Asthma in children and young people: an update

Viv Marsh

Viv Marsh

RGN, RSCN, SCPHN, BSc (hons)

Specialist Practice, Independent Prescriber

Facilitation Co-ordinator for the IMP²ART research programme and Independent Paediatric Asthma Nurse

Practice Nurse 2021;51(9):15-20

Asthma is a complex condition that is difficult to diagnose, particularly in children. Reflecting on both old and new challenges, this article focusses on the diagnosis and management of asthma in children underpinned by current evidence, guidelines and standards for professional practice

Misdiagnosis of asthma in children is common, with one primary care study finding >50% of children with asthma were misdiagnosed.¹ Despite the availability of effective treatments and a range of evidence-based guidelines to underpin high quality care, asthma places a significant burden on the lives of children and young people in the UK. Data suggest that more than 1 million children in the UK are currently receiving asthma treatment; equating to 1 in 11 children considered to have the condition.²

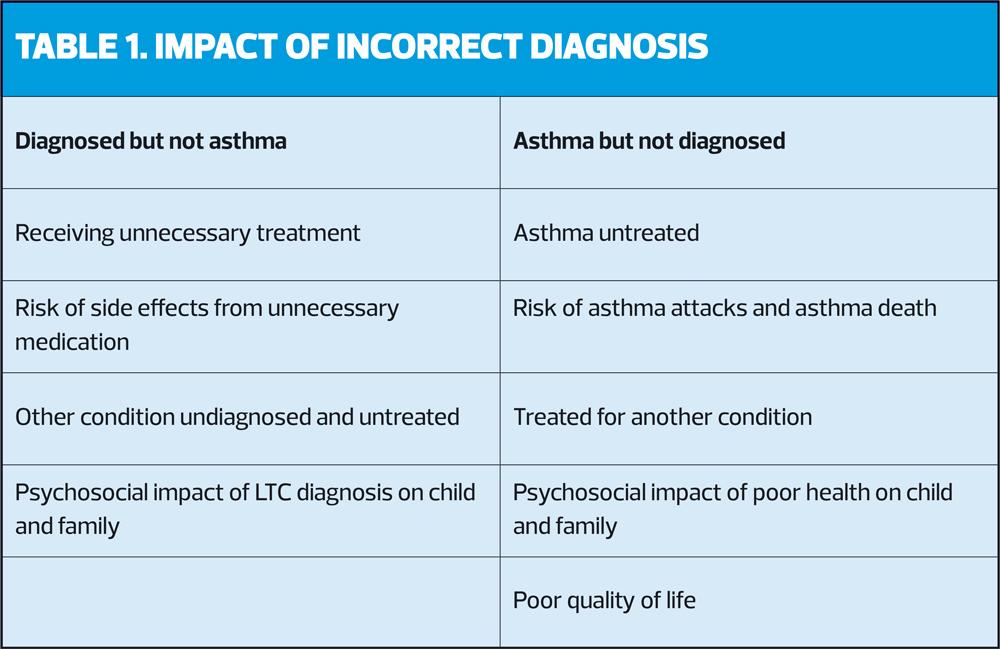

Getting the diagnosis right is always the goal but is not easy to achieve. Let’s start with thinking about the impact of an incorrect diagnosis (Table 1).

The implications of misdiagnosis for patients are clear but we also need to consider the professional and medico-legal implications for health professionals. Currently, malpractice claims relating to respiratory conditions in children are uncommon in the UK, but who knows what the future holds. One study of malpractice claims in France reported a 66% fatality rate in cases relating to misdiagnosis of asthma in children.3,4

Professionally, nurses are required to:5

- Prioritise people

- Practise effectively

- Preserve safety

- Promote professionalism and trust

Our professional standards are a useful tool to support our reflection and actions in relation to asthma diagnosis in children. We know asthma is difficult to diagnose, we know it is commonly misdiagnosed, and General Practice Nurses, who deliver the vast majority of asthma care in the UK, often find themselves in the ‘hot-seat’ with parents. Anxious parents may press for a label [diagnosis] or may feel angry if their child was diagnosed in error; both scenarios are commonplace in the author’s experience. The solution to the problem is to confirm the diagnosis with objective evidence and avoid labelling the child until this can take place. This involves working in partnership with parents as well as our clinical colleagues in primary and secondary care over a period of time.

Using the right language/terminology is a helpful part of this process: ’wheezing is very common in children and not all children who wheeze have asthma’; ‘we can’t be completely sure it is asthma until your child is able to perform these tests’; ‘it might be asthma but until we can be absolutely sure we will call it suspected asthma’.

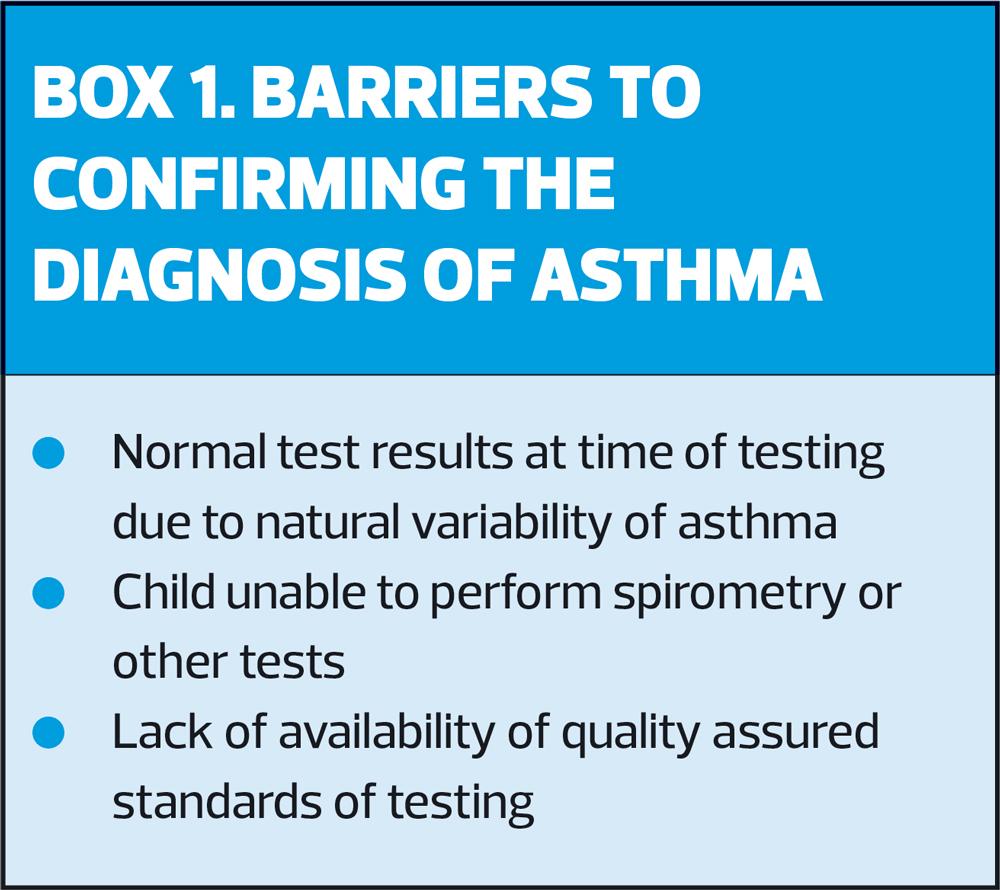

Current NICE guidelines6 and QoF rules7 require the diagnosis of asthma to be confirmed with two abnormal test results, and state that diagnosis must not be made based on symptoms alone. Clearly this is challenging for a whole host of reasons (Box 1), however the case for getting the diagnosis right is irrefutable.

These challenges are not new and it is reassuring to know that they are being addressed by the NHSE Children and Young People’s Asthma Transformation Team, working within the Respiratory Programme of the NHS Long Term Plan.8 Diagnostic hubs are likely to be the way forward but they will not entirely remove the role that GPNs have in the diagnosis of asthma in this or any other age group.

THE DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

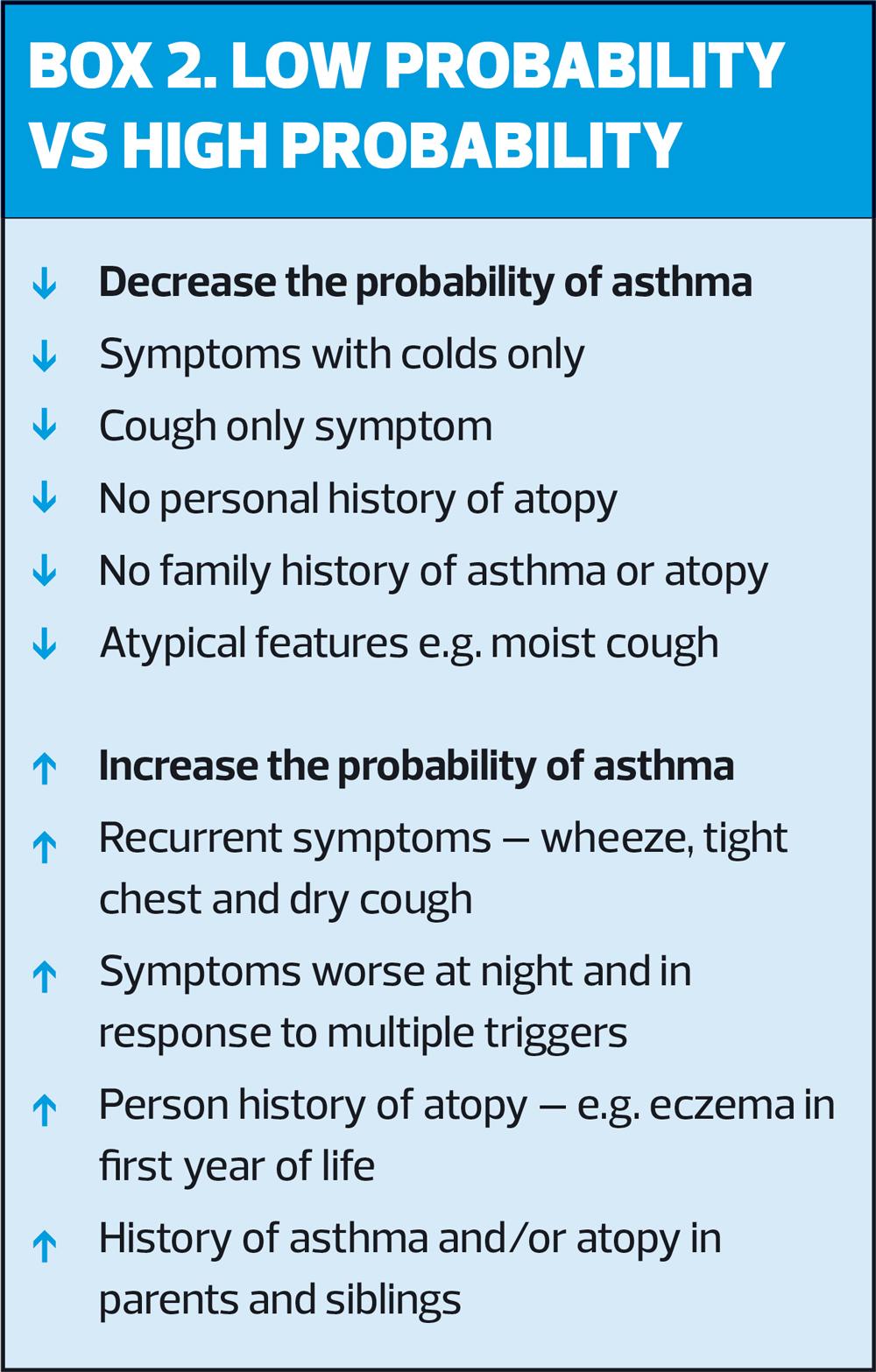

Beginning with careful history taking and clinical examination, a structured process underpins the diagnosis of asthma. Using the history to establish ‘probability’ is helpful (Box 2);9 remember that asthma is primarily a disease of wheezing in children but not all wheeze is asthma. Documented evidence of wheeze, heard by an appropriately trained health professional on auscultation, is a key clinical indicator. This and other symptoms have multiple triggers in children with asthma including viral infections, irritants such as cigarette smoke and pollution, and allergens. Asthma in children is usually related to allergy, therefore signs of atopy or history of allergy are the next features to look for.

Clinical examination is essential to identify any abnormality that may be consistent with asthma or an alternative diagnosis. Visual observation of the chest is useful in children therefore removal of clothing from the upper body is important.

- An abnormal chest shape might indicate chronic air trapping or hyperinflation; often evident in children who have had uncontrolled respiratory symptoms for some time.

- Auscultation of the chest may reveal wheeze; absence of wheeze does not rule out asthma.

- Examination of the child’s fingers and nails for signs finger clubbing which would indicate cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis and require immediate specialist referral.

- Observation of the skin for dryness or excoriation, which could suggest eczema and increase the probability of asthma.

- Observation of the child’s face for signs of allergy such as a nasal crease or allergic shiners.

If, based upon the structured clinical assessment, asthma is suspected, objective testing should be carried out where possible to assist in confirming the diagnosis. Until the diagnosis can be confirmed the medical record code or label to use is ‘suspected asthma’.

OBJECTIVE TESTS

Spirometry followed by reversibility testing are the initial recommended tests for asthma diagnosis; abnormal spirometry in children is identified using the Lower Limit of Normal (LLN) in children rather than arbitrary ratios; all modern spirometers calculate LLN automatically. A 12% improvement in FEV1 post bronchodilator is considered a positive reversibility test. Spirometry can be performed by most children from 6 years of age, however access to health professionals trained and accredited to perform and interpret Quality Assured Diagnostic Spirometry in children is currently extremely limited in the UK.10 The Association for Respiratory Technology & Physiology (ARTP) paediatric spirometry certificate is currently being updated and developed to include a standalone certificate, a combined adult and paediatric certificate or as a ‘bolt-on’ to the adult certificate.11

Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide (FeNO) is the next test recommended within the diagnostic process.6 This test measures the level of nitric oxide, an inflammatory biomarker, in exhaled breath. In children, measurements ≥35ppb are abnormal and an indicator of airway inflammation.6 FeNO testing is simple to administer and for children to perform. However, despite now being available and a recommended test for some years, it is not widely available in primary care.

Peak expiratory flow rates (PEFR) can demonstrate variability which would support an asthma diagnosis, and measurements can be performed by children from about 5 or 6 years of age. However, the reliability of this method depends on a number of factors including patient technique and accurate recording of at least twice daily measurements over a 2-4 week period. Many children cannot reliably perform PEFR measurements until they are older and concordance with twice-daily measurements is often poor. For these reasons, PEFR variability is no longer a preferred test in the diagnosis of asthma in children and while still included in guidelines, caution is urged in their interpretation.6,9

Trials of treatment (with inhaled corticosteroids [ICS]) are a common strategy for managing suspected asthma in children, however their acceptability as a diagnostic tool is waning. Where asthma is suspected and symptoms respond to a 6-8 week trial of ICS, the likelihood of asthma is increased. However, extreme caution is needed as the symptoms may have resolved spontaneously, thus it is wise to stop the ICS and monitor the child for returning symptoms, which will occur at some point if the child has asthma. Any trial of treatment must now be supported with objective tests and we should remember that diagnosis must be confirmed on the basis of two abnormal tests.6.7

When initiating a trial of treatment in a child with suspected asthma remember to ensure parents are fully informed at the outset and understand that even if the response appears to be good, the next logical step will be to stop the trial to monitor for returning symptoms, and once the child is able to perform objective tests, these will be arranged.

Forced oscillometry is a lung function test emerging as a potential objective tool for asthma diagnosis. It is not an effort-dependent test and children find it easy to perform. However, there are currently no gold standard guidelines for performing or interpreting this procedure so whilst it is promising for the future, it is not currently in use in clinical practice.12

ASTHMA MANAGEMENT

Once diagnosed, the goal of management is to maintain control of the disease on the lowest possible dose of medication. ICS is the first-line treatment of choice and should be initiated in all children with asthma; very-low dose or low-dose is recommended depending on the age of the child.6,9 The range of drugs licenced for use in children is limited and Clenil* 50mcgs 2 puffs twice a day (very low dose) or Clenil 100mcgs 2 puffs twice a day (low dose) is the usual starting point. Parents may be concerned about ‘steroids’ but should be reassured that ICS is the most effective treatment for controlling asthma and that in recommended doses is very safe; guidelines suggest not exceeding 400mcgs per day (low dose) in under 12’s and 800mcgs per day (medium dose) in over-12 year olds; beyond this specialist referral is required.6,9

*Note that not all ICS products are dose equivalent and therefore must be prescribed by brand name.

Montelukast, an anti-leukotreine drug with some anti-inflammatory properties, is an option in children under 5 years of age who cannot take ICS, however ICS remains the first-line choice of regular prevention treatment. Montelukast can also be added to treatment in children already taking ICS but whose asthma is not fully controlled and this is the preferred initial add-on therapy in the NICE guidelines.6 Long-acting bronchodilator (LABA) is the initial add-on option for children over 5 years of age uncontrolled on ICS alone recommended by the BTS/SIGN British Asthma Guideline.9 The difference in guidelines is frustrating for health professionals in front line clinical practice but understanding that both options are recommended and tailoring the choice to the individual child is good practice. Local formularies and guidelines may have a part to play in this choice but the publication of joint BTS/SIGN and NICE national asthma guidelines are eagerly awaited.

LABA must always be used in conjunction with ICS, therefore the use of combination inhalers is strongly recommended as this will avoid the risk of LABA being taken as monotherapy.

Symbicort for use as both Maintenance and Reliever Therapy (MART) is licenced from 12 years of age, offering an excellent option to consider for adolescents whose asthma is persistently poorly controlled.

Children with persistent poor asthma control despite moderate dose ICS plus additional controller therapies (LABA and LTRA) must be referred for assessment by a paediatric respiratory specialist health professional.

Growth, or failure to grow as expected, is an important marker of a child’s health and wellbeing. Parents will be reassured that their child’s growth is being monitored regularly. To monitor a child’s growth accurately, height (ideally measured using a Leicester height measure) and weight must be plotted on an appropriate centile chart and compared to previous records.

INHALER TECHNIQUE

Most children with asthma use pressurised metered dose inhalers (pMDI) with a spacer; when they are older, other options such as dry powder inhalers (DPI) or breath-actuated pMDIs become available. Very young children will need a spacer with a facemask, but once they can tidal-breathe reproducibly through a mouthpiece, there is no further need for the mask; indeed a spacer without a mask is preferred as soon as possible as drug deposition in the airways will be improved. Most children can use a spacer without a mask from 3 or 4 years of age. The UK Inhaler Group recently published a set of national standards for inhaler technique,13 and these are a useful guide for the steps to follow when teaching or assessing patient’s inhaler technique.

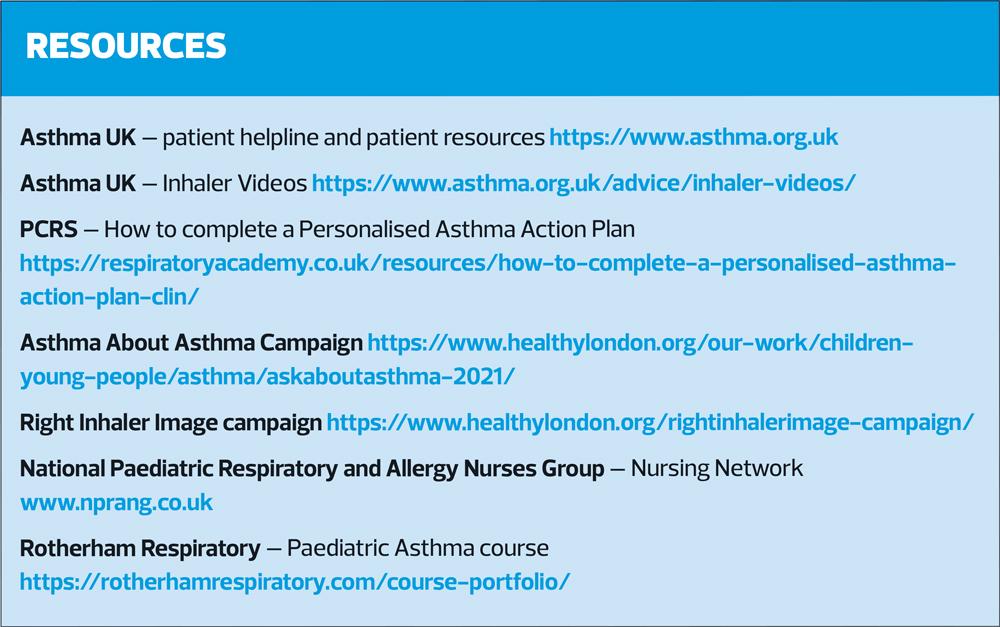

Poor inhaler technique, which is directly linked with poor asthma outcomes, is very common in patients and healthcare professionals.14 The Asthma UK inhaler videos (see resources) are an excellent source of guidance for everyone about the correct use of inhaler devices and we, as health professionals, must be sure that we are able to assess, demonstrate and teach inhaler technique to a high standard.

ASTHMA CONTROL

Comprehensive assessment of current control and future risk of asthma attacks is necessary at least annually ,but more frequently in children with sub-optimal asthma control.9 Current symptom control is best assessed by use of a validated tool such as the Asthma Control Test (ACT) from 12 years and the Childhood Asthma Control Test (C-ACT) from 3-11 years of age.15 The score provides a marker of current control and a benchmark for ongoing assessment. Questionnaires can be sent to patients/ parents electronically to complete in advance of a consultation or as a risk stratification tool.

Overuse of short acting bronchodilators (SABA) is a critical marker of asthma control; use three times a week or more is a firm indicator of poor control. Assessment must consider the fact that some children use SABA habitually, and this practice should be actively discouraged (including routinely pre-exercise).

Any asthma attack is considered a complete loss of asthma control with key opinion leaders now saying that there should be a zero tolerance of asthma attacks in children. An asthma attack is the strongest risk factor for future asthma attacks, therefore careful monitoring while control is regained and subsequently maintained is important. Any child who has required ≥2 courses of oral steroids in the previous 12 months for asthma must be referred to a paediatric respiratory specialist health professional for full assessment.6,9

Common reasons for poor asthma control are:

- Failure to take prevention treatment regularly as prescribed

- Poor inhaler technique resulting in sub-optimal doses of drug delivery to the airways

- Ongoing exposure to triggers factors including pollution

- Inadequate levels of treatment for the current disease severity

Before increasing treatment in a child with poor asthma control, carry out a full assessment to ensure they are using their existing prevention treatment correctly and regularly as prescribed.

COVID-19 AND PAEDIATRIC ASTHMA

It is reassuring to know that children with asthma are not at increased risk of COVID-19 adverse outcomes such as hospitalisation or death.16 But the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way asthma care is delivered and many changes are here to stay. Remote consultations and telephone reviews are convenient and often preferred by patients/parents; however, when poor asthma control is identified, a full assessment of inhaler technique is essential. Harnessing technology and data will enable care to be targeted to those in greatest need, perhaps with face-to-face consultations being offered to those at risk or with poor control.

Social distancing and lockdown measures resulted in a reduction in the viral load circulating in the community last year,16 but as we approach this winter, we are already seeing an increase in asthma attacks triggered by viral infections. The current surge in paediatric respiratory infections is anticipated to continue throughout the winter months with increased pressures on all health services. The Ask About Asthma Campaign (see Resources) aims to reduce the impact of the winter upsurge in asthma attacks by encouraging practices to review children with asthma, optimise their asthma control and ensure they have Personalised Asthma Action Plans (PAAP) now.

SELF-MANAGEMENT

Regularly supported self-management is effective.17 The focus of education and support will depend on the child’s age and ability to understand; it is essential to involve both the child and parent/s in a personalised approach. Any language barrier must be addressed, often family members who speak English will attend to help or interpretation services can be used. Remember to consider the child and parents’ lifestyle and address relevant issues such as home situation, hobbies, parents’ work and school. Every child with asthma must have a Personalised Asthma Action Plan and they/their family understand how to use it.6,7,9 The plan itself is a useful educational tool that can be used to guide education. PAAPs should have sections clearly identifying good asthma control (what every patient should be aiming for), worsening asthma (warning signs) and an asthma attack (emergency). These sections can be discussed during the consultation and advice around actions to take specified. For tips on completing asthma action plans, see Resources.

CONCLUSION

Asthma is common in children but getting the diagnosis right is of prime importance. A structured clinical assessment provides a solid foundation in the diagnostic process but once a child is able to perform objective tests, these must be carried out to confirm the diagnosis. ICS remains the cornerstone of asthma management and most children with asthma respond well to very-low or low doses. There are options for add-on therapy in those children who are not completely controlled on ICS alone but specialist paediatric opinion should be sought if there is difficulty gaining control with standard treatment. Inhaler technique is a key issue in paediatric asthma management and careful assessment is essential in every child with poor asthma control. Self-management support is an ongoing process and includes tailored education in addition to the development of a personalised Asthma Action Plan. The Ask About Asthma Campaign offers valuable advice and resources for supporting children with asthma at this time of year.

REFERENCES

1. Looijmans-van den Akker I, van Luijn K, Verheij T. Overdiagnosis of asthma in children in primary care: a retrospective analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66(644): e152-e157. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16x683965

2. Asthma UK. Asthma facts and statistics; 2021 https://www.asthma.org.uk/about/media/facts-and-statistics/

3. Balfour-Lynn IM. Medicolegal issues for the respiratory paediatrician. Paediatr Respir Rev 2017; Oct 12:S1526-0542(17)30091

4. Najaf-Zadeh A, Dubos F, Pruvost I, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of paediatric malpractice claims in France. Arch Dis Child 2010;96(2):127-130.

5. NMC. The Code: Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates; 2018 London:NMC.

6. NICE NG80. Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management; 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80

7. NHS. Update on Quality Outcomes Framework for 2021/2022; 2021 https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/update-on-quality-outcomes-framework-changes-for-2021-22/

8. NHS. The NHS Long Term Plan; 2019 https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/

9. BTS/SIGN. British guideline on the management of asthma; 2019. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

10. Murray C, Foden P, Lowe L, et al. Diagnosis of asthma in symptomatic children based on measures of lung function: an analysis of data from a population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2017;1(2):114-123

11. ARTP. Spirometry: overview; 2021 https://www.artp.org.uk/Spirometry-Overview

12. Ram J, Pineda-Cely J, Calhoun W. Forced Oscillometry: A New Tool for Assessing Airway Function—Is It Ready for Prime Time?. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7(8):2861-2862.

13. UK Inhaler Group. Inhaler standards and competency document; 2016 https://www.ukinhalergroup.co.uk/

14. Plaza V, Giner J, Rodrigo G, et al. Errors in the Use of Inhalers by Health Care Professionals: A Systematic Review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6(3):987-995.

15. Brand P, Makela M, Szefler S, et al. Monitoring asthma in childhood: symptoms, exacerbations and quality of life. Europ Respir Rev 2015;24(136):187-193.

16. Papadopoulos N, Mathioudakis A, Custovic A, et al. Childhood asthma outcomes during the COVID"19 pandemic: Findings from the PeARL multi"national cohort. Allergy 2021;76(6):1765-1775.

17. Hodkinson A, Bower P, Grigoroglou C, et al. Self-management interventions to reduce healthcare use and improve quality of life among patients with asthma: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;370:m2521.

Related articles

View all Articles