the others, mepolizumab, reslizumab and benralizumab, target IL-5 to inhibit the excess production of eosinophils and to treat ‘eosinophilic’ asthma.11

Current availability of mAbs

There are currently four mAbs approved by NICE for England, Wales and Northern Ireland and two approved by the Scottish Medicine Consortium (SMC) for Scotland. However, some people may have to try multiple different mAbs to find the one that works for them and for some they may not work at all. Most require monthly visits to a specialist asthma clinic for an injection, however self-injectable versions are in the pipeline. NICE/SMC have set strict criteria for which patients can receive these drugs. This is partly to ensure that the patients with the right phenotype of asthma get the medicines they need, but also that the medicines are used in the most cost-effective way. These criteria may include number of exacerbations in the last year (or courses of OCS), a high eosinophil blood count or a diagnosis of confirmed allergic asthma.

Currently, there is a lack of long-term evidence for mAbs and it is unclear how long people will have to remain on them. The good news is that as more mAbs become available the greater the chances someone with severe asthma has in getting the right one for them. However, without referral to a specialist clinic those with severe asthma will never get that opportunity.

There is plenty of evidence that these drugs can be truly life-changing for people with certain types of severe asthma, stopping their reliance on OCS and keeping them out of hospital.13

Case study 2

Rachel, 43, was frequently in hospital due to asthma attacks and the only treatment that worked for her was high dose OCS. She suffered from severe side effects including weight gain and mood swings. It wasn’t until she was referred to a specialist asthma clinic and prescribed mepolizumab that her life was transformed. She went from being unable to exercise or go out with her friends because of her asthma, to leading a normal life and even climbing Ben Nevis!

Referral to a specialist asthma clinic can still be beneficial for patients who have difficult rather than severe asthma. People with difficult asthma can have complex needs and may benefit from a multidisciplinary team better equipped with the right tools to deal with mental health, weight management, smoking cessation and other comorbidities. It is often not possible in primary care to distinguish between this group and those with severe asthma; therefore, referral is crucial in getting patients the correct diagnosis and best possible treatment.

SUMMARY

Primary care practitioners can make a real difference to people with difficult or severe asthma by being more aware of those who are suffering uncontrolled symptoms, despite optimal treatment and good adherence, and referring them at the right time.

There are still people with asthma not getting the right level of support for their condition, and whose needs are not being met. By referring these patients and addressing their poorly-controlled asthma, primary care practitioners can help improve their quality of life and reduce the burden their asthma places on them, their family and healthcare services. There is hope for patients once they are referred onto the right care pathway, including potential access to life-changing mAbs.

- We would like to thank Dr Noel Baxter, Dr Andrew Whittamore and Natalie Harper for their valuable contributions to early drafts of this article.

REFERENCES

1. King’s Fund. Understanding pressures in general practice. 2016. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/Understanding-GP-pressures-Kings-Fund-May-2016.pdf

2. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Quality and Outcomes Framework Indicators. Standards & Indicators, 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/standards-and-indicators/qofindicators

3. Hekking P-PW, Wener RR, Amelink M, et al. The prevalence of severe refractory asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Apr;135(4):896–902.

4. Allen O. Slipping through the net: The reality facing patients with difficult and severe asthma. Asthma UK; 2018. https://www.asthma.org.uk/6fc29048/globalassets/get-involved/external-affairs-campaigns/publications/severe-asthma-report/auk-severe-asthma-gh-final.pdf

5. Kerkhof M, Tran TN, Soriano JB, et al. Healthcare resource use and costs of severe, uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma in the UK general population. Thorax. 2018 Feb;73(2):116–24.

6. Broadbent C, Pfeffer P, Steed L, Walker S. Patient-reported side effects of oral corticosteroids. Eur Respir J. 2018 Sep 15;52(suppl 62):PA3144.

7. Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills: The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD), 2014. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills

8. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Asthma Quality standards, 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs25

9. Primary Care Respiratory Society (PCRS). Asthma Slide Rule, 2019. https://www.pcrs-uk.org/resource/asthma-slide-rule

10. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, British Thoracic Society. British guideline on the management of asthma: a national clinical guideline, 2016. https://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-153-british-guideline-on-the-management-of-asthma.html

11. Bousquet J, Brusselle G, Buhl R, et al. Care pathways for the selection of a biologic in severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2017 Dec 1;50(6):1701782.

12. Kostikas K, Brindicci C, Patalano F. Blood Eosinophils as Biomarkers to Drive Treatment Choices in Asthma and COPD. Curr Drug Targets. 2018 Dec;19(16):1882–96.

13. Brightling CE. Clinical trial research in focus: do trials prepare us to deliver precision medicine in those with severe asthma? Lancet Respir Med. 2017 Feb 1;5(2):92–5.

Related articles

View all Articles