Heavy menstrual bleeding

Supported by Hologic and Wearwhiteagain.co.uk

Supported by Hologic and Wearwhiteagain.co.uk

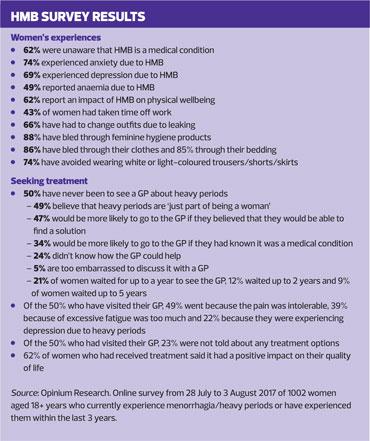

Heavy menstrual bleeding affects around 1 in 5 women, but many do not realise that this is a treatable condition, and healthcare professionals also ‘lack awareness’ of its impact on women or available treatment options. General practice nurses have a key role in starting the discussion and highlighting available treatment options.This Practice Nurse Masterclass aims to raise awareness of HMB and the latest NICE guidance. Read the article and then answer the questions at the end to assess your knowledge.

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is defined as excessive menstrual blood loss that interferes with a woman’s physical, social, emotional and/or material quality of life.1

It is one of the most common reasons for gynaecological consultations both in primary and secondary care. Approximately 1 in 20 women consult their GP each year because of heavy periods or menstrual problems, and menstrual disorders comprise 12% of all referrals to gynaecology services. HMB affects 20–30% of women of reproductive age.2

However, more than 60% of women do not realise that HMB – menorrhagia – is a medical condition,3 for which there are a number of treatment options available. And despite the relatively high consultation rates, many women do not seek advice because they feel embarrassed.4

An All Party Parliamentary Group on women’s health found a ‘chronic lack of awareness among healthcare professionals’ of two of the most common causes of HMB, fibroids and endometriosis. The APPG surveyed 2,600 women and found that more than 40% of women surveyed needed 10 or more GP appointments before being referred to a specialist, and 12% of women with fibroids took between 1 and 2 years from diagnosis to receiving treatment.5

WHAT IS NORMAL?

It can be difficult to define normal menstrual blood loss (MBL) because the duration of menstrual bleeding is so variable, although for most women menstruation lasts 3-8 days, and perception of blood loss is also both variable and subjective.6 However, adverse changes in blood chemistry – for example, in haemoglobin and ferritin levels, begin to occur when MBL exceeds 60ml.6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines menorrhagia as menstrual bleeding that lasts more than 7 days or bleeding that is very heavy, requiring a change of sanitary protection pad or tampon after less than 2 hours.7

NICE suggests that it is not clinically useful to employ the definition of HMB (60 – 80ml) used in research studies, because in practice the woman’s perception of whether her periods are having a negative impact on her physical, social and emotional experience is more useful.

You may see menstrual cycles described in shorthand, thus:

K = 7/21-35

K is the menstrual cycle, 7 is the duration of bleeding and 21-35 is the length of the cycle.8

PREVALENCE

There is huge variation in the reported prevalence of HMB or excessive menstrual bleeding. Some studies use subjective assessment, which may be influenced by cultural differences in how menstruation is perceived, while others have used more objective measures: these found that between 11% and 13.5% of women had a MBL greater than 80ml.6 However, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) estimates around 1 in 5 (20 – 30%) women of reproductive age experience HMB.

CAUSES AND RISK FACTORS

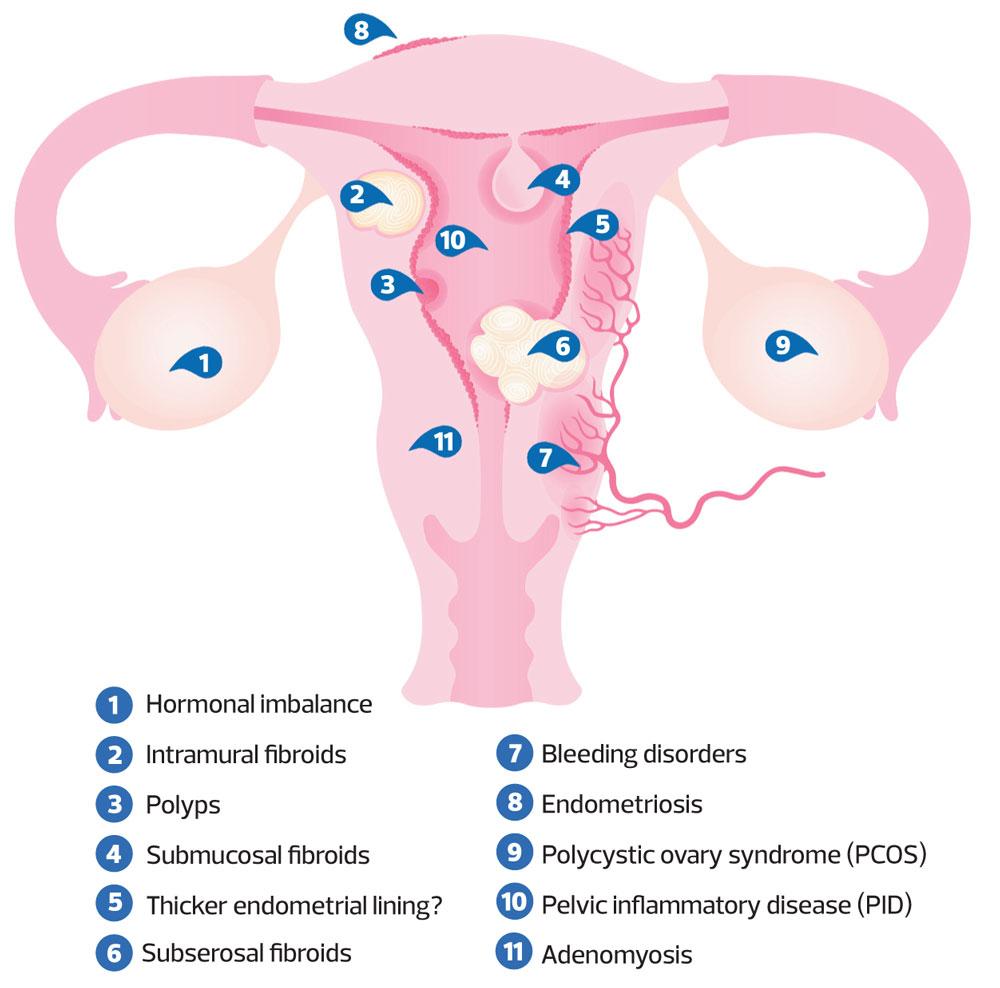

HMB is associated with a number of histological abnormalities, including:

- Uterine fibroids

– Fibroids are common, occur more frequently with increasing age, and in women of Afro-Caribbean origin than white women. The site, size and number of fibroids are linked to the level of MBL.6

- Endometriosis/adenomyosis

– The main presenting symptom of endometriosis is usually dysmenorrhoea, but HMB may be a significant secondary symptom.6

– Adenomyosis is a condition where part of the endometrium becomes embedded in the wall of the uterus, causing small pockets of bleeding within the muscle during menstrual periods, causing painful and heavy periods. It affects approximately 1 in 10 women and is most common in women aged 40-50.

- Polyps

– Uterine and endocervical polyps have been identified in women with HMB6

- Bleeding-related disorders

– von Willebrand disease and platelet function disorders are associated with HMB.2

- Non-bleeding related disorders such as liver, kidney, or thyroid disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, and cancer.2

- HMB with no obvious structural or systemic pathology is termed dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB). The diagnosis can only be made once all other causes for abnormal or heavy uterine bleeding have been ruled out.8

IMPACT OF HMB

Women are more likely to report HMB if they are experiencing psychological distress – and similarly, women who report HMB have higher rates of psychological distress than those who do not. It is not clear whether increased MBL causes mental or emotional problems, or whether mental or emotional problems increase the chances of experiencing HMB. However, there is a clear association between the woman’s perceived level of MBL and depression.6

There is no HMB-specific health-related quality of life (HRQoL) tool but one of the main reasons for consultation is the woman’s perception of the impact that HMB is having on her quality of life. The evidence suggests that HMB has a measurable effect on quality of life, particularly in respect of social interaction, and that women with HMB have higher rates of unemployment and absence from work.6 NICE states that healthcare professionals should recognise that HMB has a major impact on a woman’s quality of life and ensure that any intervention aims to improve this rather than focusing just on blood loss.1

OVERVIEW OF NICE GUIDANCE

The NICE guideline, Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management1 aims to help healthcare professionals advise women about the treatment options that are right for her, with a clear focus on the woman’s choice: it will be the woman herself who decides whether a treatment has been successful.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of HMB may be challenging, given the variability in menstrual cycles, duration of menstrual bleeding and the volume of MBL, but the process starts with taking a careful history. This should cover:

- The nature of the bleeding

- Related symptoms e.g. persistent intermenstrual bleeding, pelvic pain/pressure that might suggest uterine cavity or histological abnormality, adenomyosis or fibroids

- Impact on quality of life, including physical, social and emotional impact

- Co-morbidities or previous treatments for HMB

Period diaries may be a useful way for a woman to record menstrual loss and duration – see Resources for an example.

NICE suggests that clinicians should take account of natural variability in menstrual cycles and blood loss but if the woman feels she does not fall within normal ranges, discuss care options.1

Physical examination

If the woman has a history of HMB with other related symptoms, offer a physical examination.

Carry out a physical examination before all investigations.

Laboratory tests

Routine laboratory tests include a full blood count, and tests for coagulation disorders for women who have had HMB since their periods started or have a personal or family history suggesting a coagulation disorder.

NICE says that tests for serum ferritin, female hormone and thyroid hormone levels should not be performed routinely.1

Investigations

Before starting investigations consider starting pharmacological treatment without investigating the cause if the woman’s history and/or examination suggest a low risk of fibroids or other abnormalities. If cancer is suspected, refer following the NICE guideline on suspected cancer https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12.

The decision to offer hysteroscopy or ultrasound as first line investigation for HMB should be made according to the woman’s history and examination. NICE also recommends services are organised to enable ‘see-and-treat’ hysteroscopy in a single setting, if feasible.1 Endometrial biopsy should only be offered in the context of diagnostic hysteroctopy.1

Saline infusion sonography and MRI should not be used as first-line diagnostic tools, and dilatation and curettage (D&C) should not be used alone as a diagnostic tool for HMB.1

Appropriate investigations for adenomyosis are transvaginal ultrasound or MRI scan.1

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Provide women with information about HMB and its management, including all possible treatment options. Discussions should include:

- The benefits and risks of the options

- Suitable treatments if she is trying to conceive

- Whether she wants to retain her fertility and/or her uterus

Recommended treatments today fall into three groups: hormonal, non-hormonal or surgical.1

In women who are actively trying to conceive, non-hormonal treatments are the most appropriate option, whereas in women who want contraception, hormonal treatment can be considered. For women who no longer want to conserve their fertility, endometrial ablation, uterine arterial embolisation or myomectomy might be offered. And finally, for women who do not want to keep their uterus, a hysterectomy may be appropriate.

In practice, women with HMB may face difficulty in accessing surgery, which may only be offered after they have tried and failed various treatment strategies for a prolonged period of time.9 The evidence review on which the current NICE guideline is based states that surgical options could be considered first-line.9

NON-HORMONAL TREATMENTS

NICE recommends tranexamic acid (TXA) or NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen or mefenamic acid, for women who decline an LNG-IUS, or for whom this method is unsuitable. TXA is a plasminogen-activator inhibitor. It can reduce MBL by 50% and is most effective in menstrual loss associated with intrauterine contraception devices (IUCDs). Mefenamic acid works by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, and reduces menstrual loss by approximately 25% in 75% of women who tried it.8 The NICE guideline also recommends that women are offered TXA or NSAIDs while investigations and definitive treatment are being organised.1

The NICE evidence review points out that women with HMB caused by fibroids greater than 3cm in diameter may not respond to pharmacological treatment and may require a more invasive treatment option.9

HORMONAL TREATMENTS

The mainstay of hormonal treatments for HMB is the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), e.g. Mirena®. Other LNG-IUS are available, but neither Jaydess® nor Kyleena® is licensed for menorrhagia. Clinicians should explain to women that their bleeding pattern is likely to change, particularly in the first few cycles and possibly for more than 6 months. It is advisable to wait for at least 6 months before assessing the benefits of treatment, but many women will become amenorrheic over time.

NICE recommends LNG-IUS first line for HMB in women with:

- No identified pathology, or

- Fibroids less than 3cm in diameter which are not causing distortion of the uterine cavity, or

- Suspected or diagnosed adenomyosis

Studies show that women with HMB report more improvement in bleeding and quality of life with LNG-IUS that with other treatments available in primary care, but the rate of discontinuation is high – 34% at 2 years, and a subsequent hysterectomy rate of 42%.10

Alternatives to LNG-IUS include combined hormonal contraception or cyclical oral progestogens, which may suppress menstruation and may therefore be useful in women with HMB.

The use of ulipristal acetate (Esmya) is not currently recommended pending a European Medicines Agency (EMA) review and introduction of temporary safety measures, including not starting new courses of Esmya for uterine fibroids.1

Uterine artery embolisation

This is a procedure where an interventional radiologist uses a catheter to introduce an embolising agent into the arteries supplying the fibroid. It is less invasive than myomectomy or hysterectomy, recovery time is shorter and it may preserve fertility. However, there is a likelihood that the procedure will need to be repeated, or that surgical intervention will be needed within 2–5 years.8

SURGICAL TREATMENTS

NICE recommends only three surgical options for the treatment of HMB – second generation endometrial ablation, hysteroscopic myomectomy (for submucosal fibroids), and hysterectomy.1

ENDOMETRIAL ABLATION

This is recommended first-line if the uterus is 8

Endometrial ablation retains the uterus but fertility is not preserved. Contraception is still recommended after the procedure. Potential side effects can include vaginal discharge, and period pain, even if there is no further bleeding.

There are various types of endometrial ablation, including impedance-controlled bipolar radiofrequency ablation

(e.g. Novasure®). Microwave ablation is no longer available in the UK, and older techniques, such as free fluid thermal ablation, are not recommended.1

MYOMECTOMY

Myomectomy is the surgical removal of fibroids (uterine leiomyomas) while retaining the uterus. In contrast to hysterectomy, fertility is preserved. Typically, a laparascopic procedure is performed, unless the fibroid is very large, when open surgery may be needed. It may be possible to remove small fibroids protruding into the endometrial cavity via hysteroscopy.8

HYSTERECTOMY

In the early 1990s the most common treatment for women presenting with HMB was hysterectomy, but since then the number of hysterectomies has declined rapidly.6 Hysterectomy can be performed by a number of routes (laparascopy, laparotomy or vaginal) and may be total – the removal of the uterus and cervix, or subtotal – removal of the uterus but retention of the cervix. The ovaries should only be removed (oophorectomy) at the same time with the express wish and informed consent of the woman.1 Healthy ovaries should not be routinely removed.7

Hysterectomy is not considered first-line treatment for DUB, but may be considered if other treatments have failed, are contra-indicated or declined, if the woman wants her periods to stop (amenorrhea) and has no desire to retain her uterus and fertility. If the ovaries are also removed, the woman may experience menopausal symptoms.8

Dilatation and curettage should not be offered as a treatment option for HMB.1

HYSTEROSCOPIC MORCELLATION

This is a tissue removal procedure to remove fibroids, polyps and other intrauterine tissue. It can be performed in an outpatient setting, as the instrument is introduced into the uterus via the vagina. NICE recommends that this procedure should only be undertaken by clinicians with specific training in the technique, and should not be used if there is a possibility of malignancy.11 The Myosure® device ensures that no tissue is left in the uterus after the fibroid has been removed, to minimise risks of spreading undetected cancer cells. The rate of complications (bleeding, infection or perforation) is estimated to be <2%.

Before any surgical procedure

(i.e. hysterectomy or myomectomy), pretreatment with a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogue before should be considered if uterine fibroids are causing an enlarged or distorted uterus.

CONCLUSION

HMB is a distressing condition that can have a significant physical, psychological and social impact on affected women. HMB is a common reason for consultation in general practice, but even so, many more women fail to report it to a healthcare professional, either because they are embarrassed or are unaware that treatment is available. General practice nurses can play a key role in opening channels of communication: they have ample opportunities (during contraception and sexual health consultations, cervical screening, well woman clinics etc) to start the discussion, and if appropriate, communicate the range of treatment options available.

ASSESSMENT

Answer the questions below and then scroll down to below References to check your answers Q1. Which of the following statements best defines heavy menstrual bleeding?a. Menstrual periods lasting longer than 5 daysb. Menstrual blood loss of 60–80mlc. Menstrual blood loss sufficient to cause changes in blood chemistry,e.g. haemoglobin and ferritin levelsd. Menstrual blood loss sufficient to require a change of sanitary protection (pads or tampons) after2–4 hourse. Any menstrual blood loss perceived by the woman to be having a negative impact on her physical, social and emotional experience Q2. Which of the following conditions is NOT a recognised cause of HMB?a. Uterine fibroids (leiomyoma)b. Endometriosisc. Adenomyosisd. Hyperthyroidisme. Pelvic inflammatory disease Q3. Which laboratory tests should be carried out routinely for women presenting with HMBa. Full blood countb. Tests for coagulation disordersc. Serum ferritind. Female hormone levels (oestrogen, progesterone, FSH [follicle stimulating hormone] and LH [lutenizing hormone])e. Thyroid function tests Q4. Which treatment options can be recommended for women with HMB who wish to retain their fertilitya. Uterine arterial embolisationb. Endometrial ablationc. Non-hormonal treatments such as tranexamic acid or NSAIDsd. Myomectomye. Hormonal treatments such asLNG-IUS Q5. According to NICE, surgical treatment options for HMB can be offered first-line.True or false? Q6. Which of the following statements about endometrial ablation is false?a. Not suitable for women who want to get pregnantb. Only suitable for pre-menopausal womenc. Requires local or general anaestheticd. Cannot be reversede. Contraception no longer required

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG88. Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management, 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88/

2. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. National Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Audit. First annual report, 2011. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/research--audit/nationalhmbaudit_1stannualreport_may2011.pdf

3. Opinium Research. Online survey of 1002 women aged 18+ years who currently experience menorrhagia/heavy periods or have experienced them within the last 3 years.

4. Gupta JK, Daniels JP, Middleton LJ, et al (for the ECLIPSE Collaborative Group). Women’s experiences of medical treatments for heavy menstrual bleeding: a longitudinal qualitative study. Health Technology Assessment, No. 19.88. NIHR Journals Library. 2015 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321928/

5. All-Party Parliamentary Group On Women’s Health. Informed Choice? Giving women control of their healthcare, March 2017 http://www.appgwomenshealth.org/news/2017/3/27/the-all-party-parliamentary-group-on-womens-health-report-launched

6. NICE/National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Heavy menstrual bleeding. Full guideline, 2007. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-4782291810

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bleeding disorders in women: heavy menstrual bleeding, 2015 (Last reviewed, December 2017). https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/blooddisorders/

women/menorrhagia.html

8. Harding M. Menorrhagia (for medical professionals). https://patient.info/doctor/menorrhagia

9. NICE NG88. Evidence reviews for management of heavy menstrual bleeding, 2018 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88/evidence/evidence-review-b-management-of-heavy-menstrual-bleeding-pdf-4782293102

10. Hurskainen R, Teperi J, Rissanen P, et al. Clinical outcomes and costs with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or hysterectomy for treatment of menorrhagia. JAMA 2004;291:1456-1463

11. NICE IPG522. Hysteroscopic morcellation of uterine fibroids, 2015 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg522/chapter/1-Recommendations

ASSESSMENT ANSWERS

ANSWER 1It can be difficult to define normal menstrual blood loss (MBL) because the duration of menstrual bleeding is variable, (3-8 days), and perception of blood loss is also both variable and subjective. Changes in blood chemistry, e.g. haemoglobin and ferritin levels, begin to occur when MBL exceeds 60ml. The definition of HMB used in research studies is 60 – 80ml, and the CDC defines HMB as bleeding that lasts more than 7 days or that requires a change of sanitary protection pad or tampon after less than 2 hours. However, in practice the woman’s perception of whether her periods are having a negative impact on her physical, social and emotional experience is a more useful definition. ANSWER 2Hypothyroidsim, not hyperthyroidism, is a recognised cause of heavy menstrual bleeding. Other possible causes of HMB include polycystic ovary syndrome, blood clotting disorders, cancer and some medical treatments such as the intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) as distinct from the LNG-IUS, anticoagulants, and chemotherapy. ANSWER 3The only laboratory test that should be performed routinely in all women presenting with HMB is the full blood count. Tests for coagulation disorders should be performed in women who have had HMB since their periods started, or who have a personal or family history suggesting a coagulation disorder. NICE states tests for serum ferritin, female hormone and thyroid hormone levels should not be performed routinely. ANSWER 4In women who are actively trying to conceive, non-hormonal treatments are the most appropriate option, whereas in women who want contraception, hormonal treatment can be considered. First-line hormonal treatment is the LNG-IUS but note that not all products have a license for this indication. Uterine arterial embolisation or endometrial ablation should only be considered for women who no longer want to conserve their fertility, as fertility cannot be guaranteed after the procedure. ANSWER 5True. Hysterectomy is not considered a first-line treatment for HMB where there is no obvious structural or systemic pathology (dysfunctional uterine bleeding) but other surgical options can be considered, such as endometrial ablation, taking into account the benefits and risks of the options, and whether or not the woman may want to conceive in future. ANSWER 6The false statement is ‘Contraception no longer required’. Endometrial ablation is not suitable for women who want to get pregnant, as fertility is unlikely to be preserved. However, while pregnancy after ablation is not likely, it is possible. The woman should be advised to continue to use contraception until after the menopause as pregnancy after ablation carries a high risk of complications, including miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, and caesarean delivery.Kohn JR et al. Pregnancy after endometrial ablation: a systematic review. BJOG 2018;125(1):43-52