Annual reviews in long term conditions

Katherine Ellerby

Katherine Ellerby

RGN, RM, BSc (Hons),

Non-medical independent prescriber, NDFSRH

Practice Nurse, Framlingham Medical Practice, Suffolk & Clinical Research Nurse, Suffolk Primary Care

A fundamental component of the management of long term conditions is the annual review: how can we ensure that this is more than just a tick-box exercise and contributes to the well-being of our patients?

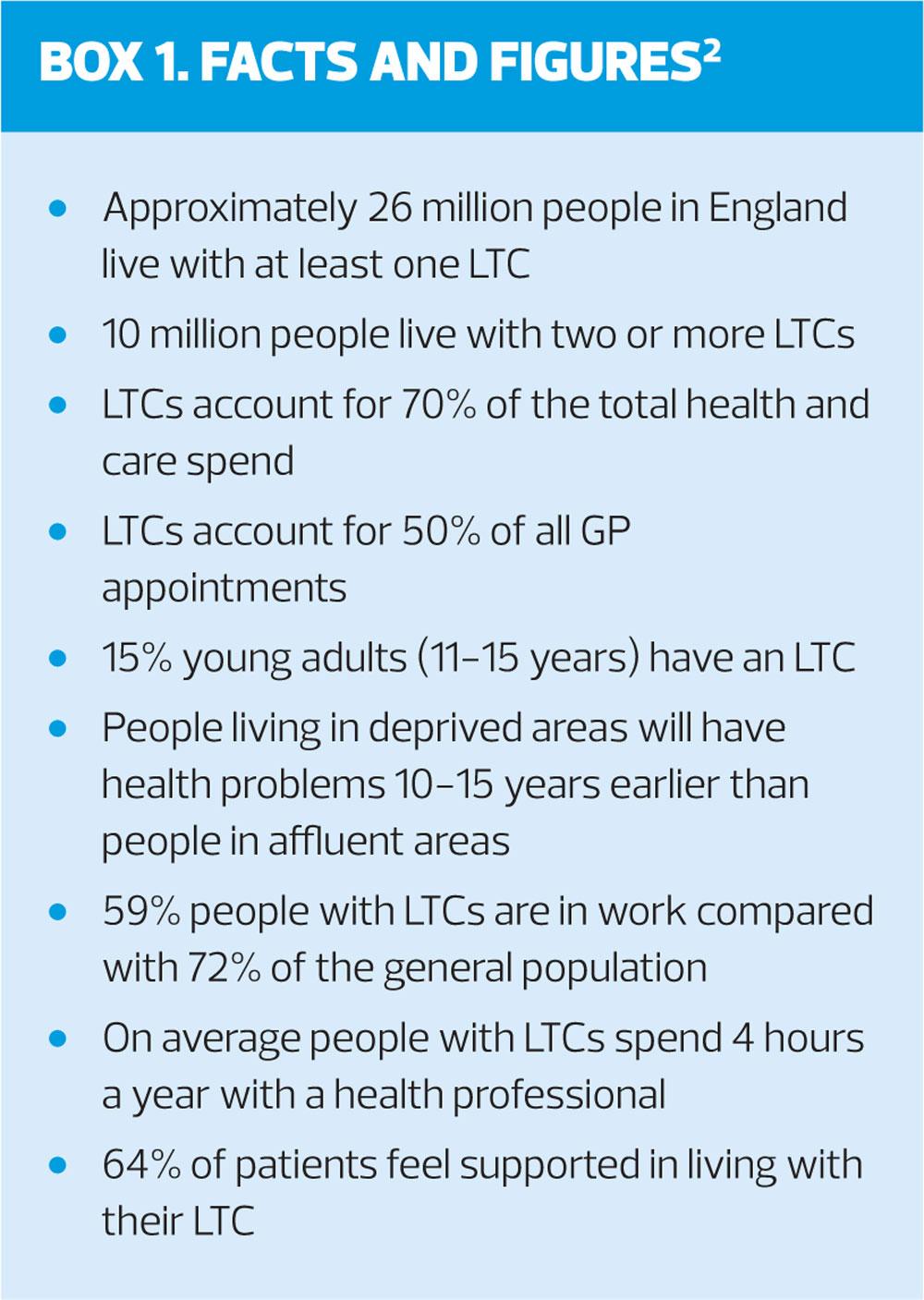

It is a fact of our times that a quarter of adults currently live with two or more long-term conditions (LTCs).1 Such multimorbidity can encompass all manner of mental and physical conditions, which can impact on a person’s health and wellbeing, ranging from cardiovascular disease to schizophrenia.1 Unquestionably, the impact of this pandemic on the NHS purse strings is enormous (Box 1) and improving the management of patients with LTCs is a major focus of the Five Year Forward View.3 Equally, The NHS Long Term Plan published in early 2019 has made a commitment to prioritise major health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer, respiratory conditions, dementias, and adult mental health.4

LONG TERM CONDITIONS

A Long Term Condition (LTC), as defined by the RCGP, is ’any medical condition that cannot currently be cured but can be managed with the use of medication and/or other therapies’.5 In primary care we also need to look beyond medication and therapies and explore how a patient can live their daily life as optimally as possible in spite of their LTC.

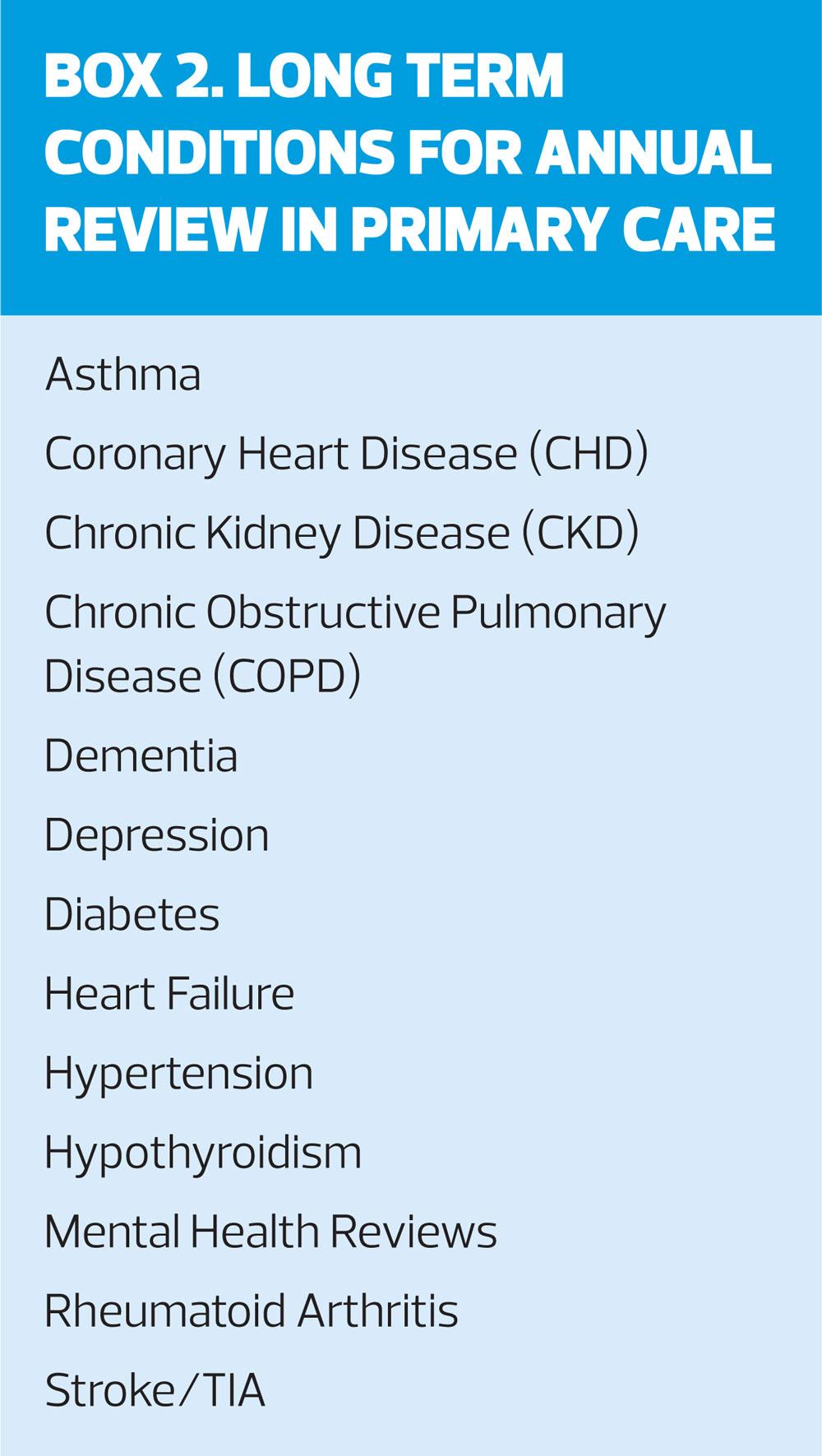

Annual reviews of LTCs conducted by general practice nurses are often split up into disease areas (Box 2), driven essentially by the contractual obligation of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF).6 This review gives us the opportunity to not just ‘tick the boxes’ but to develop a relationship with our patients, understand the impact and burden their ill-health has on their wellbeing and to plan together an ongoing supported self-managed approach to care to improve their quality of life and reduce the risk of crisis management. A person living with an LTC lives with that condition – or conditions – every single day of their life to a greater or lesser extent and, as nurses we need to ensure that our 20-30 minute contact (if we’re lucky) goes some way to improve that daily burden.

ANNUAL REVIEWS

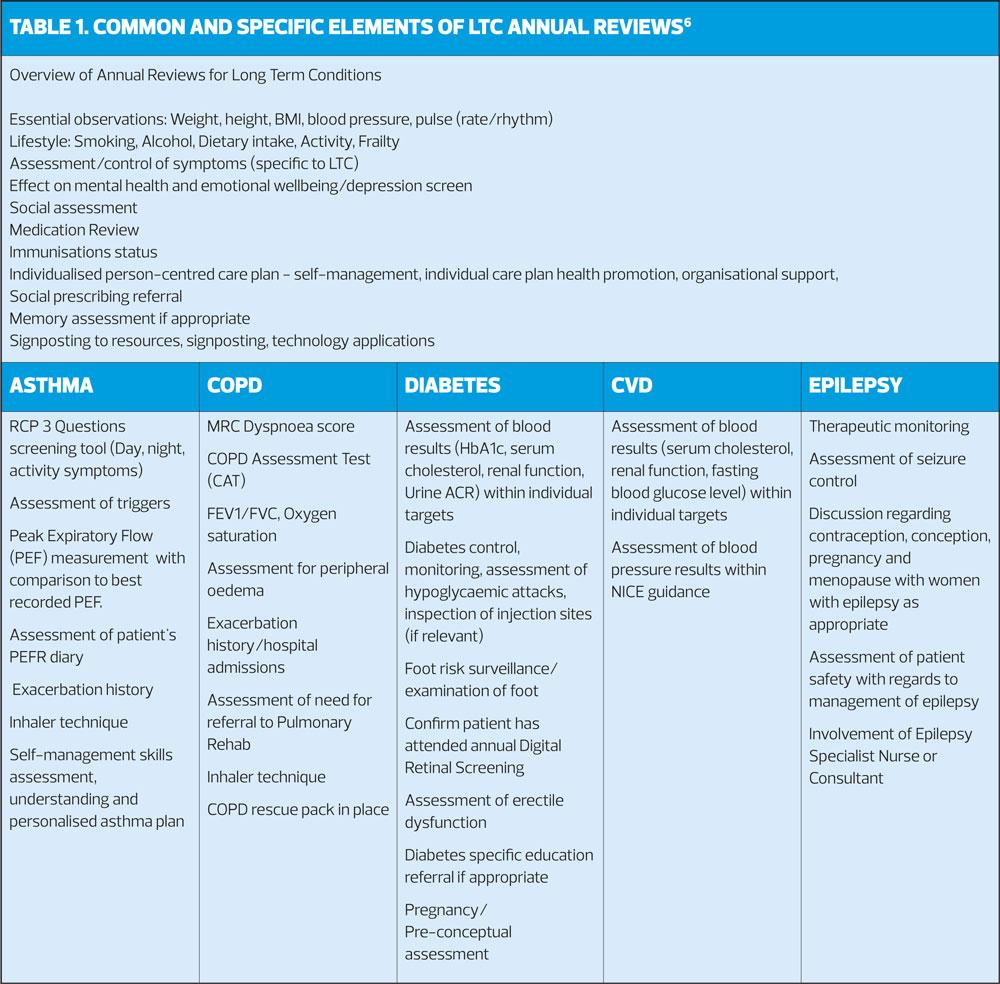

There are elements that are central to all LTC annual reviews, whether it is the young active sports teacher with well-managed and well-controlled asthma, or the older patient who struggles significantly on a daily basis with their heart failure, rheumatoid arthritis and COPD. Fundamental assessments determine how well the patient is managing their condition, what symptoms they have, how good their control is, what support they have in place, which therapies form part of their treatment, and what impact their conditions have on their quality of life and their physical and mental wellbeing. It’s an opportunity too to ensure that the patient is up to date with vaccinations such as influenza, pneumonia and shingles where appropriate. It certainly makes sense that patients who have more than one long term condition have extended reviews to take into account their multimorbidity, rather than having separate appointments for each of the ‘disease areas’, to at least minimise the number of visits to the surgery. In practice, however, this may prove more challenging, depending on the specialities and skill mix of the Nursing Team and the administrative systems in place.

HOLISTIC APPROACH

Getting an impression of a patient’s general wellbeing is a key part of the understanding how their LTCs affect them. Observing a patient walk into a room can give an indication of their physical and mental health. Does the patient rely on walking aids to get into the room? Are they stopping for breath every few paces? What is their general demeanour – do they have a flat affect, avoid eye contact, or do they display physical attributes of anxiety? Furthermore, exploring a patient’s social situation can reveal how much an LTC is affecting their lives. Does their condition have little impact on them; do they have an active and full social life and demonstrate good control of their condition? Or are they essentially housebound, the only social interaction being the meals on wheels service once a week? Are they too breathless or in too much pain to even walk to the front door at times? Clearly these are extremes, but assessment needs to encompass the overall health of the person sitting in front of you and requires you to delve deeper into how that condition is actually affecting them day-by-day.

BASELINE ASSESSMENT

Clinical assessments of blood pressure, pulse, weight, waist measurement, and BMI apply to many annual reviews. You could argue that a blood pressure check isn’t absolutely necessary with an asthma review but it is surely good practice to do so. For example, it could be an opportunity missed if you fail to pick up previously undiagnosed hypertension. Patients who require blood tests as part of their annual reviews should have these taken in advance so that the results are available at the appointment to monitor the specific condition and, for example, determine renal and hepatic function that may be affected by the disease and/or medical treatment.

LIFESTYLE ASSESSMENTS

Fundamental to all annual reviews is an assessment of lifestyle factors. The impact of healthy or poor lifestyles can benefit or hamper physical and mental health and wellbeing respectively. Specifically, with any LTC, GPNs need to determine the following behaviours to enable the patient to plan lifestyle goals to improve their quality of life:

Smoking status

- Review the patient’s own smoking habits and/or exposure to passive smoking

- Use of electronic cigarettes

- Are they amenable to change at this moment in time?

- Do they truly understand and take responsibility for the impact their smoking has on their health?

Alcohol intake

- Use questionnaires such as AUDIT-PC assessment tool to determine drinking habits

- For patients with a higher risk drinking score, use the full AUDIT alcohol harm assessment tool

- Is the patient aware of the ‘low risk’ drinking guidelines and what that entails?7

Exercise and activity

- Consider sending out a questionnaire such as the GPPAQ (General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire) with the Annual Review invitation for patients to complete in advance8

- Assess activity levels in line with NHS Live Well guidance9

- Determine what patients are capable of achieving within the constraints of their LTC.

Dietary habits

- Question the patient on their dietary intake and their understanding of a healthy diet

- Assess the patient’s attitude to food, and cultural considerations

- Discuss the impact of dietary intake on wellbeing

- Use behaviour change interventions such as ‘Let’s Talk about Weight - Ask, Assist, Advise’.10

Following on from the lifestyle assessment of the annual review, it is beyond doubt that making behaviour changes can reap positive rewards. For example, lifestyle improvements can reduce the need for antihypertensive treatments. Dietary improvements and increased activity can prevent the need for escalating diabetes medication as a result of weight loss and the beneficial effect this has on insulin resistance. Improving sleep and reducing stress through mindfulness may improve asthma control, and hence medical management, if stress is a trigger. Discussion of lifestyle changes are therefore a fundamental part of our LTCs reviews – even small changes can make a big difference, and although we do not always have the luxury of time on our side we can at least try a very brief intervention technique to ‘set the seed’.11 Ask the patient what they think they can do to instigate change together with offering simple suggestions and tips, signposting to information, providing resources, sharing local knowledge and recommending apps to improve lifestyle choices.

POLYPHARMACY

Many patients with one or more LTC are on a cocktail of medication as part of the management of their conditions. The use of multiple drugs strikes a fine balance between providing the optimum control of a disease and the over-use and reliance on medications which have the potential for harm.12 We know the risk of harm increases the greater the number of medications taken, but the overall benefit of each medication is also reduced – known as the ‘law of diminishing returns’.

Clearly medicines are vital as part of the management of LTCs – you have a heart attack and, bang, you’re discharged with a party-pack of medicinal products including a statin, beta-blocker, ACE inhibitor and anti platelet therapy – all evidence based, NICE-recommended drug treatments, to reduce the risks of morbidity and mortality. But we should also take into account the impact of drug treatment on patients with many co-morbidities, frail patients, those with an increased risk of adverse drug reactions and those patients who, quite simply, find their prescribed regime unacceptable.

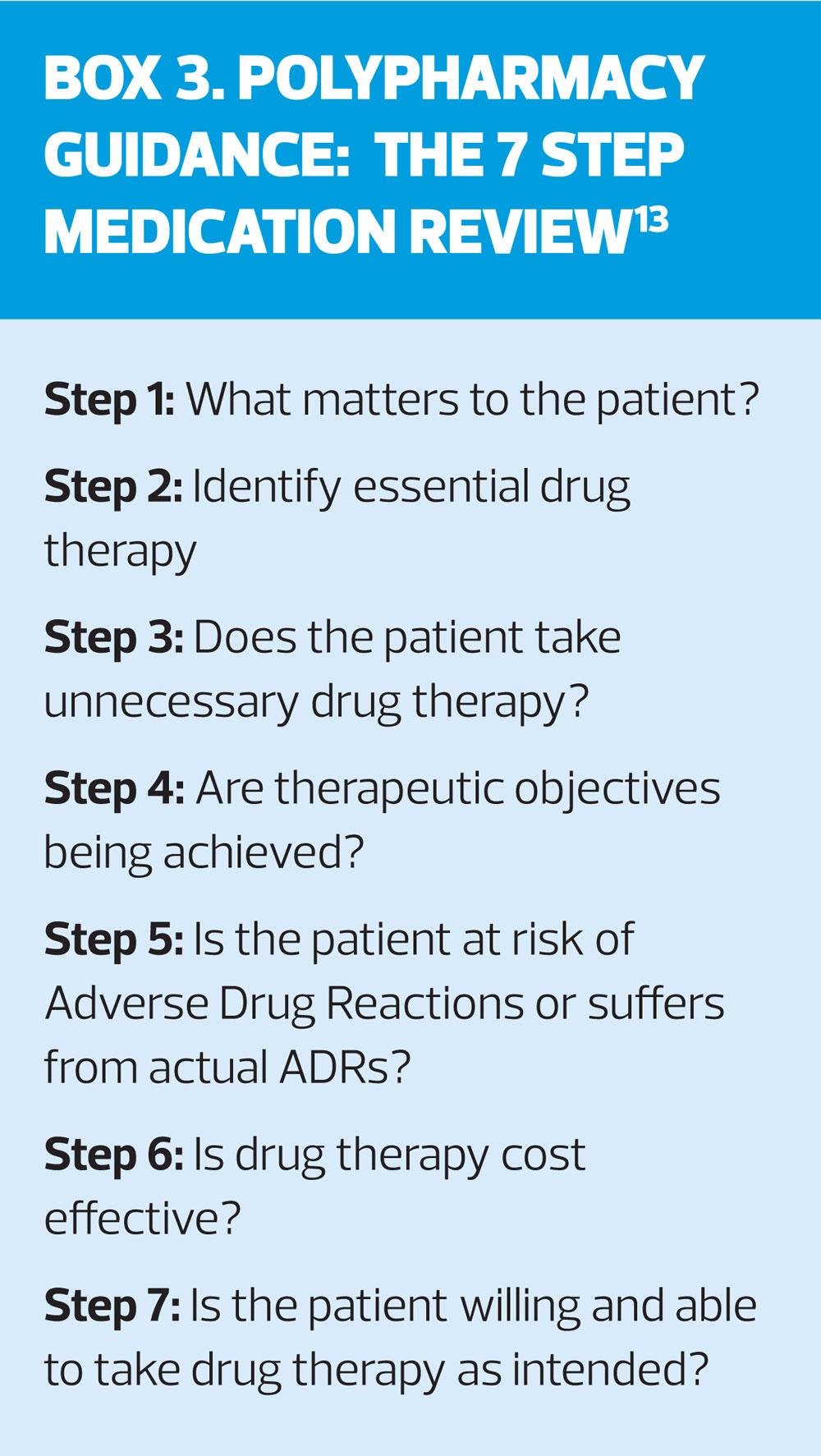

Medication review

An essential element to the annual review of LTCs, therefore, is that we spend time with the patient to discuss their medications together. Patients appreciate time spent going through their often complex regimes and there may be medication which can be stopped or reduced as well as considerations given to alternative management. How many times have you discovered that a patient has started a treatment that should have been stopped, changed or at the very least monitored? The '7 step' process recommended by the Scottish Government Polypharmacy Model of Care Group (2018) is an extremely useful template for conducting a medication review (Box 3)13. Establishing a patient’s beliefs, knowledge and understanding of their condition and its management is paramount. It is important to consider the practicalities involved in taking medication and whether there are any misconceptions about their treatments that need clarification. It may be that we need to provide more comprehensible information in terms of larger print, pictorial symbols or information in another language. There will be some patients who read and inwardly digest the PIL to the very last full stop, whereas others would prefer to have an abridged, but very clear, version.

There’s a lot to ascertain about how a patient takes their medication. Do they take it as prescribed and at the optimum time? How often do they miss doses? Are there some tablets that get forgotten more often than others (such as an evening dose or once a week medication)? Do they know how to take it correctly? What side-effects do they have? Are they being monitored correctly? Do they have reservations about taking their medications?

Maybe there is a bedside cabinet stashed full of untaken, but repeatedly ordered, tablets. It might be that their inhaler technique isn’t actually benefiting them in any way or they’ve misunderstood how to use it. Do we know if they are taking over-the-counter, herbal medication or traditional remedies which could interact with their prescribed drugs? Are patients aware of the ‘Medicine sick-day rules’ and temporarily stopping certain medications which may cause dehydration during periods of illness?14 Do they have impaired cognition?

Taking medications for LTCs can be a ‘trade-off’ – on one hand there is the control of symptoms, on the other there are side-effects which can have an impact to a good, bad or ugly degree. For example, an elderly patient feels more tired since starting his beta blockers but is quite happy to have a short rest in the afternoon; a musician finds her inhaled corticosteroid begins to affect her singing voice and asks for advice; a patient with poorly controlled diabetes complains that the genitourinary side-effects of their new SGLT2 inhibitor are intolerable. It’s about discussing together what the side-effects are and if they are acceptable or not. It’s quite likely our gentleman on beta-blockers is happy to continue as he is, our singer may need some advice on inhaler technique, the use of a spacer and advice on mouth rinsing, and our unhappy patient with diabetes is heading for a change of product! But without exploring these issues, we can’t make assumptions.

Non-adherence to medications

The evidence suggests that around 30-50% of medications taken for LTCs are not taken as prescribed.15 Non-adherence to medication is commonplace and for many patients not intentional. Take a one week course of antibiotics, for example. How easy it is to take a dose late, forget one completely, ignore the advice around whether to take it with food or not, and/or stop the course earlier than prescribed? Sound familiar? Extrapolate that to a patient who is on 10-15 different medications every day of their life for their various LTCs and it’s plain to see how adherence to medications isn’t for the faint hearted. The reasons behind patients not taking medications is multifactorial, whether it’s non-intentional or completely intentional, but it is helpful to establish what factors influence this behaviour and how can we help our patients to improve adherence.

MENTAL HEALTH IMPACT/EMOTIONAL WELLBEING WITH LTCs

The burden of LTCs on an individual’s health can seem insurmountable. Some may feel completely in charge of the disease, but for many others the condition can fully envelop their emotional and mental wellbeing. It is no surprise that people who suffer with a long term physical condition are more likely to experience depression and anxiety as our physical and mental wellbeing go hand in glove. Mental health problems are two to three times more likely to occur in people with LTCs compared to the general population and in turn this contributes to poorer health outcomes; patients are less likely to self-manage their conditions and this in turn reduces their quality of life.16 Furthermore, the risk of cognitive decline is increased with CHD and diabetes. Social isolation, loss of self-esteem, discrimination can all compound emotional ill-health further. Integrating mental health assessment and support into our patients’ LTC annual review should be intrinsic. A first step would be asking patients to complete a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2/PHQ-9) to determine a potential risk of depression and a Generalised Anxiety Disorder tool (GAD-2, GAD-7) for patients you suspect may have an anxiety disorder. In recognition of the effects of LTCs on mental health, one of the aims of The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health is to align more closely mental wellbeing therapies with physical health in Primary Care.17 From the GPN perspective, referring patients to local mental health services, such as IAPT, Talking Therapies and CBT, may be appropriate, as well as providing details of local organisations such as Mind or Wellbeing Services. Directing patients to websites and apps for self-help and support may also be beneficial.

SOCIAL PRESCRIBING

The value of social prescribing as an intervention for managing LTCs is well-recognised.18 Living with an LTC can have significant impact on an individual’s emotional wellbeing and can make people feel isolated and lonely as well as causing stress. As well as the physical and emotional impacts of LTCs already described, they can also have financial implications, which may significantly impact on housing, families and relationships. Social Prescribing Link workers can offer a supportive service by finding out what is important to each individual in a social context. They help to make a plan together with the patient to improve their quality of life and wellbeing through accessing local community services. Such support may include counselling, befriending, recommending local groups and activities, specialist services, housing and financial support, volunteering, training and legal support. Pointing patients in the direction of Social Prescribing may pay dividends to the management of their LTC and their daily lives.

CONDITION-SPECIFIC REVIEWS

Clearly there are very specific assessments and management that we need to undertake for individual long term conditions beyond a more generic assessment of health and wellbeing. Table 1 shows elements to the LTC review that are shared by annual reviews and details the specifics of some of the reviews we carry out in primary care. By fine-tuning our reviews we can avoid duplication for our patients who have more than one LTC in an attempt to reduce visit numbers and time, and improve continuity of care.

A PERSON-CENTRED APPROACH

Personalised care and support enables our patients to feel more confident in managing their condition through understanding of the ailment in question. Recognition of factors that lead to improvements, as well as preventing deterioration of their LTC, will impact on the individual’s ability and confidence to cope with and manage their condition. There is much of our annual reviews which apply to all long term conditions and, as much as we are able, within our time constraints in practice, our aim is to co-ordinate the care and support we give our patients to provide a more amalgamated and holistic approach. The idea of the NHS ‘House of Care’ is to do just that in the management of Long Term Conditions – a person-centred approach through partnership with professional healthcare and social support together with community services and resources to enable individuals to self-manage to achieve their goals.19

We may just have just a 20-30 minute window into their condition. Our patients have to live with it every single day.

FURTHER READINGPractice Nurse ‘Guidelines in a Nutshell’ summary of Polypharmacy Guidance, Realistic Prescribing, August 2018 (Online only) Morrow G. Multimorbidity: implications for general practice nurses. Practice Nurse 2018;48(10):12-16Bryant E, Oliver L. The Year of Care - planning together for effective care. Practice Nurse 2016;46(3):36-40

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG56. Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management, September 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56

2. NHS England. Enhancing the Quality of Life for People Living with Long Term Conditions (LTCs). https://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/essential-facts-stats-and-quotes-relating-to-long-term-conditions/:

3. NHS England. Next steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View, March 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEXT-STEPS-ON-THE-NHS-FIVE-YEAR-FORWARD-VIEW.pdf

4. NHS England. The NHS Long Term Plan, January 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/nhs-long-term-plan.pdf

5. Royal College of General Practitioners. RCGP Health Select Committee Inquiry on Management of Long-Term Conditions, 2013. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/rcgp-policy-areas/long-term-conditions.aspx

6. NICE. NICE Quality and Outcomes Framework Indicators, 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/standards-and-indicators/qofindicators

7. Department of Health, Llywodraeth Cymru Welsh Government, Department of Health Northern Ireland, Scottish Government. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Low Risk Drinking Guidelines, August 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545937/UK_CMOs__report.pdf

8. NHS England. General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire, April 2013. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/192450/GPPAQ_-_pdf_version.pdf

9. NHS. Live Well Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/

10. Let’s Talk About Weight: A step-by-step guide to brief interventions with adults for health and care professionals, June 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/620405/weight_management_toolkit_Let_s_talk_about_weight.pdf

11. NICE PH49. Behaviour change: individual approaches, 2014.

12. NICE. Key therapeutic topic KTT18. Multimorbidity and polypharmacy, 2017 (updated March 2019). https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/ktt18

13. Scottish Government Polypharmacy Model of Care Group. Polypharmacy Guidance Realistic Prescribing 3rd Edition, 2018. https://www.therapeutics.scot.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Polypharmacy-Guidance-2018.pdf

14. Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Medicines and dehydration: Patient Information version 2, 2018. https://www.therapeutics.scot.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Polypharmacy-Guidance-2018.pdf

15. NICE CG76. Medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. 2009 (updated 2019). https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG76

16. The King’s Fund Centre for Mental Health. Long Term Conditions and Mental Health: the cost of co-morbidities. February 2012. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/long-term-conditions-mental-health-cost-comorbidities-naylor-feb12.pdf

17. NHS England. Five Year Forward View for Mental Health: One Year On. February 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/fyfv-mh-one-year-on.pdf

18. The King’s Fund. What is Social Prescribing, February 2017. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/social-prescribing

19. NHS England. House of Care – a framework for long term condition care. Accessed 6 April 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical-policy/ltc/house-of-care/