Taking the initiative in asthma care: the 2019 Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines

Beverley Bostock-Cox

Beverley Bostock-Cox

RGN MSc MA QN

Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery, Moreton in Marsh

Asthma Lead, Association of Respiratory Nurse Specialists

Education Lead, Education for Health, Warwick

The latest GINA guidelines offer a major shift in the initial prescribing for people with asthma, which may appear controversial but is supported by evidence. But will it change UK practice?

April 2019 saw the publication of the latest update to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines, with the first page stating that this was a ‘major change in…strategy’.1 This big change will be discussed in this article, but it’s a timely reminder that even though the UK has two key (and contrasting) asthma guidelines from the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN)2 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),3 international guidelines such as GINA can give another perspective on how asthma is diagnosed and treated.

In this article, we will discuss:

- The different views on asthma diagnosis taken by each guideline

- Their contrasting approaches to asthma management

- The major change advocated in the GINA guidelines

- The impact that different guidelines can have on clinicians treating people with asthma

DIAGNOSING ASTHMA

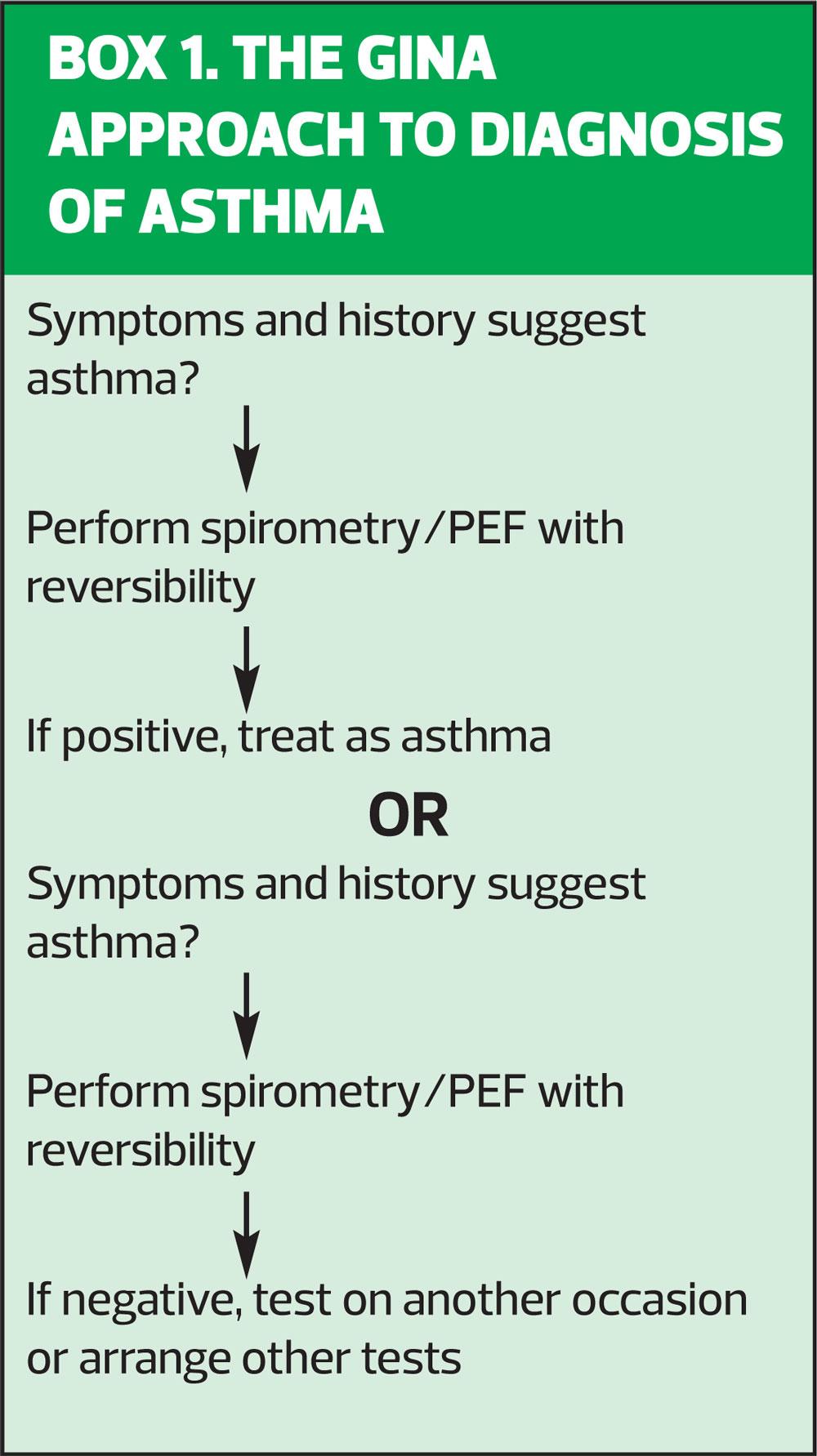

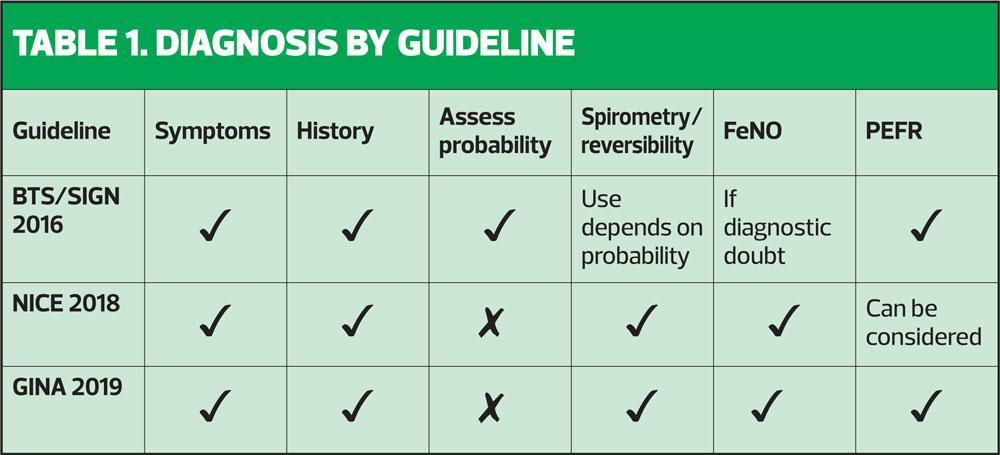

The NICE asthma guidelines recommended that all patients suspected of having asthma should have a history taken, a full examination, fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) level measurements and spirometry with reversibility, ideally carried out at the first presentation of symptoms.3 These could be considered to be aspirational, as few people have access to or training in FeNO testing and many clinicians would struggle to do all of this in a standard 10-minute appointment. In contrast, the BTS/SIGN guidelines recommend taking a thorough history to establish the probability of asthma and proceeding straight to a trial of treatment (inhaled corticosteroid [ICS]) if there is a high probability of asthma.2 In cases where there is intermediate probability and diagnostic doubt, objective tests should be carried out, with spirometry considered to be the gold standard but with peak flow readings or FeNO also being considered to be acceptable, depending on the guideline (see Table 1). The GINA guidelines say that the key features of asthma are the symptoms plus variable expiratory airflow limitation (p8) and thus the diagnosis must demonstrate both of these elements.1 (Box 1)

Spirometry

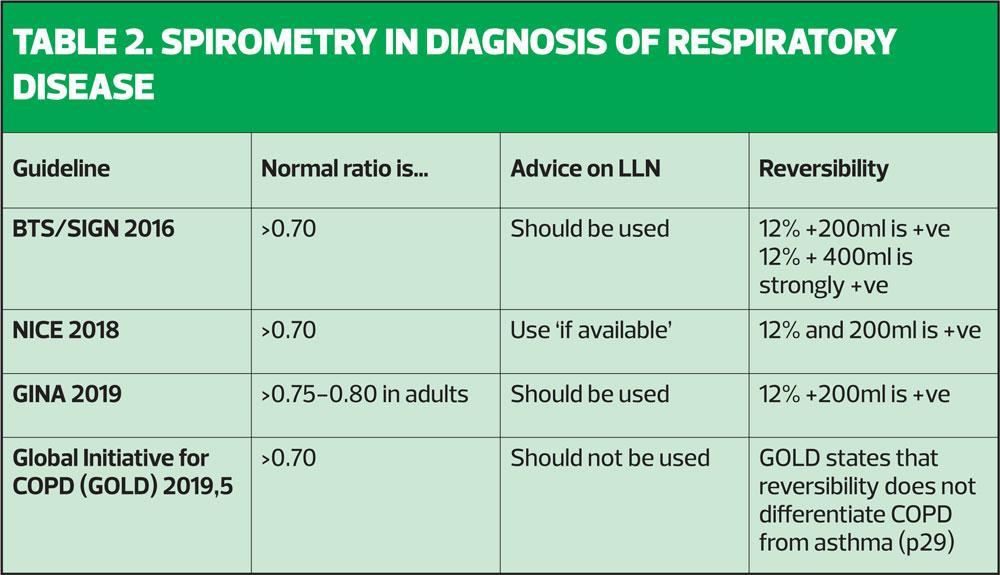

Much has been written about using spirometry as a tool which can support a diagnosis of asthma, COPD or other respiratory conditions. It is essential to remember that spirometry is a test which, when performed correctly, should demonstrate a pattern (normal, obstructive, restrictive or combined) and, in the case of an obstructive pattern, a response to treatment (reversible or irreversible). It does not give the diagnosis, but will give objective evidence about lung capacity and patterns of airflow.4 So, the diagnosis of respiratory disease is made first and foremost on the history (symptoms, triggers, family history, atopy, occupation, smoking, for example) which may then be supported by objective testing, including spirometry, peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) and FeNO testing. On that basis, then, there must be clearly defined parameters for saying that a test is normal or abnormal. In reality, however, the guidelines give different views on what constitutes a normal ratio, whether fixed ratios or lower limits of normal (LLN) should be used, and what should happen if the patient's lung function tests do not align with their history and presentation.

So what does each guideline say about spirometry in the diagnosis of respiratory disease? See Tables 1 and 2.

On page 13 of the full BTS/SIGN 2016 asthma guidelines,2 the unpredictable nature of spirometry is discussed, pointing out that in primary care patients with intermittent asthma symptoms, only 16-39% of patients showed obstructive spirometry and positive bronchodilator reversibility was demonstrated in only 15–17% of patients. This was in contrast to patients admitted with active, acute asthma where 83% of patients showed airflow obstruction. (That does beg the question about what exactly was going on in the 17% of patients admitted with ‘acute asthma’ where the spirometry apparently did not show obstruction). BTS/SIGN states that as spirometry has a false negative rate of at least 50%, normal spirometry does not rule out asthma and states that although spirometry is useful for confirming the diagnosis of asthma, it is not sufficiently specific to rule it out (p27). However, the guidelines states that in a symptomatic patient, peak flow monitoring may provide objective evidence of variability (p24) and GINA agrees with this view. Ultimately, BTS/SIGN suggests that we should compare diagnostic test results when the patient is asymptomatic with when they are symptomatic to detect variation. However, in the meantime, a trial of treatment with an ICS is probably going to give us the answer that objective testing with spirometry has not. For a test where the parameters seem rather vague, and where guidelines repeatedly state that both normal and abnormal results are open to debate in the clinical setting, spirometry seems to take up an inordinate amount of training time and budget.

Whether spirometry or peak flow is used for assessing lung function, GINA recommends that it should be checked at diagnosis, 3-6 months after starting treatment and ‘periodically’ thereafter; in fact, GINA states that most people should have it checked every 1-2 years (p13).1

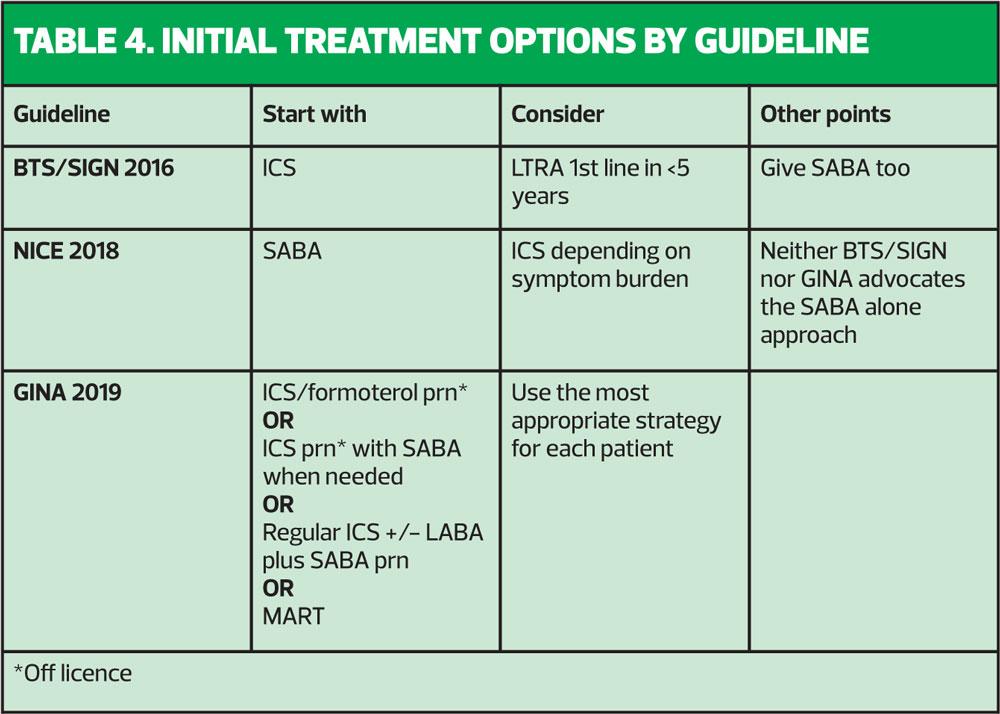

TREATMENT OPTIONS – BTS/SIGN, NICE and GINA

BTS/SIGN has advocated immediate treatment with an ICS since 2016.2 NICE states that a short acting beta2 agonist (SABA) may be tried but if the patient is symptomatic three times a week or more or having night symptoms, or if their symptoms are not ‘controlled’ (sic) with a SABA, then an ICS should be considered.3 Stepping up would involve adding a long acting beta2 agonist (LABA) if following BTS/SIGN guidelines whereas NICE would advocate adding a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) on the grounds of cost. However, this leaves patients at potential risk if they decide to use their LTRA pill without their ICS inhaler, as opposed to being on a combination inhaler with an ICS and a LABA in one, as advised by BTS/SIGN. There are many advantages to having an ICS/LABA combination treatment both as a fixed dose and as a maintenance and reliever therapy regimen (MART): convenience, only needing one device and ensuring that the asthma treatment (the ICS) is given every time the reliever (the LABA) is taken. Furthermore, the LABA will potentiate the ICS, meaning that each puff of an ICS taken with a LABA has more impact than if it were taken alone.6 These two guidelines seem to give conflicting advice, then. So where do the GINA guidelines weigh into the debate?

THE MAJOR CHANGE

GINA guidelines state that using a SABA alone in mild asthma is linked to an increased risk of major exacerbations.1 This was also seen in the National Review of Asthma Deaths.7 As a result, the guidelines committee has said that in people with so-called ‘mild’ asthma an ICS should always be prescribed. So this concurs with BTS/SIGN.2

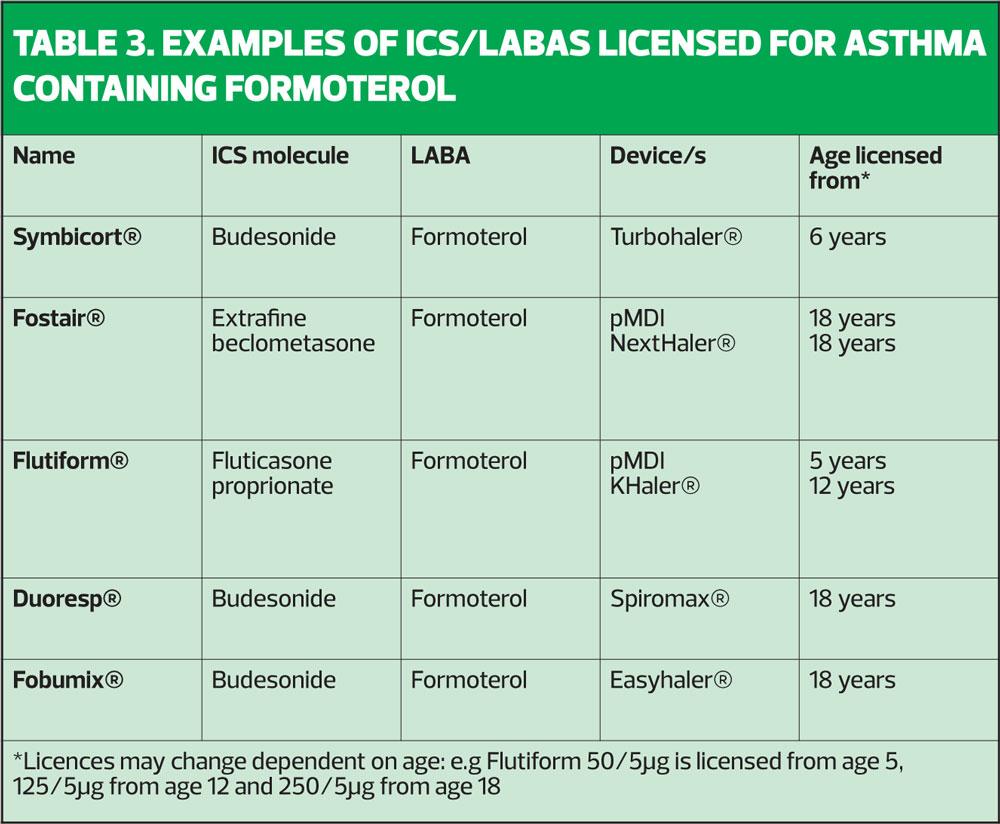

It is worth remembering that in NRAD, of those people where severity of asthma could be ascertained, almost 1 in 10 people who died from asthma had mild disease, with 39% having moderate and 49% having severe asthma.7 Describing asthma as ‘mild’ to patients (or parents) could therefore be construed as falsely reassuring. However, the GINA committee has said that because asthma which might previously have been called ‘mild’ is linked to exacerbations (and potentially death) ICS-based therapy should always be encouraged, given either as a daily low dose treatment or on an ‘as required’ basis, combined with a LABA (specifically formoterol) to treat asthma using an approach which is driven by symptoms.1 The GINA recommendation for mild asthma in people age 12 and above is to use a low dose formoterol-containing ICS/LABA, so that every time patients have any asthma symptoms, they use this inhaler to treat symptoms but with each puff they also get some ICS, which will treat the underlying inflammation.1 (Table 3)

The problem with this approach (and GINA acknowledges this), is that there is no ICS/LABA that is licensed to be used this way.

It should be noted that any combination inhaler that has salmeterol as the LABA will not be suitable for this approach as the salmeterol would take too long to have an effect on symptoms. The same is true of vilanterol.8,9

GINA says that the reason for this change in strategy is to reduce serious asthma exacerbations and death and to avoid establishing a reliance on the SABA early in the course of the disease.1

Medico-legally, it is important to note that off-licence prescribing should only be implemented when there is no suitable licensed option and only then if the patient has agreed to this approach. The discussion, explanation and agreement should be documented in the notes.10

On the gov.uk website there is the following advice for prescribers regarding off-licence prescribing:

You should:

- Be satisfied that an alternative, licensed medicine would not meet the patient’s needs before prescribing an unlicensed medicine

- Be satisfied that such use would better serve the patient’s needs than an appropriately licensed alternative before prescribing a medicine off-label.

Before prescribing an unlicensed medicine or using a medicine off-label you should:

- Be satisfied that there is a sufficient evidence base and/or experience of using the medicine to show its safety and efficacy

- Take responsibility for prescribing the medicine and for overseeing the patient’s care, including monitoring and follow-up

- Record the medicine prescribed and, where common practice is not being followed, the reasons for prescribing this medicine; you may wish to record that you have discussed the issue with the patient

Best practice for communication includes:

- Giving patients, or those authorising treatment on their behalf, sufficient information about the proposed treatment, including known serious or common adverse reactions, to enable them to make an informed decision

- Where current practice supports the use of a medicine outside the terms of its licence, it may not be necessary to draw attention to the licence when seeking consent. However, it is good practice to give as much information as patients or carers require or which they may see as relevant

- Explaining the reasons for prescribing a medicine off-label or prescribing an unlicensed medicine where there is little evidence to support its use, or where the use of a medicine is innovative

Healthcare professionals have a responsibility to help monitor the safety of medicines in clinical use through submission of suspected adverse drug reactions to the MHRA and CHM via the Yellow Card Scheme. Such reporting is equally important for unlicensed medicines or those used off-label as for those that are licensed.

Is there any evidence to support GINA’s approach?

GINA states that patients who are having symptoms less than twice a month are unlikely to take a daily ICS. Poor adherence can be an issue in other patient groups, too, particularly those with mild asthma, leaving them at risk of exacerbations. A study by O’Byrne et al,11 using as required budesonide/formoterol combination inhaler showed a 64% reduction in severe exacerbations when compared with using a SABA alone. The same study demonstrated non-inferiority for severe exacerbations when compared with a regular ICS regimen. The same non-inferiority result was shown in a separate study by Bateman et al.12 Previously, this approach had been shown to be equally effective as regular ICS therapy in people with exercise induced symptoms.13 As required ICS/formoterol therapy is also considered by GINA to be a good option for people who have had no symptoms on a regular low dose ICS and need to step down (p25).1

ASSESSING CONTROL, STEPPING UP AND STEPPING DOWN

Each guideline recommends using key questions and assessments of inhaler use (particularly SABA use) as a marker of control. GINA advises clinicians to ask about symptoms in the past 4 weeks, including daytime, night time and activity-related symptoms, along the lines of the Royal College of Physicians’ 3 questions structure,14 but with an extra question about reliever use. GINA deems using a reliever more than twice a week to be too much, whereas BTS/SIGN and NICE advocate a review of inhaled therapy if the reliever is used three times a week or more. Both GINA and BTS/SIGN advocate adding in a LABA whereas NICE suggests trialling an LTRA as this is a cheaper (but less clinically effective) option. No change should be made without checking inhaler technique and adherence.

Stepping down is advised in the BTS/SIGN and GINA guidelines after around 3 months of good control. NICE recommends stopping the ICS after 8 weeks to check that any resolution of symptoms is truly reflective of the impact of the treatment and not purely by coincidence.3 Assessment of and advice on how and when to trial coming off an ICS varies. However, GINA does not recommend stopping the ICS completely but recommends moving to ICS/formoterol prn (when necessary) instead.

ESSENTIAL SKILLS FOR PATIENTS AND CARERS

GINA states that people with asthma (or their carers) should be supported to develop essential skills in asthma management. This should be based around information about asthma, inhaler technique, adherence, written asthma action plans, self-monitoring and regular review (p15).1

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The GINA guidelines offer an innovative but pragmatic approach to treating inflammation in mild asthma where adherence to daily doses of ICS may be poor.1 However, the lack of licence to use ICS/formoterol inhalers in this way could be problematic for some prescribers. In this situation, it is important to take each situation on a case by case basis, recognising when prescribing off licence but with an evidence base for doing so, would better align with the Nursing and Midwifery Code of Conduct15 than not doing so. Issues such as putting the patient first, practising effectively and preserving safety may be best served by prescribing in this way in some cases. The skill of the clinician is in deciding the best approach after discussion with the patient, thus preserving the concept of autonomy.

SUMMARY

The new GINA guidelines offer a novel way of managing mild asthma in people over the age of 12. This approach adds to the existing body of opinion and evidence demonstrated in the BTS/SIGN and NICE guidelines. Later this year the new BTS/SIGN asthma update will be published which will be developed in collaboration with NICE. It will be interesting to see how they approach this issue. In the meantime, clinicians should see these different strategies to asthma diagnosis and management as an opportunity to tailor asthma care to the individual, by cherry picking what works best for each individual case.

REFERENCES

1. Global Initiative for Asthma. Asthma management and prevention, 2019 https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/GINA-2019-main-Pocket-Guide-wms.pdf

2. British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Asthma guidelines, 2016 https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/asthma/btssign- asthma-guideline-2016/

3. NICE NG80. Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management, 2017 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80

4. Primary Care Commissioning, Quality Assured Diagnostic Spirometry, 2013 https://www.pcc-cic.org.uk/sites/default/files/articles/attachments/spirometry_e-guide_1-5-13_0.pdf

5. Global Initiative for COPD: 2019 Report https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GOLD-2019-v1.7-FINAL-14Nov2018-WMS.pdf

6. Chauhan BF, Ducharme FM. Addition to inhaled corticosteroids of long-acting beta 2 agonists versus anti-leukotrienes for chronic asthma (Review) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014;1:CD003137 https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003137.pub5/epdf/standard

7. Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills: The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD), 2014 https://www.asthma.org.uk/293597ee/globalassets/campaigns/nrad-full-report.pdf

8. Drugs.com. Salmeterol, 2019 https://www.drugs.com/ppa/salmeterol.html

9. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Fluticasone Furoate/Vilanterol, 2016 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK409764/

10. MHRA. Off-label or unlicensed use of medicines: prescribers’ responsibilities, 2014. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/off-label-or-unlicensed-use-of-medicines-prescribers-responsibilities

11. O’Byrne PM, FitzGerald MJ, Bateman ED, et al. Inhaled Combined Budesonide–Formoterol as Needed in Mild Asthma N Engl J Med 2014;378(20):1865-1876

12. Bateman ED, Reddel HK, O’Byrne PN, et al (2018) As-Needed Budesonide-Formoterol versus Maintenance Budesonide in Mild Asthma N Engl J Med 2018;378(20):1877-87

13. Lazarinis N, Jørgensen L, Ekström T, et al. Combination of budesonide/formoterol on demand improves asthma control by reducing exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Thorax 2014;69:130-136.

14. Thomas M, Gruffydd-Jones K, Stonham C, et al. (2009) Assessing asthma control in routine clinical practice: use of the Royal College of Physicians ‘3 Questions’. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:83-8 http://www.nature.com/articles/pcrj200845

15. Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code. Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates. 2015 (updated 2018). https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/

Related articles

View all Articles