Improving asthma management in primary school children

Dave Edwards

Dave Edwards

BPharm PGCE DipEd SP IP

Respiratory Pharmacist,

South Pembrokeshire Cluster,

Hywel Dda University Health Board

As schools go back this month, now is a good time to check whether your children with asthma have had a recent review and they – and their teachers – are prepared to cope with their condition during the new term

Approximately, 1.1 million children in the UK are having treatment for asthma.1 Two thirds of school aged pupils with asthma will have an asthma attack in school.1 In the UK almost 70 children are admitted to hospital due to asthma every day,1 and in a single year (2012) there were 21 asthma-related deaths in children under the age of 14.2

The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) report, Why asthma still kills, highlighted that in children, poor perception of risk of adverse outcome was found to be an important avoidable factor in 70% of the deaths that were looked at, as well as poor prescribing practice, lack of a structured asthma review with a specialist and a lack of a personal asthma action plan.3

Among the report recommendations were:

- A more structured review

- very patient to have a personal asthma action plan

- Training to be given on inhaler technique, and

- Education for parents, children and those who care for or teach them, about managing asthma, emphasising the ‘how’, ‘why’ and ‘when’ they should use their asthma medications, recognising when asthma is not controlled and knowing when and how to seek emergency advice.

These recommendations form the basis of the objective for the project.

The recent NACAP Children and young people asthma clinical and organisational audits 2019/204 supports this view.

Neyland Community School in South Pembrokeshire has just under 300 primary school-aged pupils on its roll. Statistics show us that around 11% of the pupils will have asthma.1 Educating these pupils, their parents and the staff that teach and care for them about all aspects of asthma is likely to better equip them to manage their condition in both the short and longer term, leading to improved health outcomes, a reduction in emergency GP appointments for acute exacerbations, reduction in emergency admission and overnight hospital stays and a reduced risk of premature death.3

The aims of this project were to:

- To confirm diagnosis of asthma or other cause for wheeze.

- To educate and empower the pupils, their parents and teachers about asthma to enable them to self-manage their condition.

- Conduct the reviews in a child-friendly environment to encourage full participation from the patient.

This project evolved out of some work backed by Hywel Dda University Health Board’s Pacesetter funding which involved sessions talking about asthma with the staff of the local primary schools.

The asthma review project was approved pre-COVID in March 2020. The pandemic and lockdowns have limited the face-to-face contact of all concerned. We ran the project on a small scale as a test of the concept and the technology.

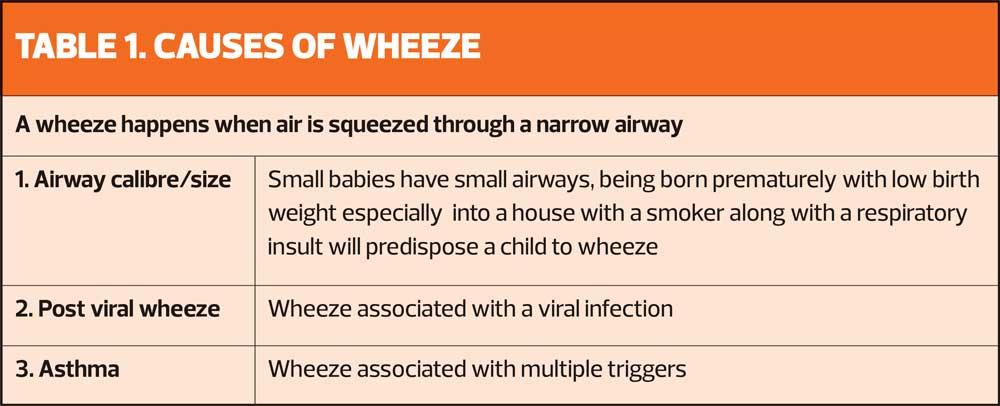

We held group sessions with the staff and the parents of all pupils who had a reliever inhaler in the school, focusing on whether the diagnosis of asthma was correct – not everyone who wheezes has asthma (Table 1) – and explaining the pathophysiology of asthma.

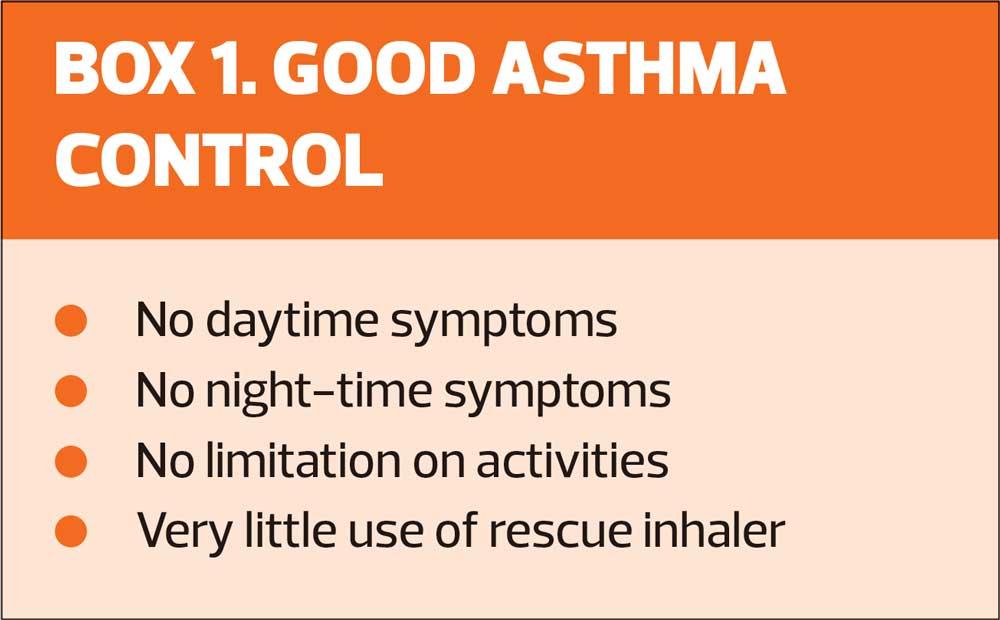

The sessions also covered the definition of good asthma control (Box 1), the action and use of medications, the important of adherence to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and inhaler technique.

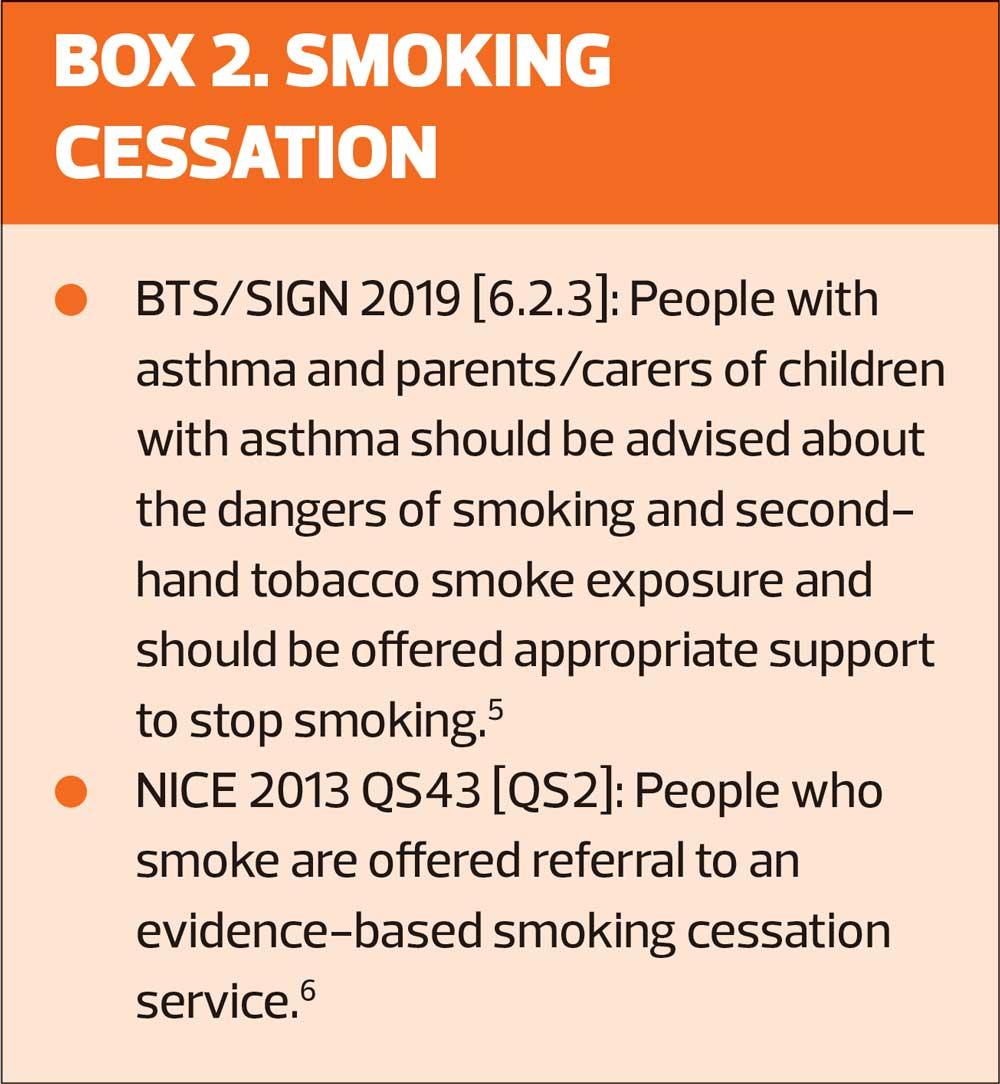

Importantly, we discussed how to recognise and safely manage worsening symptoms with personal asthma and pre-school wheeze management plans, and emphasised the importance of smoking cessation for relatives (Box 2).

We also reviewed pupils in the school, with the aim of achieving:

- Diagnostic certainty

- Treatment optimisation

- Education, education, education about

– Asthma

– Medication

– Inhaler technique

– Self-management.

MEASURABLE OUTCOMES

- Improvement in Childhood Asthma Control Test (CACT) Score which would indicate improved quality of life

- Improvement in inhaler technique

- Improvement in adherence to ICS

- Reduction in SABA usage – less use of rescue medication would indicate better control of asthma, the ultimate aim being no use of rescue medication

- Reduction in school days lost

- Reduction in exacerbations needing GP appointment, rescue steroids and/or antibiotics

- Reduction in A&E attendance/hospital admissions

Some of these outcomes could be measured at the follow up consultation, but some may take months or years to materialise.

WHAT WE DID

The first contact was with the school staff. I held a session where I discussed causes of a wheeze in children (Table 1) then concentrated on asthma pathophysiology, the action and use of medication, good control, good inhaler technique and how to recognise worsening symptoms of asthma.

The next session was with the parents of some of the children who had a blue reliever inhaler left with reception in the school. Social distancing regulations meant that this was limited to ten parents. The subject matter was much the same as the staff meeting.

It’s worth noting that the school had identified and invited the parents of some of the higher users of reliever inhaler but not all attended.

I invited all the pupils whose parents had attended to a face-to-face review in the school. When I see 6-year-olds in the surgery they look and act like very small children. I end up talking to their parents about them not to them. I was hoping by holding the reviews ‘on their turf’, in an environment that they were familiar with and felt comfortable in that we would have a more equal conversation about their condition. My feeling is that if they felt more involved in the consultation, they would have more understanding and ownership of their condition which should lead to better management.

The school allowed me to use the Community Room which had a little sofa and armchairs in. It was more like ‘The One Show’ set up than a medical consultation.

I had read/write access to the surgery’s Patient Medical Record (PMR), which meant I could look through their history, record the consultation and print prescriptions remotely.

For patients with diagnostic uncertainty, confirming a diagnosis was a priority. I did this following the British Thoracic Society/ Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN) diagnostic pathway and reviewed them in a month to look at the evidence.

For those with an asthma diagnosis or who had a high probability of asthma, I conducted the review I would have done in the surgery. Since I had already had a group consultation with the parents, I could concentrate on the child patient. After explaining who I was and what I was doing I went through the Childhood Asthma Control Test (CACT) with the patient and the parent. We talked about their symptoms, and I explained the cause of the tightness, cough and wheeze with the aid of some airways models designed by Asthma Right Care. Using the models, I explained how the medicines in the inhalers worked and then looked at their inhaler technique, correcting where necessary. I adjusted their treatment according to their symptoms (taking into account adherence and inhaler technique) following the BTS/SIGN guidelines.5 In every case I issued two new spacer devices with a mouthpiece (one for the school) and an asthma & pre-school wheeze management plan. I gave a copy of this plan to the school. I gave every patient details of the NHSWales Asthma Hub app, which contains information about asthma, inhaler technique and an electronic asthma and pre-school wheeze management plan.

At every consultation, I examined the patient and listened to their chest.

I booked a follow up appointment for four to six weeks.

FINDINGS

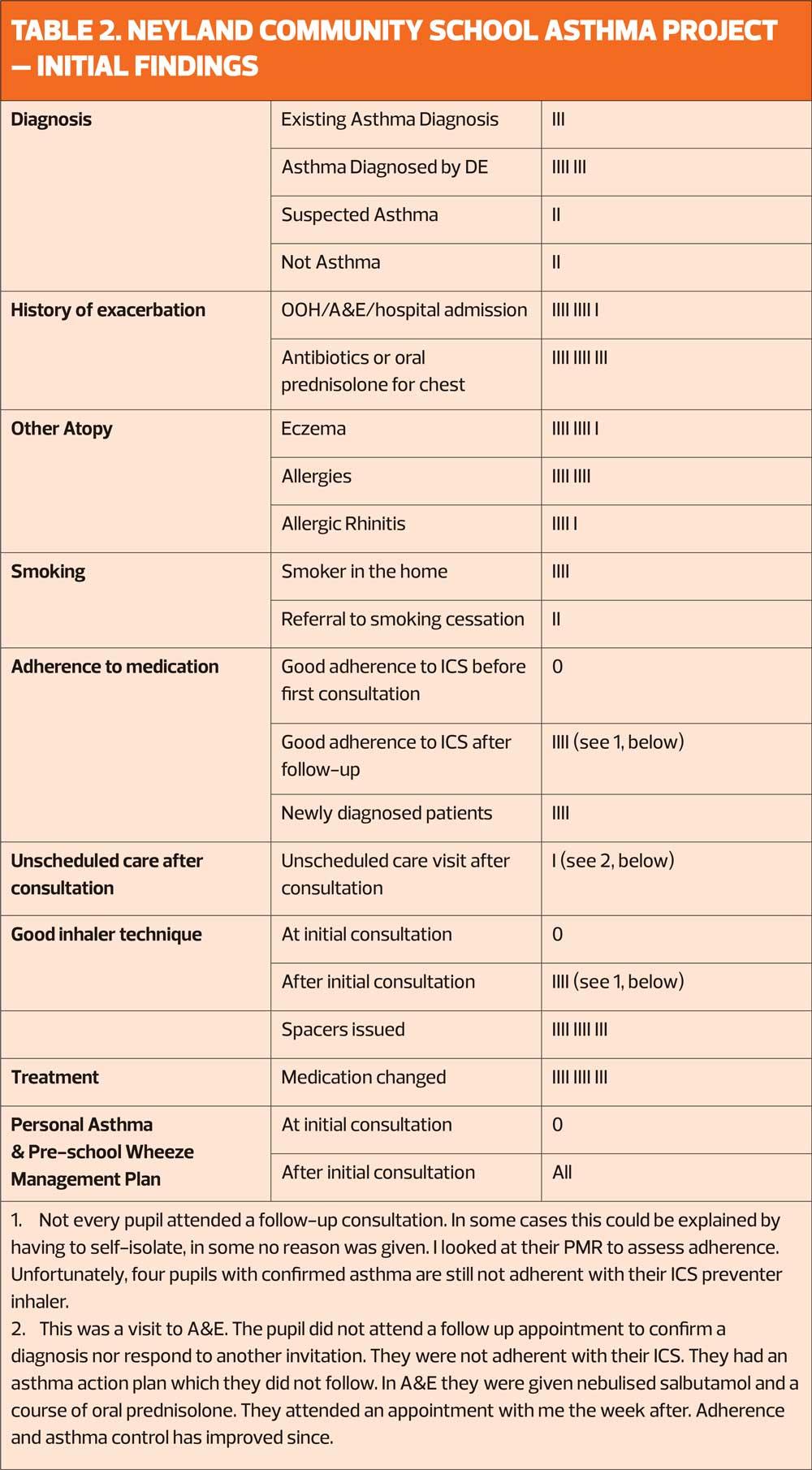

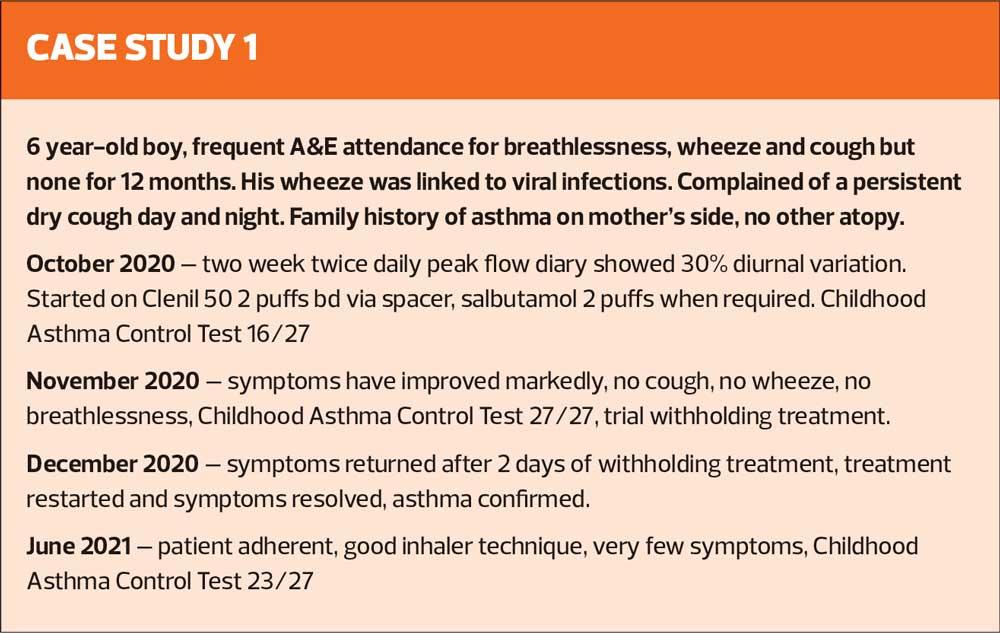

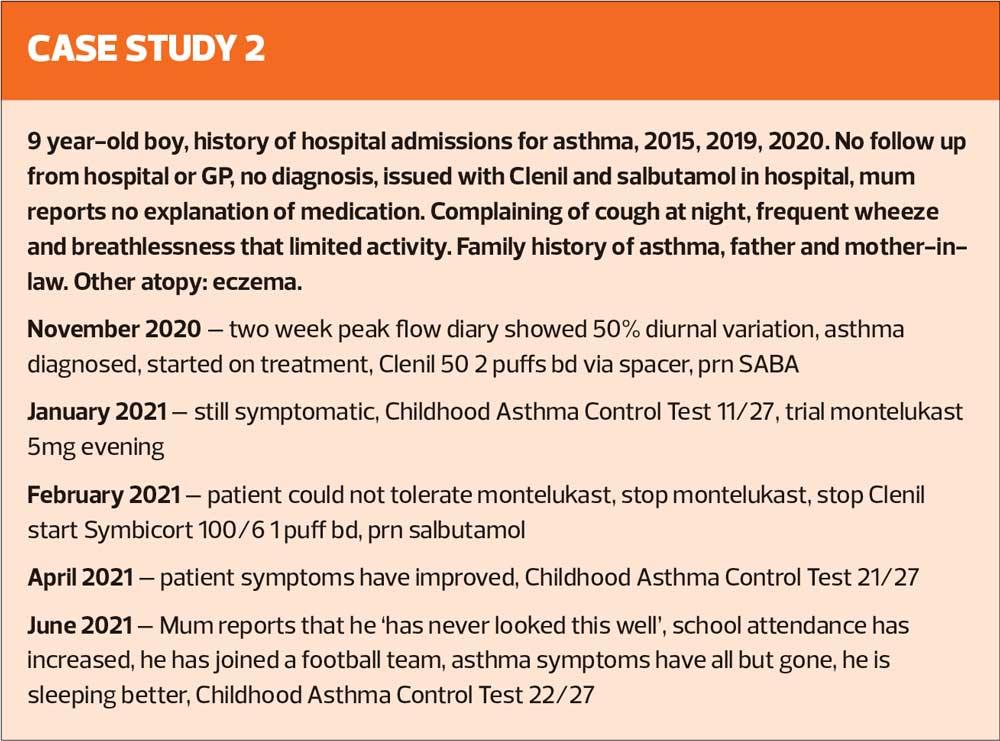

Initial results from the initiative are shown in Table 2. My first cohort was ten pupils, and I have had an initial consultation with my second cohort. The plan was to have ten in this group as well, but because some parents and pupils had to self-isolate this has been reduced to six pupils.

I found most pupils and parents were unclear about their diagnosis and their understanding of the pathophysiology of asthma and the action and use of asthma medication was poor.

Adherence to preventer medication and inhaler technique was poor.

None had an asthma action plan.

Repeated A&E attendance without follow up was common.

An asthma review in a school allows the child to play a bigger part in the review.

With appropriate treatment and education, pupils’ asthma management improves.

Following the consultation there were:

- Fewer unscheduled care visits (only one and this was a child who did not attend a follow up consultation and was not adherent with his preventer medication)

- Improved school attendance

- Increased sports participation

- Increased quality of life (using CACT)

Non-attendance at asthma reviews is a problem no matter what age of patient or the setting.

The head teacher, Clare Hewitt, commented: ‘This project has been invaluable and made a significant difference to our families and to the school. This has been seen in a number of ways but particularly, the knowledge and understanding of the condition and how best to support it has been eye opening. We have clear health plans, which enable us at school to support the children carefully and accurately. We have seen a number of other benefits, such as improved attendance, access to PE and extra curriculum activities and improved confidence. We have had some children that have been diagnosed, medication reviewed, and also some children removed from the asthma list completely. The constant support and regular reviews have ensured that all our children are appropriately supported, and this increased knowledge has helped both our families and the school.

‘This project has helped us all, including delivering whole staff training and also parent workshops. The pupils, parents/ carers and staff have benefited greatly and hope to continue with this invaluable work.’

Conclusion

An asthma review in a school setting is an effective and efficient way of equipping the patient, parent and school staff with the knowledge and skills necessary to safely manage their asthma at an early age.

Confirming the diagnosis of asthma allows this education to be tailored to the individual.

Being an expert patient leads to better control. Simple things like explaining the patient’s symptoms and how and when to use the inhalers can lead to improvements in adherence and less asthma symptoms.

Aiming for good control of asthma means that the child’s physical development, participation in sports and school attendance should not be affected by the condition.

Having a written or electronic asthma action plan that gives clearly defined steps in response to worsening symptoms is effective in keeping patients away from the unscheduled care environment.

Treating other atopy, especially allergic rhinitis, leads to an improvement in asthma control.

Discussing smoking status with the parents of children with asthma and offering support should they choose to quit is an effective method of engaging smokers in a quit attempt.

Nothing I have done is complicated. I do not change my explanation of asthma pathophysiology or the action and use of inhalers whether I am explaining it to a 6-year-old or a headteacher.

REFERENCES

1. Asthma UK. https://www.asthma.org.uk/about/media/facts-and-statistics/

2. British Lung Foundation. https://statistics.blf.org.uk/asthma

3. Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills: the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) Confidential Enquiry report. London: RCP, 2014

4. Sinha I, Latchem S, Amusan L, et al. National Asthma and COPD Audit Programme: Children and young people asthma clinical and organisational audit 2019/20. Combined clinical and organisational audit of children and young people asthma services in England, Scotland and Wales. London: RCP, 2021

5. British Thoracic Society (BTS)/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). SIGN

158: British guideline on the management of asthma – A national clinical guideline. [Revised edition published July 2019]. https://www.britthoracic.org.uk/qualityimprovement/guidelines/asthma

6. NICE QS43. Smoking: supporting people to stop.

Related articles

View all Articles