Vaping, smoking and quitting: a new dilemma

Mandy Galloway

Mandy Galloway

Editor, Practice Nurse

A spate of cases of vaping-related lung disease – including some fatalities – have prompted fresh concerns about the safety of e-cigarettes, but PHE still says they are less dangerous than smoking. So can we still recommend vaping to people who want to quit?

There has been a big increase in the number of people in the United States with a severe lung condition apparently related to vaping. US public health officials are currently investigating more than 800 cases of vaping-induced lung injury.1

The majority of cases (67%) have occurred in people, aged 18 to 34, and at the time of writing, there have been 12 deaths in the US, and one reported in Canada.1 There has also been a recent report in the national press that the death of a man in the UK, in 2010, has now been attributed to lipoid pneumonia caused by vaping.

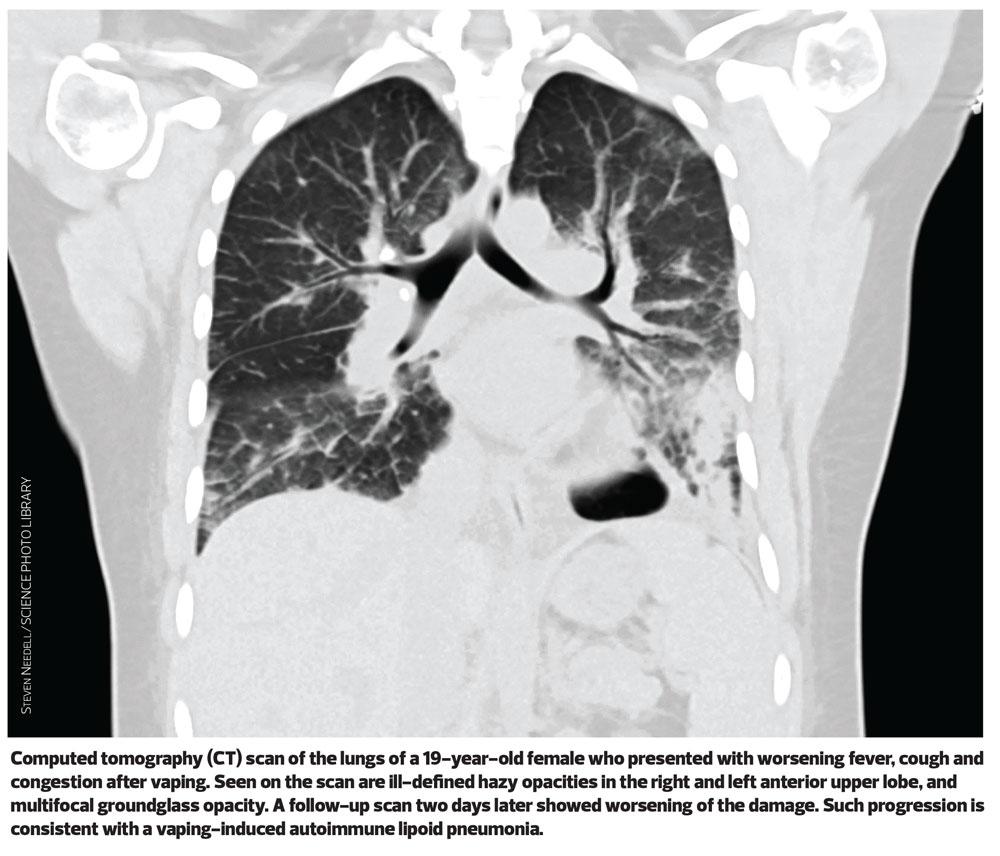

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says that in most cases, patients reported a gradual onset of symptoms including breathlessness, breathing difficulties and chest pain.1 Patients have been found to have abnormalities on chest imaging, including lipoid pneumonia – an inflammatory response to the presence of lipids in the alveoli typically caused by aspiration of oil-based products.2

So far the specific chemical or chemicals causing the lung injuries remain unknown, but 77% of those affected admitted using e-cigarettes containing tretrahydocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive chemical in cannabis. However, some 16% of patients with the ‘mystery lung disease’, claim they used products containing only nicotine.1

The CDC has advised people to ‘consider refraining’ from e-cigarette use until more is known – but not to return to smoking tobacco.

Public Health England tweeted ‘our advice on e-cigarettes remains unchanged – vaping isn’t completely risk free but is far less harmful than smoking tobacco. There is no situation where it would be better for your health to continue smoking rather than switching completely to vaping.’3

‘What little we know of recent reports from the US is that the devices used appear to be linked to “home brews” of illicit drugs and not legitimate vaping products,’ says Martin Dockrell, head of tobacco control at Public Health England, stated last month (September 2019). ‘So far there is no evidence of an outbreak of the vaping-related illness that occurred in the US in the UK or other European countries.’

The EU’s Tobacco Products Directive restricts not only the labelling, packaging and advertising of e-cigarettes but also restricts liquids used in vaping devices to a nicotine strength of no more than 20mg/ml – but in the US, some products contain 59 mg/ml, making them far more potent. One example, the ‘5%’ nicotine Juulpod contains the amount of nicotine found in two packs of cigarettes.

PHE tweeted: ‘All UK e-cigarette products are tightly regulated for quality and safety by the MHRA. It is important to use UK-regulated e-liquids and never risk vaping home-made or illicit e-liquids or adding substances, any of which could be harmful.’3

Some experts have criticised PHE’s stance, saying it overlooks a case reported in the BMJ by respiratory physicians at Birmingham Heartlands Hospital of a young woman exhibiting exactly the same symptoms and a similar history of vaping to the cases emerging in the US.4

Last year, PHE published an evidence review that found that vaping poses only ‘a small fraction of the risks of smoking – at least 95% less harmful.’5

VAPING MYTHS

PHE has also issued myth-busting advice, covering commonly held concerns:6

Myth: ‘e-cigarettes might cause “popcorn lung”.’

Some flavourings used in e-liquids to provide a buttery flavour contain the chemical diacetyl, which at very high levels of exposure has been associated with the serious lung disease bronchiolitis obliterans, initially observed among workers in a popcorn factory.6

However, diacetyl is banned as an ingredient from e-cigarettes and e-liquids in the UK. It had been detected in some e-liquid flavourings in the past, but at levels hundreds of times lower than in cigarette smoke. Even at these levels, smoking is not a major risk factor for this rare disease.6

The UK has some of the strictest regulations for e-cigarettes in the world. Under the Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016, e-cigarette products are subject to minimum standards of quality and safety, as well as packaging and labelling requirements to provide consumers with the information they need to make informed choices.

All products must be notified by manufacturers to the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), with detailed information including the listing of all ingredients.

Myth: ‘e-cigarettes contain nicotine, and nicotine causes cancer’

Four out of 10 smokers and ex-smokers wrongly think nicotine causes most of the tobacco smoking-related cancer, when evidence shows nicotine actually carries minimal risk of harm to health. Although nicotine is the reason people become addicted to smoking, it is the thousands of other chemicals contained in cigarette smoke that causes almost all of the harm.6

e-cigarette vapour does not contain tar or carbon monoxide, two of the most harmful elements in tobacco smoke. It does contain some chemicals also found in tobacco smoke, but at much lower levels.

PHE’s 2018 evidence review found that to date, there have been no identified health risks of passive vaping to the health of bystanders.5

Myth: ‘e-cigarettes are a route into smoking among young people’

UK surveys show that young people are experimenting with e-cigarettes, but regular use is rare and confined almost entirely to those who already smoke.7

There is also no evidence to support the assertion that vaping is ‘normalising smoking’. In the years when adult and youth vaping in the UK were increasing, the numbers of young people believing that it was ‘not OK’ to smoke was accelerating. Smoking rates among young people in the UK continue to decline.6

Myth: Vaping doesn’t help smokers quit

A major UK clinical trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) and involving nearly 900 participants, found that in UK Stop Smoking Services, a standard e-cigarette was twice as effective at helping smokers to quit compared with the quitters’ choice of combination nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). The 1-year abstinence rate was 18.0% in the e-cigarette group, as compared with 9.9% in the NRT group. Both groups were provided with behavioural support and those in the e-cigarette group had significantly faster reductions in cough and phlegm.8

STOPTOBER IS BACK

Although tobacco-smoking rates are falling at their fastest rate in over a decade, with around 200 fewer smokers every hour,9,10 millions of people in the UK still smoke and the annual national campaign to help encourage smokers to make a quit attempt – Stoptober – launched on 1 October.

Yvonne Doyle, Director for Health Protection and Medical Director at PHE, said: ‘It’s really encouraging to see these early signs of such a fast drop in smokers but we’ve still got a way to go to achieve our ambition of a smoke-free society. That’s why Stoptober is back and we are encouraging all smokers to take part.

‘Giving up smoking is the best thing a smoker can do for their health and it can also help save money – in just 28 days smokers will start to notice so many benefits.’

Stoptober has supported over 1.9 million people on their quit journey to date – if a smoker can remain smokefree for 28 days, they are five times more likely to quit for good.10

PHE states: ‘Anyone who has struggled to quit should try switching to an e-cigarette and get professional help. The greatest quit success rate is among those who combine using an e-cigarette with support from a local stop smoking service.’5

Given the evidence coming out of the US, is it still a good idea to recommend

e-cigarettes as an aid to smoking cessation?

It is estimated that approximately 2.9 million adults in the UK currently use

e-cigarettes, and of these, 1.5 million have stopped smoking completely.11

But according to a recent US review,11 there is limited evidence to support ‘the claim that e-cigarettes assist chronic smokers in quitting combustible cigarettes… several randomised and observational studies have been conducted to address this issue; however, no clear consensus has emerged.

‘It seems likely that the availability of e-cigarettes is leading to net increases in the numbers of both nicotine-dependent users and combustible cigarette smokers.’12

While the NEJM study found that e-cigarette users were twice as likely as NRT-users to be abstinent at 1 year,6 critics point out that 80% of e-cigarette users are likely to still be vaping after a year – whereas only 9% of NRT users were still using nicotine.12

Currently, e-cigarettes cannot be provided on an NHS prescription – even though the NHS and PHE recommend them as an aid to smoking cessation. Even Stop Smoking services can’t prescribe e-cigarettes as none are available as a licensed medicinal product, but tobacco addiction experts say that an effective e-cigarette available on prescription would be ‘welcome... it’s important to ensure that smokers who want to switch to vaping have a wide choice of e-cigarettes available to them and ways of easily accessing them.’

However, in the light of the alarming reports of vaping-related lung disease, it is not beyond the realms of possibility that healthcare professionals may start to see e-cigarette users who want help to quit vaping.

There are currently no protocols to inform practice in this context, but a case report from 2016 illustrates how NRT might be useful.12 It tells the story of a young man who, having used e-cigarettes to stop smoking, found he was unable to stop vaping. He was enrolled into a stop smoking programme, and was initially prescribed an NRT patch plus lozenges, together with strategies for behavioural change. At first he had little success, but after switching to lozenges alone (in the flavour of his preferred vaping product) he quit e-cigarettes completely within 12 weeks, and gave up NRT after a further 6 months.13

The case report raised interesting questions for the prescriber, including the challenge of estimating an appropriate dose of NRT to recommend. This is usually calculated based on the number of cigarettes smoked – but as we have seen, the amount of nicotine in an e-cigarette can vary considerably, and patients’ reports of nicotine consumption may therefore be inaccurate. The advice from this study is to monitor and quantify, as best possible, NRT and continuing e-cigarette use to refine treatment recommendations.13

THE BOTTOM LINE

- e-cigarettes may not be as ‘safe’ as previously thought but both the type of products available and patterns of use in the US are very different from those available in the UK.

- Vaping is still likely to be far less harmful than smoking conventional cigarettes and the use of e-cigarettes can be recommended as a way of giving up smoking – but may not help to overcome nicotine addiction.

- It is important that people who choose to use e-cigarettes purchase legitimate products – UK-regulated e-liquids – and do not risk vaping home-made or illicit e-liquids or adding substances to them, any of which may increase the risk of harm.

- Finally, for people who want advice on how to stop vaping, the same approach as used in conventional smoking cessation may be successful, but it may take trial and error to establish the most effective product or combination, and an appropriate dose.

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarettes use or vaping. 27 September 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/

tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

2. Henry TS, Kanne JP, Kligerman SJ. Imaging of vaping-associated lung disease. N Engl J Med 2019, ePub 6 September 2019. DOI:10.1056/NEJMc1911995

3. Public Health England (PHE). Twitter, 12 September 2019 https://twitter.com/PHE_uk/status/1172165913539469319

4. Viswam D, Trotter S, Burge PS, et al. Respiratory failure caused by lipoid pneumonia from vaping e-cigarettes. BMJ Case Reports 2018;2018:bcr-2018-224350

5. PHE. e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products: evidence review 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/e-cigarettes-and-heated-tobacco-products-evidence-review

6. PHE. Clearing up some myths around e-cigarettes, February 2018. https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2018/02/20/clearing-up-some-myths-around-e-cigarettes/

7. Hajek P, Phillips-Walker A, Przulj, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine replacement therapy. N Engl J Med 2019;380:629-637

8. Bauld L, Mackintosh Am, Eastwood B, et al. Young people’s use of e-cigarettes across the United Kingdom: Findings from five surveys 2015-2017. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14(9). doi:10.3390/ijerph14090973

9. University College London (UCL). Smoking Toolit Study. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/health-psychology/research/Smoking_Toolkit_Study

10. PHE. Fastest drop in smoking rates in over a decade as Stoptober launches. Press release, 19 September 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/fastest-drop-in-smoking-rates-in-over-a-decade-as-stoptober-launches

11. NHS Smokefree. e-cigarettes. https://www.nhs.uk/smokefree/help-and-advice/e-cigarettes

12. Bhatnagar A, Payne TJ, Robertson RM. Is there a role for electronic cigarettes in tobacco cessation. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8(12):e012742

13. Silver B, Ripley-Moffitt C, Greyber J, et al. Successful use of nicotine replacement therapy to quit e-cigaretttes: lack of treatment protocol highlights need for guidelines. Clin Case Rep 2016;4(4):409-411

Related articles

View all Articles