Vulval Lichen Sclerosus: overcoming barriers to diagnosis

Amy Shirtliff BA(Hons) MSc RGN

Nurse Practitioner & Writer

VLS is a common condition but a combination of embarrassment on the part of both patients and clinicians, and lack of education, often result in lengthy delays before diagnosis and appropriate treatment

Vulval Lichen Sclerosus (VLS) is a common condition that deserves far more attention in general practice.1 It is a chronic, inflammatory skin disorder that is under-recognised and often misdiagnosed.2 It significantly affects the quality of life of many individuals, restricting their daily activities, and some women even report a loss of sense of self due to its severity.3

Estimates indicate that about 1% of women or individuals assigned female at birth (AFAB) are affected.4 VLS accounts for 25% of vulval clinic cases,1 1 in 300 dermatology referrals,2 and 1 in 70 gynaecology referrals.3 While it typically affects the vulva, 30% also affects the perineum and perianal region.2 In up to 20% of cases, it can occur in other areas of the body, such as the trunk, upper arms, buttocks and lateral thighs.5,6 It was previously thought that the vaginal canal is not affected, however rare cases in patients with prolapse suggest that vaginal involvement may be underdiagnosed.7

Although men, boys, and prepubertal girls can also be affected, this article focuses on adult women and AFAB individuals who will be seen by General Practice Nurses (GPNs). VLS predominantly occurs in those aged 45-605, typically during the peri- and post-menopausal stages.8 Drawing on recent findings from a survey published in the British Journal of General Practice (BJGP), this article explores the barriers to diagnosis and management raised, offers plenty of potential solutions, and highlights how PNs can lead improvements in care.

CAUSES, SYMPTOMS & DISEASE PROGRESSION

The cause of VLS remains unclear, although evidence suggests an autoimmune component. Autoantibodies to extracellular matrix protein 1 and concurrent autoimmune conditions, especially Hashimoto’s, have been observed, though a direct causal link hasn’t been proven.9 Autoimmune conditions and VLS may coexist without one causing the other. Familial cases are rare, with around 10% reporting an affected relative.10 VLS doesn’t compromise immunity, affect internal organs or result from infection, allergies or sexual transmission.11

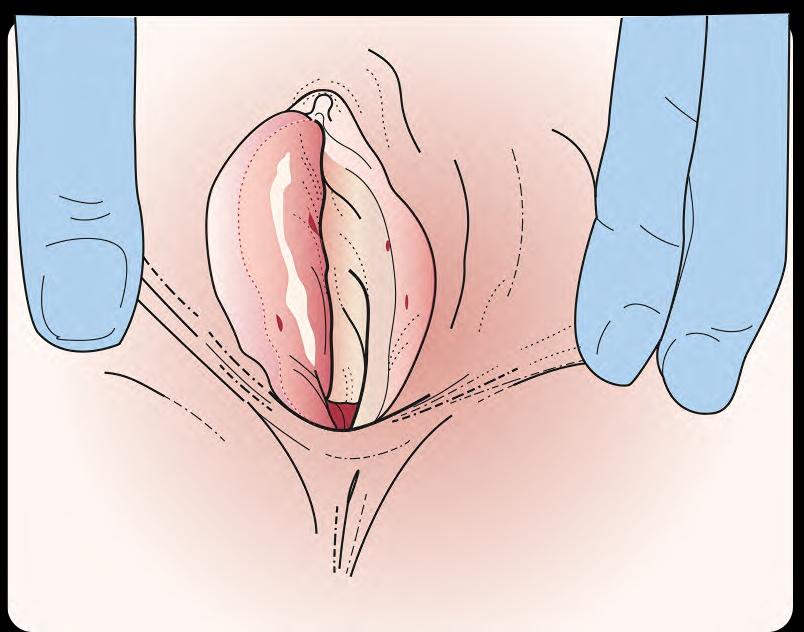

In the acute inflammatory phase, VLS initially presents as a bright red, itchy, and sore area, often worse at night.5 The sensation may also be described as burning, soreness, or dryness.4 Fragile skin may break easily from scratching, causing purpura or blood blisters. Lesions are said to resemble a ‘figure of eight’ pattern.10 Any friction or trauma (‘Koebner response’), irritation from urine leakage, or wearing incontinence pads or panty liners may exacerbate symptoms.6,10 See Box 1. For a selection of clinical images showing different presentations of VLS, visit https://dermnetnz.org/topics/vulval-lichen-sclerosus-images

BOX 1. QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER3

1. Has the woman previously presented with these symptoms?

2. Have swabs for candidiasis been negative?

3. Has the woman been prescribed or self-treated with remedies for candidiasis or Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM)?

4. Does the woman report any white patches or a change in shape of their vulval skin?

Disease progression can take months to years. Lesions develop a shiny, white or ivory appearance, becoming cracked, sore, thinning, and fragile, often resembling tissue paper.10 They may expand and merge,6 causing tightening and irreversible changes including scarring or labial fusion,12 urethral obstruction, and clitoral phimosis.2 A narrowed vaginal entrance can cause painful intercourse and skin tearing, while urethral involvement may cause dysuria and difficulty urinating.10 Peri-anal lesions can result in painful defecation, constipation issues,and occasional fissures.6,10

VLS is typically atrophic, but can appear raised, thickened, and hyperkeratotic- features associated with differentiated Vulval Epithelial Neoplasia (dVIN), a vulval cancer precursor.10,13 Cancer develops in 3-5% of VLS cases,14 representing a 20-fold increased risk.1 VLS may also reactivate latent Herpes Simplex Virus, or Human Papilloma Virus infections, particularly during active disease or with potent steroid use.13

TEACHING, TRAINING & EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

General practice clinicians manage a wide range of conditions, often with limited time and resources.15 Many receive minimal training on vulval health, leaving them underprepared to diagnose and manage conditions such as VLS. This lack of education – exacerbated by the pace of primary care –can lead to delayed or missed diagnoses and suboptimal treatment.2

The BJGP survey identified lack of knowledge as the leading barrier to diagnosing and managing VLS – 37.7% of participants had received no formal teaching or self-directed learning. Those who had training reported an average of just two hours. While clinical exposure improved confidence, 92.6% still felt further education would be beneficial. Years in practice correlated with improved confidence, highlighting the important role of experience, but formal education remains crucial.2

There is growing recognition of the need to integrate vulval health into university courses, with clinical supervision during training offering space for discussion and consolidation, especially for sensitive conditions such as VLS. For clinicians already in practice, protected time for ongoing education is vital.2 Accessible online modules and e-learning should be promoted, perhaps beyond the most commonly used platforms. (See Resources.) Additional e-learning would expand GPNs’ expertise and the knowledge gained would enhance their ability to spot conditions such as VLS.16 Training for all practice clinicians would put GPNs at the forefront due to their direct clinical exposure.17 When combined with eLearning undertaken by other healthcare professionals as well, this approach would facilitate effective knowledge sharing across the team (Box 2).16

BOX 2. MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM LEARNING

- Monthly training could feature ‘deep dive’ sessions into difficult or stigmatised conditions, helping build collective understanding.

- An anonymous reflection box could be used to suggest training topics or share experiences, while clinicians could log cases or patient feedback to inform future learning.

- Overall, a culture of openness—whether in clinical supervision, team meetings, or informal staff room chats—helps normalise learning, close knowledge gaps, and build confidence.

The study found that confidence was particularly low around initiating treatment, particularly the decision to prescribe potent topical steroids. Clinicians also reported low confidence in performing biopsies.2 Small punch biopsies are well within the scope of primary care and are recommended by several professional organisations, including the British Association of Dermatologists (BAD), the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG),and the British Association of Sexual Health & HIV (BASHH) when there is any diagnostic doubt.1,10,13 Early tissue sampling can significantly improve outcomes, and increasing training and exposure in this area could help normalise biopsy use and boost clinician confidence.1 Patient Group Directions (PGDs) for lidocaine, along with accessible biopsy training, mean that upskilling GPNs in this area is feasible and would allow them to ease some of the burden on GPs in a region of the body for which they already manage care.18

Diagnostic criteria

Clear diagnostic criteria provide a solid framework for clinicians to make accurate, timely diagnoses, helping differentiate VLS from similar conditions and streamline referrals.2,19 In conditions such as VLS, where symptoms can overlap with other disorders, standardised guidelines help distinguish between similar conditions, minimising complications and ensuring effective care. Unsurprisingly, 97.5% of BJGP study participants felt VLS diagnostic criteria would be helpful. Over half (55%) favoured an integrated diagnostic template such as Arden’s F12, while 32% would prefer a simple weblink for quick access.2

Progress is underway: The University of Nottingham’s SHELLS project has completed a consensus study and diagnostic criteria have been established. Patient collaborators are currently being recruited to guide research that is expected to conclude by 2027.20,21

In the meantime, clinicians could consider using a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) to track symptoms over time. Checklists could be incorporated into the cervical cytology template as a reminder to assess for any abnormalities during the examination. If patients are comfortable, a structured questionnaire completed during appointments would highlight symptom severity, duration, and impact – helping support more accurate diagnoses.22

Gender

Intimate examinations across gender lines can be challenging. Patients may feel exposed or anxious, especially when cultural or religious beliefs are involved. One study highlighted the difficulty male medical students had with female pelvic examinations, reporting various coping mechanisms including avoidance, overly formal behaviour, ‘getting it over with quickly’, and joking with peers afterwards.23

In the BJGP study, male clinicians reported significantly lower confidence in examining, identifying, and diagnosing vulval disease. This was closely tied to clinical exposure: female GPs reported examining vulvas weekly, while male GPs did so only two to three times a month. Many male clinicians preferred to refer these cases to female colleagues or specialists in secondary care. However, a shortage of female GPs was also seen as a barrier, given patient preference for same-gender care.2

While same-gender clinicians can offer comfort, and a sense of identification, this isn’t always possible. Practices should normalise conversations about gender in care, ensuring clear communication and informed consent to reduce patient anxiety. Informing patients in advance about appointments with clinicians of a different gender would help ease concerns. GPNs could play a key role in facilitating these discussions, supporting patients throughout the process. Additionally, practices could provide supervision and peer learning opportunities, to help male clinicians build confidence, with support from female colleagues.24

Stigma and Embarrassment

There is an inherent discomfort to intimate examinations for both the patient being examined and the clinician conducting them, particularly when rapport has yet to develop. Clinicians may fear causing embarrassment or being misperceived24. For patients, the thought of undressing and exposing intimate parts of their body can feel invasive, triggering concerns about privacy and dignity.25

In the BJGP study, patients’ reluctance to discuss vulval conditions or undergo intimate examinations was identified as a significant barrier to effective care. Many patients delayed seeking help, mistakenly believing their symptoms were a normal part of aging, which further complicated diagnosis and treatment.1 Surveys indicate that people find VLS extremely stressful to talk about, so if they do ask for help, it is because they really need it.4 This stigma surrounding vulval disease prevents open communication, making it harder for patients to articulate their concerns, especially when they are already feeling anxious.2

Clinicians should work on reducing the stigma associated with female genital conditions. The confidence to openly discuss these issues must be developed, treating them as a regular part of practice.23

BOX 3. REDUCING STIGMA

- The more confidently these topics are addressed within a healthcare setting, the more comfortable patients would feel presenting their concerns in a timely manner. Word spreads, and with widespread staff confidence, patients would be more inclined to open up.

- Staff training on intimate examinations goes beyond technical skills and needs to focus on a compassionate and empathetic approach without prejudice. Using plain language, avoiding medical jargon, and maintaining warm, reassuring body language would help normalise the conversation, making patients feel more at ease and confident discussing sensitive issues.

- To help reduce stigma, practices could introduce visible, approachable signage or a creative noticeboard in the waiting area. This could feature phrases like ‘We’ve probably seen it and much worse,’ or ‘We assess all body symptoms, wherever they occur,’ as well as references to shows like Embarrassing Bodies to remind patients that they are not alone. Such simple measures could desensitise patients to uncomfortable language and help them feel reassured that clinicians are unfazed by intimate health concerns. By subtly shifting the culture in the practice, these initiatives reinforce the message that intimate health is a priority, fostering a more open, supportive environment for patients.

- Having a trained chaperone available during intimate examinations significantly reduces patient embarrassment and provides support for clinicians. Their presence helps ensure that examinations are conducted in a respectful and professional manner. Even if a patient declines, clinicians can still request one for their own support. This practice helps foster trust, reduces anxiety, and allows patients to feel more comfortable expressing their concerns. Practice nurses can support male clinicians by acting as chaperones or mentors during sensitive exams. They are also then in a position to ease patients’ concerns.25

WORKLOAD AND HEALTHCARE STRUCTURE

The risk of diagnostic errors in general practice is high due to the large patient volumes clinicians face under time constraints. GPs must distinguish between serious conditions and non-urgent symptoms that develop slowly over time, while also adapting their approach for each individual patient. This is further complicated by systemic issues in referral procedures, which can hinder the efficiency and accuracy of diagnoses.26

The demanding workloads of GPs often result in rushed consultations, increasing the risk of missed diagnoses. Uncertainty around referral pathways also contributes to delays. Many clinicians are unsure whether vulval conditions like VLS should be managed in primary or secondary care, and telemedicine can add complexity, making timely access to specialists more difficult2 (Box 4).

BOX 4. REDUCING THE RISK OF DIAGNOSTIC ERRORS

- Perhaps the first step in avoiding diagnostic errors during a packed clinic is the conscious awareness of when those errors are more likely to occur.

- The moment a patient alludes to a vulval problem should act as a prompt for the clinician to pause, acknowledge the potential knowledge gaps in this area, and take deliberate care to assess thoroughly and sensitively.

- While it's never ideal to rush consultations, vulval symptoms particularly require additional patience – not only to ensure a correct diagnosis but to ensure patients feel heard and safe.

A focused history is crucial. Many patients have seen multiple clinicians before receiving the correct diagnosis. Asking the right questions can save months or even years of discomfort and prevent complications. Simple digital interventions could also support earlier recognition. For example, embedding prompts into clinical systems – based on features such as persistent vulval itching (particularly at night), a figure-of-eight distribution, or the presence of white, shiny plaques – could guide clinicians to consider diagnoses such as vulval lichen sclerosus and access relevant resources.3

Referral pathways may vary by region, but national guidelines confirm that primary care clinicians can diagnose VLS. When uncertain, a biopsy is recommended. If standard treatment fails or the case is complex, referral to a specialist is necessary. In some areas, specialist vulval clinics are available, while in others, dermatology or gynaecology may be more appropriate.1 NHS Advice & Guidance (A&G) services on the e-referral platform can also assist with referral decisions.27

GPNs, although not all specialists in dermatology or vulval conditions, have familiarity with vulvovaginal anatomy through everyday practice. This gives them a strong baseline for recognising when something doesn’t look right during routine procedures such as cervical cytology tests and ring pessary fittings. Early recognition of abnormalities allows them to diagnose (if able) or confidently signpost to an alternative clinician.3 Scheduling follow-up appointments themselves spares the patient the need to discuss sensitive issues in a less private area such as reception.

CONCLUSION

Overcoming the barriers to diagnosing and managing VLS in primary care is achievable through targeted strategies.2 The development of standardised diagnostic criteria is underway, which will aid clinicians in identifying VLS promptly, and more accurately.14 GPNs are instrumental in this process: their proactive involvement in patient education, routine intimate examinations, and the implementation of these criteria can significantly enhance early detection and management. By addressing knowledge gaps, reducing stigma, and streamlining referral pathways, primary care teams can ensure that patients with VLS receive timely and effective care, ultimately improving outcomes and quality of life.3

RESOURCES

- DermNet NZ. Selection of clinical images showing different presentations of VLS.

- https://dermnetnz.org/topics/vulval-lichen-sclerosus-images

- RCOG. Benign vulval conditions, https://elearning.rcog.org.uk/product?catalog=co_benignvulvalprobs

- RCGP. eLearning for GPs and primary care. Gynaecology & Breast https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/

- NHSE. eLFH hub. Lichen sclerorus – female https://portal.e-lfh.org.uk/component/details/79248

- British Society for the Study of Vulval Disease. Practitioner education and training. https://bssvd.org/practitioner-portal/educationtraining/

- British Dermatological Nursing Group. Overview of vulval conditions – on demand. https://bdng.org.uk/meetings/female-genital-dermatoses/

- Primary Care Women’s Health Society. Vulvovaginal atrophy https://www.pcwhs.co.uk/resources

Patient questionnaires

- The Vulvar Disease Quality of Life Index (VQLI) Questionnaire,28 https://bdng.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Appendix-9a.pdf (https://bdng.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Appendix-9a.pdf)

- Spectrum Dermatology of Seattle Vulvar Symptom Questionnaire,29 https://www.spectrumdermatologyseattle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Spectrum-Vulvar-Symptom-Questionnaire-7.11.22-INTERACTIVE.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOor5qEmW3Up7GkLajWz5ch41EGEFpJ15_wJhEU3rfu9aPlguz2T (https://www.spectrumdermatologyseattle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Spectrum-Vulvar-Symptom-Questionnaire-7.11.22-INTERACTIVE.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOor5qEmW3Up7GkLajWz5ch41EGEFpJ15_wJhEU3rfu9aPlguz2T)

REFERENCES

1. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. The management of vulval skin disorders: Green-top guideline No.58; 2011.https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg58/

2. Crew A, Leatherland R, Clarke L, et al. Barriers to diagnosing and treating vulval lichen sclerosus: a survey study. Br J Gen Pract 2025;75(753):250–6.

3. Rees S, Owen C, Baumhauer C, et al. Vulval lichen sclerosus in primary care: thinking beyond thrush and genitourinary symptoms of the menopause. Br J Gen Pract 2023;73(730):234-236.

4. Lichen Sclerosus Guide. Information for healthcare professionals. https://www.lichensclerosusguide.org.uk/information-for-healthcare-professionals/

5. GPnotebook. Lichen sclerosus. https://gpnotebook.com/en-GB/pages/gynaecology/lichen-sclerosus

6. Scleroderma & Raynaud’s UK. Lichen sclerosus. https://www.sruk.co.uk/conditions/lichen-sclerosus/

7. Zendell K, Edwards L. Lichen sclerosus with vaginal involvement: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. JAMA Dermatology 2013;149(10):1199–1202.

8. Macmillan Cancer Support. Vulval lichen sclerosus. https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/worried-about-cancer/pre-cancerous-and-genetic-conditions/lichen-sclerosus-vulva

9. Oyama N, Chan I, Neill SM, et al. Autoantibodies to extracellular matrix protein 1 in lichen sclerosus. The Lancet 2003;362(9378):118-123.

10. British Association of Dermatologists. Lichen Sclerosus in females. https://www.bad.org.uk/pils/lichen-sclerosus-in-females/

11. British Skin Foundation. Lichen Sclerosus (in females). https://knowyourskin.britishskinfoundation.org.uk/condition/lichen-sclerosus-in-females

12. Lichen Sclerosus Guide. Vulval Lichen Sclerosus Causes, symptoms, and signs. https://www.lichensclerosusguide.org.uk/what-is-vulval-ls/

13. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASSH). 2023 UK National Guideline on the Management of Vulval Conditions. https://www.bashh.org/userfiles/pages/files/resources/vulval_guidelines_for_consultation_2023.pdf

14. Simpson RC, Cooper SM, Kirtschig G, et al. Lichen Sclerosus Priority Setting Partnership Steering Group. Future research priorities for lichen sclerosus – results of a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. Br J Dermatol 2019;180(5):1236-1237.

15. Primary Care Workforce Commission. The future of primary care. Creating teams for tomorrow. https://napc.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Future_of_primary_care.pdf

16. Reeves S, Fletcher S, McLoughlin C, et al. Interprofessional online learning for primary healthcare: findings from a scoping review. BMJ Open 2017;(7):016872.

17. Royal College of Nursing. Genital examination in women. https://www.rcn.org.uk/-/media/royal-college-of-nursing/documents/publications/2016/march/005480.pdf

18. British Dermatological Nursing Group. Skin Biopsy Course. https://bdng.org.uk/courses/

19. Dahm MR, Cattanach W, Williams M, et al. Communication of Diagnostic Uncertainty in Primary Care and Its Impact on Patient Experience: An Integrative Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med 2023;(38):738–754.

20. SHELLS. Establishing Effective Diagnostic Criteria for Lichen Sclerosus. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/cebd/projects/vulval-and-genital-conditions/shells.aspx

21. National Institute for Health and Care Research. Addressing a neglected area of women’s health: developing diagnostic criteria for vulval lichen sclerosus. https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR301434

22. Liu J, Rothrock N, Edelen M. Selecting patient-reported outcome measures: “what” and “for whom”. Health Affairs Scholar;2024: 2(4).

23. Dabson AM, Magin PJ, Heading G, et al. Medical students’ experiences learning intimate physical examination skills: a qualitative study. BMC Medical Education 2014;(14):39.

24. Al Hejairi B, Afifi K, Rashed H, et al. Attitude and practice of family physicians towards physical examination of patients of the opposite gender in primary health care centres in the Kingdom of Bahrain: a qualitative exploratory study. BMC Primary Care 2025;(26):77.

25. General Medical Council. Intimate examinations and chaperones. https://www.gmc-uk.org/professional-standards/the-professional-standards/intimate-examinations-and-chaperones/intimate-examinations-and-chaperones

26. Cheraghi-Sohi S, Holland F, Singh H, et al. Incidence, origins and avoidable harm of missed opportunities in diagnosis: longitudinal patient record review in 21 English general practices. BMJ Quality & Safety 2021;30(12):977-985.

27. NHS England. Advice and Guidance. https://www.england.nhs.uk/elective-care/best-practice-solutions/advice-and-guidance/

28. British Dermatological Nursing Group. The Vulvar Disease Quality of Life Index (VQLI) Questionnaire. https://bdng.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Appendix-9a.pdf

29. Spectrum Dermatology of Seattle. Vulvar Symptom Questionnaire. https://www.spectrumdermatologyseattle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Spectrum-Vulvar-Symptom-Questionnaire-7.11.22-INTERACTIVE.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOor5qEmW3Up7GkLajWz5ch41EGEFpJ15_wJhEU3rfu9aPlguz2TR