New guideline transforms approach to therapy in T2D

American Diabetes Association, European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD), 2018

American Diabetes Association, European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD), 2018

New consensus guidance from the American Diabetes Association and European Association for the Study of Diabetes offers a dramatic shake-up of the conventional order of glucose lowering drugs, with newer agents given more prominent ‘ranking’.

The latest consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD)on the management of hyperglycaemina in type 2 diabetes (T2D) puts new emphasis on drugs that have benefits beyond their ability to lower blood glucose.

Patients with clinical cardiovascular disease should be offered glucose-lowering medications with proven cardiovascular benefits, and patients with chronic kidney disease should be offered a treatment with proven renal benefits.

Metformin remains the first-line drug of choice but sulfonylureas (SUs) and thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are only recommended if cost is the most pressing consideration, and other drugs are recommended in preference to SU at first intensification after metformin.

OVERARCHING GOALS

The goals of treatment for T2D are to prevent or delay complications and to maintain quality of life. This requires control of glycaemia and comprehensive cardiovascular risk factor management, regular follow-up and a patient-centred approach to encourage patient engagement in self-care. Lifestyle management, including physical activity, weight loss, smoking cessation and psychological support are fundamental. This will be covered in more detail below.

Good glycaemic control produces substantial and lasting reductions in both the onset and the progression of microvascular complications, although the impact on macrovascular complications is less certain. Because the benefits of intensive glucose control emerge slowly, while the harms can be immediate, people with longer life expectancy have more to gain from intensive glycaemic control. Treatment targets should therefore be individualised, taking into account patient preferences and goals, risk of adverse effects of therapy such as hypoglycaemia and weight gain, and patient characteristics such as frailty and comorbidities.

SELF-MANAGEMENT

Diabetes self- management education and support (DSMES) is a key intervention for all people with T2D, and should be available on an ongoing basis – but critical times when it should be provided include at diagnosis, annually, when complications arise and during transitions in life and care. DSMES can promote medication adherence, healthy eating and physical activity. It is cost-effective, and can improve outcomes and glycaemic control and reduce hospital admissions and all-cause mortality.

Recommendation

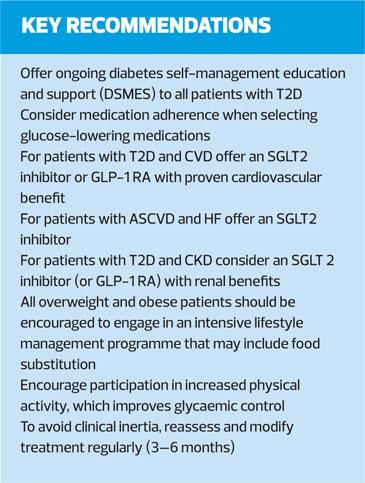

All people with type 2 diabetes should be offered access to ongoing diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES)

ADHERENCE

Suboptimal adherence and poor persistence to therapy affect almost half of people with diabetes, leading to suboptimal glycaemic and CVD risk factor control, and increase the risk complications, mortality, admissions and healthcare costs.

Multiple factors contribute to inconsistent medication use and treatment discontinuation, including patient-perceived lack of efficacy, fear of hypoglycaemia, and adverse effects. Adherence varies across medication classes – another factor to consider.

Recommendation

Facilitating medication adherence should be specifically considered when selecting glucose-lowering medications

CLINICAL INERTIA

Clinical inertia means failure to intensify therapy when treatment targets are not met. Avoiding inertia help to improve glycaemic control. Having a multidisciplinary team that includes nurse practitioners or pharmacists may help to reduce inertia, as does a coordinated chronic care model, while a fragmented healthcare system may contribute to inertia.

Recommendation

To avoid clinical inertia, reassess and modify treatment regularly (3–6 months)

SELECTING THERAPY

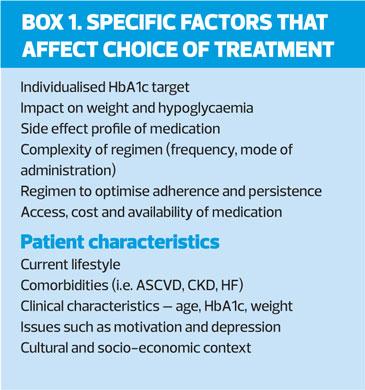

The expanding number of glucose-lowering treatments and increasing information about their benefits and risks provides more options – but can complicate decision-making. ADA/EASD recommends a number of considerations when selecting the most appropriate medication, including the presence of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), presence or risk of heart failure (HF), and renal disease. In addition to CVD, the guideline recommends early consideration of weight, hypoglycaemic risk, treatment cost and other patient-related factors (Box 1).

In previous ADA/EASD consensus statements, efficacy in reducing hyperglycaemia, along with tolerability and safety were considered the primary factors in the selection of glucose-lowering drugs. The new consensus approach takes into account new evidence for the benefit of some drugs – specific SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists to reduce mortality, heart failure and progression of renal disease in the setting of established CVD[/italics], and their use is considered compelling in this patient group.

In addition to improving cardiovascular outcomes, some of these agents have shown secondary improvements in heart failure (HF) and progression of renal disease,

So the guideline recommends that prescribers consider a history of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), HF and CKD, very early in the process of treatment selection. Together, these conditions affect 15-25% of the population with T2D.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

The evidence for cardiovascular benefits comes from large cardiovascular outcomes trials (CVOTs) with varying results for individual drugs, so it is not clear whether there are true class effects, or whether there are real differences between medications within a class. All the trials included subjects with established CVD (myocardial infarction [MI], stroke, revascularisation procedure), while some also included related atherosclerotic conditions such as angina or heart failure. Most trials also included a ‘risk factor only’ group. The trials were designed to demonstrate cardiovascular safety, but several showed ASCVD outcome benefits.

GLP-1 receptor agonists

Among the GLP-1 RAs, the strongest evidence for cardiovascular benefit was for liraglutide, which showed an absolute risk reduction (ARR) of 1.9% for cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI, and non-fatal stroke (major adverse cardiac events [MACE]) over 3.8 years. Semglutide reduced MACE by 2.3% over 2.1 with most of the reduction attributable to the rate of stroke, rather than CVD death. Exenatide extended-release was shown to be safe, but did not reach the threshold for superiority versus placebo, with an ARR of 0.8%. Lixisenatide, a short-acting GLP-1 did not demonstrate CVD benefit or harm in a trial of patients recruited within 180 days of an acute coronary syndrome admission.

In the GLP-1 studies there was no significant effect on hospitalisation for HF.

SGLT2 inhibitors

Among the SGLT2 inhibitors studied up to the cut off point for inclusion this update – 28 February 2018 – it appears that among patients with established CVD there is likely cardiovascular benefit.* (*A number of cardiovascular outcome trials among SGLT2 inhibitors, including further analyses of data from the CANVAS programme for canagliflozin, and the DECLARE trial with dapagliflozin, have been published since the cut off point (28 February 2018)). The ARR for cardiovascular death with empagliflozin was 2.6%. In the CANVAS programme, where 66% of patients had a history of CVD, canagliflozin showed a reduction in the primary composite endpoint of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death (26.9 vs 31.5 participants per patient-year compared with placebo). Though there was a trend towards benefit for cardiovascular death, the difference from placebo was not statistically significant.

In both the EMPA-REG and CANVAS CVOTs, there was a clinically and statistically significant reduction in hospitalisation for HF with the SGLT2 inhibitor compared with placebo.

DPP-4 inhibitors

CVOTs in DPP-4 inhibitors have demonstrated cardiovascular safety but not cardiovascular benefits. Reductions in rates of hospitalisation for HF with DPP-4 inhibitors were variable between agents, with the rate for sitagliptin the same as for placebo; with alogliptin there was a reduction in hospitalisations but this did not reach statistical significance versus placebo; and for saxagliptin, the rate was higher. [Both alogliptin and saxagliptin are subject to FDA warnings against use in HF.]

Recommendations

Patients with clinical CVD not meeting individualised glycaemic targets while treated with metformin (or in whom metformin is not tolerated or contraindicated) should have an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 RA with proven CV risk reduction benefit added to their treatment programme. Among patients with ASCVD for whom HF is a concern, an SGLT2 inhibitor is recommended.

Dose adjustment to background medication may be required to avoid hypoglycaemia when adding a new agent to a regimen containing insulin or a sulfonylurea.

Full efforts to achieve glycaemic and blood pressure targets and to follow guidelines for lipid management, antiplatelet and antithrombotic therapy, and smoking cessation should continue after the addition of an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 RA.

KIDNEY DISEASE

Patients with T2D and kidney disease are at increased risk for cardiovascular events.

Substantial numbers of patients with an eGFR of 30-60ml/min/1.73m2 were included in the CVOTs for SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs. Even among these patients there were reductions in the primary ASCVD outcomes, and most of these trials reported benefits in renal endpoints. Renal benefits were most notable and consistent for SGLT2 inhibitors. Empagliflozin reported an ARR of 6.1% for the composite outcome of new or worsening nephopathy, doubling of serum creatinine and end stage renal disease (ERSD) or renal death. Canagliflozin reported regression of albuminuria and a 40% reduction in risk in the composite outcome of eGFR, ESRD or renal death.

In the GLP-1 RA CVOTs, liraglutide was associated with an ARR of 1.5% for new or worsening nephropathy. Most of the benefit derived from reductions in progression of albuminuria, whereas there was little benefit in other components of the composite renal endpoint – doubling of serum creatinine, ESRD or renal death.

In the DPP-4 inhibitor CVOTs, this class was shown to be safe from a renal perspective, with modest reductions in albuminuria.

Recommendation

For patients with T2D and CKD, with or without CVD, consider an SGLT2 inhibitor shown to reduce CKD progression, or if contraindicated or not preferred, a GLP-1 with evidence of renal benefit.

LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT

Lifestyle interventions including education and support to help patients adopt health eating patterns and increase physical activity are recommended first line from the time of diagnosis and as co-therapy for patients who need glucose-lowering treatment. Lifestyle management should be part of ongoing care of people with T2D.

No specific dietary advice is recommended but ADA/EASD points out that the ‘Mediterranean’ eating pattern reduced HbA1c more than control diets. Low carbohydrate, low glycaemic index and high protein diets, and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet all improve glycaemic control.

Very low calorie diets involving meal replacement formula diets with intensive counselling followed by gradual reintroduction of food resulted in high rates of diabetes remission.

Aerobic exercise, resistance training and the combination of the two are effective in reducing HbA1c by about 6.6mmol/mol (0.6%). Leisure activities such as walking, swimming, gardening, jogging, tai chi and yoga, can also significantly reduce HbA1c.

Recommendation

All overweight and obese patients should be encouraged to engage in an intensive lifestyle management programme that may include food substitution; increased physical activity improves glycaemic control and should be encouraged.

OBESITY

A number of guidelines recommend weight loss medications as an addition to intensive lifestyle management for obese patients, particularly if they have diabetes but others do not. Several medications or combinations are approved in the US and Europe for weight loss, and have been found to improve glucose control in people with diabetes. One, liraglutide (as Saxenda), is approved for the treatment of obesity at a higher dose than used for glycaemic control. However, cost, side effects and modest efficacy limit the role of pharmacotherapy in long-term weight management.

Recommendations

Metabolic surgery is a recommended treatment option for adults with T2D and a BMI of ≥40 kg/m2 (37.5 kg/m2 in patients with Asian ancestry) or with a BMI of 35–39.9 kg/m2 (32.5–37.4 kg/m2) who do not achieve lasting weight loss and improvement in co-morbidities with reasonable non-surgical methods

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER: STRATEGIES FOR IMPLEMENTATION

For increasing numbers of patients, presence of specific co-morbidities (ASCVD,HF, CKD, obesity), safety concerns (e.g. hypoglycaemia) or cost of medication dictate the specific approach to the choice of medication.

For patients not reaching target HbA1c it is important to re-emphasise lifestyle measures, address adherence and ensure timely follow-up.

Initial monotherapy

Metformin is still the preferred option for initial glucose-lowering medication and should be added to lifestyle measures in newly diagnosed patients. This recommendation is based on the efficacy, safety, tolerability, low cost and extensive clinical experience with this medication.

Stepwise addition of glucose lowering medication is generally preferred to initial combination therapy. There is little evidence that initial combination therapy is superior to the sequential addition of medications for maintain glycaemic control or slowing the progression of diabetes, even though the former may result in greater initial reduction of HbA1c. However, initial combination therapy can be considered for patients presenting with HbA1c levels exceeding 17mmol/mol above their target.

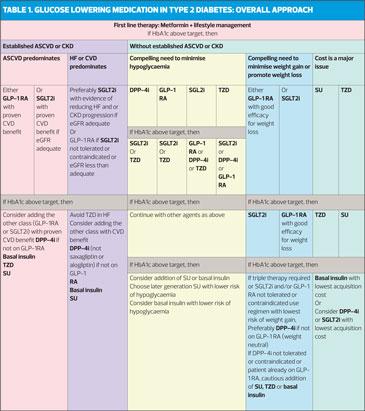

Choice of medication after metformin

The selection of medication to be added to medication should be based on patient preference and clinical characteristics – presence of ASCVD, HF, CKD; the risk of adverse effects, e.g. hypoglycaemia and weight gain; safety, tolerability and cost. See Table 1.

Sulfonylureas and insulin are associated with an increased risk of hypoglycaemia and would not be preferred for patients in whom this is a concern. Furthermore, hypoglycaemia is distressing and so may reduce treatment adherence.

For patients prioritising weight loss or weight maintenance, important considerations include the weight reduction associated with SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, the weight neutrality of DPP-4 inhibitors, and the weight gain associated with sulfonylureas, basal insulin and TZDs.

An important consideration for society in general is the cost of medications; sulfonylureas, pioglitazone and recombinant human insulins are relatively inexpensive, although their cost may vary across regions. Short-term acquisition costs, longer-term treatment cost and cost-effectiveness should be considered in clinical decision making when data are available.

The lack of a substantial response to one or more non-insulin therapies should raise the issue of adherence and, in those with weight loss, the possibility that the patient has autoimmune (type 1) or pancreatogenic diabetes. However, it is common in people with long-standing diabetes to require more than two glucose-lowering agents, often including insulin. Compared with the knowledge base guiding dual therapy of T2D, there is less evidence guiding these choices. In general, intensification of treatment beyond two medications follows the same general principles as the addition of a second medication, with the assumption that the efficacy of third and fourth medications will be generally less than expected [if used in mono- or dual therapy]. No specific combination has demonstrated superiority except for those that include insulin and GLP-1 receptor agonists that have broad ranges of glycaemic efficacy. As more medications are added, there is an increased risk of adverse effects. It is important to consider medication interactions and whether regimen complexity may become an obstacle to adherence. Advice on action regarding oral therapy following initiation of injectable medication is shown in Figure 1.

CONCLUSION

Despite over 200 years of research on lifestyle management of diabetes and more than 50 years of comparative-effectiveness research in diabetes, innumerable unanswered questions regarding the management of type 2 diabetes remain.

For example, does metformin provide cardiovascular benefit in patients with type 2 diabetes early in the natural history of diabetes, as suggested by the UKPDS study? Is metformin’s role as first-line medication management truly evidence-based or a quirk of history? Though the rationale for early combination therapy targeting normal levels of glycaemia in early diabetes is seductive, clinical trial evidence to support specific combinations and targets is essentially non-existent.

Evolving areas of current investigation will provide improvements in diabetes care and hold great hope for new treatments.

REFERENCE

Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-018-4729-5 ePub: 05 October 2018

http://diabetologia-journal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/EASD-ADA.pdf