Providing a travel health service in primary care

JANE CHIODINI, MBE

JANE CHIODINI, MBE

MSc(TravelMed), RGN, RM, FFTM, RCPS (Glasg), QN

Past Dean, Faculty of Travel Medicine

Practice Nurse 2022;52(7):17-21

Those with limited knowledge on the subject of travel medicine tend to consider it as no more than ‘travel vaccs’. But travel medicine is complex and has far wider ranging considerations than just vaccine preventable illnesses

The travel industry has been severely affected in recent years with the impact of COVID-19, which highlighted the ability for disease to spread rapidly as a result of modern transportation. However, infectious and non-infectious risks have always been a threat with international travel.

At the time of writing, the World Health Organization has declared outbreaks of monkeypox in 75 countries as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).1 It is hoped that these types of declarations result in the world taking greater notice of the potential threat and introduce more stringent measures to tackle such events, including work on preventive strategies, for example vaccine development. Regular meetings are held to discuss and measure progress of any particular PHEIC event and they are usually not long in place, although the risk of polio has been a PHEIC since 2014.2

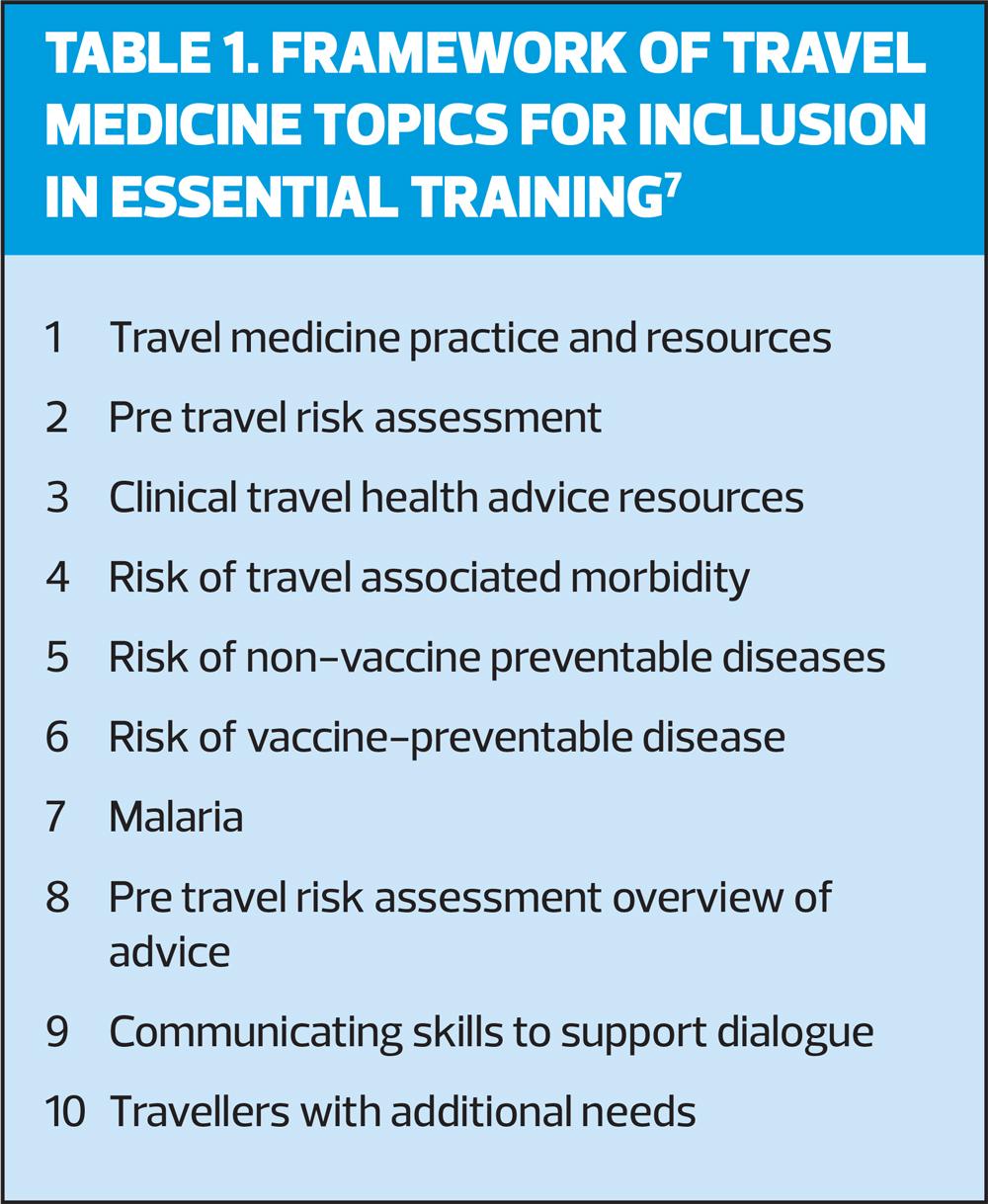

Those with limited knowledge on the subject of travel medicine tend to consider the topic only with reference to ‘travel vaccs’. Undoubtedly, the availability of such immunisations is important when there is a vaccine preventable consideration, but this represents an exceedingly small risk in comparison to events such as road traffic injuries and non-vaccine preventable illnesses, for example travellers’ diarrhoea.3 Travel medicine is complex (see Table 1) and has far wider ranging considerations than just the vaccine preventable illnesses, which must be determined within a careful pre-travel risk assessment. Following this process, decisions can then be made on the individual risk and management advice, which then need to be discussed with the traveller.4

GOVERNANCE OF A SAFE PRE-TRAVEL HEALTH SERVICE

In the UK, there is no regulation for pre-travel health practice apart from the structure of governance for the administration of yellow fever vaccine. Due to International Health Regulations (IHR) there is stipulation that vaccine can only be administered at centres designated by the health administration for the territory in which they are situated.5,6 However, all healthcare professionals must abide by their professional code of conduct. Added to this, there are three recent publications,4,7,8 which add weight to the argument that irrespective of which professional group is delivering care, each person doing so must exceed the minimum standard of practice and meet the health needs of the individual traveller.5

Registered doctors, nurses and pharmacists all deliver travel health care, but it is feasible for other registered healthcare professionals to do so as well, as long as they have adequate training. This would include the newer registered profession of Nursing Associates, although at the current time they are excluded by legislation from administering vaccines under a Patient Group Direction (PGD).9

RCN Competencies

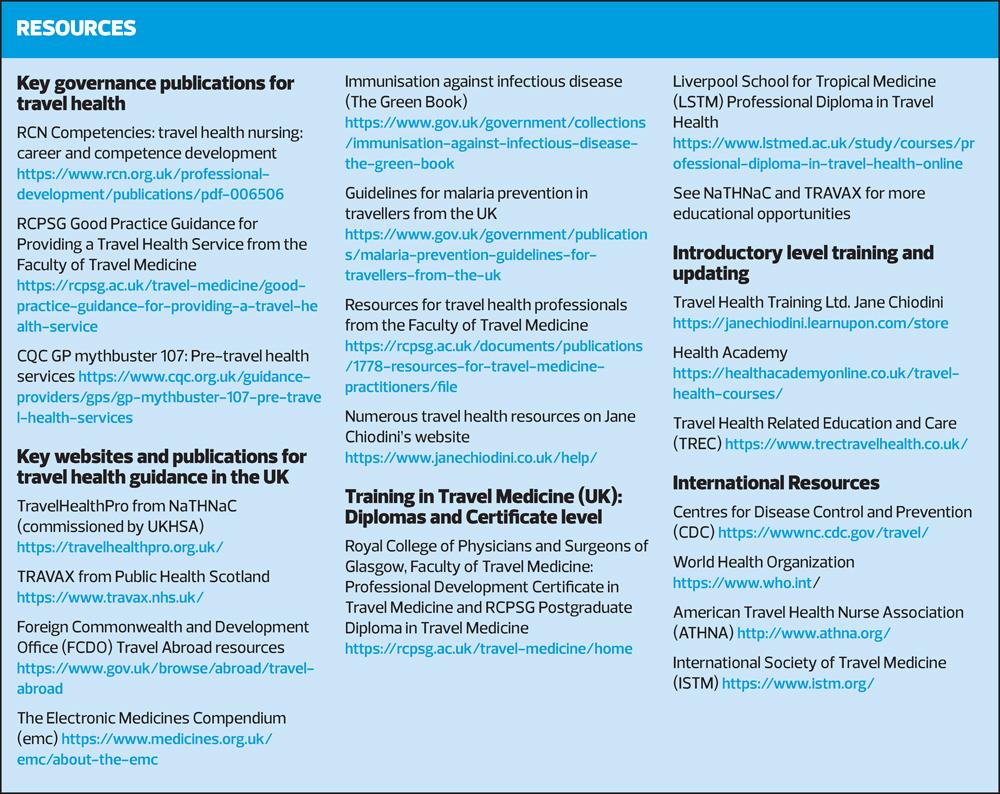

The RCN’s Travel health nursing: career and competence development4 was first published in 2007, updated in 2012 and 2018 and is currently going through a further review, expected to be republished later in 2022. This RCN publication was the first of its kind to outline travel health nursing to aid career and competence development and formed the initial catalyst for guidance to be developed in many other countries around the world. It includes a description of the pre-travel risk assessment and management and describes competencies at three levels, to help the nurse progress in their expertise in this field of practice. It forms a very practical guide, particularly for the practitioner newer to travel medicine and if a novice to this area, is essential reading.

Good Practice Guidance (GPG) for Providing a Travel Health Service

This publication from the Faculty of Travel Medicine,7 was published in October 2020 by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (RCPSG), and considers four sections:

1. Service delivery

2. Operational/Facility Requirements for a Travel Service

3. Assurance and Governance of Travel Health Services

4. Recommendations for the Practice of Travel Medicine

It sets out the key aspects of a travel health service including:

- The standard of care all travellers should expect to receive

- The fact that care should be delivered to the same standard, no matter what the background of the person delivering that care

- The minimum acceptable setting and equipment required in which to perform the travel consultation

- The requirement for training in travel medicine, an outline of a curriculum for an introductory course, and a description of the minimum requirement of the trainer

- Further training and ongoing CPD for those practising in travel medicine

- A competency assessment tool for all practitioners to use at any level of expertise, ensuring standards of care are maintained from starter level to those more experienced

All those involved or interested in becoming involved in travel medicine, including setting up a service should study this publication and its accompanying appendices.

Care Quality Commission GP mythbuster 107: Pre-travel health services

The CQC has also published advice that is applicable for those providing a travel health service in England, both in the NHS and independent sectors.8

It describes the importance of governance including acceptance that in general practice, the duty of care for travel health is often delegated to the general practice nurse (GPN), but that under the General Medical Council’s Good Medical Practice, the GP delegating must be satisfied that the person nurse providing care has the appropriate qualifications, skills and experience to provide safe care for the patient. It continues to state that all staff they manage must have access to appropriate training and supervision. It outlines that training is required, in line with the RCN competency and GPG frameworks, but there should also be evidence of formal immunisation training, and ongoing evidence of competence plus safeguarding competence at the appropriate level. Practitioners administering yellow fever vaccines must also meet the standards required under the administration of the National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC). The mythbuster continues to outline evidence that may be requested upon their inspections including:

- Using a recognised online tool to identify country-specific risks to help make recommendations. Country-specific risks include vaccine-preventable and mosquito-borne diseases.

- A comprehensive travel health risk assessment completed for each person using the service

- Clear documentation of the risk assessment for all vaccines given, medicine prescribed, or advised, and vaccines declined

- Safe recruitment and induction

- Reviewing pre-travel consultations until the practitioner has reached the minimum standard of proficiency

Again, all those working in this field of practice should study this CQC mythbuster and it also makes a useful reference point for anyone not practising in England or governed by the CQC, for good standards of care and best practice.

PRIMARY CARE PROVISION OF PRE-TRAVEL ADVICE

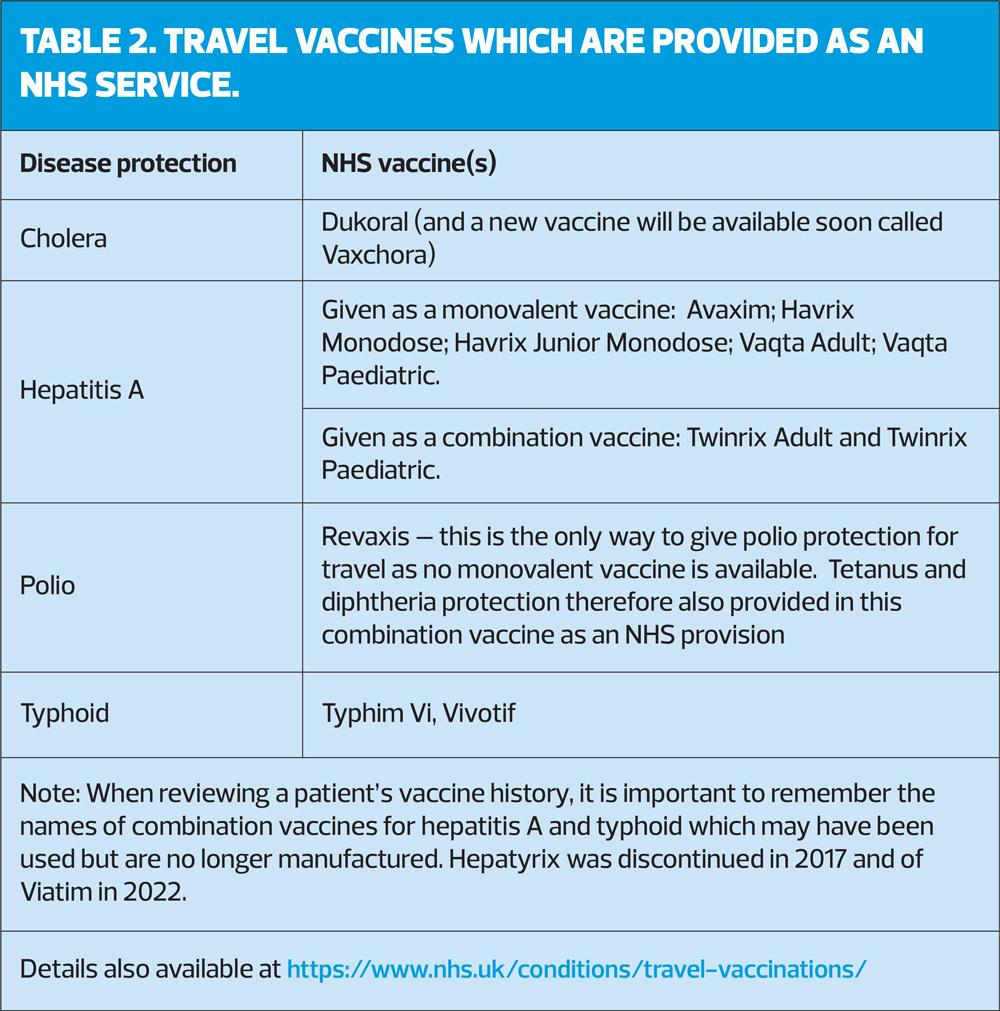

Travel health has been provided in primary care since the 1966 GP contract. Such care was deemed of public health importance for diseases such as polio, cholera, hepatitis A and typhoid as these faecal-oral infections are easily spread in a local population. So it was decided to administer immunisations to protect against such diseases in relation to travel abroad as an NHS funded provision as described in Table 2. In more recent times, travel was part of additional immunisation services and a GP surgery was allowed to opt out if they officially declared it, then an alternative provider would be identified. However, since 2020, travel health has been part of the ‘core’ GP contract and so currently, it must be provided in general practice.10 There has been much discussion about this with many surgeries deciding they will still not provide a service. However, the CQC mythbuster states this is a requirement and identified the scope of this care as follows:

- Pre-travel risk assessments

- Travel health advice including malaria prevention

- Advising which vaccines are available on the NHS

- Directing travellers to another provider for advice on non-NHS vaccines, as necessary.

In Scotland the NHS vaccines are still provided, but as part of the new GMS contract in 2018 it was decided to deliver vaccinations services in a different way and this included travel health services. A Vaccine Transformation Programme was developed and – although delayed by COVID-19 – it came into force in April 2022. Each Health Board in Scotland is responsibility for the delivery of travel health services that have largely been removed from primary care. The models vary by region, supported by the fitfortravel website which includies a landing page to signpost individuals to Travel Health Services in their local areas.11 Implementation is still in the early stages, but essentially while travel health care continues to be delivered, in the main it is no longer provided by GPNs.

THE TRAVEL CONSULTATION IN THE POST-COVID ERA

Perhaps a benefit of the pandemic was the speed with which practitioners became more familiar with different technologies and care delivery systems. Although a face to face consultation is still beneficial, it is also possible to conduct a pre travel risk assessment online in a video call, where sharing of the computer screen could also lend itself as an excellent way of educating the traveller and encouraging them to take more responsibility for reading about the risks of their trip. They could then be advised to attend the surgery for the vaccine administration, which allows time in advance for a prescription or patient specific direction to be signed, for example. No matter which method is used, adequate time is still required. The minimum time possible for an uncomplicated travel risk assessment should be 20 minutes, but more complex cases and/or those requiring malaria prevention advice will require longer than this, a minimum of 30 minutes. Similarly, administration of yellow fever vaccine is very complex with many checks required prior to administration, so this aspect alone can take a 30-minute appointment.

GUIDANCE FOR THOSE NEW TO TRAVEL HEALTH

If you are new to travel health, it is very important that you undertake an introductory course in the subject. There are a number of courses available delivered as in-person, online or e-learning formats. There are advantages and disadvantages to each method, very much dependent on the type of learner the student is. Therefore, it is important to look around before committing to training, looking at who the trainer is, their qualifications and experience, if the course content follows the aforementioned GPG document,7 and availability of the training.

Any such course can enlighten the student regarding the complexity of travel health, aid awareness of the resources to use for support and help. However, no ‘classroom-based’ learning can make the student competent. That comes with time, practice and experience. Mentorship has an important place to play in this aspect and is considered essential once the academic training has been completed. The GPG provides a competency assessment tool, which should be used to validate this stage of learning, both within the guidance document itself, but also as a downloadable editable Word file which can be used as a ‘living document’ for ongoing experience in the subject. By completing this, one can also then identify gaps of knowledge for further training as part of one’s continuing professional development (CPD).

The GPG states it is the responsibility of each workplace/organisation to ensure that practitioners new to travel medicine practice have access to supervised practice. Such a person needs to have good up to date knowledge of travel medicine with evidence of clinical practice in this field. It is also stated that it would not be good practice for a new practitioner to undertake a pre-travel consultation without completing appropriate workplace learning and competency sign off.7 Full details of the process and use of the competency assessment tool can be found within the guidance. Such evidence of competence is now routine for many other areas of care, for example, following a two day immunisation training course, prior to managing the child immunisation appointment,12 and this standard of care became normal practice prior to the COVID-19 immunisations programme.13 Indeed, national PGDs stipulate training is required prior to their use.15 In addition, the immunisation guidance adds that if giving travel vaccines, then additional travel health training is required, a generic immunisation course alone would not be sufficient.16 These requirements are also supported by the CQC.8

Travel health practice is disliked by some GPNs yet really enjoyed by considerable numbers of others. No two travellers will be the same, and even if they have chronic medical conditions they are usually ‘excited’ by their planned travel abroad. Consultations can be very rewarding and refreshing for the practitioner, a break in the routine of many GPN tasks. Therefore, good knowledge and understanding gained by thorough foundation training can help gain confidence when working in this field.

GUIDANCE FOR THOSE MORE EXPERIENCED IN TRAVEL HEALTH

Travel is normally a fast moving field of practice. This hasn’t been the case during the recent pandemic, leaving many practitioners feeling quite out of touch with practice and therefore apprehensive. The RCN states an annual update is preferred,4 but it is also acknowledged that GPNs have many areas of practice in which they need to ensure they are up to date. However, if practising, it would be necessary to have regular training and feel confident one is up to date.

Although bespoke training would be optimal, there are other ways of ensuring the latest changes and news are followed. These could include signing up to the news updates sent out regularly from NaTHNaC and TRAVAX (subscription currently required if working in England, Wales and Northern Ireland). Experts can also be followed on social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter. There are frequent questions posted on GPN Facebook forums which raise awareness of common queries, but if you follow and/or contribute to these, then great care must be taken to evidence responses. In general, specific clinical enquiries would be ill advised and could be in breach of the NMC Code.17 For those who truly enjoy travel medicine, further training would always be recommended to extend experience and knowledge. Courses are available at Certificate and postgraduate Diploma level. There are also international groups that offer education and support, along with large conferences as well. (See Resources)

WHAT IF YOU WANT TO SET UP A TRAVEL SERVICE?

There are many aspects to consider when setting up a service, too many to include in this article. Setting up a bespoke service means confirming that a provider has a specific expertise, so comprehensive training, and preferably a qualification, is desirable. Studying the three guidance documents described in the governance section is important. Further considerations for setting up a service will include the following topics, to be addressed in a future article:

- Training

- Regulatory bodies

- Market considerations and financial implications

- Premises, equipment, and vaccine storage

- Emergencies

- Procedures and protocols

- Operational considerations

- Consumables, vaccines and drugs

- Staff training and investment costs

- Traveller products, literature and resources.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General's statement at the press conference following IHR Emergency Committee regarding the multi-country outbreak of monkeypox; 23 July 2022 https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-the-press-conference-following-IHR-emergency-committee-regarding-the-multi--country-outbreak-of-monkeypox--23-july-2022

2. World Health Organization. Poliovirus IHR Emergency Committee; 2022 https://www.who.int/groups/poliovirus-ihr-emergency-committee

3. Steffen R. (2018) Travel vaccine preventable diseases—updated logarithmic scale with monthly incidence rates vaccine preventable. J Travel Med 2018; 25(1), Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/tay046

4. Royal College of Nursing. Competencies: travel health nursing: career and competence development; 2018 https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pdf-006506

5. National Travel Health Network and Centre. Becoming a Yellow Fever Vaccination Centre (YFVC) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (EWNI). https://www.nathnacyfzone.org.uk/become-a-yfvc

6. Public Health Scotland (2021) Designation of Yellow Fever Vaccination Centres Information Pack; 2021 https://publichealthscotland.scot/publications/designation-of-yellow-fever-vaccination-centres-information-pack/designation-of-yellow-fever-vaccination-centres-information-pack/

7. Chiodini JH, Taylor F, Geary K, et al. Good Practice Guidance for Providing a Travel Health Service; 2020. Faculty of Travel Medicine of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. https://rcpsg.ac.uk/travel-medicine/good-practice-guidance-for-providing-a-travel-health-service

8. Care Quality Commission. GP mythbuster 107: Pre-travel health services; 2022 https://www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-providers/gps/gp-mythbuster-107-pre-travel-health-services

9. Royal College of Nursing. Medicines Management: an overview for nursing; 2020 https://www.rcn.org.uk/clinical-topics/medicines-management/patient-specific-directions-and-patient-group-directions

10. BMA Update to the GP contract agreement 2020/21 – 2023/24 https://www.bma.org.uk/media/2024/gp-contract-agreement-feb-2020.pdf

11. The Scottish Government. Vaccination Transformation Programme – Travel Health Services; 2022 https://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/cmo/CMO(2022)13.pdf

12. Royal College of Nursing. Immunisation Knowledge and Skills Competence Assessment Tool; 2022. https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/immunisation-knowledge-and-skills-competence-assessment-tool-uk-pub-010-074

13. UKHSA. COVID-19: vaccinator competency assessment tool; 2021 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-vaccinator-competency-assessment-tool

14. UKHSA. Immunisation training standards for healthcare practitioners; 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-minimum-standards-and-core-curriculum-for-immunisation-training-for-registered-healthcare-practitioners

15. UKHSA. Immunisation patient group direction (PGD) templates; 2022 https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-patient-group-direction-pgd

16. UKHSA. Immunisation training standards for healthcare practitioners; 2018 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-minimum-standards-and-core-curriculum-for-immunisation-training-for-registered-healthcare-practitioners

17. Nursing & Midwifery Council. Social media guidance; 2022 https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/guidance/social-media-guidance/