Food allergies – what is the best evidence and approach?

Dr Gerry Morrow

Dr Gerry Morrow

MB ChB, MRCGP, Dip CBT

Medical Director and Editor, Clarity Informatics Limited

Food allergies are a relatively common presentation and general practice nurses are a critically important resource for care and diagnosis for patients and their families. This update provides a comprehensive guide to common allergens, typical symptoms and management advice

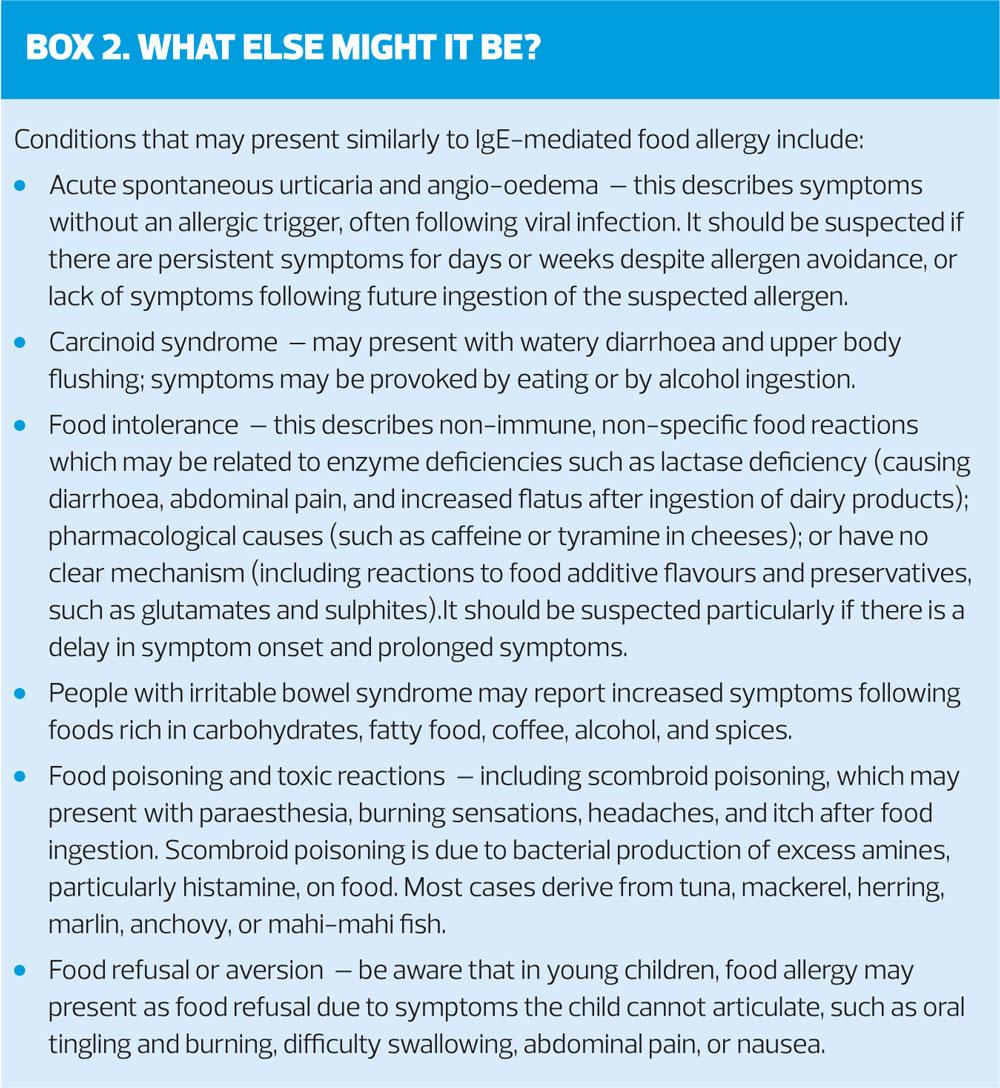

Food allergies affect around 2% of children in the UK, and rather fewer adults. The typical symptoms, including anaphylaxis, are clearly distinguishable from other diagnoses such as food intolerance, food poisoning and irritable bowel syndrome. Less typical presentations may require food diaries, more detailed assessment and referral for allergy testing.

SOME DEFINITIONS

Food allergy describes an adverse immune-mediated response, which occurs when a person is exposed to specific food allergen(s), usually by ingestion and more rarely by inhalation or skin contact.1

Immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated food allergy follows exposure and sensitisation to trigger food allergen(s) causing production of a serum-specific IgE antibody. This produces immediate and consistently reproducible symptoms, which may affect multiple organs including skin, gastrointestinal tract, respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological systems.

Oral allergy syndrome (or pollen-food syndrome) describes a localised food allergy, which may occur due to cross-reactivity between aeroallergens, such as birch pollen, and fresh vegetables, fruits, and nuts. Pollen-sensitised people mount an IgE response to proteins present in fruit and vegetables on oral contact.2

Non-IgE-mediated food allergy involves cell-mediated mechanisms, such as food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome, which tend to occur in young children and presents with gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting with or without diarrhoea, abdominal cramps, colic, and possible faltering growth.

Mixed IgE and non-IgE-mediated food allergy may present as cows' milk protein allergy, eosinophilic oesophagitis, or eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

Food sensitisation describes the production of serum-specific IgE to food allergens, without the clinical symptoms of an allergic reaction on food exposure.

Food intolerances are non-immune adverse reactions to foods and/or food additives, which are distinct from food allergy. They often present non-specifically with gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, fatigue, and musculoskeletal symptoms. Typically, there is a delay in symptom onset and a prolonged symptomatic phase. They may overlap with symptoms of other conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome. The precise cause of food intolerances is unknown, but they may be due to enzyme deficiencies or pharmacological reactions to chemicals such as caffeine or tyramine.

WHAT CAUSES FOOD ALLERGIES?

Allergy may develop to almost any food, but common food allergens include:

- Cows' milk

- Hen's eggs – there is often cross-reactivity between hen’s egg and turkey, duck, and goose egg allergy

- Peanuts, soybeans, peas, and chickpeas – cross-reactivity is uncommon

- Tree nuts (such as walnut, almond, hazelnut, pecan, cashew, pistachio, and Brazil nuts) – there is often cross-reactivity between different tree nuts.

- Crustacean shellfish (such as shrimp, crab, and lobster) and fish – there is often cross-reactivity between different shellfish. There is significant cross-reactivity between different fish species.

- Wheat

- Celery, mustard, sesame, lupine, and molluscan shellfish

Other common cross-reactions include:

- Between peanuts, tree nuts, and sesame.

- 30–50% of people with known latex allergy experience a phenomenon where latex allergens cross-react with plant-derived food allergens, resulting in allergy to banana, kiwi, avocado, tomato, potato, and chestnut, for example (so-called 'latex-fruit syndrome').

- Common raw food allergens for oral allergy syndrome include cross-reactivity between:

– Birch pollen – with apple, pear, peach, plum, cherry, apricot, carrot, celery, parsley, almond, and hazelnut.

– Timothy grass (a common agricultural grass) – with Swiss chard and orange.

Risk factors for the development of food allergy include:

- Known food allergy – the presence of a confirmed food allergy increases the likelihood of additional food allergies.

- Known atopic eczema – the development of early-onset atopic eczema before 6 months of age, and severe eczema below the age of one year, are associated with the development of egg, milk, and peanut allergy.

- Peanut allergy may develop through skin sensitisation in children with an impaired skin barrier function.

- Family history of food allergy – confirmed food allergy in a parent or sibling increases the risk of food allergy.

- Family history of atopy – particularly affecting parents and/or siblings.

HOW COMMON ARE FOOD ALLERGIES?

The best estimate of primary nut allergy is that affects over 2% of children and 0.5% of adults in the UK. Egg allergy most commonly presents in infancy with a prevalence of about 2% in children and 0.1% in adults.3

A prospective survey of hospital admissions for food allergy of 13 million children aged over 10 years reported 0.89 hospital admissions per 100,000 children per year.4 Peanut was the most common trigger allergen (21%) followed by tree nuts (16%).4

WHAT ARE THE COMPLICATIONS OF FOOD ALLERGIES?

The possible complications of food allergy include:

- Severe and life-threatening reactions. Food allergy is the most common trigger of anaphylaxis in the community. The risk of anaphylaxis depends on the specific food allergy – allergy to peanuts, tree nuts, fish, and shellfish are associated with a higher risk of anaphylaxis. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 European studies found the incidence rate of fatal food anaphylaxis in people with food allergy was 1.81 per million person-years.5

- Stress and anxiety (affecting the child, adult, and parents/carers). This may be associated with the need for constant vigilance over food choices, and risk of accidental food exposure and severe reactions.

- Reduced quality of life. Dietary restrictions affect food shopping and family meals, which may be stressful and time-consuming. There is potential impact on social interactions, such as eating out, playing at friends' houses, attending birthday parties, and possible issues with peer pressure, stigma, and embarrassment.

- Restricted diet and malnutrition. The risk of inadequate nutritional intake and faltering growth in children, if food allergens that contribute essential nutrients are eliminated.

WHAT IS THE PROGNOSIS WITH FOOD ALLERGIES?

The prognosis of food allergy depends on the person's age, co-morbidities, and specific causal food allergen. Most children outgrow their food allergy over time.6

One study of children with confirmed egg allergy found that tolerance had developed in 4% of children by 4 years of age; 26% by 8 years; 48% by 12 years; and 68% by 16 years of age.7

A retrospective study of children with wheat allergy found that tolerance had developed in 29% of children by 4 years of age; 56% by 8 years; and 65% by 12 years.8

Some food allergies are most likely to persist, such as peanuts, tree nuts, fish, and shellfish.2,6

Factors which may increase the likelihood of severe food allergy and/or anaphylaxis include:

- A history of asthma, especially if poorly controlled.

- A history of other atopic disease, such as atopic eczema or allergic rhinitis.

- A history of previous systemic allergic reaction.

- Allergy to the food classes of peanut, tree nut, fish, or shellfish.

WHEN SHOULD I SUSPECT FOOD ALLERGY?

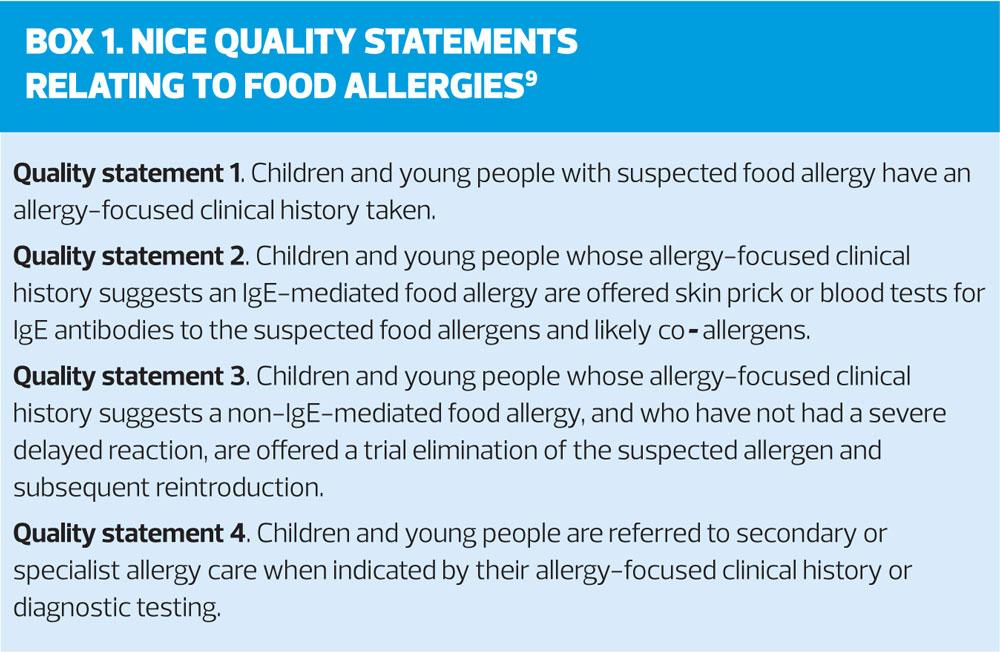

Practice nurses should suspect a diagnosis of immediate IgE-mediated food allergy if there are typical clinical features:

- Classical symptoms that develop within seconds or minutes to 1–2 hours after ingestion of a specific trigger food, and typically resolve within 12 hours.

- Systemic – respiratory distress, severe wheezing, hypotension, tachycardia or bradycardia, drowsiness, confusion, collapse and loss of consciousness, which suggests life-threatening anaphylaxis.

- Skin – urticaria, angio-oedema (most commonly of the lips, face, and around the eyes), erythema, generalized itching, and flushing.

- Respiratory – persistent cough, hoarseness, wheeze, breathlessness, stridor; nasal discharge, congestion, itching, and sneezing.

- Gastrointestinal – nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain.

Symptoms suggesting a diagnosis of oral allergy syndrome (pollen-food syndrome) or latex-fruit syndrome:

- Oral allergy syndrome – typically mild, transient, localized urticaria and associated tingling, itching, and swelling of the lips, tongue, and throat, often with co-morbid allergic rhinitis symptoms which are worse with a high pollen count.

- Latex-fruit syndrome – people with known latex allergy may present with symptoms including urticaria, angio-oedema, oral symptoms, or anaphylaxis following ingestion of certain fruits and nuts.

Note: be aware that a diagnosis of primary nut allergy and oral allergy syndrome may co-exist.

Consider a diagnosis of food allergy in people who have unexplained persistent symptoms of atopic eczema or faltering growth

HOW SHOULD I ASSESS A PERSON WITH SUSPECTED FOOD ALLERGY?

If a diagnosis of immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated food allergy is suspected based on reported or observed clinical features, ask about:

- Possible causal food or foods

- Symptoms, frequency, speed of onset, duration, and the timing of the reaction in relation to the suspected allergen exposure. A food and symptom diary may be helpful

- Form and quantity in which the food has been eaten

- Any uneventful exposures to the suspected allergen before or after the reaction

- The setting of reactions (such as school or home)

- The reproducibility of symptoms on repeated food exposure

- Age when symptoms started, the person's feeding history (age of complementary feeding [weaning], breast- or formula-fed), weight gain, and nutritional status

- Any co-factors which may increase the likelihood of a clinical reaction: age, exercise, menstruation, stress, infection; ingestion of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or alcohol

- Any co-morbid atopic conditions

- Any family history of food allergy or atopic conditions, particularly in parents and siblings

- Any symptom response to dietary restrictions or reintroduction of foods, and/or medications tried.

And examine the person for:

- Nutritional status, including weight, length/height, and calculation of body mass index

- Any signs of a clinical reaction

- Any signs of co-morbid conditions such as asthma, atopic eczema or allergic rhinitis

Arrange for skin prick testing and/or serum-specific IgE allergy testing to the suspected food allergens and likely cross-reactive foods.

Advise the person that the following diagnostic tools are not recommended for the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy:

- Serum-specific immunoglobulin (Ig)G testing

- Trial food elimination diet (although this may be helpful in the diagnosis of non-IgE-mediated food allergy, under dietetic supervision)

- Vega testing (electroacupuncture devices)

- Applied kinesiology (muscle strength testing)

- Hair analysis (assessing mineral content).

There is no evidence that any of these provide any scientific benefit whatsoever.

HOW SHOULD I MANAGE A PERSON WITH A SUSPECTED FOOD ALLERGY?1,10

Arrange immediate ambulance transfer to A&E if they have systemic symptoms or suspected anaphylaxis, with or without angio-oedema.

Arrange referral to an allergy specialist for further assessment and management, if the person has had one or more episodes of systemic symptoms consistent with a severe reaction or the person is at increased risk of anaphylaxis, such as a history of food allergy and co-morbid persistent or poorly controlled asthma; or a severe reaction to a trace amount of food allergen (airborne or contact through skin only).

Allergy testing is needed to confirm the diagnosis, or to assess whether tolerance has developed to a specific food allergen, depending on local referral pathways and availability if:

- The diagnosis is uncertain

- There are multiple suspected food allergies

- There is significant atopic eczema, where multiple or cross-reactive food allergies are suspected

- There is persistent food allergy beyond the age of expected tolerance, or adult-onset allergy

- There is persistent parental or carer suspicion of food allergy (particularly if there are difficult or perplexing symptoms) despite a lack of supporting history, or persistent anxiety about the diagnosis of food allergy

Arrange referral to a paediatric dietitian or dietitian if:

- There are concerns about faltering growth, excessive weight gain, nutritional status, or inappropriate dietary restriction

- Advice on specific food allergen avoidance is needed

- Advice on food reintroduction is needed

- The person is already on a restricted diet, for cultural or religious reasons.

ALLERGY TESTING IN FOOD ALLERGIES

Allergy testing may involve initial skin prick testing or measuring serum-specific immunoglobulin (Ig)E levels to different food allergens.

Both allergy tests are sensitive but not specific and have various limitations and potential difficulties in interpretation. Note: atopy patch testing is not recommended for the routine assessment of suspected food allergy.

Allergy testing may also be used to assess whether tolerance has developed in a person with a confirmed food allergy. The optimal interval for follow-up testing partly depends on the specific food allergen:

- For egg, soybean, or wheat allergy, testing every 12–18 months up to the age of 5 years, and every 2–3 years following this, may be recommended

- For peanut, tree nut, fish, and shellfish allergy, testing every 2–4 years may be recommended.

If the results of allergy testing do not correspond with the clinical history, an oral food challenge may be needed to confirm the diagnosis, this is the gold standard for diagnosis of food allergy and is an accurate and sensitive test. It involves the administration of increasing quantities of the food allergen, starting with direct mucosal exposure and then titrated as tolerated. If symptoms are not provoked, the test is negative and clinical allergy can be excluded.

SELF-MANAGEMENT AND FOLLOW-UP

Practice nurses are ideally placed to ensure a person with a confirmed diagnosis of food allergy has an individualised written allergy management plan.

Provide advice on sources of information and support, such as:

- Allergy UK factsheets.

- British Dietetic Association patient leaflets.

- Patient information leaflets available from www.patient.info

Provide written advice on prompt recognition and management of acute symptoms following accidental or new exposures. If the person has:

- A history of anaphylaxis or a suspected acute systemic reaction

- Mild or moderate symptoms – advise on the immediate use of an oral non-sedating antihistamine such as cetirizine or loratadine, to be taken 'as-needed'. In infants and children aged less than two years the sedating antihistamine chlorphenamine may be used instead.

- Oral allergy syndrome – advise on the additional management of co-morbid allergic rhinitis symptoms.

Provide advice and education on food allergen avoidance, to help the person make safe and appropriate food choices, which may include:

- Which foods and drinks to avoid, including foods that may be cross-reactive and any suitable alternatives.

- Confirmed allergy to a specific tree nut or shellfish may require avoidance of all food allergens in these classes unless they are known to be tolerant or have had negative allergy tests.

- How to check and interpret food labels and recognise food allergens in ingredients lists of food products. This includes lists of alternative terms for specific food allergens (such as ovalbumin) and advice on precautionary allergen labelling.

- Advise that loose foods (for example bought from markets) and foods imported from outside the EU, may not have food ingredient labelling, and may be best avoided.

- Awareness of possible cross-contamination of foods with allergens during food manufacture, preparation, and serving.

- Awareness of situations when accidental exposure is more likely, such as in nursery/school, when eating out, birthday parties, friends' houses, or when travelling.

ANNUAL REVIEW

Practice nurses are well-placed to ensure that the person is reviewed by a specialist or in primary care at least annually, to:

- Review symptoms, any accidental exposures or reactions

- Assess for any new-onset food allergies

- Assess the person's dietary intake and nutritional status

- Reinforce the importance of allergen avoidance strategies

- Check for the development of new co-morbidities such as asthma or eczema, whether symptoms are controlled, and the risk of anaphylaxis

- Arrange specialist allergy clinic referral, for example for repeat allergy testing to assess whether tolerance has developed to a specific food allergen

- Arrange dietitian referral for monitoring of growth and nutrition, or advice on food reintroduction, if needed

- Update the individualised written allergy management plan, as appropriate.

CASE STUDY

Amy is a 12-year-old girl who attends for her regular asthma clinic appointment with her mother. During the consultation she mentions that she has developed a rash and swollen lips at times and wonders whether it is a reaction to her inhaled medication. When you ask her about the rash and lip swelling it appears that it often happens after meals.

You ask her to keep a food diary and review her in two weeks’ time.

At her next appointment you read over the contents of her food diary. You note that the swelling and rash appear to occur most Friday evenings. At the same time, her night-time cough is also worse on those evenings. Amy tells you that they often have chips for dinner on a Friday evening from the local fish shop. She does not eat fish but shares food with her brother who does eat fish.

You suggest that on the next Friday meal that she has a cetirizine tablet either before the meal or if symptoms develop. You also suggest that her chips are kept separate from any fish.

One month later Amy attends for a routine appointment. She tells you that the swelling has not recurred as she has used the antihistamine to prevent the allergy symptoms. She does occasionally have a night-time cough on Fridays and Saturdays. Amy’s mother is concerned about the asthma symptoms being related to the allergy. As a result, you suggest that she ask the GP for a referral for allergy testing.

CONCLUSION

Food allergies are a relatively common problem presenting to primary care and emergency care nurses. The typical symptoms including anaphylaxis are clearly distinguishable from other diagnoses such as food intolerance, food poisoning and irritable bowel syndrome. Less typical presentations may require food diaries, more detailed assessment and referral for allergy testing. Practice nurses are ideally placed to provide patients with possible food allergies with advice, support and are critically important resource for care and diagnosis for patients and their families.

REFERENCES

1. NICE CG116. Food allergy in under 19s: assessment and diagnosis, 2011.

2. Stiefel G, Anagnostou K, Boyla RJ, et al BSACI guidelines for the diagnosis and management of peanut and tree nut allergy. Allergy 2017;47(6):719-739

3. Nwaru BI, Hickstein L, Panesar SS, et al. Prevalence of common food allergies in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2014;69(8):992-1007

4. Colver AF, Nevantaus H, Macdougall CF, et al. Severe food-allergic reactions in children across the UK and Ireland, 1998-2000. Acta Paediatrica 2005;94(6):689-695

5. Umasunthar T, Leonardi-Bee J, Hodes M, et al. Incidence of fatal food anaphylaxis in people with food allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Allergy 2013;43(12):1333-1341

6. Longo G, Berti I, Wesley Burks A, et al. IgE-mediated food allergy in children. Lancet 2013;382(9905):1656-1664

7. Savage JH, Matsui EC, Skripak JM, et al. The natural history of egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120(6):1413-1417

8. Keet CA, Matsui EC, Dhillon G, et al. The natural history of wheat allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2009;102(5):410-415

9. NICE QS118. Food allergy, 2016.

10. Boyce JA, Assa'ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126(6):S1-S58.

Related articles

View all Articles