Moving on up – combination inhalers and beyond

Beverley Bostock

Beverley Bostock

RGN MSc MA QN

Advanced Nurse Practitioner, Mann Cottage Surgery

Education Facilitator Devon Training Hub

Policy Forum Member, Primary Care Respiratory Society

Asthma Lead, Association of Respiratory Nurse Specialists

Practice Nurse 2021;51(2):22-26

Combination and triple therapies can improve outcomes in people with asthma, but which drug and device is the right one for your patient?

Asthma is a condition that is largely managed in primary care, often by general practice nurses (GPNs). Guidelines from the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN) and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) both highlight the importance of combination inhalers in the management of asthma,1,2 but licences have recently been awarded for triple therapies too. In this article we discuss why combination and triple therapies can improve outcomes for people with asthma and offer guidance on how to select the most appropriate inhaled drug and device.

By the end of this article readers should be able to:

- Recognise where combination therapies fit into asthma management strategies

- Assess the impact of the device on improving outcomes

- Consider the range of molecules that are available in combination therapies for asthma

- Review the decision-making process when selecting a drug and device

Further information on all of the drugs mentioned in this article can be found at the Electronic Medicines Compendium website: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/ and information on how to use the devices discussed can be found at the Asthma UK website: www.asthma.org.uk/advice/inhaler-videos

THE ROLE OF COMBINATION THERAPIES IN ASTHMA MANAGEMENT

The mainstay of managing the pathophysiological changes that occur in asthma is inhaled corticosteroids (ICS). Anyone with a current diagnosis of asthma should be treated with an ICS.1,2 GINA guidelines recommend that treating people with a asthma with an ICS combined with a fast-acting long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) is the best way to address underlying inflammation and symptoms.2 LABAs have been shown to support the action of the ICS molecule in a way that makes using a combination superior to using an ICS alone.3 GINA no longer advocates the use of a short-acting beta2 agonist (SABA) for symptom relief; they recommend using an ICS/LABA even in patients with infrequent symptoms, but on an ‘as required’ basis in place of the SABA. It is important to note, however, that there are no ICS/LABAs licensed to use in this way in the UK at present. In essence, then, BTS/SIGN guidelines recommend using an ICS/LABA after an ICS alone if symptoms are inadequately controlled,1 whereas GINA guidelines recommend considering an ICS/LABA for anyone with asthma, although current licenses also refer to using combinations as a ‘step-up’ treatment only.

ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF THE DEVICE ON IMPROVING OUTCOMES

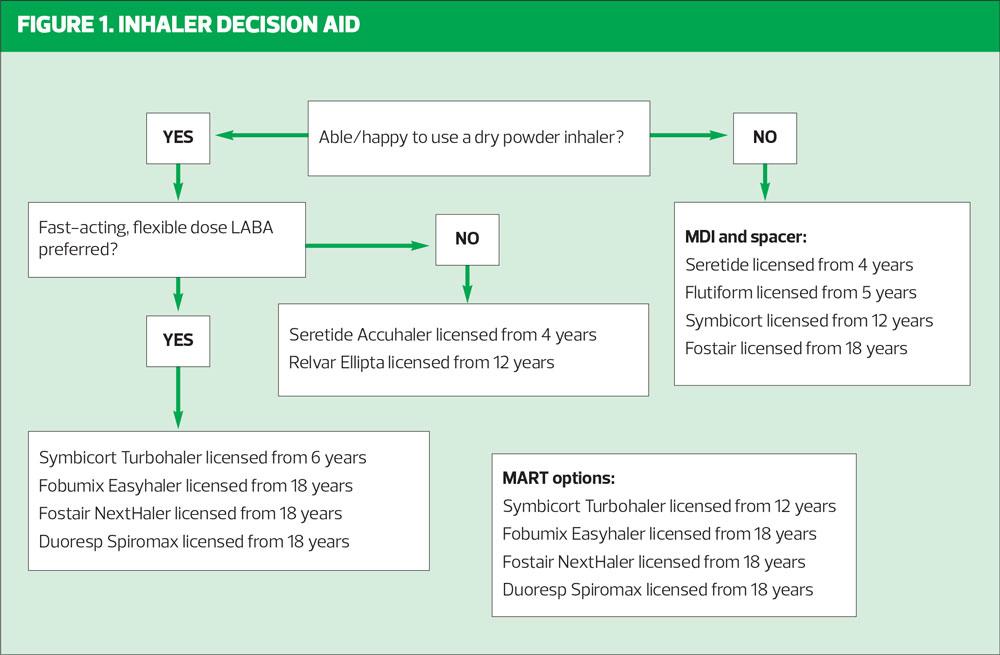

There are three main inhaler types with which GPNs should be familiar. The most commonly prescribed device in the UK is the metered dose inhaler (MDI), with the dry powder inhaler (DPI) making up ground in recent years, partly because of environmental concerns. DPIs have a much lower environmental impact than MDIs and so NICE has recommended offering a DPI as the first line option for patients who need inhaled therapy, unless a DPI is not suitable.4 However, the fact remains that the most expensive and least green inhaler option is the one that is not used correctly and an exacerbation with an unplanned hospital admission will have a significant impact on resources, so financial, environmental and clinical concerns should all be considered. Less often prescribed but still a useful adjunct to the inhaler armoury, are the breath actuated (or activated) inhalers (BAIs) such as the Easibreathe. There is a wealth of research on which inhaler device is ‘best’ for patients, but the truth is that finding the optimal match for a patient to a device is a very individual thing. Some people will love a device that others dislike, some people find certain inhaler device features difficult to use while others will prefer that same inhaler for precisely the same features. Some will dislike the taste of an inhaler while others are concerned that theirs has little or no taste. It is worth asking people what their ideal inhaler would be like and listen to the response.

However, it is not just patient preference that matters, it is the ability to use the device which is most important, otherwise it is the equivalent of giving a sick child paracetamol on a fork. In simple terms, it is important to know whether a patient can take the fast, deep breath needed to get the most from a dry powder inhaler or whether they are better suited to the slow, steady intake of breath needed for an MDI and spacer, which requires less patient effort. It is also necessary to assess whether the patient has the level of dexterity needed to prepare and prime a device. Usmani et al have developed an algorithm which reflects some of these points and which can be downloaded here: https://www.guidelines.co.uk/respiratory/inhaler-choice-guideline/455503.article

Teaching correct inhaler technique is essential, including in the pandemic when video consultations have taken over from face to face appointments. Demonstrating and observing inhaler technique remotely and linking patients up to the Asthma UK inhaler videos will ensure good technique is learnt and maintained.

MOLECULES IN COMBINATION INHALERS FOR ASTHMA

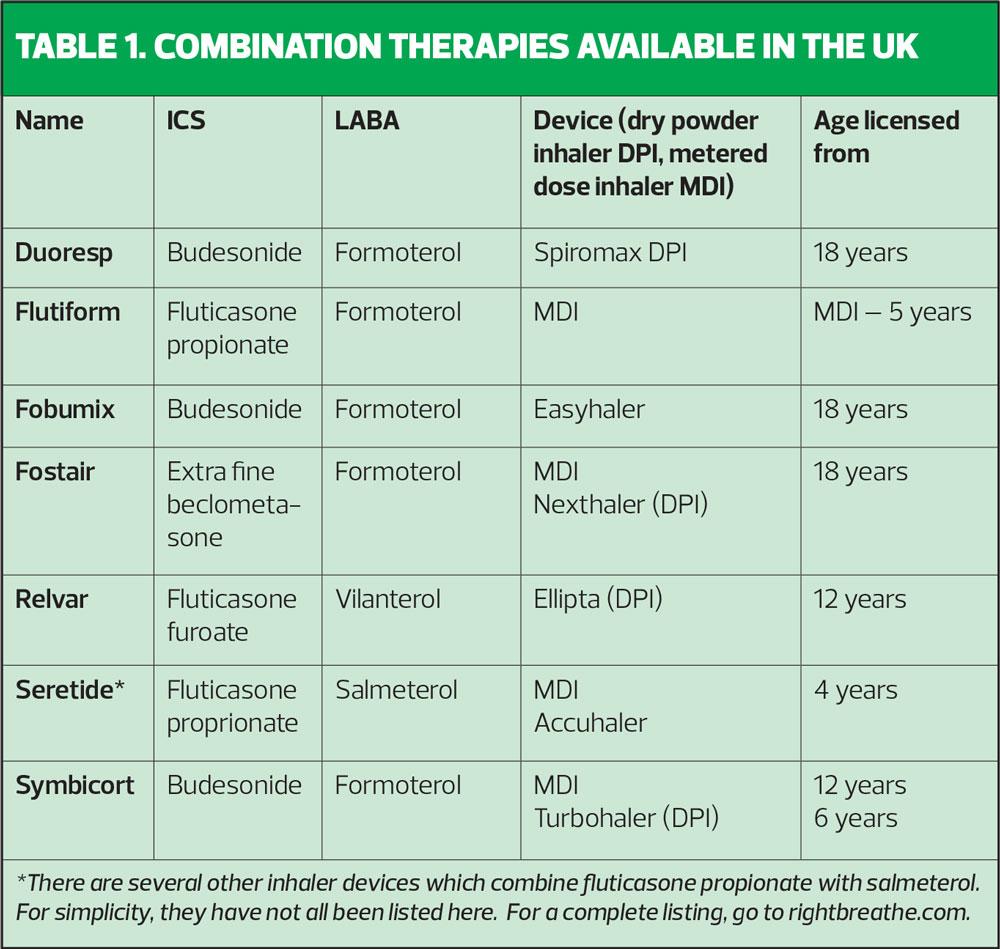

Examples of combination therapies available in the UK are shown in Table 1.

With both GINA guidelines and BTS/SIGN highlighting the role of maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) in the management of asthma, it is worth considering which of these inhalers is licensed to use in that way. Only formoterol-containing inhalers can be used in line with MART as this molecule works to relieve symptoms within 1-3 minutes. Both vilanterol and salmeterol take too long to act to allow them to be used for symptom relief.

DECISION-MAKING IN DRUG AND DEVICE SELECTION

It is worthwhile considering the different stakeholders and drivers involved in choosing inhalers. There are guidelines and formularies, health outcomes, costs to the NHS, costs to the patient, and also the influence of the clinician who needs to understand how the inhaler works and how to teach it. An acronym I use in my own practice is to think of the ‘PEACH’ when teaching inhaler technique: Prime – Exhale – Actuate – Correct inspiratory flow – Hold the breath. Although devices are all different, users will need to follow a similar ‘PEACH’ procedure to get the most from their device. Patient involvement in choosing an inhaler device is important in ensuring that they feel connected to it and are keen to use it.

When seeing people via remote consultations, it is possible to generically assess inspiratory flow by asking them to breathe in fast and hard then slowly and steadily and ascertain which feels better to them. A breath in for an MDI should take between 4-5 seconds.5 If the individual is only taking 1-2 seconds to demonstrate their technique, a DPI is probably better for them.

Device

The ability to take a fast, deep breath in will suggest that a DPI may be suitable and NICE recommends DPIs as a first line option if (and only if) suitable for the individual being treated. Device consistency is important, made simpler by the MART approach which only requires the use of one type of device. There needs to be a move away from prescribing MDIs as the default device when initiating an ICS as this will ensure patients are familiar with DPIs from the start. However, this is only appropriate if the patient can use a DPI.

Drug

Formoterol is a flexible, fast-acting molecule which allows the medication to be taken in response to the severity of symptoms e.g. with Fostair, Fobumix, Symbicort where patients can take 1 puff bd, two puffs bd or one puff bd and, where needed, extra puffs as required (MART). The other LABAs used in combination inhalers (salmeterol and vilanterol) do not have this flexibility and have slower onset of action.

With respect to the ICS dose, it is important to recognise which ICS are standard strength, which are higher potency, and which have extra-fine particles, as these aspects affect the dose being taken.

- Budesonide – this is a standard ICS, with no dose ‘translation’ needed

- Fluticasone propionate – this is a more potent molecule so give half the dose of budesonide

- Fluticasone furoate – 92mcg = low/medium dose ICS, 184mcg = high dose ICS

- Beclometasone extra-fine particle – the increased delivery to the airways via the extra-fine particles means that 100mcg of extra-fine beclometasone in Fostair = 250mcg of a standard ICS as seen in budesonide

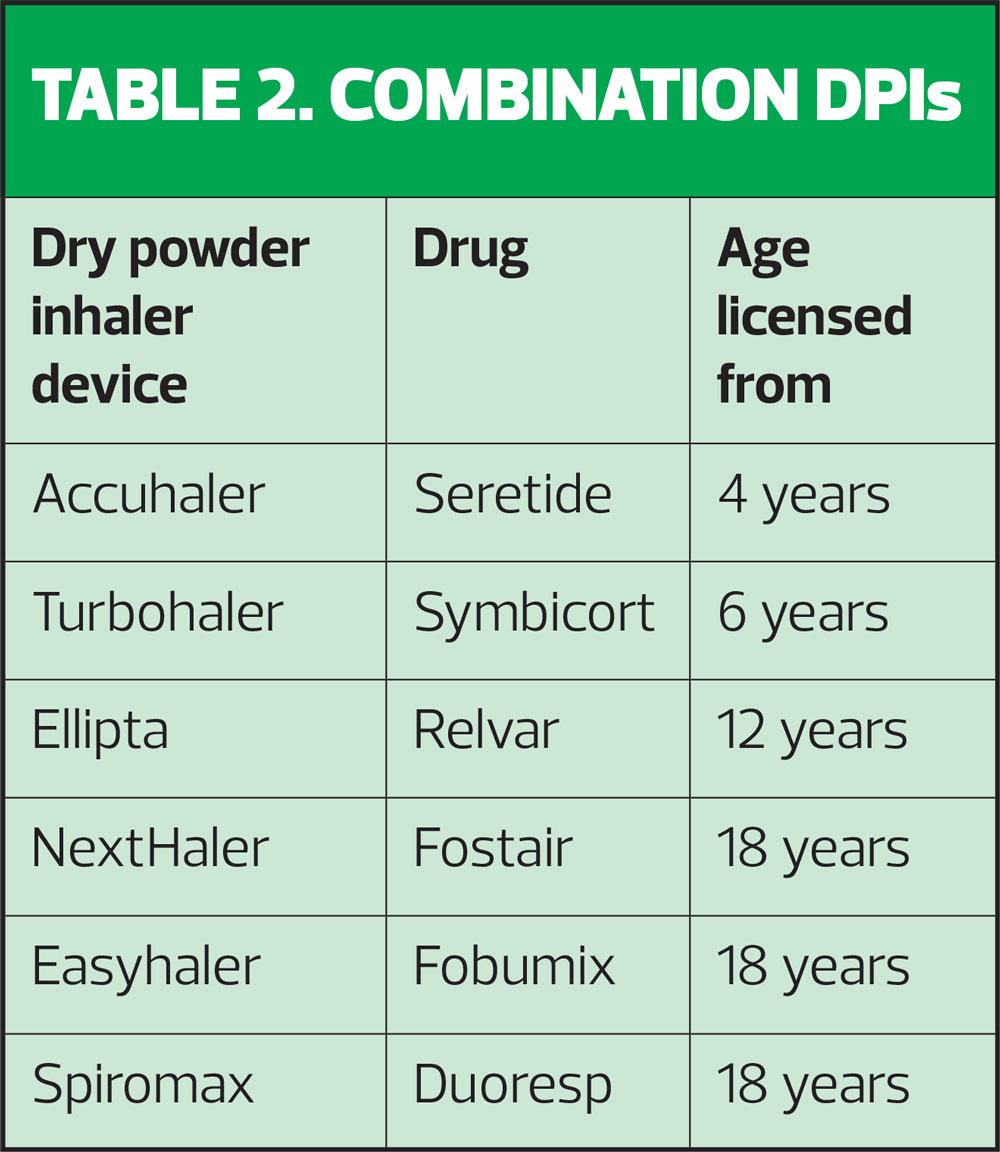

AGES AND LICENCES

Younger children should always be offered an MDI and spacer but as they get older, some children will be able to use DPIs. It is important to ensure that the device is licensed for children (Table 2) and that the child can use it, irrespective of what the licence says.

For more information about how each of these devices work, go to the Asthma UK website: https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/inhaler-videos

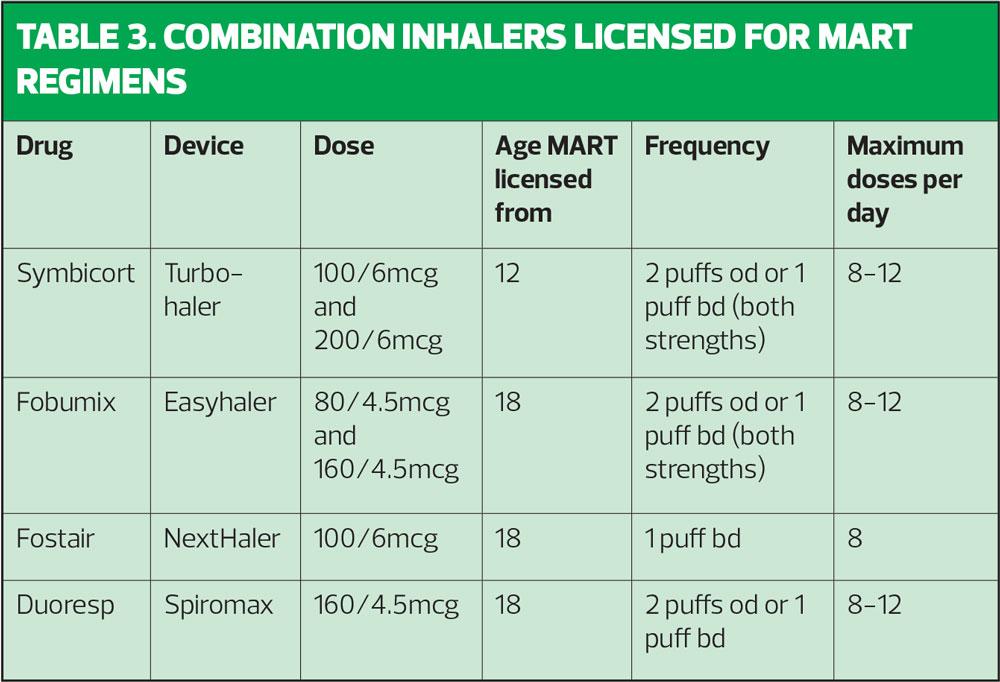

MART DOSE REGIMES

It is important to know what the licensed recommendations are when using MART. Table 3 spells these out. Clinicians may not always be aware that some formoterol-containing inhalers can be used once daily (as well as the usual twice daily dosing) and this information is included here.

With respect to the use of MDIs for MART, Fostair and Symbicort are suitable and licensed. Fostair MDI is licensed from age 18 and is used at the same dose as the NextHaler. The Symbicort MDI was previously only licensed for COPD but can now be prescribed for asthma (100/3mcg dose) in people aged 12 and above as both maintenance therapy (2 puffs bd or 4 puffs od) and maintenance and reliever therapy, where 2 extra puffs should be taken to relieve symptoms, up to a maximum of 16 a day, although 24 may be taken in exceptional circumstances.

CASE STUDY: ROBIN, AGE 34

Robin needs to step up to a combination inhaler for his asthma. He is currently on 200mcg standard beclometasone bd via a MDI and spacer but is keen to move to a DPI. He demonstrates good inhaler technique.

Robin prefers a DPI so as he is over 18, all of the inhalers in Table 2 are licensed options. By going for the flexible LABA molecule formoterol, the choice of inhalers reduces down to four, as neither Seretide nor Relvar contain this molecule. Robin thinks he would prefer to use a MART approach to manage his asthma and all four options are licensed for this. It is important to recognise that MART is not a licensed option for Flutiform.

Robin now has four devices to choose from which are all DPIs containing formoterol and which can be used as maintenance and reliever therapy. The final choice should ideally be made by Robin, but clinicians may decide to refer to their local formulary for recommendations before supporting Robin with his final selection. It may be that only two of the four devices identified are recommended by the local prescribing committee, for example. Nonetheless, clinicians should always be aware of their legal and ethical duties to match the right treatment to the right patient, optimising benefit and minimising harm.6

CASE STUDY: SAM, AGE 12

Sam is on a combination therapy via a DPI for his asthma, which he uses at a fixed dose of 2 puffs bd. He has good technique. He is an active and competitive sportsman and occasionally gets exercise-induced symptoms. He keeps a blue inhaler to relieve symptoms during or after playing sport. His mum, who also has asthma, uses the MART system and wants to know if Sam can try this too.

As Sam’s asthma is generally well controlled with only the occasional use of a SABA, MART would be a suitable option for him. The GINA guidelines would certainly endorse this approach, as these guidelines no longer recommend the use of SABAs for symptom relief.2 In Sam’s case there is a licensed option for MART in children age 12 and above, which is Symbicort via the Turbohaler. No other combination is currently licensed to use as MART below the age of 18, and no combination is licensed to use as MART below the age of 12.

TRIPLE THERAPIES FOR ASTHMA

Although guidelines do not routinely refer to the use of long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) in asthma, Spiriva has been licensed as an add-in therapy for anyone age 6 and above who is not fully controlled and has had an exacerbation on a medium dose of ICS/LABA. These patients might require referring to a severe asthma clinic if they are adherent to prescribed medication, have good technique and other co-morbid conditions such as reflux or post-nasal drip have been excluded. However, the addition of a LAMA to an ICS/LABA could be considered while waiting for a severe asthma appointment.

Trimbow, a triple therapy previously licensed for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, has recently been given a licence for asthma. The indications for Trimbow use in asthma is for maintenance treatment in adults not adequately controlled with a combination of a medium dose ICS/LABA and who have experienced one or more asthma exacerbations in the previous year. The dose is 2 puffs bd and Trimbow is not licensed for MART. There are two dose options for Trimbow when treating asthma: 87/5/9 micrograms or 172/5/9 micrograms. The decision regarding which dose to use will be based on the individual patient’s needs. Other triple therapies may be available in the future.

CONCLUSION

Many patients with asthma will benefit from using combination therapies consisting of an inhaled corticosteroid and a long-acting beta2 agonist, as this can improve overall control, reduce the risk of exacerbations and simplify treatment regimes, especially when used as maintenance and reliever therapy. With international guidelines increasingly recognising the need to improve asthma treatment to reduce asthma attacks and deaths, clinicians need to be familiar with what is available, based on patient need and drug licences. Effective delivery of the drug is essential so device choice based on assessment of inhaler technique should be central to the decision-making process. Inhaler technique should be reviewed at every opportunity. In remote consultations this can include assessment via video and also by linking the patient to the Asthma UK inhaler videos, for example via an Accurx message. Once the most appropriate device has been chosen, careful consideration should be paid to the ICS dose and potency and also to the LABA, with regard to the onset of action. BTS/SIGN, NICE and GINA guidelines endorse the use of MART, so if this approach is preferred by the patient, an ICS/formoterol combination should be prescribed.

REFERENCES

1. BTS/SIGN. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma; 2019 https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

2. GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention; 2020 https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/

3. Newton R, Giembycz MA. Understanding how long-acting β2 -adrenoceptor agonists enhance the clinical efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids in asthma – an update. Br J Pharmacol 2016;173(24), 3405–3430. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13628

4. NICE. NICE encourages use of greener asthma inhalers; 2019 https://www.nice.org.uk/news/article/nice-encourages-use-of-greener-asthma-inhalers

5. NICE. Inhaler decision aid: Inhalers for asthma; 2019 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80/resources/inhalers-for-asthma-patient-decision-aid-pdf-6727144573

6. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2013.

Related articles

View all Articles