Inducible Laryngeal Obstruction: not all that wheezes is asthma

Binita Kane

Binita Kane

MBChb, MRCP (Resp), MSc, PhD

Consultant Respiratory Physician, Manchester University Foundation Trust

Stephen J Fowler

BSc MBChB FRCP MD

Senior Lecturer and Honorary Consultant Respiratory Physician, Division of Infection, Immunity and Respiratory Medicine, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust

Jemma Haines

BSc, Reg.MRCSLT

Speech & Language Therapist & NIHR Manchester BRC PhD Fellow

Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, North West Lung Centre, Wythenshawe Hospital

Inducible laryngeal obstruction (ILO) is an under-recognised but treatable condition that can mimic other respiratory conditions, particularly asthma. In this guide for general practice nurses, we discuss how to recognise ILO, its diagnosis and management

Inducible laryngeal obstruction (ILO) presents with breathlessness caused by excessive closure of the laryngeal airway in the neck. The term replaces the previously-used ‘Vocal Cord Dysfunction’, and recognises that the condition is typically initiated by one or more specific triggers, and can also affect parts of the larynx other than simply the vocal cords. It is often misdiagnosed as asthma, but unlike asthma it causes symptoms around the throat, and the most common form is associated with difficulty breathing in (rather than out). It can however also coexist with asthma (and other medical conditions), and therefore presents a significant diagnostic challenge.

CASE STUDY

LK was referred to the regional severe asthma service in August of 2016. She is a 31-year-old mother of three who worked part-time as an administrator. She had been diagnosed with asthma as a child, but her symptoms had been well-controlled until the age of 27, when she underwent a surgical procedure that involved instrumentation of her airway. After this, she started to develop frequent acute episodes of breathlessness, which were diagnosed as ‘asthma attacks’ and led to hospital attendances on three occasions in 12 months. Her asthma treatment escalated very quickly along the steps recommended by the British Thoracic Society / Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network,1 from inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) only to high dose ICS/long acting beta agonist (LABA), followed by the addition of a leukotriene receptor antagonist (montelukast), and theophylline. Meanwhile she continued to require frequent bursts of oral steroids, hence the appropriate referral to the specialist asthma clinic.

On assessment, LK described two types of symptoms:

1. Intermittent wheeze occurring once or twice a week, which responded to inhaled salbutamol

2. Frequent and severe ‘attacks’ which were brought on by identifiable triggers such as aerosol sprays, strong smells, laughter and emotion.

During these episodes she reported she was unable to ‘get any air in’ and would develop noisy breathing. On careful questioning, these sounds were reported on inspiration, and she would have an associated sensation of a tight band around her throat. She underwent laryngoscopy which confirmed ILO. Over the course of several sessions of speech and language therapy the acute attacks resolved completely. LK continued on ICS/LABA but montelukast and theophylline were stopped. She now has well-controlled asthma symptoms without any requirement for oral steroids.

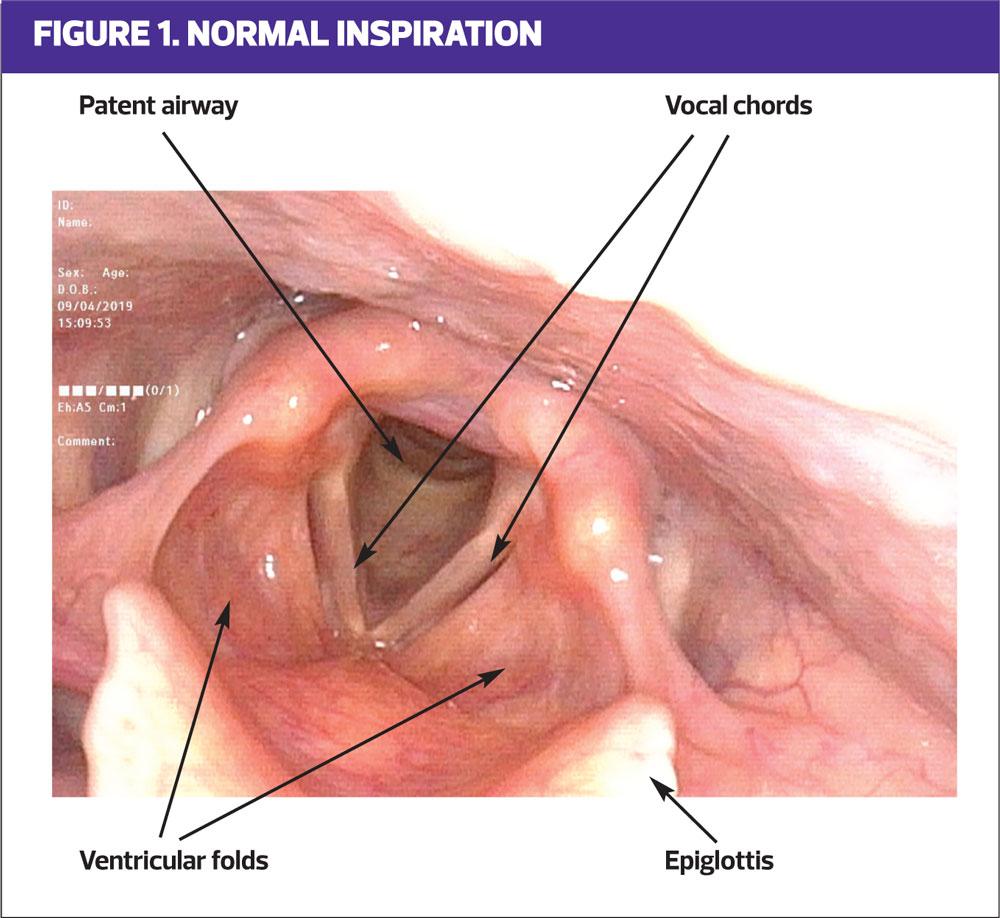

LARYNGEAL ANATOMY AND FUNCTION

The larynx, sited at the top of the trachea, is a structure consisting of cartilaginous, bony and membranous components covered by mucous membrane. Its primary function is to protect the airway; when foreign bodies enter the upper airway the larynx facilitates clearance through throat clearing and coughing. During swallowing it rises and shuts to block the trachea and direct food and fluid into the oesophagus. Its secondary function is phonation, where the vocal cords vibrate when expiratory airflow passes through them. During normal respiration the larynx is open to allow the passage of air in and out of the lungs; in healthy infants expiratory adduction of the cords helps regulate breathing mechanics, and minor expiratory closure persists into adulthood.

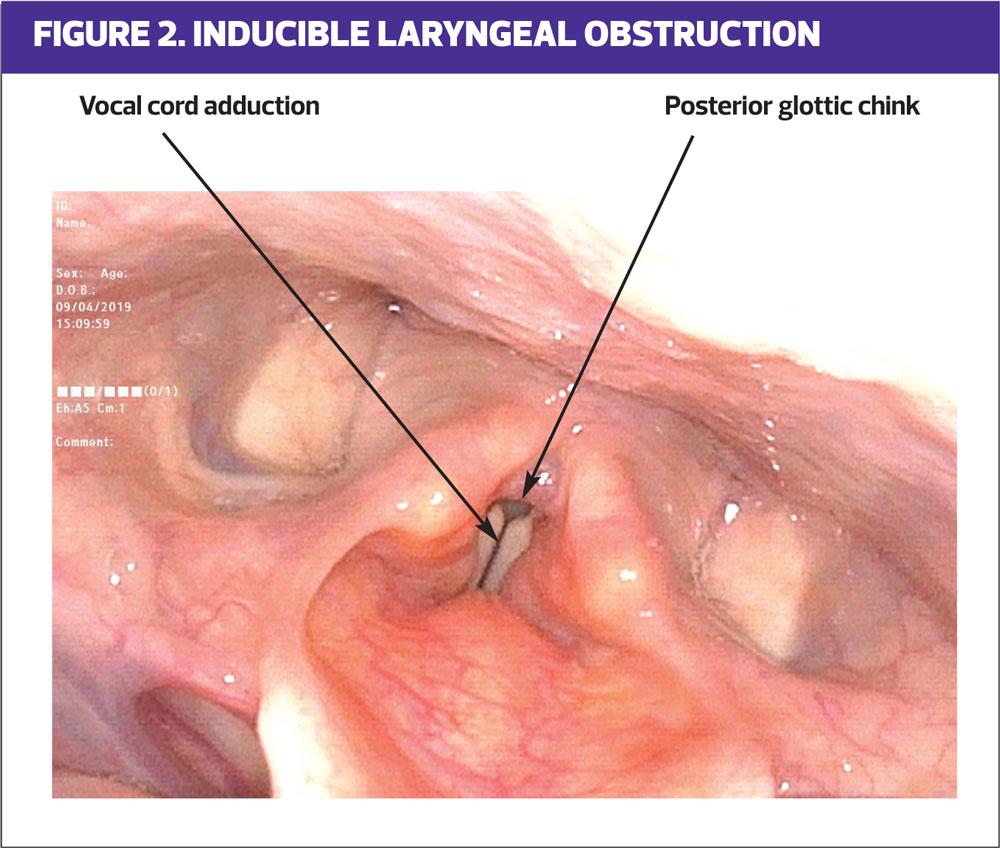

ABNORMAL LARYNGEAL FUNCTION

In ILO, abnormal laryngeal function manifests as excessive closure of the larynx, most commonly during inspiration, obstructing the passage of air and causing individuals to experience breathing difficulties. Classically, symptoms occur suddenly following exposure to a trigger and are usually transient. Key symptoms include:

- Difficulty breathing

- Noisy breathing

- Cough

- Throat tightness, and

- Voice change.2

Historically, abnormal laryngeal closure has been referred to using many terms, most commonly ‘Vocal Cord Dysfunction’.3 Such variation in terminology has caused confusion for the understanding of airway mechanics, as well as for the assessment and treatment of the condition. A recent consensus publication from the European Respiratory Society, European Laryngological Society and the American College of Chest Physicians recommend the term ‘Inducible Laryngeal Obstruction.’4 This describes inappropriate laryngeal closure during respiration, with airflow obstruction occurring at the level of the vocal cords, leading to breathing problems.

As described above, in health the larynx stays open during respiration, with slight movement towards the midline during expiration. Excessive closure in ILO can occur during either or both of these phases. ‘Classical’ ILO, which fits most closely with what was previously described as vocal cord dysfunction, occurs during inspiration, and is therefore associated with difficulty breathing in and noisy stridor. In severe cases, closure can occur throughout respiration. In our experience, isolated ‘expiratory’ ILO is most often seen in patients with obstructive lung disease, typically COPD or severe asthma, and sometimes with obesity or breathing pattern disorder. In these situations treatment should be directed at the underlying disease process. Indeed, directly relieving expiratory laryngeal obstruction could potentially make symptoms of breathlessness worse, as the closure may help support respiration (as it does in babies) by providing pressure-support to the lower airways, and thus preventing them from collapsing.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Speech and language therapy (SLT) is the treatment of choice. The basic principle of treatment is to facilitate laryngeal airway control. Specific therapy exercises, education, irritation reduction and psycho-educational counselling are the common approaches used to achieve control. Treatment is typically delivered over a few sessions and a combination methodology of the various approaches is usually required for best outcome. However, despite SLT being identified as the go-to treatment for ILO, to date no randomised control trial exists and research supporting it as a gold standard treatment is in an embryonic stage.

There is significant association between ILO and asthma; ILO can mimic asthma and patients maybe inappropriately diagnosed and treated for asthma. However, ILO and asthma can co-exist, which makes assessment and treatment challenging. Likewise other conditions that may be associated with laryngeal irritation and/or inflammation, in particular gastro-oesophageal/laryngopharyngeal reflux and chronic rhinosinusitis, are commonly found in these patients. Therefore, to ensure a targeted outcome SLT is best delivered in the context of a multi-disciplinary assessment and treatment model. Unfortunately, service provision in the UK is currently limited but, with increased awareness and understanding about the condition, access is improving. There are now several national treatment centres and work is ongoing to improve the availability of specialist services.

Treatment in an emergency, i.e. when an ILO attack has triggered and the individual has escalating symptoms with lessening control, can be challenging. It is essential, before trying ILO management strategies, to ensure that the symptoms are the result of an ILO attack and not of asthma, especially if the individual has known asthma. Relaxed breathing, reducing extrinsic laryngeal musculature tension, sniffing and panting are all recognised, useful techniques to aid reversal of an ILO attack. Heliox, a mixture of helium and oxygen, is less dense than air and therefore, when delivered through a non-rebreathe mask, may ease the sense of upper airway obstruction. It may be used and delivered in secondary care when an individual is struggling to gain control. However, a recent systematic review of the effects of Heliox in ILO produced little evidence supporting its effectiveness.5 In emergency situations, where the attack is not resolving and the patient is thought to be at risk of respiratory failure, then light sedation, under the direct supervision of an anaesthetist who is prepared to intubate if necessary, can help resolve the episode.

CLINICAL PRACTICE POINTS

History-taking is key to raising the suspicion of ILO, but laryngoscopy, when a patient is symptomatic, is the clinical gold standard required for diagnosis. In patients describing frequent sudden ‘asthma attacks’ ask for a detailed description of the attack, or ask the patient to video record it on their phone.

Things to consider in the history

- How quickly do symptoms come on? Bronchospasm occurring in asthma typically develops over minutes or hours, whereas ILO might occur over seconds.

- Which is more difficult – breathing in or breathing out? Although ILO can occur both during inspiration and expiration, from our clinical experience inspiratory ILO is the most common form. Patients reporting more difficulty breathing in warrant further investigation.

- Are there throat symptoms? In ILO it is common for patients to describe symptoms such as a tight band or ‘choking’ sensation, a lump in the throat or problems with their voice.

- Is breathing noisy during attacks? If so ask specifically if this is on inspiration. Inspiratory stridor is a hallmark of ILO.

- Are attacks triggered by anything outside the norm, e.g. exposure to aerosols, strong smells, changes in temperature or sudden emotion? If so consider ILO.

If you suspect ILO – what are the next steps?

ILO requires specialist assessment by a team experienced in managing the condition. Refer to the nearest Specialist Severe Asthma or Upper Airways Service.

SUMMARY

The long-term management of respiratory disease is now largely undertaken in primary care settings by nurses. With appropriate training, experience and support, nurses can become expert in the management of specific conditions, such as asthma and COPD it is vital that they remember that not all that wheezes is asthma – or COPD.

ILO is under-recognised and many patients with this condition will have suffered continuing symptoms and/or had inappropriate, high doses of therapy, such as repeated courses of oral steroids, with potentially harmful consequences.

It is therefore incumbent on those of us who take on extended roles in general practice to keep an open mind and to remain fully aware of our limitations. If any person we are treating is not responding as we expect or is suffering symptoms despite taking adequate therapy appropriately, we need to seek advice and refer. Whilst a lot of wheezing is asthma, this is not always the case.

REFERENCES

1. BTS/SIGN British Guideline for the management of asthma, 2016, SIGN 153. http://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-153-british-guideline-on-the-management-of-asthma.html

2. Hull JH, Backer V, Gibson PG, Fowler SJ. Laryngeal dysfunction: assessment and management for the clinician. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2016;194(9):1062-72.

3. Christopher KL, Wood RP, Eckert RC, et al. Vocal-cord dysfunction presenting as asthma. New England Journal of Medicine 1983;308(26):1566-70.

4. Halvorsen T, Walsted ES, Bucca C, et al. Inducible laryngeal obstruction: an official joint European Respiratory Society and European Laryngological Society statement. European Respiratory Journal 2017;50(3):1602221.

5. Slinger C, Slinger R, Vyas A, Haines J, Fowler SJ. Heliox for inducible laryngeal obstruction (vocal cord dysfunction): A systematic literature review. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology 2019 Feb DOI: 10.1002/lio2.229

Related articles

View all Articles