Allergic disease:diagnosis and management for general practice

Beverley Bostock

Beverley Bostock

RGN MSc MA QN

Advanced Nurse Practitioner

Mann Cottage Surgery

Association of Respiratory

Nurse Specialists

Primary Care Respiratory Society

Practice Nurse 2024;54(2):23-27

One in five people may be affected by allergic disease, such as asthma, eczema, and allergic rhinitis, and testing for specific allergens can guide pharmacological and non-pharmacological management to reduce symptoms and improve patients’ quality of life

Allergic diseases are common, affecting at least 20% of the population.1 Types of allergic disease include asthma, eczema, allergic rhinitis (AR), nasal polyps and food allergy. The process by which allergic reactions happen is often referred to as the allergic cascade, with the relationship between these diseases being called the atopic march.2 Testing for allergic disease can facilitate both the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of the allergy, reducing the symptom burden and improving quality of life. The focus of this article is on the identification and management of aeroallergens.

THE ALLERGIC CASCADE EXPLAINED

Allergic disease involves multiple elements including mast cells, histamine, T2 helper (Th2) cells, eosinophils, cytokines – such as interleukins, and immunoglobulins, all of which have led to an increased recognition of the different phenotypes of allergic disease.3 In asthma, for example, common phenotypes may be described as Th2 or non-Th2 or as T2 high or T2 low.4 Understanding more about the pathways which lead to allergic symptoms can support the development of tests to identify which aspect to focus on in terms of avoidance of triggers and the most appropriate pharmacological interventions to reduce symptom burden.

Allergens produce and release immunoglobulins (IgE) with a specific IgE being produced for each allergen. This activates the Th2 pathway, which also involves interleukins – specifically IL4, IL5 and IL13. IL5 is important for eosinophil synthesis, IL4 helps the eosinophils to mature and IL13 is key to eosinophil recruitment.3 The Th2 pathway is also linked to fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) levels. The concept of the allergic cascade has now been augmented by discoveries about the role of epithelial-driven disease in allergic asthma.3 As a result, newer molecules have been recognised in the development of allergic asthma. These are known as alarmins, which are released as a response to damaged bronchial epithelium. Research into pharmacological interventions which can target alarmins is ongoing.5

THE BURDEN OF ALLERGIC DISEASES

Statistics vary with respect to the prevalence of allergic disease with people living in the UK often reporting a higher level of symptoms than in other countries. Around 10-40% of people with AR have asthma, while between 6-85% of people with asthma have nasal symptoms.6,7 For many people, their allergy can have a profound effect on their quality of life with symptoms including wheezing, sneezing, cough, tight chest, rhinitis, sinusitis, rashes, itching nose, eyes, mouth or palate, and diarrhoea and/or vomiting.

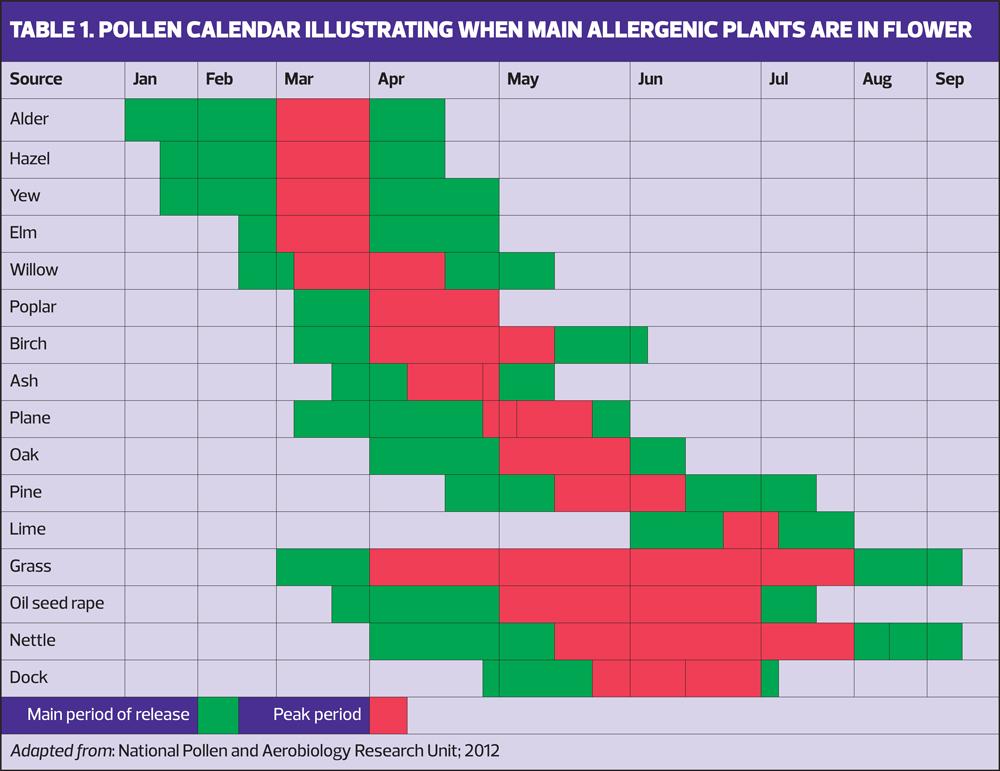

People with food allergies will also need to check ingredients and carry epinephrine pens with them in case of accidental ingestion of allergy-causing foods leading to anaphylaxis.8 Hay fever can affect performance at school or work, and impair sleep.9,10 It can also increase the risk of asthma symptoms, exacerbations and even death in people with both conditions.11,12 In the majority of asthma sufferers, their asthma has an allergic component, which increases symptoms based on seasonal or perennial triggers. Airborne allergens are an important cause of asthma exacerbations and although avoidance of allergens is always recommended, this is not always possible, especially if the allergen has not been identified.

WHEN TO TEST FOR ALLERGIES

Taking a good history is essential when considering allergy-related conditions as a possible diagnosis. Although allergy testing can be useful in helping to define the allergen or allergens responsible for symptoms, the choice of which allergens to test for will depend on the history. Patients should be asked about the possibility of allergic symptoms with a focus on the presence of symptoms, such as rhinitis, sneezing, blocked nose, itchy eyes or itchy nose, or increased asthma symptoms in response to exposure to triggers or changes in the season.13

In asthma, the diagnosis is made based on a history of intermittent symptoms of cough, wheeze, breathlessness and/or tight chest with evidence of reversible airways disease, raised blood eosinophils and/or FeNO levels.7,13 NICE recommends asking about symptoms and any personal or family history of allergies, atopic disorders or asthma. NICE also recommends allergy testing in people with asthma, stating that skin prick tests to aeroallergens or specific IgE tests should be used to identify asthma triggers once the diagnosis of asthma has been confirmed.14

International guidelines on allergic rhinitis recommend that the diagnosis should be suspected if at least two of these symptoms are present for at least one hour on most days when related to allergen exposure.15 The confirmation of an allergic basis for the symptoms can be made using objective tests, including an IgE blood test and/or skin prick testing for suspected allergens.16 Specific IgE testing will help to identify the allergen more precisely.17

A robust history will ensure that the relevant specific IgE levels are requested, reducing the risk of missing a diagnosis by failing to identify the most likely allergen.

HOW TO TEST FOR ALLERGIES

The most common test used in primary care to assess for allergy is to measure IgE levels, including testing for specific IgE such as animal dander, pollen, mould, house dust mites and foods. Other tests might include skin prick testing (SPT), intradermal testing and patch tests.

IgE levels and eosinophils may point to the likelihood of an allergic basis for symptoms, but they will not identify the exact allergen causing the symptoms. To do that, measurement of specific IgE (sIgE) is needed, and these blood tests can be requested for particular allergens, based on the history. Laboratory blood test results are available approximately 4-6 weeks after the sample is taken, although if point-of-care testing is used, the results are available within 20 minutes. If patients are taking an antihistamine for allergic symptoms, it will not interfere with the IgE levels so will not impact on the results.

SPT is usually carried out in a specialist setting. It involves lightly scratching the skin and applying an allergen before assessing the site after around 20 minutes. A positive test is recorded if a wheal of 3mm or larger appears at the test site. SPT is not foolproof, however, so any diagnosis should be made through consideration of the history along with the IgE levels.18

Patch testing is also normally carried out in secondary care. This requires a patch with the allergen on it to be applied to the skin for 48 hours, with any reaction recorded when the patch is removed.

Direct allergy testing (SPT, patch tests, and challenge tests) can be potentially harmful as the patient is being exposed to the very substance that is thought to be responsible for their symptoms. The risk of a severe reaction, including anaphylaxis, will be carefully managed in the specialist setting. In contrast, IgE testing simply measures the level of IgE produced to a suspected allergen reaction, so it will not cause an acute response. This is why measuring IgE is a simple test for primary care to carry out in order to inform the management of allergy-related conditions.

ACTING ON RESULTS

Managing allergic disease will require a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Avoidance of allergens is key, although this may not always be possible. However, knowing which allergens are causing symptoms can significantly increase the possibility of avoiding, or at least minimising, contact with the relevant substance.

House dust mite (HDM), explicitly, house dust mite feces, is a common cause of allergic symptoms and limiting the use of soft furnishings (carpets, rugs, cushions and curtains) can help, as the mites live in these places. Washing toys and pillows at high temperatures and replacing them regularly can reduce HDM levels. Vacuuming frequently, using HEPA filters where possible, is also helpful. Anti-allergy bedding, such as mattress covers and pillowcases may be useful, although the evidence is not very strong.19

Immunotherapy for pet allergies may be possible as although avoidance is key, the emotional impact of rehoming a pet may be significant.20 Other options may include reducing pets’ access to all areas of the house and keeping them out of the bedroom. Bathing animals may reduce the amount of dander, which is the cause of animal allergies.

If a mould allergy is identified, improving ventilation to reduce damp and condensation by opening windows or introducing air filters can also help. Indoor plants should be removed and exposure to rotting plants, leaves, vegetables and compost should be minimised.

Advice on pollen allergy should include staying inside during peak pollen times, such as mornings and evenings, avoiding line-drying clothes at this time, keeping doors and windows closed, wearing wraparound sunglasses, showering and changing clothes after exposure to pollen, avoiding parks and grassy areas, and getting someone else to mow the lawn.15 Some people have found that nasal douching or a barrier cream around the nose can help in very mild cases of allergic rhinitis.21

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

If people know that they are likely to be exposed to an allergen, an antihistamine can be taken an hour pre-exposure. This is usually a non-drowsy oral antihistamine (although this will depend on their age). People with asthma should be taking an inhaled corticosteroid complemented, where indicated, by an intranasal steroid (INS).13 Intranasal antihistamines may be more effective than oral antihistamines and the two ingredients are available as a combined product which can help to achieve better symptom control.22 Anyone being prescribed an intranasal spray should be taught how to take it correctly, as demonstrated in this video from Asthma and Lung UK https://www.asthmaandlung.org.uk/living-with/inhaler-videos/nasal-spray.

Intranasal steroids can help with allergic conjunctivitis symptoms too although affected people may also benefit from additional eye drops.23 In people who have been diagnosed with several allergy-related conditions, such as asthma, eczema, and allergic rhinitis, consideration should be given to the steroid load of someone who may be using inhaled, intranasal and topical steroids. INS treatments with low bioavailability (fluticasone propionate, fluticasone furoate or mometasone furoate) should be selected where possible.

Other therapies may also be indicated in allergic asthma such as leukotriene receptor antagonists, which can reduce allergic rhinitis symptoms and improve asthma control.13 Montelukast is licensed for use from age 6 months and above, but prescribers should make patients aware of the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) warning about possible neuropsychiatric effects.24 Long-acting muscarinic antagonists such as tiotropium and biologic therapies should also be considered to improve asthma management, depending on the patient’s history.13 Allergen immunotherapy (AIT) given subcutaneously (SCIT) or sublingually (SLIT) is another potential intervention as it has been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms in allergic asthma, allergic rhinitis and rhinoconjunctivitis, reducing the need for other medication.25

Seasonal asthma can be a challenge, as patients often do not want to take medication every day, all year round, for intermittent symptoms. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidance now recommends prescribing an ‘as required’ ICS/formoterol combination for people with intermittent asthma symptoms, which might be seen in seasonal asthma. The anti-inflammatory reliever (AIR) approach to asthma management offers symptom relief while concurrently treating the underlying inflammation.26 At the time of writing only Symbicort Turbohaler™ 200/6mcg is licensed to be used this way, for people aged 12 and above.

SUPPORTING SELF-MANAGEMENT

Allergy UK has a host of resources that can support people living with allergic conditions.

People with asthma should have an asthma action plan (PAAP) which reflects their current treatment pathway. This includes the AIR approach if they have chosen to use it, with escalation to maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) and de-escalation back to AIR as indicated by symptoms. All PAAPs should also include a reminder about triggers and allergen avoidance.13

The MASK-air app has been designed to enable people living with allergic rhinitis to record and monitor their symptoms in order to manage them more effectively; there is also the ARIA-MASK-air app for people with asthma and coexisting allergic rhinitis.27 The allergic rhinitis visual analogue scale can be used by patients and clinicians to assess symptom burden. It includes a scoring system ranging from 0-10, with a score of zero suggesting that the symptoms are not present or not bothersome at all with a score of 10 indicating that they are extremely bothersome.28 Revisiting the score after a trial of treatment can be very useful in determining its value.

SUMMARY

Research continues into the allergic cascade and the atopic march and as a result, a greater range of pharmacological interventions is likely to be made available to people living with allergic disease. This is important because these conditions are common and carry a heavy burden of morbidity, which affects performance at school or work, impairs sleep and negatively impacts on quality of life. The diagnosis of allergic disease is made through careful history taking along with objective testing. The most common test used in primary care is IgE testing, where specific allergens can be identified through a simple blood test. Once the allergen is known, management will be based on avoidance, where possible. Patients can be supported to recognise the value of interventions such as vacuuming, washing, and choosing home furnishings and may also be relieved to know that they do not necessarily need to rehome an allergy-inducing pet. Pharmacological management can include oral, intranasal and inhaled therapies and some patients with allergic asthma will benefit from the use of biologic therapies designed to address specific pathways within the allergic cascade. There is a range of resources available to support people living with allergic disease to ensure that they can self-manage effectively.

References

1. Dierick BJH, van der Molen T, Flokstra-de Blok BMJ, et al. Burden and socioeconomics of asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and food allergy. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2020;20(5):437–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2020.1819793

2. Cingi C, Gevaert P, Mösges R, et al. Multi-morbidities of allergic rhinitis in adults: European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Task Force Report. Clin Transl Allergy 2017;7:17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13601-017-0153-z

3. Domingo C, Mirapeix RM. From the Allergic Cascade to the Epithelium-Driven Disease: The Long Road of Bronchial Asthma. Int J Molecular Sci 2023;24(3):2716 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032716

4. Kuruvilla ME, Lee FE, Lee GB. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clin Rev Allerg Immunol 2019;56(2):219–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-018-8712-1

5. Gauvreau GM, Bergeron C, Boulet LP, et al. Sounding the alarmins-The role of alarmin cytokines in asthma. Allergy 2023;78(2):402–417 https://doi.org/10.1111/all.15609

6. Brozek JL, Bousquet J, Agache I, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines-2016 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;140(4):950–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.03.050

7. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention; 2023 https://ginasthma.org/2023-gina-main-report/

8. Warren CM, Jiang J, Gupta RS. Epidemiology and Burden of Food Allergy. Current allergy and asthma reports 2020;20(2):6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-020-0898-7

9. Schuler CF, Montejo JM. Allergic Rhinitis in Children and Adolescents. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2021;41(4):613–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2021.07.010

10. Wise SK, Lin SY, Toskala E, et al. International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Allergic Rhinitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2018;8(2):108–352. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22073

11. Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills; 2014 https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills

12. D'Amato G, Vitale C, Molino A, et al. Asthma-related deaths. Multidiscip Respir Med 2016;11:37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40248-016-0073-0

13. British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN 2019) British Guideline on the Management of Asthma https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

14. NICE NG80. Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management; 2017, updated 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80

15. EUFOREA. Pocket guide – allergic rhinitis; 2021

16. Testera-Montes A, Jurado R, Salas M, et al. Diagnostic Tools in Allergic Rhinitis. Front Allergy 2021;2:721851. https://doi.org/10.3389/falgy.2021.721851

17. Griffiths RL, El-Shanawany T, Jolles SR, et al. Comparison of the Performance of Skin Prick, ImmunoCAP, and ISAC Tests in the Diagnosis of Patients with Allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2017;172(4):215–223 https://doi.org/10.1159/000464326

18. Birch K, Pearson-Shaver AL. Allergy Testing In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537020/

19. Salo PM, Zeldin DC. Mite-impermeable bedding casings and severe asthma exacerbations. J Pediatr 2018;192, 266–269 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.10.058

20. Dávila I, Domínguez-Ortega J, Navarro-Pulido A, et al. Consensus document on dog and cat allergy. Allergy 2018;73(6):1206–1222 https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13391

21. Head K, Snidvongs K, Glew S, et al. Saline irrigation for allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;6(6):CD012597. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012597.pub2

22. Hellings PW, Scadding G, Bachert C, et al. EUFOREA treatment algorithm for allergic rhinitis. Rhinology 2020;58(6):618–622. https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhin20.246

23. Dupuis P, Prokopich CL, Hynes A, Kim H. A contemporary look at allergic conjunctivitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2020;16, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-020-0403-9

24. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Montelukast (Singulair): reminder of the risk of neuropsychiatric reactions; 2019 https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/montelukast-singulair-reminder-of-the-risk-of-neuropsychiatric-reactions

25. Boonpiyathad T, Lao-Araya M, Chiewchalermsri C, et al. Allergic Rhinitis: What do we know about allergen-specific immunotherapy?. Front Allergy, 2021;2, 747323. https://doi.org/10.3389/falgy.2021.747323

26. Bostock B. Anti-inflammatory reliever therapy for asthma: putting evidence into practice. Practice Nurse 2023;53(5):26-30

27. Bousquet J, Anto JM, Sousa-Pinto B, et al. Digitally-enabled, patient-centred care in rhinitis and asthma multimorbidity: The ARIA-MASK-air® approach. Clin Transl Allergy 2023;13(1), e12215. https://doi.org/10.1002/clt2.12215

28. Klimek L, Bergmann KC, Biedermann T, et al. Visual analogue scales (VAS): Measuring instruments for the documentation of symptoms and therapy monitoring in cases of allergic rhinitis in everyday health care. Allergo journal international 2017;26(1):16–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-016-0006-7

Related articles

View all Articles