Red eyes: assessment

Simon Hardman Lea

Consultant Ophthalmologist and Clinical Director, Evolutio Care Innovations

Lyn Price

Senior Optometrist and Clinical Lead, Evolutio Care Innovations

Christian Dutton, Professional Services Optometrist & Independent Prescriber.

INTRODUCTION

Patients presenting with eye problems account for up to 1 in 20 of primary care consultations, but most non-ophthalmic clinicians do not have significant knowledge or feel comfortable with their training in ophthalmology. This module provides an overview of the conditions presenting with red eyes.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this module, you should be more familiar with:

- The structures of the eye and why eyes go red

- Common conditions affecting the eyelids and conjunctiva

- Conditions warranting specialist referral

- A simple, practical approach to assessing a patient presenting with red eyes

- What to do in the case of young children with red or sticky eyes

This resource is provided at an intermediate level. Read the accompanying article, which provides further detail and management options, before answering the self-assessment questions, and reflecting on what you have learned.

Complete the resource to obtain a certificate to include in your revalidation portfolio. You should record the time spent on this resource in your CPD log.

Contents

Patients presenting with eye problems account for up to 1 in 20 of primary care consultations,1-3 but most non-ophthalmic clinicians do not have significant knowledge or feel comfortable with their training in ophthalmology.4

In general, eye problems divide into visual issues or sore/painful eyes: in the UK, patients with visual problems often seek help from their optometrist rather than their GP or general practice nurse. This article therefore looks at a practical approach to the assessment of patients presenting with painful red eyes. It is aimed at the non-specialist clinician and assumes minimal prior knowledge of eye structure or specific ocular disease. It aims to work from first principles through to management, with consideration of possible diagnoses.

FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES: WHY DO EYES GO RED?

Most accounts of painful red eyes delve straight into diagnoses or specific conditions, but for a generalist clinician, it is more useful to take an approach that builds up from a basic understanding, as follows.

Only eye structures with prominent blood vessels can show red discolouration as those blood vessels get inflamed.

The main eye structures that can do this are the lids and the conjunctiva (the transparent membrane that lines the inside of the lids and covers the surface of the eyeball itself.) The episclera (the thin layer of soft white tissue between the conjunctiva and the eyeball) can also go red, but to a lesser extent.

Lids can be inflamed by:

- Acute formation of cysts in the deeper tissues. Very common.

- Localised bacterial infections of the eyelash follicles (stye). Very common.

- Spreading infection of soft tissues (cellulitis). Rare but serious.

- Malfunction of the oil glands (the Meibomian glands) in the lids (blepharitis). Extremely common.

The conjunctiva can be inflamed by many pathologies. It is common – but wrong – to describe all eyes presenting with a red conjunctiva as ‘conjunctivitis’. The risk is that ‘conjunctivitis’ is always taken to imply an infectious cause, but there actually are many causes for the conjunctiva to become inflamed.5,6

Causes for conjunctival inflammation fall into two main groups.

Processes directly affecting the conjunctiva itself:

- Mechanical trauma from the eyelids turning in (entropion) or out (ectropion)

- Infection, which is almost always viral. (Despite most textbooks accounts, bacterial infection is rare.)

- Allergy, including atopy

- Chemical injury, including eye drops and their preservatives

Pathology affecting other adjacent ocular structures:

- Infection, surface breakdown or trauma to the cornea – the transparent dome over the front of the eye – (keratitis)

- Inflammation inside the front of the eye (iritis)

- Suddenly raised pressure in the eye (acute glaucoma)

- Inflammation of the white of the eyeball itself – (scleritis or episcleritis)

SPECIFIC CONDITIONS

Lid cyst

Both upper and lower eyelids have a row of simple, oil glands (the Meibomian glands) deep in their tissue. These commonly get blocked at their outlet on the eyelid edge, and then oily material quickly builds up, distending the gland into a round cyst (Figure 1). In the first few days when the cyst is developing, the lid is quite painful and inflamed – a fact often encountered clinically but rarely mentioned in textbooks. This is the commonest cause of a tender, swollen eyelid, although the eye itself remains white and quiet. After a few days, the pain settles leaving an obvious lump in the lid. At least half of these will settle over the course of 12 weeks.

Management: in the acute, painful phase there is no direct treatment apart from using warm massage twice daily (the handle of a teaspoon heated in warm water is the right size to apply heat over the cyst.)

If a cyst then persists for more than 12 weeks, it may need referring for treatment by surgical incision.

Lid cellulitis

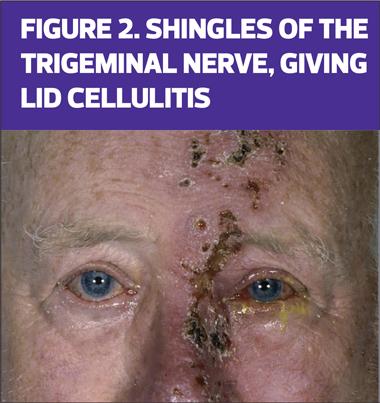

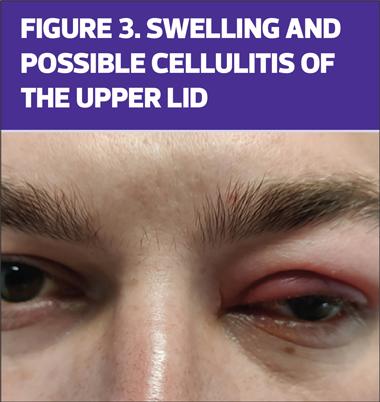

Spreading infections in the eyelid (cellulitis) are much rarer, but much more serious. They can be due to virus, such as Herpes zoster (shingles – see Figure 2), or bacteria spreading from the paranasal sinuses. Compared with early, inflamed lid cysts, cellulitis produces more swelling, (Figure 3), often of both upper and lower lids, and often causes the eye to be red also. In a matter of hours, it can affect eye movements (producing double vision) and sight itself.

Management: suspected lid cellulitis (often as part of orbital cellulitis) is one of the small number of true eye emergencies, threatening both vision and life. It must be referred to specialists immediately.

Lid malpositions

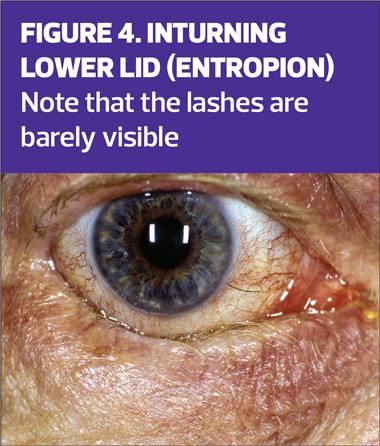

These are often seen in older patients and cause red eyes. The lower lid can turn in and rub against the eye (entropion, Figure 4) or can turn out and expose the inner surface of the lid, which goes red (ectropion, Figure 5) while the eyeball itself is white.

Management: simple lubrication with artificial tears can help. Inturning lids need referring to a specialist for treatment (usually with either Botox injections or surgery).

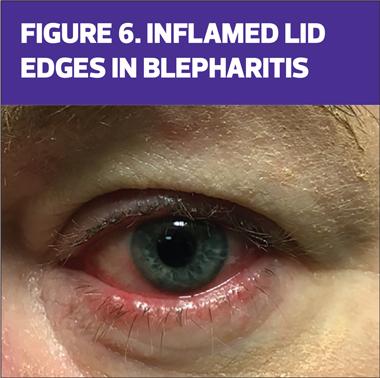

Blepharitis

Blepharitis (Figure 6), or inflammation of the eyelids, is incredibly common at all ages, especially if the patient suffers from facial acne rosacea. Most cases of recurrent red eyes are caused by blepharitis.

It is not usually caused by infection, but by malfunction of the skin on the edge of the eyelid. Accumulation of inflammatory chemicals on the lid edge irritates the conjunctiva, producing a red eye, as well as red lid edges.

Management: In mild cases, nightly lid cleaning is very effective, using a cotton bud soaked in warm boiled water with a small amount of salt added (1/4 teaspoon per mug of water) to wipe along the rim of the eyelids – top and bottom. More painful cases will need referral for specialist management, usually with combined steroid and antibiotic drops.

Viral conjunctivitis

The majority of sudden onset redness of the conjunctiva is caused by viral infection (Figure 7). Typically, this causes sandy, gritty eyes bilaterally, with normal lids and vision. Because all inflamed surfaces in the body exude plasma, there will often be discharge, and this is not helpful in distinguishing viral from bacterial infections. Recurrent viral conjunctivitis is rare.

Rarely, bacterial conjunctivitis is encountered, usually caused by those bacteria that act like viruses and actually invade cells, such as Neisseria gonorrhoea or Streptococcus pneumonia.7 Similarly, chlamydia can cause conjunctival inflammation as it also invades cells.

Management: unless vision is affected, there is no specific treatment for viral conjunctivitis: the condition will settle within 10–14 days. Antibiotic drops are not indicated8,9 and are significantly overused. The occasional case of bacterial conjunctivitis settles with 5 days and does not require treatment either.

The only exceptions to this are either where the vision is affected, or if there is a possibility of gonococcal or chlamydial infection. In either of these cases, patients must be referred for specialist management.

NB. The topical antibiotic most commonly prescribed in the UK – chloramphenicol – has no role in the treatment of viral conjunctivitis and has little effect on the bacteria that do cause bacterial conjunctivitis.8,9

Sub-conjunctival haemorrhage

These bright red haemorrhages are common, usually asymptomatic and often only noticed by the patient when looking in the mirror. They are the equivalent of a spontaneous bruise in the skin but happen more often as the conjunctiva is very loose tissue, and resolve in a matter of days.

Management: check for blood pressure elevation, as this can be a cause. If uncomfortable, lubricating artificial tear drops can be bought over the counter in pharmacies.

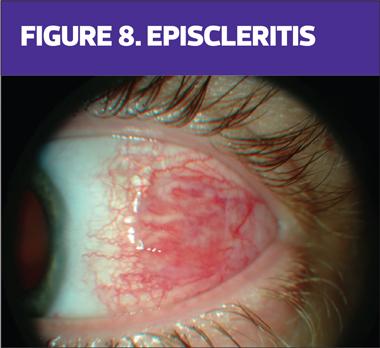

Episcleritis

The episclera is the soft white packing tissue between the transparent conjunctiva and the tough, connective tissue sclera that forms the outer coating of the eyeball itself. Inflammation of the episclera (Figure 8) is common and usually involves a small sector of the ocular surface only, causing mild foreign body sensation and itch. Scleritis is rare, again often sectoral and always extremely painful – similar to gout in intensity.

Management: episcleritis normally responds well to mild topical steroid for a few days. The much more painful scleritis needs intensive topical steroid, plus systemic immunosuppression in many cases. Scleritis should therefore be referred urgently for specialist management

Keratitis

Any inflammation affecting the cornea – the transparent dome covering the iris – is termed keratitis (Figure 9). The commonest cause is infection from viruses, especially adenoviruses and Herpes simplex, but bacterial infections are also seen especially in contact lens wearers. Keratitis causes unilateral pain, photophobia and often a degree of reduced vision.

Management: Because the cornea should normally be clear, any opacity in the cornea of a red eye should be suspected as keratitis and referred immediately for specialist management.

NB. Dry eyes are incredibly common. Mild dry eye often causes no surface signs at all. Moderate to severe dry eye often causes patchy corneal surface breakdown, but clinically it is rare for dry eyes to go red. (For unknown reasons, in this condition, the conjunctiva does not seem to get inflamed, even when corneal involvement causes severe pain – which means the patient’s suffering does not even elicit sympathy from onlookers!)

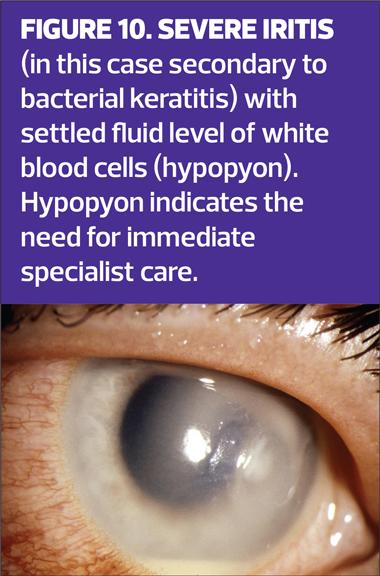

Iritis

Inflammation inside the eye usually arises in the iris, as part of an auto-immune process. It is often therefore associated with more generalised diseases, especially HLA B27 positive conditions like ankylosing spondylitis. Usually unilateral, the eye is red, photophobic and vision may be a little reduced. The pupil may be an irregular shape because of being inflamed. If inflammation is severe, the white blood cells inside the eye may be so copious that they fall into a white fluid layer in front of the bottom of the iris, called a hypopyon (Figure 10).

Management: Any patient with possible iritis should be referred urgently for specialist management, usually with topical steroids.

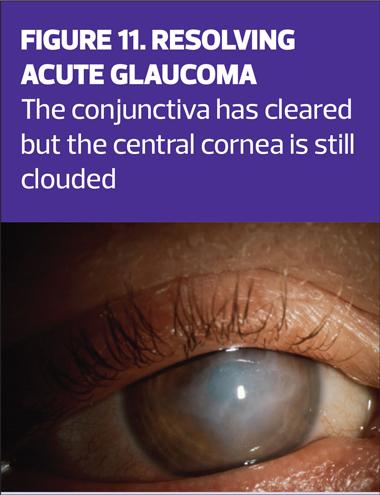

Acute rise in eye pressure (acute glaucoma)

Occasionally, the normal pressure inside the eyeball can rise very suddenly. The eye goes red, with photophobia, reduced vision and a cloudy cornea (Figure 11). The patient usually feels acutely unwell, with headache and profound nausea, often with vomiting. It is actually easy to gauge if the pressure in an eye is very high by feeling the eye with two fingers through the closed upper lid and then comparing with the normal fellow eye.

Management: refer immediately for specialist management. Consider giving analgesia and anti-emetic medication meanwhile – this often needs to be via intramuscular injection because of the associated vomiting.

PRACTICAL APPROACH TO A PATIENT PRESENTING WITH RED EYES

If the conjunctiva and lids can be inflamed for so many reasons, how can we sort out a logical approach to red eyes? There are many algorithms, designed to help with this process, some more complex than others. For the non-specialist, however, the simpler the approach the better.5,10 A reduced 4-point process has been assessed and shown to improve the appropriate management of patients,11 but this can be improved further, still following a simple and quick framework.

This approach requires noting the answers to four specific questions, and then recording two simple observations.

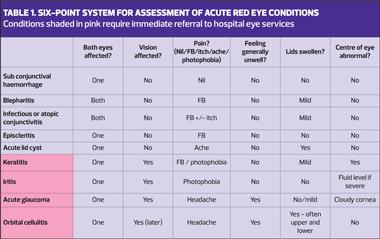

Question 1: Are both eyes involved, or only one?

Question 2: Is the vision affected? (This may need prompting the patient to cover one eye, then the other.)

Question 3: What does it feel like? (The choices are: normal/ foreign body sensation/itch/ache/light sensitive [photophobia])

Question 4: Does the patient generally feel well?

Observation 1: Are the lids normal? Is there any swelling, or turning in/out?

Observation 2: Does the front of the eye look normal? Apart from the redness, does the cornea look clear or is there any opaque area? Is there a fluid level inside the eye, in front of the iris?

The answers to these six points can then be checked against Table 1 (below), which shows the most likely diagnosis.

SPECIAL CASE: RED EYES IN YOUNG CHILDREN

Babies under the age of one month who have red, sticky eyes must be referred immediately for specialist care. The risk here is that they may have developed conjunctivitis from Chlamydia, Gonococcus or Herpes simplex 2 generalised infection acquired from the maternal birth canal. Prompt intervention with systemic antibiotics/antivirals is generally needed for both infant and mother.

Older infants (to the age of 18 months) often present with sticky eyes that are not red, and do not seem to be troubling the child in spite of profound discharge. This is not due to active infection, but to delayed development of the tear drainage passages through the nose, which allows overgrowth of bacteria in the tear drains. Providing the eyes are not red, the recommended management is not to prescribe antibiotics, but to keep the eye clean only by wiping with cotton pads moistened with boiled water. If the problem persists past the age of one year, referral for specialist management is then indicated.12

REFERENCES

1. Kilduff C, Lois C. Red eyes and red-flags: improving ophthalmic assessment and referral in primary care. BMJ Open Quality

2016;5:u211608.w4680. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u211608.w4680

2. Dart JKG. Eye disease at a community health centre. BMJ 1986;293:1477–1480.

3. Shields T, Sloane PD. A comparison of eye problems in primary care and ophthalmology practices. Fam Med 1991;23(7):544-6.

4. Welch S, Eckstein M. Ophthalmology teaching in the medical schools: a survey in the UK. Br J Ophthalmol 2011;95:748-9

5. Lansingh VC, Eckert KA, Ramos SV, Star EML. From Acute Disease to Red Flags: A Review of the Diverse Spectrum of Red Eye Encountered in the Primary Care Setting. Prim Health Care 2018;8:316-325.

6. Sheldrick J, Wilson A, Vernon S, Sheldrick C. Management of ophthalmic disease in general practice. Brit J Gen Pract 1993;43(376):459-62

7. Subramanian K, Henriques-Normark B, Normark S. Emerging concepts in the pathogenesis of the Streptococcus pneumoniae: From nasopharyngeal colonizer to intracellular pathogen. Cell Microbiol 2019;21(11):344-350

8. Frost HM, Sebastian T, Durfee J, Jenkins TC. Ophthalmic antibiotic use for acute infectious conjunctivitis in children. J AAPOS 2021;25(6):350.

9. American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Cornea/External Diseases Committee. San Francisco, CA. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2018;95-169.

10. Timlin H, Butler L, Wright M. The accuracy of the Edinburgh Red Eye Diagnostic Algorithm. Eye 2015;29:619–624

11.Teo MAL. Improving acute eye consultations in general practice: a practical approach. BMJ Open Quality 2014;3:u206617.w2852. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u206617.w2852

12. Vagge A, Ferro Desideri L, Nucci P, et al. Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction (CNLDO): A Review. Diseases. 2018 Oct 22;6(4):96-101

Related modules

View all Modules