Anti-inflammatory reliever therapy for asthma: putting evidence into practice

Beverley Bostock

Beverley Bostock

RGN MSc MA QN

Advanced Nurse Practitioner in long-term conditions, Mann Cottage Surgery

Asthma Lead for the Association of Respiratory Nurses

Practice Nurse 2023;53(5):26-30

A simpler approach to asthma management is supported by evidence and international guidelines, and may prove more acceptable to patients, encouraging adherence and improving outcomes

In a recent editorial, I highlighted the pressure that general practice nurses (GPNs) are under and discussed how we might try to simplify what we do.1 As an example, I mentioned the new approach to asthma management using anti-inflammatory reliever (AIR) therapy. In this article we discuss the evidence for AIR and explain how to move people from short-acting beta2 agonist (SABA) therapy alone to AIR and explain how to introduce AIR as a first-line treatment for asthma. We also address the importance of knowing when to move from AIR to MART (Maintenance and reliever therapy) and beyond.

WHAT IS AIR?

Anti-inflammatory reliever therapy merges the science of asthma management with the art of understanding human behaviour. Evidence suggests that people living with asthma (as in other long-term conditions) struggle with adherence to fixed medication regimes,2 and that empowering people to feel in control may be the key to optimising adherence.3 At the same time, we sometimes see overuse (and overprescribing) of some drugs, notably short-acting B2 agonists (SABAs) in asthma, which has been associated with an increased risk of asthma exacerbations and even death.4 The AIR approach means that people use their combination inhaler, which contains both an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a fast-onset, long acting beta2 agonist (LABA) – formoterol – to both relieve asthma symptoms and to treat the underlying inflammation with the ICS component. Although previous practice has been to give regular ICS therapy in order to resolve the underlying inflammation in asthma, studies have shown that both fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) levels and sputum eosinophils can be reduced as soon as six hours after a single dose of inhaled budesonide.6 This, along with other studies has enabled the licensing of an ICS/formoterol combination inhaler to be used as an anti-inflammatory reliever. The licence was given for the use of the Symbicort 200/6mcg Turbohaler, to be taken as one puff as needed. It should be noted that although there are other ICS/formoterol combination inhalers available, none of the others is licensed for the AIR approach.

WHERE’S THE EVIDENCE?

The Novel START, SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2 studies all support the use of AIR.7,8,9 Novel START showed that severe exacerbations in people using AIR were 56% lower than in the ICS plus prn SABA-only group and that the overall mean daily dose of ICS using AIR was 52% lower than in the standard treatment group.7 Annual asthma exacerbation risk in adults and adolescents was no greater using the AIR approach compared with using an ICS and a SABA. The use of dry powder inhalers (DPIs) is also associated with the potential to have a reduced impact on the environment, compared with other inhaler types, especially pMDIs.

A recent Cochrane meta-analysis, which reviewed five randomised controlled trials of as needed ICS/formoterol involving 9,657 patients, concluded that as required ICS/formoterol was clinically effective in adults and adolescents with mild asthma and when compared with a SABA alone, reduced exacerbations, hospital admissions or unscheduled healthcare visits, average exposure to ICS and exposure to systemic corticosteroids, and was unlikely to be associated with an increase in adverse events.10

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines have, for several years now, suggested that an ‘as required’ ICS/formoterol combination should be prescribed first line for asthma in order to offer symptom relief while concurrently treating the underlying inflammation.11 These guidelines state that as-needed low dose ICS/formoterol should be the preferred reliever for adults and adolescents with asthma, across the range of asthma severity, from GINA step 1 to step 5. They also underline the fact that SABA reliever alone should not be used in asthma. The Primary Care Respiratory Society has published recommendations on the use of GINA guidelines and starting treatment for asthma with an ICS/formoterol combination.12

In a recent webinar, Professor Richard Beasley stated that the justification that all patients must have access to SABA for self-administration only stands if there is no alternative. However, ICS/formoterol reliever therapy is an alternative, and is more effective and safer than using a SABA as a reliever. Professor Beasley is the author of the New Zealand Asthma Guidelines.13

In the United Kingdom, the last update of the asthma guidelines was in 2019.14 The anticipated British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network/National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (BTS/SIGN/NICE) collaborative guideline will not be published for almost a year, so GPNs may well need to look to guidance from GINA and from the New Zealand recommendations in the meantime. Following the introduction of the New Zealand guidelines supporting the use of AIR and MART, prescribing of SABAs has reduced in New Zealand, while the use of Symbicort (as it is the only one with an AIR licence) has increased.15

WHEN AND HOW SHOULD WE MOVE FROM AIR TO MART?

For those people who only use a SABA for occasional or seasonal symptoms, switching to AIR makes clinical sense. The clever thing about AIR is that people use more ICS/formoterol when they need it and less when they do not, so they will step their treatment up and down spontaneously. However, it is worth reminding them that if they need to use their reliever doses regularly, they might be best moving to maintenance and reliever therapy (MART). People starting on AIR should be advised to take no more than six inhalations in one go and no more than 12 inhalations maximum in a day. However, anyone using more than eight inhalations daily, should be advised to seek urgent advice.

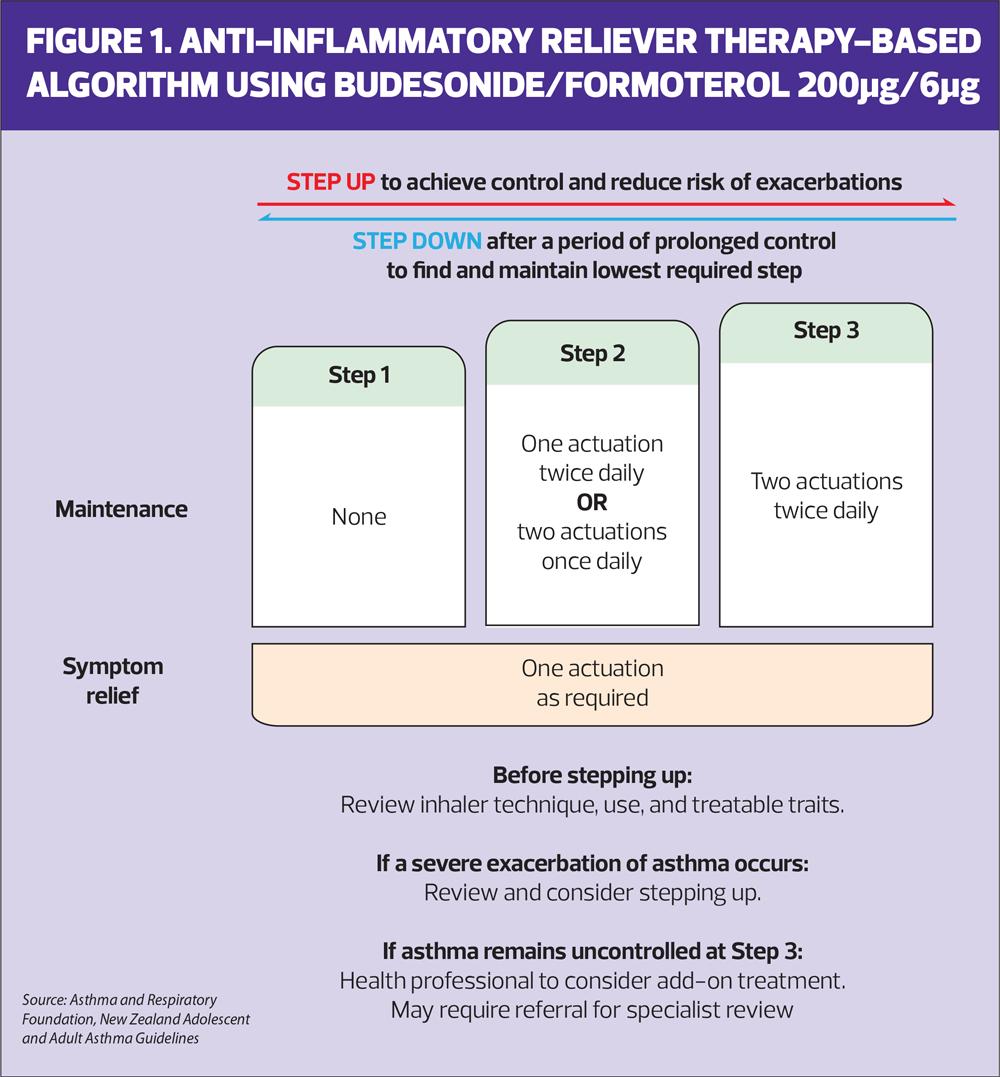

MART involves taking one inhalation twice daily of their ICS/formoterol combination inhaler and then taking extra doses as needed. People using Symbicort can use up to a maximum of 12 doses a day in total. Other MART therapies are available including Duoresp, Fobumix and Fostair, but these are not licensed for AIR. If Fostair MART is used, the maximum number of doses per day should be eight. Duoresp and Symbicort are licensed to use as MART from the age of 12, Fostair and Fobumix are licensed from age 18. Figure 1 from the New Zealand guidelines, shows how treatment can be stepped up and down from AIR to MART and back.

SUPPORTING PATIENTS TO CHANGE TO EVIDENCE-BASED MANAGEMENT

In studies where comparisons were made between standard asthma therapy and AIR, 90% of participants preferred the ‘as needed’ approach.16 Indeed, it could be argued that people with asthma have been using their inhalers this way for some time. Nonetheless, there is no doubt that a proportion of people living with asthma (and some clinicians) may struggle with the concept of giving up the blue inhaler, especially if that is all that they are using. It is important to recognise, then, that the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) clearly identified the risks of so-called mild asthma, with 9% of people dying of asthma allegedly having mild disease and 25% of asthma exacerbations occurring in this group.5 Furthermore, NRAD demonstrated that in cases where people died from their asthma, there was evidence of overuse of reliever medications along with significant under-prescribing of ICS therapy. It is vital, then, to present a confident explanation to patients about why the move to AIR or MART would be recommended, based on the evidence. Patients need to know that for most people formoterol will work as quickly as a SABA for symptom relief but will also last longer, plus they will get a dose of anti-inflammatory medication which will get to the cause of their asthma symptoms.

In a study by Kearns et al, 200mcg of salbutamol 200mcg was shown to have a faster onset of bronchodilator action than budesonide/formoterol 200/6mcg, but importantly had no difference in terms of how it relieved symptoms of breathlessness.17 When patients were asked about their perception of symptom relief when using budesonide/formoterol compared to their previous reliever, almost 4 in 10 people said it worked faster and just over 1 in 3 said it worked the same, leaving only 1 in 3 who thought using ICS/formoterol had a slower onset than salbutamol.

If people are particularly anxious about giving up their blue reliever, it might be worth advising them to use their ICS/formoterol for symptom relief first and then wait for a few minutes to see if they still ‘need’ their SABA. It is likely that they will realise that the ICS/formoterol inhaler provides effective symptom relief.

It is also important to point out the potential side effects of SABA use. In a study by Kearns et al, reported side effects of repeated doses of salbutamol included reduced serum potassium, an increase in heart rate of around 10 bpm, prolonged QT interval, light-headedness and tremor.17

EXACERBATIONS

Clinicians working with people living with asthma need to explain that using the AIR approach means that they are less likely to exacerbate. The AIR approach means that they use one actuation for relief whenever needed, which in turn means that the number of doses needed is a guide to the severity of their asthma at any given time.

In exacerbations of asthma, the current default treatment is salbutamol delivered via a pMDI and spacer, and oral corticosteroids.14 Clinicians and patients may feel that a ‘just in case’ SABA should be provided to all people living with asthma in case of an exacerbation. However, based on the existing research from randomised controlled trials, the advice should be that although AIR reduces the risk of severe attacks, if they do have a flare up of symptoms, they should continue to take their ICS/formoterol and seek urgent medical help, but should not go back to using salbutamol. This advice is included in the New Zealand guidelines. Some clinicians worry about whether patients will be able to use the dry powder inhaler in an exacerbation but a recent study of people attending an emergency department for an asthma attack confirmed that 98% of those assessed were able to generate sufficient inspiratory flow to activate the DPI device.18 Again, it is important to remember that both AIR and MART reduce the risk of having an exacerbation in the first place. In previous studies of MART, people using extra doses of their inhaler were found to recognise poor control and seek medical advice sooner.19 In some people, a move to 2 inhalations twice daily with extra doses as required will be needed, as shown in Figure 1.

Since the guidelines were put into place, hospital admissions for asthma exacerbations and prescriptions for oral corticosteroids in New Zealand have decreased.20

PERSONALISED ASTHMA ACTION PLANS

If people opt to use their ICS/formoterol on a prn basis including, perhaps, for the part of the year when allergic rhinitis or other triggers cause asthma symptoms, their personalised asthma action plan (PAAP) should reflect this and should include a reminder about triggers and trigger avoidance. Their PAAP may reflect the steps of the New Zealand guidelines, as shown in Figure 1. The makers of Symbicort are working on an AIR PAAP, and Asthma + Lung UK (ALUK) is currently developing an AIR action plan. ALUK has recently published a MART action plan, and a free editable version can be downloaded from here: https://shop.asthmaandlung.org.uk/collections/mart-asthma-action-plan/

In New Zealand there is an AIR action plan available online, which may also be worth reading: https://takeyourbreathback.co.nz/assets/Uploads/AIR-Asthma-Action-Plan-v05-copy.pdf

FORMULARIES

Several, but not all, formularies will be up to date with current evidence about AIR. Formulary makers may want to wait to see what NICE has to say about AIR, not least as NICE factors in cost as a significant element of their guidance. As clinicians, GPNs should be aware of the evidence and should always follow the ‘Four Ps’ of the Nursing and Midwifery Code of Conduct: Prioritise people, Practise effectively, Preserve safety, and Promote professionalism and trust. They should also be mindful of the Bolitho Principle when delivering care i.e., that clinical practice must be reasonable and logical. Using the evidence and recommendations described above, there would clearly be a case for arguing in favour of the use of AIR and MART in appropriate patients. Formularies are there to guide but, unlike Bolitho and the Montgomery ruling, which recommends that people are told whatever a reasonable person is likely to want to know about treatment options, they are not the law.

CASE STUDY

Lucy, aged 25, was diagnosed with asthma when she was 15 years old, based on symptoms, a raised FeNO test and obstructive, reversible spirometry. She was previously treated with an ICS and SABA via a pMDI and spacer. She stopped taking her ICS two years ago as her symptoms had resolved. She currently only has intermittent symptoms which tend to occur when she visits her parents, who live on a farm. She also gets some hay fever related wheeze and can also get a tight chest and wheeze when she cycles, although she only does this a few times a year with her friend, who is an avid cyclist. Lucy is new to the practice and has attended for an asthma review. The nurse notes that Lucy is only taking a blue reliever inhaler and that she has ordered three in the past nine months. Lucy explains that she likes to keep one in the car, one in the house and one with her in case something triggers her asthma symptoms.

The nurse explains the changes that happen in the lungs in asthma and describes the new AIR approach to managing symptoms and inflammation with one inhaler. Lucy is worried that her symptoms will not respond to the new inhaler as well as they do to her salbutamol, but the nurse takes time to explain the evidence behind the AIR approach and Lucy agrees to try it. The nurse contacts Lucy a month later to see how she is doing and Lucy reports that she has only used her ICS/formoterol inhaler once in that time but that it did seem to work. She is happy to continue with this approach to treatment.

Three months later, Lucy reports that she has started a new job as a teaching assistant at her local primary school and has suffered regular colds with an increase in her asthma symptoms as a result. She has been using her ICS/formoterol inhaler 3 times a day for symptom relief. Anticipating that this may be related to the September surge, where asthma attacks and admissions rise significantly when children return to school, the nurse congratulates Lucy on using her inhaler flexibly to address her symptoms. She also reminds Lucy that she can consider moving to the next step in her action plan if necessary – i.e., to increase her dose to 1 inhalation twice daily (or 2 once daily) plus extra doses as needed. This ‘maintenance and reliever therapy’ or MART approach will help her to maintain good control of her asthma at this time while giving her the flexibility to move back down to an AIR approach when she feels ready to do so.

SUMMARY

The anti-inflammatory reliever (AIR) therapy approach to asthma management is newly licensed in the United Kingdom but is based on evidence from randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses. In people with ‘mild’ asthma, using AIR and stepping up and down to MART as needed combines a scientific and behavioural approach to providing symptom relief while reducing the inflammation which causes those symptoms. In studies, patients repeatedly indicated their preference for the AIR approach. GPNs need to be confident to recommend AIR and MART as standard care in asthma and to reassure people living with asthma that not only is this a simpler approach with one inhaler and one inhaler technique, it is also linked to a reduced risk of asthma exacerbations, hospital admission and the need for oral corticosteroids.

REFERENCES

1. Bostock B. Let’s make healthcare simpler (editorial). Practice Nurse 2023;53(3):4

2. Bårnes CB, Ulrik CS. Asthma and adherence to inhaled corticosteroids: current status and future perspectives. Respiratory Care 2015;60(3):455–468. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.03200

3. Náfrádi L, Nakamoto K, Schulz PJ. Is patient empowerment the key to promote adherence? A systematic review of the relationship between self-efficacy, health locus of control and medication adherence. PloS one 2017;12(10):e0186458. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186458

4. Molina J, Plaza V, Nuevo J, et al. Clinical Consequences of the Overuse of Short-Acting β2-Adrenergic Agonists (SABA) in the Treatment of Asthma in Spain: The SABINA Study. Open Respiratory Archives 2023;5(2):100232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.opresp.2023.100232

5. Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills: the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) Confidential Enquiry report; 2014. http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/why-asthma-still-kills-full-report.pdf

6. Gibson PG, Saltos N, Fakes K. (2001). Acute anti-inflammatory effects of inhaled budesonide in asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163(1):32–36. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.9807061

7. Beasley R, Holliday M, Reddel HK, et al, Novel START Study Team Controlled Trial of Budesonide-Formoterol as Needed for Mild Asthma. N Engl J Med 2019;380(21):2020–2030. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1901963

8. O'Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, et al. Inhaled Combined Budesonide-Formoterol as Needed in Mild Asthma. N Engl J Med 2018;378(20):1865–1876. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1715274

9. Reddel HK, O'Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, et al. Efficacy and Safety of As-Needed Budesonide-Formoterol in Adolescents with Mild Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021;9(8):3069–3077.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2021.04.016

10. Crossingham I, Turner S, Ramakrishnan S, et al. Combination fixed-dose beta agonist and steroid inhaler as required for adults or children with mild asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev2021;5(5):CD013518. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013518.pub2

11. 2023 GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention; 2023 https://ginasthma.org/2023-gina-main-report/

12. Primary Care Respiratory Society. Focus on asthma: The GINA approach to managing asthma; 2023 https://www.pcrs-uk.org/sites/default/files/resource/2023-May-PCRU-Focus-Asthma-GINA-Approach.pdf

13. Beasley R, Beckert L, Fingleton J, et al. Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ Adolescent and Adult Asthma Guidelines 2020: a quick reference guide. New Zealand Med J 2020;133(1517):73–99.

14. British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. BTS/SIGN British Guideline on the Management of Asthma; 2019 https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

15. Hatter L, Eathorne A, Hills T, et al. Patterns of asthma medication use in New Zealand after publication of national asthma guidelines. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023;11(9):2757–2764.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2023.04.041

16. Baggott C, Reddel HK, Hardy J, et al: PRACTICAL study team Patient preferences for symptom-driven or regular preventer treatment in mild to moderate asthma: findings from the PRACTICAL study, a randomised clinical trial. Eur Respir J 2020;55(4), 1902073. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02073-2019

17. Kearns N, Bruce P, Williams M, et al. Repeated dose budesonide/formoterol compared to salbutamol in adult asthma: A randomised cross-over trial. Eur Respir J 2022;60:2102309. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02309-2021

18. Mohd Rhazi NA, Muneswarao J, Abdul Aziz F, et al. (2023). Can patients achieve sufficient peak inspiratory flow rate (PIFR) with Turbuhaler® during acute exacerbation of asthma?. J Asthma 2023;60(8), 1608–1612. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2023.2169930

19. Patel M, Pilcher J, Pritchard A, et al: SMART Study Group. Efficacy and safety of maintenance and reliever combination budesonide-formoterol inhaler in patients with asthma at risk of severe exacerbations: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine 2013;1(1):32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70007-9

20. Crossingham I, Turner S, Ramakrishnan S, et al. Combination fixed-dose beta agonist and steroid inhaler as required for adults or children with mild asthma. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2021;CD013518. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD013518.pub2

Related articles

View all Articles