Inhaler devices, technique and errors: an overview

PRACTICE NURSE

PRACTICE NURSE

Staff writers

This promotional supplement has been initiated, funded and reviewed by Napp Pharmaceuticals Limited. A link to prescribing information can be found at the end of this article

Medication delivered by an inhaler is the most common treatment for virtually all respiratory diseases, and the choice of devices and treatment options is vast. Yet poor inhaler technique is commonplace and is linked to poor outcomes

Poor inhaler technique is a frequent finding when patients with respiratory disease are accurately assessed by an appropriately trained healthcare professional. Common errors are well described in relevant literature,1-3 and a set of national standards, published by the UK Inhaler Group, aims to support healthcare professionals to identify and address these errors in their patient population.4 More recently, a guide to selecting the most appropriate inhaler for each individual patient has been produced by experts in the field.5 Recent research has identified firm links between incorrect inhaler use and poor health related outcomes.6

BACKGROUND

Poor asthma control is common and is associated with increased risk of exacerbations and reduced lung function.7,8

In the largest study of its kind, the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey of patients with asthma found that only 20% had controlled asthma according to the GINA criteria:

- No troublesome symptoms during the day or night

- Needing little or no reliever medication

- Having productive, physically active lives

- Having normal or near normal lung function

- No serious asthma exacerbations/attacks8

Over half the 8,000 participants in REALISE had night-time wakening or had symptoms that interfered with daily activities in the week before the survey. Breathlessness was reported as the symptom with the greatest impact. In the 12 months before the survey, almost a quarter (24%) had to visit an emergency department and 12% had been hospitalised overnight. REALISE also found that 14% of respondents found their inhaler difficult to use – a figure that rose to 23% among those with uncontrolled asthma.7

THE CHALLENGE

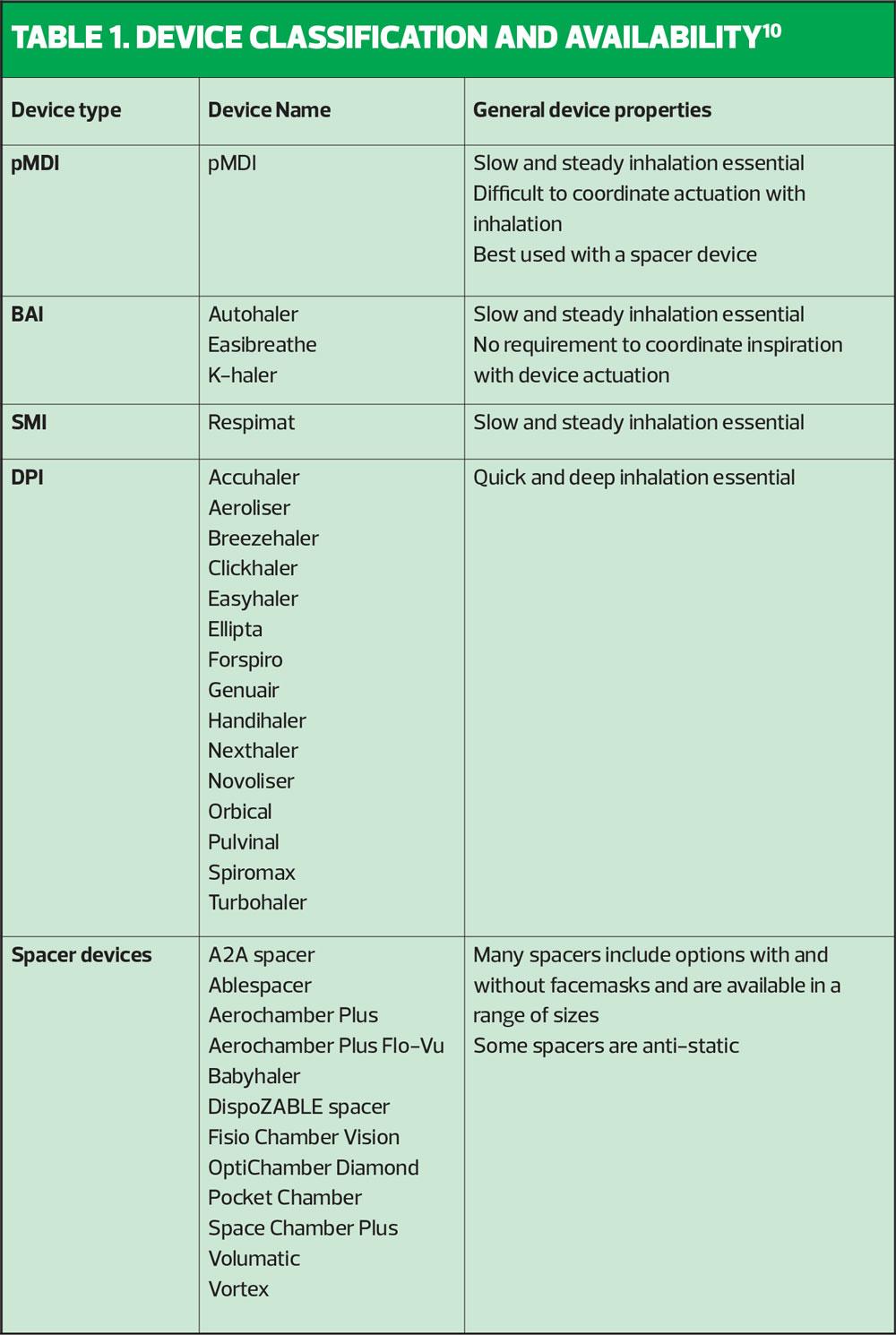

In the UK today, there are at least 20 different inhaler devices in addition to numerous spacers (see Table 1) available for use in the management of asthma and COPD, and with new products coming to market regularly, this number will continue to rise. Furthermore, the range of treatment options available within all of these inhaler devices is vast, and as healthcare professionals aspire to achieve personalised medicine/care for patients, they are increasingly challenged to have good knowledge and understanding of the range of products. Therefore, it makes sense to attempt to classify the devices and the medicines within them because in doing so we can improve our understanding and then apply that to clinical practice. Device selection should be prioritised over product and although not guaranteed, with such a wide range to choose from, should be possible.5

CLASSIFYING INHALER DEVICES

Broadly speaking, all inhaler devices will fall into one of the following categories:

- pressurised Metered Dose Inhaler (pMDI)

- Breath Actuated-aerosol/pressurised Metered Dose Inhaler (BAI)

- Soft Mist Inhaler (SMI)

- Dry Powder Inhaler (DPI)

It is also helpful to understand that pMDI, BAI and SMI are all aerosol inhalers whereas DPI are powder based.

Aerosol inhalers: have a very low internal resistance. The pMDIs and BAIs contain both the medicine and a chemical agent that propels a dose of the medicine when actuated. Because of the low resistance and the chemical propellant, the medication is emitted at speed from the inhaler device. Thus, there is a risk that the medication particles will impact the oropharynx and not reach the airways. Therefore, a ‘slow and steady’ inhalation rate is required to slow the flow of particles and enable them to enter the airways.5

The SMI, while it is an aerosol inhaler like the pMDI and BAI, does not contain a chemical propellant. Instead it relies on mechanical means to produce a ‘soft mist’ of aerosol. This is emitted at a slower speed than that produced by the pMDI and BAI.

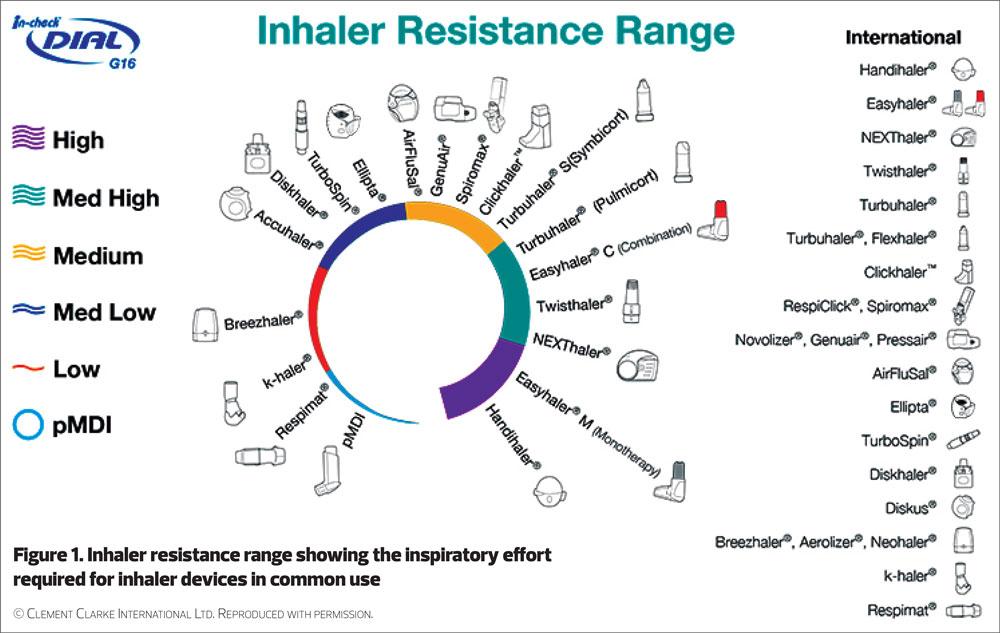

Dry Powder Inhalers: generally have a higher internal resistance. They contain the medicine in a powder format. A ‘quick and deep’ inhalation is needed to break the powder down into fine particles and, to generate the force necessary to draw the particles from the device into the airways. The internal resistance varies between devices and therefore the exact inhalation/inspiratory flow rate required also varies. While a ‘quick and deep’ inhalation is the core principle, if specific detail is needed the patient’s inspiratory flow rate can be measured using an aid such as the In-Check Device.5

Table 1 outlines the range of devices currently available within each classification and highlights some of their general properties. Inhaler resistance for a range of commonly used devices is shown in Figure 1.

Practical tip

Use the table, alongside your local formulary, to help you identify the devices most commonly used where you work. Then try to obtain a set of placebo devices that you can use when teaching patients how to use their inhalers correctly – make sure that your own technique is correct first, see the UK Inhaler Group videos on the Asthma UK website and seek further training if needed.

Pressurised Metered Dose Inhalers

This type of device is currently the one most commonly used in the UK.9 A wide range of medicines is available in the pMDI, which is one of its advantages. Another advantage is that, when used correctly with a spacer device, optimum deposition of the medicine in the airways can be achieved. However, many patients do not use spacer devices (for various reasons) and the pMDI device is difficult to use correctly on its own. Specifically, many patients find the required ‘slow and steady’ inhalation rate a challenge and one-in-four find coordinating the actuation of the dose with the inhalation very difficult.6

Breath-Actuated Metered Dose Inhalers

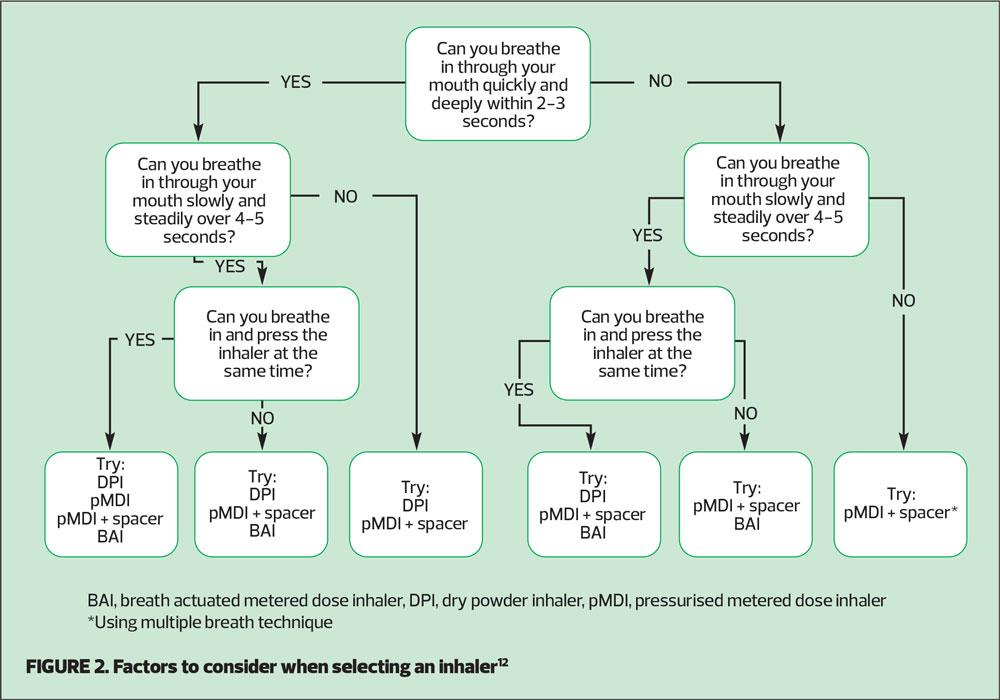

An advantage of this type of device is that most patients find them easy to use: the patient does not need to coordinate their inhalation with actuation, which is a significant benefit for some patients. BAIs have been shown to be simple to teach patients to use correctly, and have good patient preference data.11 The NICE shared decision-making aid on Inhalers for Asthma suggests that if a patient can breathe in steadily over 4-5 seconds a BAI may be a suitable device (Figure 2).12 However, the inhalation rate still needs to be ‘slow and steady’.

Soft Mist Inhalers

A soft mist inhaler, when correctly primed, emits a ‘slow and steady’ fine plume of medication, reducing, but not removing, the need to coordinate actuation with inhalation. The available product range in this device means that it has previously been more commonly used by patients with COPD although its use in asthma is now increasing.

Dry Powder Inhalers

Advantages of DPIs include the fact that there is no need to coordinate inhalation with actuation and there is a wide range of products available in DPI devices.

A disadvantage for some, but not all, patients is that the inhalation rate required for successful deposition of medication in the airways is higher than with aerosol inhalers. One-in-three patients are unable to produce sufficiently forceful inspiration to use a DPI effectively.6

Practical tip

To help you and your patient work out which type of inhaler device may be most suitable, use the NICE Patient Decision Aid, Inhalers for Asthma12(Figure 2)

COMMON INHALER TECHNIQUE ERRORS

In a recent systematic review based on almost 60,000 observations of patient inhaler technique, only 31% of patients were found to be using their inhalers correctly.13

Errors with inhaler technique can be broadly categorised as:

- Not preparing the device correctly

- Not loading the dose correctly

- Not emptying air from the lungs before inhalation

- Not placing the inhaler correctly in the mouth

- Incorrect inhalation/inspiratory flow rate

- Not holding the breath at all or for long enough after inhalation

These common errors currently form the basis for the steps to follow when assessing and teaching patients’ inhaler technique, as set out in the national standards for inhaler technique.

Practical tip

Download a copy of the national standards for inhaler technique4 and use the checklists to guide you when assessing patients’ inhaler technique.

IMPACT OF POOR INHALER TECHNIQUE

Studies show that many, if not most, patients have poor inhaler technique.2,14

It is quite logical to assume that if inhaler technique is poor it will result in less medication reaching the airways thus resulting in poor disease management; poor inhaler technique is associated with poor asthma control and has indeed been identified as a frequent occurrence in patients attending the Emergency Department with an asthma attack.1 However, there are a number of variables that can affect asthma control and cause asthma attacks, and it is difficult to make causal links in every case.

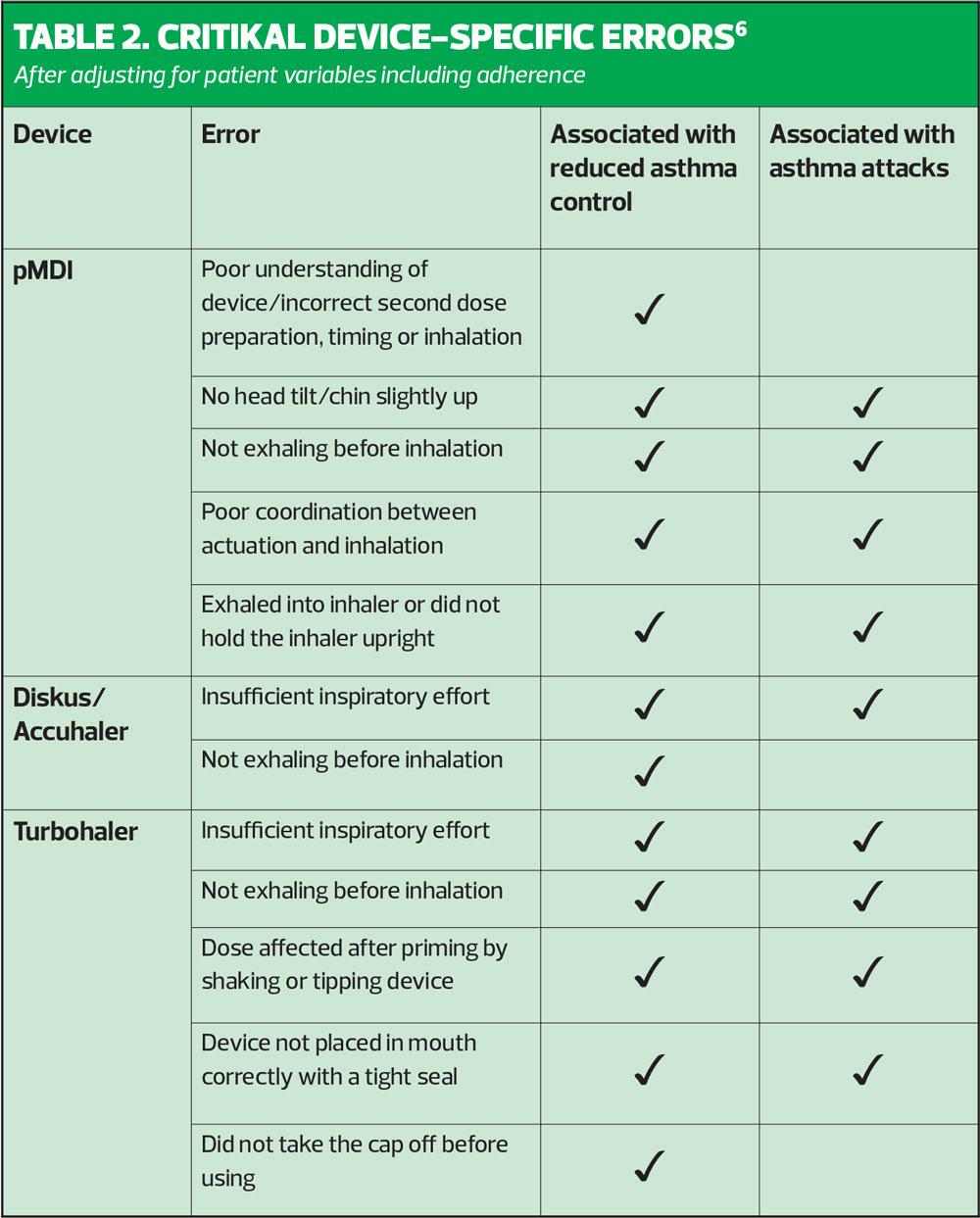

The CRITical Inhaler mistaKes and Asthma controL (CRITIKAL) study aimed to explore the relationship between specific inhaler errors with asthma outcomes such as asthma control and asthma attacks.6 The researchers argue that by identifying the critical errors with each device type, a targeted strategy to improve outcomes for patients could be devised. The success of this strategy, based on the recognition and correction of specific errors with each inhaler type, relies on the skills and ability of the individual clinician, highlighting further the need for quality assured education and training for healthcare professionals. CRITIKAL is a robust piece of research as it was a large study that included 4,276 patients with asthma from eight different countries including the UK. Assessment of inhaler technique was carried out by clinicians who were trained specifically for the purpose of the study, and patient exacerbation rates and levels of control were ascertained via patient questionnaire and from the patient records. The analysis included the following inhaler devices – the Turbohaler, Diskus/Accuhaler and pMDI.

The study found that errors occurred frequently with all devices and that there were errors that were common to all three devices in addition to device specific errors. Among the key findings were that:

- Approximately one-in-three DPI users did not generate sufficient inspiratory effort (dose emission with all DPIs is flow dependent)

- Approximately one-in-four pMDI users were unable to coordinate inhalation with actuation of their device.6

General common errors with all devices included:

- Not emptying air from the lungs before inhalation

- Not holding the breath after inhalation

- Dose preparation errors

The CRITIKAL study adds to the existing body of knowledge because it provides further and specific evidence that poor inhaler technique is linked to poor asthma control and asthma attacks.6 The authors suggest that healthcare professionals will be able to apply this evidence to clinical practice and make changes to the routine management of patients with asthma by identifying inhaler errors and targeting training for patients on the critical errors for their device.6

However, we must remember that to date, we do not have specific evidence for every inhaler device currently available let alone those that may become available in the future, and therefore caution is required when considering the application of this evidence. Application of evidence needs to find a good fit with real world clinical practice and consideration of a number of issues is required. For example, in the UK a wide range of healthcare professionals are involved in the management of respiratory disease but not all are specifically trained or competent in assessing and educating patients about their inhaler technique. Furthermore, given the wide range of devices and treatment options available in addition to the variation in local formulary recommendations, it is difficult for healthcare professionals to offer device-specific targeted training. Therefore, the national standards suggested by the UK Inhaler Group that are based on general principles and encompass all common inhaler errors, seem to provide the most practical and relevant guidance for clinicians in the UK to follow at this time.

CONCLUSION

Inhaler use continues to be an important issue in the management of respiratory disease in the UK. Poor inhaler technique is common and is associated with adverse outcomes including poor asthma control and asthma attacks. Improving inhaler technique relies on healthcare professionals’ ability to recognise and correct errors but to be able to do this with competence, quality assured education and training is needed. Understanding common errors and using general principles for correct inhaler technique supports clinical practice, and the national standards are helpful to healthcare professionals working with patients. Device selection is just as important as drug choice. Breath-actuated inhaler devices are designed to obviate the need for coordinating inspiration with actuation, thus helping to overcome one of the most common errors in technique, and offer an option for patients struggling to use conventional pMDIs or DPIs. The CRITIKAL study has established clear links between specific inhaler devices and poor outcomes in asthma and may provide a foundation for targeted inhaler training in the UK in the future.

Click here to view prescribing information for flutiform and flutiform k-haler

REFERENCES

1. AL-Jahdali H, Ahmed A, AL-Harbi A, et al. Improper inhaler technique is associated with poor asthma control and frequent emergency department visits. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2013;9(1):8

2. Bryant L, Bang C, Chew C, et al. Adequacy of inhaler technique used by people with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Primary Health Care 2013;5(3):191.

3. Westerik J, Carter V, Chrystyn H, et al. Characteristics of patients making serious inhaler errors with a dry powder inhaler and association with asthma-related events in a primary care setting. J Asthma 2016;53(3):321-329.

4. UK Inhaler Group. Inhaler Standards and Competency Document, 2016 https://www.respiratoryfutures.org.uk/media/69774/ukig-inhaler-standards-january-2017.pdf

5. Usmani O, Capstick T, Chowhan H. et al. Inhaler choice guideline: Choosing an appropriate inhaler device for the treatment of adults with asthma or COPD. Guidelines, March 2017 https://www.guidelines.co.uk/respiratory/inhaler-choice-guideline/252870.article

6. Price D, Román-Rodríguez M, McQueen R, et al. Inhaler Errors in the CRITIKAL Study: Type, Frequency, and Association with Asthma Outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;5(4):1071-1081.e9.

7. Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine 2014;24:14009. doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.9

8. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. A Pocket Guide for Health Professionals, Updated 2019.

https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/GINA-2019-main-Pocket-Guide-wms.pdf

9. Lavorini F, Corrigan CJ, Barnes PJ, et al. Retail sales of inhalation devices in European countries: So much for a global policy. Respir Med 2011;105:1099-1103

10. RightBreathe. Rightbreathe.com. 2019 https://www.rightbreathe.com/

11. Bell D, Mansfield L, Lomax M. A randomized, crossover trial evaluating patient handling, preference and ease of use of the fluticasone propionate/formoterol breath-triggered inhaler. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2017;30(6):425-434

12. NICE NG80. Resources: Inhalers for asthma. Patient decision aid. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80/resources/inhalers-for-asthma-patient-decision-aid-pdf-6727144573

13. Sanchis J, Gich I, Pedersen S. Systematic Review of Errors in Inhaler Use. Chest. 2016;150(2):394-406.

14. Lavorini F, Magnan A, Christophe Dubus J, et al. Effect of incorrect use of dry powder inhalers on management of patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med 2008;102(4):593-604.

All websites accessed July 2019

FLUTIFORM is a registered trademark of Jagotec AG, and is used under licence. K-HALER is a registered trade mark of Mundipharma AG.