Improving asthma care for children and young people

Viv Marsh

Viv Marsh

RGN, RSCN, SCPHN, BSc (hons), QN

Specialist Practice,

Independent Prescriber

Clinical Lead for CYP Asthma Transformation, Black Country ICB Transformation and Facilitation

Co-ordinator for the IMP²ART research programme, University of Edinburgh. Lead Asthma Tutor, Rotherham Respiratory

Practice Nurse 2023;53(6):15-20

Practice Nurse explores the factors contributing to poor outcomes in children and young people with asthma, how the NHS is tackling the problem, and the vital role of nurses in general practice (GPNs) in delivering the highest standards of asthma care to these young patients

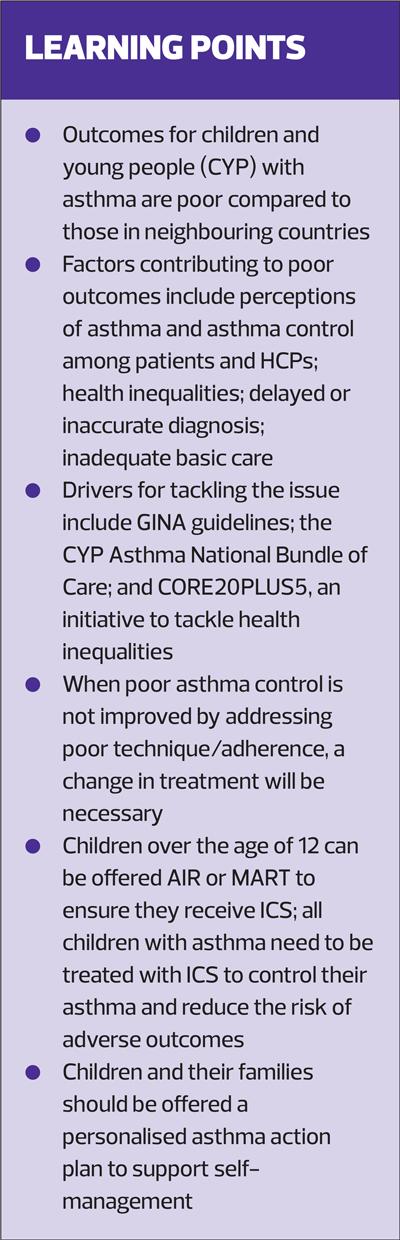

Outcomes for children and young people (CYP) with asthma in the UK are shockingly poor in comparison to our neighbouring countries.1 Hospital admission and mortality rates in adolescents are the highest in Europe, and CYP in the UK experience a significant burden of morbidity including school absence, sleep disturbance and avoidance of physical or social activities.1 Given that more than 1 million children in the UK are treated for asthma,2 the current state of affairs really is a problem.

FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO POOR ASTHMA OUTCOMES

1. Perceptions of asthma

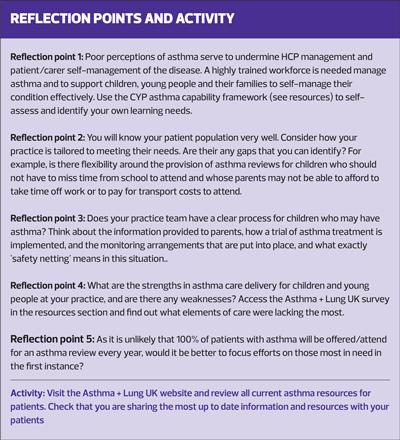

Asthma is a common respiratory condition in all age groups, particularly in children, and studies have shown that perceptions of the disease among both patients and healthcare professionals are poor.3

The report from the National Review of Asthma Deaths4 coined the term ‘complacency’ around asthma and called for action to improve basic care and increase awareness that asthma can and does kill. The REALISE study is just one of many that show wide discrepancies between patients’ perceived and actual level of asthma control.5 Furthermore, specific paediatric studies also highlight discrepancies between the perceptions of children, their parents and healthcare professionals about asthma control, and the vital role of nurses in general practice in providing education to children with asthma and their parents.6

See Reflection point 1.

2. Health Inequalities

Poor asthma outcomes are strongly linked to health inequalities with most admissions to hospital occurring in children from our most deprived communities and from ethnic minority backgrounds.7 (Reflection point 2).

3. Delays or inaccurate diagnosis

Diagnosis of asthma in any age group is challenging but in children it is particularly difficult, in part because young children cannot always perform objective tests such as spirometry. However, asthma is a clinical diagnosis and the structured process outlined in all national and international guidelines specifies that treatment should not be delayed in children with suspected asthma (Reflection point 3). All children with suspected asthma should be started on an 8-week trial of treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), and safety netting advice provided to their parents.

4. Inadequate basic care

The Asthma + Lung UK annual survey8 in 2022 found that only 30% of people with asthma had received basic [essential] care in the previous year with most respondents not having had their inhaler technique checked or an asthma action plan discussed and updated (Reflection point 4).

DRIVERS FOR TACKLING THE PROBLEM

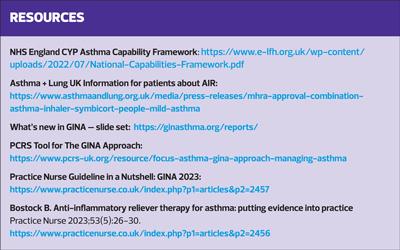

Delivery of evidence and guideline-based care is the primary vehicle for effective asthma management, but guidelines have been around for a long time and, given the poor outcomes highlighted above, their impact must be questioned. The teams behind the well-recognised British Asthma Guidelines9 and more recent NICE guidelines10 are currently working together to produce a single UK guideline for the management of asthma; publication is expected in October 2024.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA)11 offers a strategy guiding asthma management across the globe and its approach is gathering significant traction in the UK at the moment. This may, in part, be due to:

- A dynamic strategy, with annual updates bringing latest evidence to clinical practice very quickly

- Early adoption of new treatment approaches such as Anti-Inflammatory Reliever therapy (AIR)

The CYP Asthma National Bundle of Care,7 published in 2021, contains a number of deliverables across five domains that each Integrated Care System (ICS) is expected to meet to drive the change that is needed to improve outcomes and patient experience. Underpinning the bundle of care is a ‘capability framework’ for all professionals who work with children (including teachers and social care staff).

CORE20PLUS5 is an NHS England initiative to tackle health inequalities aiming to focus attention for health care service provision and delivery to the people living in the most deprived areas (CORE20) in the country and those in defined groups such as people from ethnic minority backgrounds, with learning disabilities or where access to healthcare is poor (PLUS).12 Five clinical target areas are included and in the CYP CORE20PLUS5, asthma is the first clinical area with targets set to reduce asthma attacks and overreliance on reliever inhalers.

THE GPN ROLE IN CYP ASTHMA

GPNs are particularly well placed to support effective asthma management for children and young people. Asthma care for all age groups must be provided by healthcare professionals (HCPs) who are appropriately trained and up to date with current evidence and guidelines, but in a pressurised system it can be a challenge to develop and maintain knowledge and skills. A further consideration is that generalist HCPs may feel less confident with managing asthma in children than they do with adults.13 GPNs are at the forefront of asthma management, they are among the professional groups most trusted by the public,14 and their role in the delivery of high-quality essential asthma care is vital.

Basic [essential] asthma care

The aims of asthma care are to achieve and maintain asthma control, avoid asthma attacks and to enable people to live well with their asthma. Guidelines recommend a full review with an HCP trained in asthma at least annually, and reviews should include:

- Assessment of current asthma control

- Assessment of future asthma risk

- Assessment of adherence and inhaler technique

- Medicines optimisation

- Supported self-management

Asthma control must be assessed using a validated tool such as the Asthma Control Test (ACT) or children’s Asthma Control Test (c-ACT). Whilst these are tools self-administered by patients, it is important that results are discussed and not simply taken at face value. Patients may under or overestimate their asthma control and researchers have found that such estimations can be influenced by educational level and patients’ personal beliefs.15 Understanding why ACT/c-ACT scores are low is a vital part of the assessment as this information will guide the actions needed.

A comprehensive systematic review identified that children at greatest risk of future asthma attacks were those with a history of previous asthma attacks and persistent asthma symptoms, particularly if they had poor access to health care.16 Children living in poverty, from some ethnic minority backgrounds, with co-morbid allergic/atopic disease and on sub-optimal therapy were found to be at moderately increased risk.

Understanding such risk factors should help HCPs to tailor asthma care and interventions to their patients. For example, children at high risk of future asthma attacks can be monitored closely, offered personalised support for self-management, and referred to specialist care. The SABINA Junior study found that the risk of asthma attacks increased in children using 3 or more canisters of short acting beta agonist per year.17 This study also found that most asthma attacks in children and adolescents are managed in primary care and that >30% of patients were not prescribed inhaled corticosteroids (ICS). The authors concluded that monitoring of symptom control and SABA use should be adopted in clinical practice to enable early identification of deteriorating asthma control.

Proactive approaches to reducing risk of future asthma attacks include:

- Identifying those most at risk by interrogating routine practice held data and prioritising them for review

- Following up all patients after an asthma attack

(See Reflection point 5).

Poor adherence with, or suboptimal provision of, asthma treatment (ICS) remain the most common factors in poor asthma control in children; it is a major factor in asthma attacks and has also been linked to asthma deaths.18 There is no easy or foolproof way of detecting poor adherence but methods include monitoring prescription issues, careful use of open questions and, more recently, use of electronic devices such as smart inhalers. Effective communication, trust and collaboration between HCP and child or family are crucial for the development of therapeutic relationships, which enhance supported self-management.

A published review of adherence in adolescents with asthma highlights collaboration and shared decision making as one possible solution for poor adherence in this age group,19 with the use of motivational interviewing techniques and goal setting strategies to improve medication adherence. The review also suggests inhaler choice/technique and alternative medication regimes such as once daily treatment or Maintenance and Reliever Therapy (MART) as other possible solutions.19

Telephone reviews have played a part in routine asthma management for many years and have been shown to improve patient access;20 however, a wholescale shift towards remote delivery of asthma care occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although necessary at the time, the fact that it is not possible to check inhaler technique fully during a telephone consultation is a major barrier to effective asthma care. As restoration of health services following the pandemic continues there are now strong calls for the return to face-to-face asthma reviews. Indeed, the current Quality Outcomes Framework specifies that a full face-to-face (or video) assessment of inhaler technique must be included in routine asthma care.21 There will always be a place for various forms of remote care delivery along points of the asthma management pathway but, unless using video technology, the requirement, at least annually, for assessment of inhaler technique can only take place during an in-person consultation with an appropriately trained HCP.

Effective inhaler technique is vital for patient safety because without it, patients are at risk of poor asthma control and asthma attacks.22 While prescribers are responsible for ensuring that patients can use their inhaler devices,23 it is GPNs who are most involved in this element of respiratory care. However, nurses must be mindful of the fact that knowledge of correct inhaler technique is poor among HCPs as well as patients,22 therefore competence in both assessing and teaching inhaler technique is the most fundamental step in essential asthma care.7

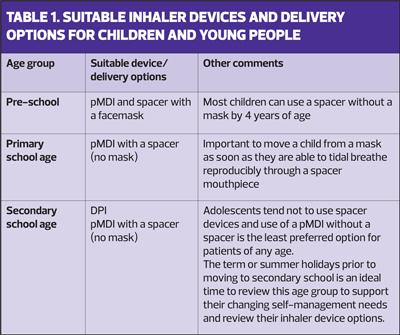

Appropriateness of the inhaler or spacer device for each child’s age and ability, along with their preference, must be considered when discussing treatment options or making any changes to existing management.23 See Table 1.

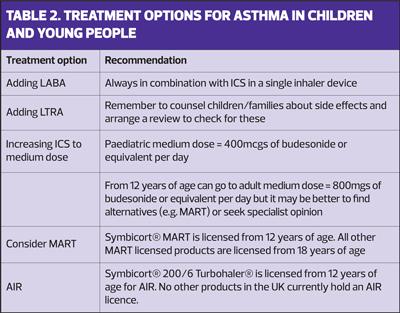

Inhaler technique and inhaler devices are core elements of medicines optimisation in all respiratory patients, and guidelines recommend that these are dealt with before adding or increasing treatment. ICS are the first line treatment recommended by all guidelines for the management of asthma.9–11 In cases of poor asthma control not improved by addressing poor inhaler technique and/or poor adherence, a change in asthma treatment will be necessary. Options include:

- Adding a long-acting beta agonist (LABA) to low dose ICS

- Adding a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) to low dose ICS

- Increasing the ICS to medium dose

vConsidering MART in adolescents

Referral for specialist opinion should be considered for any patient with persistent poor asthma control or requiring 2 or more courses of oral steroids for acute asthma in 12 months.9–11

GINA RECOMMENDATIONS FOR MANAGING ASTHMA

A combination inhaler made up of ICS/formoterol is GINA’s preferred reliever option. GINA makes a strong case for the use of an Anti-Inflammatory Reliever (AIR) combination inhaler in place of a standard reliever (short acting beta agonist[SABA]) inhaler in adolescents and adults. This can be achieved by treating patients with an inhaler containing both ICS and formoterol (fast-acting LABA), but how does this differ from MART?

They are similar, but in a MART regime the patient will take their ICS/formoterol inhaler once or twice daily for maintenance plus additional doses for relief of symptoms when needed, whereas in an AIR only regime the patient will only use their ICS/formoterol inhaler for relief of symptoms when needed and they will not have any regular maintenance treatment.

The rationale for these approaches is that patients will be getting more ICS when they are symptomatic in MART, and they will be getting some ICS when they are symptomatic in AIR only.

Patients on MART or AIR should not be prescribed any other reliever inhalers.

AIR only is licensed in the UK and is appropriate for use in patients from 12 years of age with infrequent, intermittent symptoms who have mild asthma.

Evidence for AIR and MART is lacking in children under 12 years of age, but UK-based and international studies are underway. If proven safe and effective in this age group, wide scale paradigm shifts in asthma management across the life course of the disease, leading to an end to the dangerous over reliance on SABA in asthma is, in the author’s opinion, likely to occur.

For patients who only use a SABA inhaler for symptom relief, the GINA strategy offers an alternative option to AIR by recommending that a dose of ICS is taken every time the reliever is used. This recommendation applies to children from 6 years of age (preferred option) as well as adolescents and adults (alternative to AIR option).

All guidelines recommend strategies to support patients to self-manage their asthma. At its most basic level this requires HCPs to support CYP and their families to understand their asthma and their treatment plan, and to be able to recognise and take action when their asthma control is deteriorating or they are having an asthma attack.9–11 There is strong evidence that supported self-management is effective – but support must be tailored or personalised to each patient’s needs.24 When planning or offering self-management support, considerations for nurses include the level of capability, opportunity and motivation that the child or their family has for self-care. Patient/parent preference is key and shared decision making is paramount; for example, provision of a personalised asthma action plan is a core component of an asthma review but the patient must be involved in the decisions around what to include in the plan and their preferences should guide the type and format of the plan.

High quality resources are available from Asthma + Lung UK to support CYP with asthma and their families, and include advice, information, an online forum, a specialist nurse helpline and of course, a range of inhaler technique videos and asthma action plans, including a new MART plan (See Activity).

CONCLUSION

Asthma outcomes for children and young people in the UK are poor and this article has considered some factors that may be implicated. There are a number of challenges to high quality asthma care in the NHS at the moment and it is clear that improvement is needed. The NHS England transformation programme includes a bundle targeting asthma care in CYP, providing an opportunity and platform for change. New approaches such as the current GINA strategy are potential game changers, but the need for high quality basic [essential] care is as fundamental as ever and it is GPNs who are pivotal in its delivery.

REFERENCES

1. RCPCH State of Child Health; 2021. https://stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk/evidence/long-term-conditions/asthma/

2. Asthma + Lung UK. Statistics about lung disease in the UK (visuals); 2023 https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/asthmaandlunguk/vizzes

3. Menzies-Gow A, Chiu G. Perceptions of asthma control in the United Kingdom: A cross-sectional study comparing patient and healthcare professionals’ perceptions of asthma control with validated ACT scores. npj Prim Care Respir Med 2017;27(1).

4. Levy ML. National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD). Brit J Gen Pract 2014;64(628).

5. Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: The recognise asthma and link to symptoms and experience (REALISE) survey. npj Prim Care Respir Med 2014;24(1).

6. Searle A, Jago R, Henderson J, Turner KM. Children’s, parents’ and health professionals’ views on the management of childhood asthma: A qualitative study. npj Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1).

7. NHS England. The National Bundle of Care for Children and Young People with Asthma; 2022 https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/national-bundle-of-care-for-children-and-young-people-with-asthma/

8. Asthma + Lung UK. Fighting Back, Basic Care Survey; 2022 https://www.asthmaandlung.org.uk/sites/default/files/Fighting%20back_V3.pdf

9. British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network. British guideline on the management of asthma 2019. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

10. NICE NG80. Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management; 2017: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80

11. GINA. Global Initiative for asthma; Main Report 2023; 2023 https://ginasthma.org/2023-gina-main-report/

12. NHS England. Children & Young People CORE20PLUS5 https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/core20plus5/core20plus5-cyp/

13. Elliott J, Watson M, Goldring S. Abstract 253 Evaluating paediatric asthma MDTs across London. British Paediatric Respiratory Society). Arch Dis Child 2022;107 (Suppl 2) doi:10.1136/archdischild-2022-rcpch.378

14. IPSOS. Ipsos veracity index. https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/ipsos-veracity-index-2022

15. Crimi C, Campisi R, Noto A, et al. Comparability of asthma control test scores between self and physician-administered test. Respir Med 2020;170:106015

16. Buelo A, McLean S, Julious S, et al. At-risk children with asthma (ARC): A systematic review. Thorax 2018;73(9):813–24

17. Morgan A, Maslova E, Kallis C, et al. Short-acting β2-agonists and exacerbations in children with asthma in England: Sabina junior. ERJ Open Research. 2023;9(2):00571–2022

18. Pearce CJ, Fleming L. Adherence to medication in children and adolescents with asthma: Methods for monitoring and Intervention. Exp Rev Clin Immunol 2018;14(12):1055–63.

19. Kaplan A, Price D. Treatment adherence in adolescents with asthma. J Asthma Allergy 2020;Volume 13:39–49

20. Pinnock H, McKenzie L, Price D, Sheikh A. Cost-effectiveness of telephone or surgery asthma reviews: economic analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2005 Feb;55(511):119-24.

21. NHS England. Quality and Outcomes Framework guidance for 2023/2024 https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/quality-and-outcomes-framework-guidance-for-2023-24/

22. Plaza V, Giner J, Rodrigo G, et al. Errors in the Use of Inhalers by Health Care Professionals: A Systematic Review. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018;6(3):987-995

23. UK Inhaler Group. Inhaler standards and competency document. https://www.ukinhalergroup.co.uk/

24. Morrow S, Daines L, Wiener-Ogilvie S, et al. 2017 Exploring the perspectives of clinical professionals and support staff on implementing supported self-management for asthma in UK general practice: an IMP2ART qualitative study. npj Prim Care Resp Med 2017;27:45.

Related articles

View all Articles