Choosing and using inhalers: what's the formula?

Beverley Bostock-Cox

Beverley Bostock-Cox

RGN, MSc, QN

Nurse Practitioner, Mann Cottage Surgery Moreton in Marsh,

Education Lead, Education for Health, Warwick

There is a plethora of treatment options available for asthma and COPD and although choice is usually a good thing, too much choice can make decision making harder – and local formularies can easily become outdated: so how should the correct drug and device be selected?

Most drugs used to treat common respiratory conditions such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are administered via the inhaled route. It goes without saying, then, that careful attention needs to be paid to ensuring that each patient has been individually assessed in order that the most appropriate treatment can be prescribed. This involves making sure that the inhaler is licensed for the condition being treated, has been prescribed at the most appropriate dose using the most suitable molecules and very importantly, that the patient is able to use their inhaler device. Research tells us that many patients are unable to use their inhalers correctly and that healthcare professionals (HCPs) fare no better when assessed.1,2

In this article, which will focus on treating asthma and COPD, key learning points include:

- The importance of being aware of which products are licensed for which condition

- Being able to recognise the main types of inhaler device

- Knowing how to help patients to choose appropriate inhaled therapies

- Understanding new licence indications for established drugs and newer products that are available

- Being able to evaluate the role of formularies in prescribing decisions (including when the GP is the prescriber)

USING INHALED THERAPIES

There is a wide range of drugs used to treat people with asthma and COPD and most of these are delivered through inhaler devices. However, the best drug in the world will be of no use unless it is actually deposited in the lungs. Good technique is multi-faceted and depends upon correct priming of the device, the requisite level of inspiratory flow rate and the use of a breath hold in almost all cases. If the patient has poor inhaler technique, the medication will not be deposited appropriately and its effect will be limited. This increases the chance of people suffering from poor control and may lead to a higher risk of exacerbations or even death.3,4

TYPES OF INHALER DEVICE

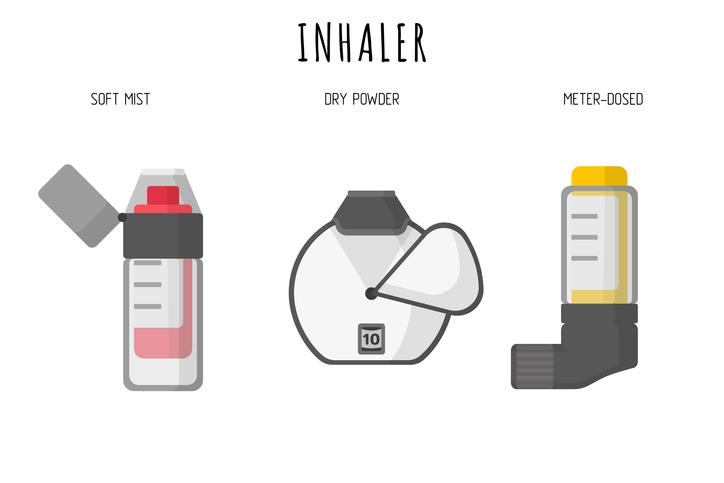

The most commonly prescribed inhaler devices are the pressurised metered dose inhalers (pMDIs) which should normally be used with a spacer device. The other main types are breath actuated inhalers (BAIs) e.g. Easibreathe and Autohaler and dry powder inhalers (DPIs) e.g. Genuair, Turbohaler, Nexthaler and Spiromax. Nurses need to ensure that the most suitable device is identified for each individual based on their age, condition being treated, lifestyle, dexterity and preference. A sound knowledge of the range of available devices is essential and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) specifically states that clinicians should be aware of and familiar with the products that are available in order to tailor treatment effectively.5

CHOOSING INHALER DRUGS AND DEVICES: ASTHMA

Treatment options differ considerably from asthma to COPD and from individual to individual. In asthma, the mainstay of treatment will be inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) i.e. step 2 of the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN) asthma guidelines.6 Many devices deliver ICS therapy so the first step would be to decide whether the patient and the patient’s lifestyle might indicate a preference for a particular type of device from the three on offer. Other considerations might include the range of drugs available in the device so preventers and relievers can be given in the same device and only one type of inhaler technique needs to be mastered. (See Table 1) Another consideration might be that the same device can be used if the individual needs to move up to step 3 of the guidelines and use a combined ICS and long acting B2 agonist (LABA). Other issues which may dictate the device choice will be the existence of a dose counter and any age limitations on the product.

Molecule strength, particle size, onset of action and duration of action (dictating the need for once or twice daily inhalations) will also inform decisions about which treatment to use.

When moving up to step 3, the impact of molecule, particle size, onset of action and duration of action on treatment choice becomes more apparent. Age restrictions are also important to observe.

ASTHMA TREATMENT DECISIONS MADE SIMPLE

Treatment choices in the under 5 age group

The NICE guidelines recommend a pMDI and spacer for younger children.7 However, spacer devices will only work if they are used so it is vital that parents and children understand why they have been prescribed one and why using a pMDI without a spacer may lead to inadequate treatment and may increase the risk of exacerbations and hospitalisation. Optimising drug deposition via the pMDI and spacer may be achieved through the one breath technique or through the tidal breathing approach.8

Treatment choices in older children and adults

The single most important issue is that patients can use the inhaler device. Effective teaching and assessment of inhaler technique by a competent HCP is essential. Check dexterity and any lifestyle considerations.

It is important to be familiar with the range of devices available and to be competent to teach their use. It is sometimes tempting to stick to a few familiar ones but this then restricts the options that might be offered to patients; new devices appear on the market regularly and as mentioned previously, NICE expects clinicians to be aware of the range of drugs and devices available.5 GPNs should offer licensed treatments only and exclude any unlicensed therapies – e.g. those not licensed in the patient’s age group. It is also useful to ask patients if they have any preference for ‘wet spray’ inhalers or dry powder inhalers, to determine any concerns about inhalers with or without a taste and to ask how they feel about spacer devices.

As a result of the availability of once daily options at step 2 and step 3, it is important to ask about any preference for once daily or twice daily inhalers – some prefer once daily for simplicity or because other people help them to take their treatment; others prefer the reassurance of regular twice daily doses and find it easier to remember if they co-ordinate with another activity such as teeth brushing.

Consideration should be given to offering maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) options for suitable patients, e.g. those aged 18 and over who prefer one device for all of their asthma management needs and understand the rationale for MART.

TREATMENT OPTIONS IN COPD

Although similar drugs and devices are available for people with COPD to those used in the treatment of asthma, it is vital to be able to recognise that there are important differences. So, for example, a patient who needs an ICS/LABA combination for their COPD and who prefers to use a pMDI and spacer should only be offered Fostair as there is no other licensed pMDI for COPD. Having patients on other pMDI combinations (remembering that ICS alone is never licensed for COPD) would mean that the treatment was being given off licence. Using off licence treatments is permitted but there needs to be a clear and documented rationale for this decision, the patient should have been informed that they are being treated with an off licence drug and they should have given their consent for this to happen.

FORMULARIES AND DUAL BRONCHODILATORS

A concern with local formularies and COPD treatment algorithms is that they are often based on NICE guidance from 2010.5 However, many clinicians now consider the GOLD guidelines to be more in line with current thinking about how to treat COPD.9 Following GOLD guidelines means that patients may be less likely to be treated with an ICS/LABA for their COPD than when following NICE guidance and may be better off using a LABA, a long acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) or both – the so-called dual bronchodilators. There are four dual bronchodilators each with a different LABA and LAMA and each in a completely different device; three out of four are taken once daily, one (Duaklir – aclidinium and formoterol) is twice daily. As previously mentioned, some patients will prefer the convenience of once daily while others prefer the reassurance of a twice daily ‘top up’. If a formulary did not offer a twice daily option to patients and prescribers, it could be argued that this restricts their choice and could lead to physical and psychological morbidity. Tiotropium has been linked to a lower rate of exacerbations in COPD,10 so the inclusion of Spiolto (tiotropium and olodaterol) could be argued for on the grounds that using it may reduce exacerbation risk and may even be ‘ICS-sparing’ in people who have a tendency to exacerbate but in whom a high dose ICS is best avoided – perhaps due to co-morbidities. The Ellipta device should be considered as it offers the only opportunity to provide those patients that need triple therapy (ICS, LABA and LAMA) all their medication in the same device (Relvar – fluticasone furoate and vilanterol plus Incruse – umeclidinium). Ultibro in the Breezhaler device is the only one which allows patients to load a capsule, inhale and physically see that they have taken all of the drug – something that is very reassuring for some patients. This simple example of why each of the four dual bronchodilators has something unique to offer is used to illustrate how excluding therapies from formularies may restrict access to treatment for certain patient groups and should not be undertaken lightly.

Pharmaceutical companies are constantly working on developing new inhaler devices and updating their licences for those that are already in use. This means that HCPs and patients have a variety of devices and treatments to choose. However, although choice is usually a good thing, it could be argued that too much choice makes decision making harder for all concerned. Local formularies often take national guidelines and develop them to include suggestions about what to use for each stage of treatment but most formularies will also say that they do not replace the clinician’s judgement so general practice nurses (GPNs) need to avoid relying on formularies too much. Some Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) have included unlicensed products on their formularies and others have developed limited formularies with talk of financial penalties for prescribing off-formulary. These practices are ethically dubious, morally abhorrent and legally questionable so again, clinicians should be very wary of following them. Conversely, a well thought through formulary can ensure that evidence based, effective and cost-aware prescribing advice is available to all. A poorly structured formulary will ensure the polar opposite. Nurses who have up to date knowledge about the range of treatments available will be able to differentiate between these two and act accordingly. Ultimately, the decision about what to use should be reached by the patient with the support of their respiratory care team.

A simple explanation of why it is so important for GPNs to support choice and ensure treatment is tailored to the individual is included in the Nursing and Midwifery (NMC) Code of Practice,11 which talks about the importance of the four Ps:

- Prioritise people

- Practise effectively

- Preserve safety and

- Promote professionalism and trust

Later on in this article we will discuss how adherence to the 4 Ps could be breached by following a poorly developed local prescribing formulary.

NEWER DEVICES AND INDICATIONS

Some drugs and devices that have existed for a while have been licensed for new indications in the recent past. For example, tiotropium is now licensed in the Respimat device for asthma at step 4 of the BTS/SIGN guidelines. In December 2015 the NextHaler was licensed for COPD and Fostair also became available in a high strength option (200mcg per puff in both pMDI and NextHaler) for people on step 4 of the asthma guidelines. Although step 4 patients will often be under specialist care GPNs need to be aware of these licences, not least because formulary reviews often fail to keep pace with the rapidly changing arena of respiratory drugs and devices and GPNs may also see these patients.

Newer devices include the Spiromax device for Duoresp. This device bears more than a passing resemblance to the Easibreathe device but has extra features to help with priming the device (including a stronger ‘click’ when loading the dose). It is also a DPI whereas the Easibreathe is a BAI with a ‘wet’ spray. Patients need to be aware of this if they have used an Easibreathe before and are being introduced to the Spiromax device.

An interesting new development in the treatment of COPD is the AirFluSal Forspiro, which contains fluticasone propionate 500mcg with salmeterol 50mcg, the same as the Seretide Accuhaler. Information on the drug and device can be found at www.airflusal.co.uk and the ‘My InhalAR’ app is also available to demonstrate inhaler technique. The device is a DPI which, it is claimed, is easy to use and offers several feedback mechanisms to reassure patients that they have taken the dose. It is also being advertised as being around £8 per month cheaper than Seretide Accuhaler. However, clinicians should be aware of the arguments against using such a high dose of ICS to treat exacerbation risk in people with COPD (increased pneumonia and diabetes risk, for example) when there are other options at lower doses (Fostair, Symbicort and Duoresp) along with an increasing body of evidence for not using inhaled corticosteroids at all in patients at low risk of exacerbations.12,13

THE 4 PS AND RESPIRATORY PRESCRIBING

To return to the issue of the 4 Ps, then, these are examples of when they might apply when treating people with asthma and COPD.

Prioritise people

This means that the most appropriate option for each individual patient is provided, in terms of drug, device, licence and preference and that any decision is patient-focused and tailored to their needs. If all other things are equal, the cost should also be considered. A good formulary will facilitate best practice; a poor one will hinder it and following a poor formulary puts a nurse in breach of the NMC code of conduct. In my opinion, restrictive formularies which prohibit patient choice and deny clinicians the right to prescribe appropriately should be subject to legal challenge.

Practise effectively

Effective practice means knowing the options available, being aware of the evidence base for treatments and treating patients accordingly.

Preserve safety

Incorrect and inappropriate use of any treatment puts patients at risk. Safety concerns should be paramount when prescribing and may include consideration of issues such as ‘Does the use of the inhaler help to maintain the patient’s wellbeing, does it come with the lowest risk of adverse drug reactions and does it reduce the risk of exacerbations, admissions and at worst, death?’

Promote professionalism and trust

Clinicians should always act in the patient’s best interests as they are the patient’s advocate. A professional approach to respiratory care includes being aware of the duty of care owed to each patient. Breaching this duty is the first step towards a charge of negligence. Patients should always be able to trust that their HCP has their best interests at heart.

CONCLUSION

In summary, there is a plethora of therapies available to treat asthma and COPD and new options continue to appear. Although it is challenging trying to keep up with them all, GPNs need to be aware of what is available to ensure that they keep their practice up to date but also so that they can offer the best treatment option for each patient that they see. As well as new options appearing on the market, established therapies continue to evolve with new strengths, device indications and licences for use. Local formularies may help people with inhaler choices but may be out of date in this rapidly changing field and may also be unduly restrictive if developed purely with cost in mind. HCPs should be prepared to identify and challenge poor formulary decisions, especially if financial penalties are threatened for people who do not adhere to these formularies. The risk of breaching the NMC code of conduct by prescribing from a poor formulary is unacceptable. However, in many areas of the country multidisciplinary teams are working together to develop strong, evidence based guidance which supports clinical decision making and facilitates patient focused care without adversely affecting drug budgets. These teams are to be applauded, not least because they show that it can be done.

REFERENCES

1. Virchow JC et al. Importance of inhaler devices in the management of airway disease Respir Med 2008;102:10–19

2. Baverstock M et al. Do healthcare professionals have sufficient knowledge of inhaler techniques in order to educate their patients effectively in their use? Thorax 2010; 65:A117-A118

3. Lavorini F, Magnan A, Dubus JC et al. Effect of incorrect use of dry powder inhalers on management of patients with asthma and COPD Respiratory Medicine 2008;102(4):593-604

4. Royal College of Physicians. National Review of Asthma Deaths: why asthma still kills, 2014. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/why-asthma-still-kills-full-report.pdf

5. NICE CG101. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 2010 www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG101

6. British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN) Asthma guidelines, 2014. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/asthma/btssign-asthma-guideline-2014/

7. NICE TA10. Guidance on the use of inhaler systems (devices) in children under the age of 5 years with chronic asthma, 2000. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta10

8. Asthma UK. Spacers, 2015. https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/inhalers-medicines-treatments/inhalers-and-spacers/spacers/

9. GOLD. Pocket guide to COPD diagnosis, 2016. http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-pocket-guide-to-copd-diagnosis.html

10. Celli BR et al. Effects of tiotropium on exacerbations in patients with COPD with low or high risk of exacerbations: A post-hoc analysis from the 4-year UPLIFT® trial. J COPD F. 2015;2(2):122-130.

11. Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code. Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses and midwives, 2015. http://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/

12. Bostock-Cox B. Masterclass: Using combination inhalers in COPD. Practice Nurse 2014;44(07):13-18. http://www.practicenurse.co.uk/index.php?p1=articles&p2=984

13. Bostock-Cox B. COPD Masterclass: Keeping pace with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Practice Nurse 2015;45(09):19-24. http://www.practicenurse.co.uk/index.php?p1=articles&p2=1195

Related articles

View all Articles