Chest infections: diagnosis and management

KERRY MILLS

KERRY MILLS

RGN

Respiratory Nurse Practitioner, Primary care

Hereford Medical Group

Practice Nurse 2022;52(2:10-14

‘Chest infections’ can encompass anything from bronchitis or pneumonia to an exacerbation of an ongoing respiratory condition – or simply a demand for antibiotics, irrespective of whether the infection is bacterial or viral in origin

The phrase chest infection is often synonymous with a patient’s request for antibiotics, but to clinicians it can mean a lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), an exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), or an episode of acute bronchitis. The terminology can be confusing. Essentially it can be a diagnosis of any of the above, but it is important to gather the history and clinical signs from the patient to establish what treatment and advice is required.

NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries1 topics provide a specific focus on acute bronchitis and community acquired pneumonia, but do not include the other common underlying respiratory conditions. For a patient that has an underlying asthma, bronchiectasis or COPD, CKS recommends that the approach required should be specific to the particular underlying disease. However, there are similarities.

Acute bronchitis occurs due to the inflammation in the airways, following exposure to a pathogen, and can last for 1–3 weeks, although some patients can have symptoms for more than 6 weeks.2

Pneumonia is an infection of the lung in which the alveoli become filled with microorganisms, fluid and inflammatory cells, affecting the function of the lungs and causing increased sputum production (which may be purulent) cough, dyspnoea and hypoxia.3,4 Patients may also become systemically unwell, and present with fever and pleuritic pain. These features account for the clinical signs found on examination.

Both acute bronchitis and pneumonia can be caused by a virus such as such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus or rhinovirus, or by a bacterium such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae or Staphylococcus aureus.

Patients with either acute bronchitis or pneumonia can present with symptoms of a cough, increased sputum production, fever, pain, and general tiredness.2 However, these symptoms will be present to varying degrees of severity. The challenge in both scenarios is to establish how unwell the patient is and how their condition should be treated.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

On first observation of the patient, the clinician can make an initial assessment of the patient’s disease severity. There can be obvious signs of distress – for example, an increased effort to breathe, seen when the patient is using their accessory muscles; or evidence of hypoxia when the patient can appear to have central cyanosis (blueness around the lips), or peripheral cyanosis (blueness in the digits); or signs of confusion or agitation.

It is vital to obtain temperature, pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation, to support the clinical findings. Once the clinician has established that urgent attention is not required, they can proceed to gather a comprehensive history of the symptoms, pattern, and patient concerns.

The supporting information gathered from the patient’s description of onset and nature of their symptoms is key to confirming disease severity and appropriate next steps.

These may include:

- Cough

- Breathlessness

- Sputum production

- Fever

- Tiredness

- Wheeze

- Chest pain

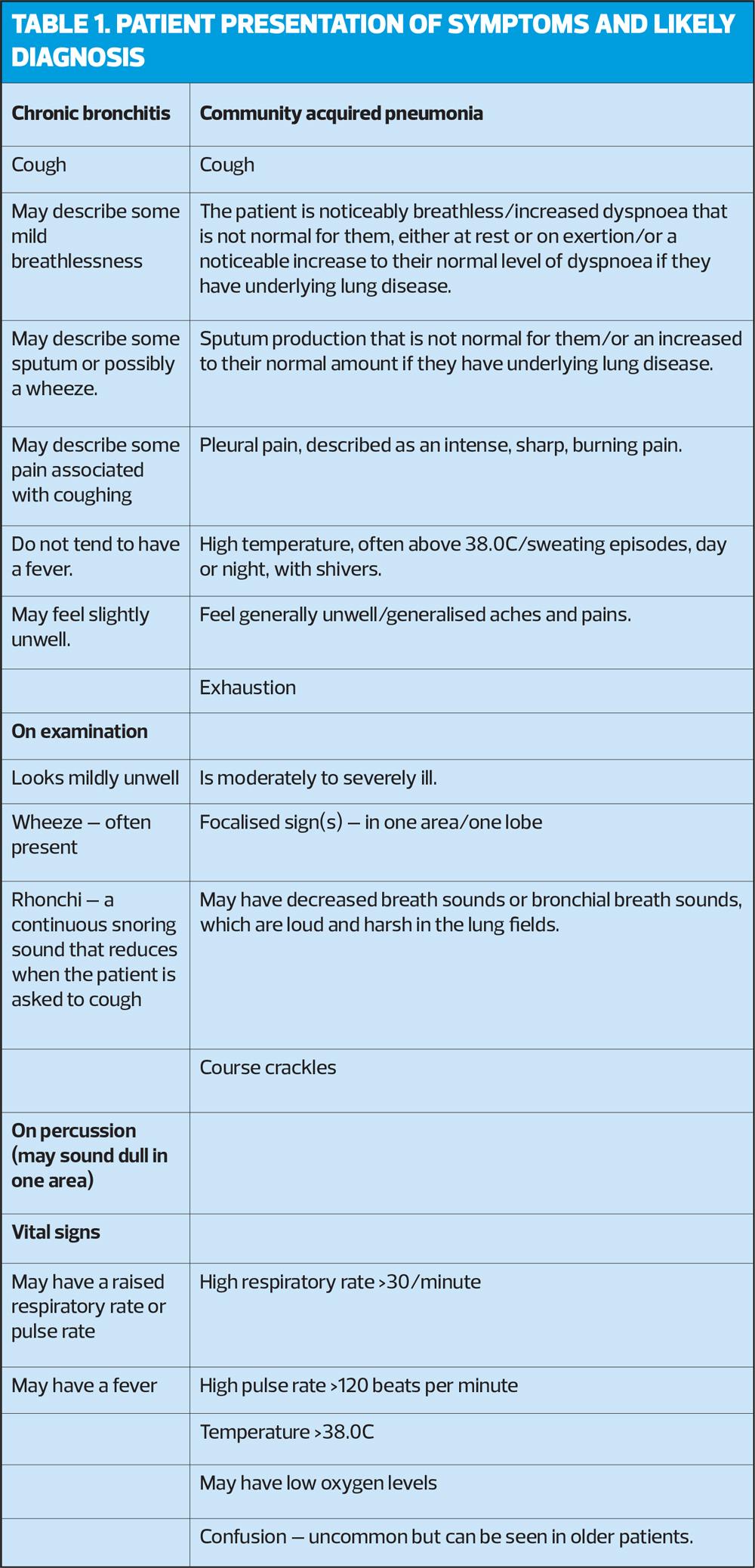

Table 1 provides descriptions to assist with defining the level of severity, helping to indicate which condition is more likely.1

Be aware that patients who present with unusual signs, for example, dry cough, normal temperature, headache, confusion, or diarrhoea, may have an underlying atypical pathogen of pneumonia.1

The elderly patient may present with more subtle symptoms, for example, altered level of consciousness, confusion, gastrointestinal upset, and discomfort. The typical symptoms of cough, fever and difficulty breathing may not be as prominent or may even be absent.1

ASSESSMENT TOOLS

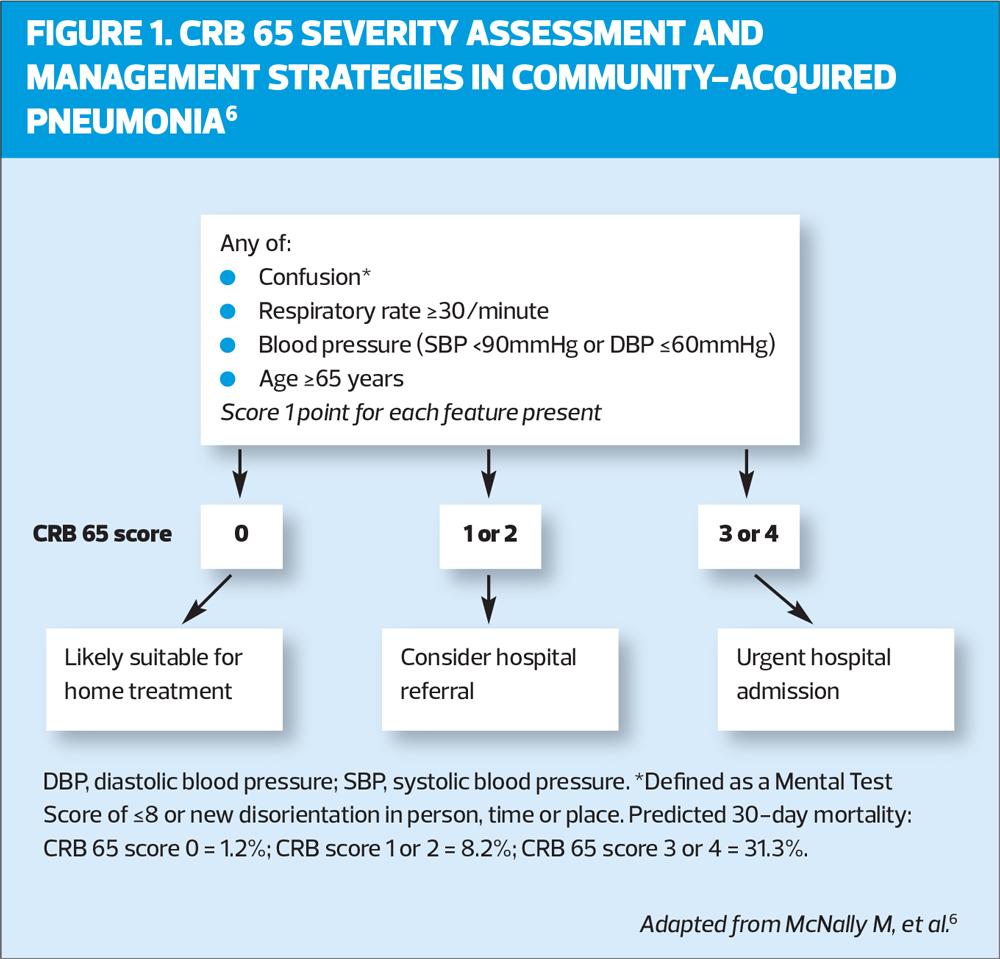

The CRB 65 (Figure 1) is a scoring tool that can be used in the primary care setting,5 which assists the clinician by quantifying the clinical findings and assessment to establish the associated risk to the patient.6 There is a significant risk of mortality in CAP and this tool helps the clinician to measure that risk and act accordingly to improve treatment outcomes.

If the patient presents with symptoms that are suggestive of pneumonia, combine this suspicion with the CRB 65 score.

A systematic review of the application of the CRB 65 tool suggests that it accurately predicts the 30-day mortality in hospitalised patients, but potentially over predicts mortality in community settings.6 However, it is an essential tool to inform decisions regarding whether or not an admission is required and a recognised tool to use when communicating and referring to hospital admission teams.

INVESTIGATIONS

Where there is suspicion of an infection, primary care point of care testing with C-Reactive Protein (CRP POCT) is a simple test that can be undertaken within 5 minutes and can support decisions regarding the appropriateness of antibiotics.7 It measures CRP, which is typically raised as a defensive mechanism to infection or tissue injury. If the CRP is normal, this would indicate the symptoms are not caused by an infective or inflammatory process, thus reducing the need for an antibiotic to treat the patient’s symptoms. It is useful in several scenarios such as:

- Clinical dilemma regarding diagnostic certainty and subsequent management

- Where patients need reassurance that an antibiotic is not appropriate

- Identifying severe illness that requires urgent escalation of treatment.7

Sputum samples can be sent for analysis if there is suspicion of underlying bacterial infection, in moderate severity of CAP in patients being treated at home, or if symptoms persist, but are not routinely recommended in low-severity CAP.8

Chest X-ray (CXR) is not required as a first line investigation in a patient with an acute bronchitis or pneumonia, as the diagnosis is based on clinical grounds.1 However, it is recommended if there is any suspicion of a community-acquired pneumonia, or a high risk of underlying lung pathology, e.g. lung cancer or the cause of symptoms is uncertain.9

Red flags

Patients may present with signs or symptoms that should raise suspicion or concern, warranting urgent action, further exploration, and referral to a more senior clinician, or mentor.10 They include:

- Haemoptysis (coughing up blood)

- Smoker of 45 or over, with a new cough, change in cough, or a hoarseness in the voice

- Prominent breathlessness, particularly at night

- Hoarseness

- Systemic symptoms of fever, weight loss and or night sweats.

- Peripheral oedema and history of weight gain

- Difficulty swallowing

- Vomiting

- Recurrent pneumonia

- Abnormal respiratory test results or examination.

MANAGEMENT

Acute cough

NICE offers specific advice for the management of acute cough, including some ‘Do not do’ recommendations.11

1. Do not offer an antibiotic if there are signs of an upper respiratory tract infection, but the patient is not systemically unwell and they are not at higher risk of complications.

2. Do not routinely give an antibiotic if the patient presents with acute bronchitis symptoms but is not systemically unwell and there is no higher risk of complication.

3. Consider an immediate antibiotic or a backup antibiotic prescription if there is a higher risk of complications, and assess the patient face-to-face.

4. Offer an immediate antibiotic if the patient is systemically unwell at a face-to-face examination.

Patients need to be informed that it is not uncommon for an acute cough to persist for 3-4 weeks, and that it is usually self-limiting; that antibiotics offer no advantage in terms of time to recovery; and that symptoms are frequently caused by a virus, which will not respond to antibiotics. However, they should also be made aware they should seek medical attention if symptoms deteriorate rapidly or significantly, or persist after 3 to 4 weeks.

The NICE guideline does not support the use of an additional mucolytic, oral or inhaled bronchodilator, or oral or inhaled steroids, unless there is another diagnosis that warrants this treatment, e.g. asthma or COPD. Patients should be advised that there is only limited evidence of some benefit for the relief of cough symptoms with over-the-counter cough medicines containing an expectorant (guaifenesin) or a cough suppressant (except for codeine).

COMMUNITY ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA IN THE PATIENT AT HOME

It is important to ascertain who is going to be with the patient at home as they need to be advised to rest and drink plenty fluids to stay hydrated.

Patients who are experiencing any pleuritic pain should be advised to use simple analgesia, e.g. paracetamol, and advised they must seek medical attention if their pain becomes worse.6

The patient should be re-assessed after 48 hours, or sooner if their condition deteriorates. Re-assess the patient’s response to treatment – repeat the examination, baseline observations and the CRB 65 score. Any patient that fails to improve after 48 hours should be considered for hospital admission or CXR.

The evidence recommends empirical use of an antibiotic: amoxicillin remains the preferred option, depending on local guidance.6 If there is evidence of penicillin allergy, clarithromycin is an alternative. Doxycycline can be given as second line if there is evidence of resistance or intolerance. It is essential to ensure the patient is counselled regarding side effects.

The decision to prescribe antibiotics needs to be clearly documented and cover consideration of the severity of the patient’s condition, other comorbidities, local microbiology guidance, recent antibiotic use, and previous sputum samples.6

CASE STUDIES

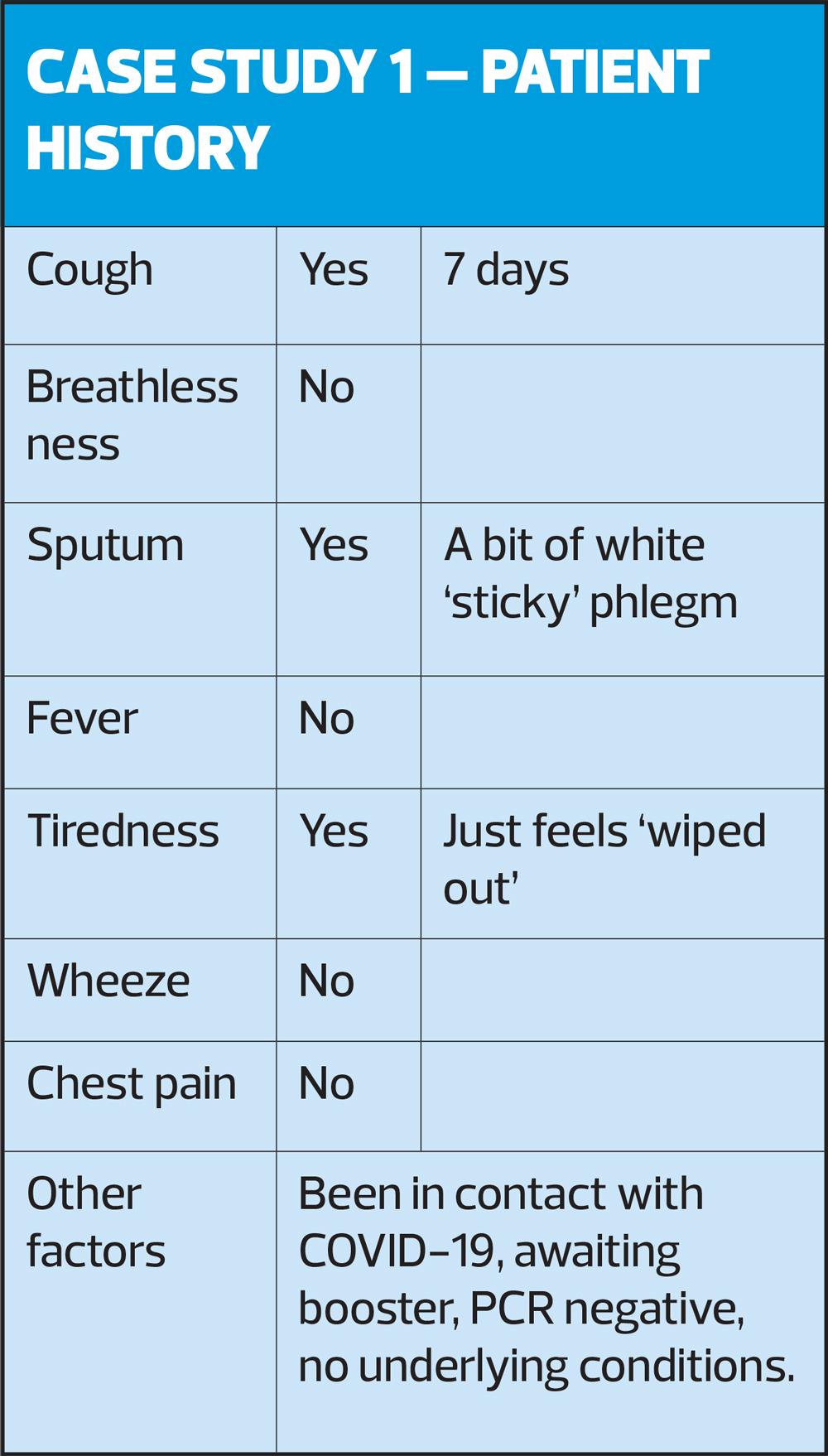

Case study 1 – Gemma

Gemma, aged 26 has rung the surgery on Monday morning requesting a doctor’s appointment for a cough and flu symptoms. When asked, Gemma confirms she had a result of a negative PCR test yesterday via text and it is already documented in her notes. Following the surgery’s acute care protocol, Gemma is added to the telephone list for a call back from the acute care team, on the same day.

Gemma is contacted by the GP.

Assessment: no evidence of cough or breathlessness, speaking in sentences clearly and not confused.

Patient History – see Table

Outcome: Gemma is young and fit, with no previous respiratory condition or comorbidities, with no signs of acute infection ascertained during the telephone consultation, and a short presentation of mild symptoms. The GP discussed how Gemma could support herself at home with self care advice, following the Target infection information.16 This information can be sent via email, text or printed and collected from the surgery.

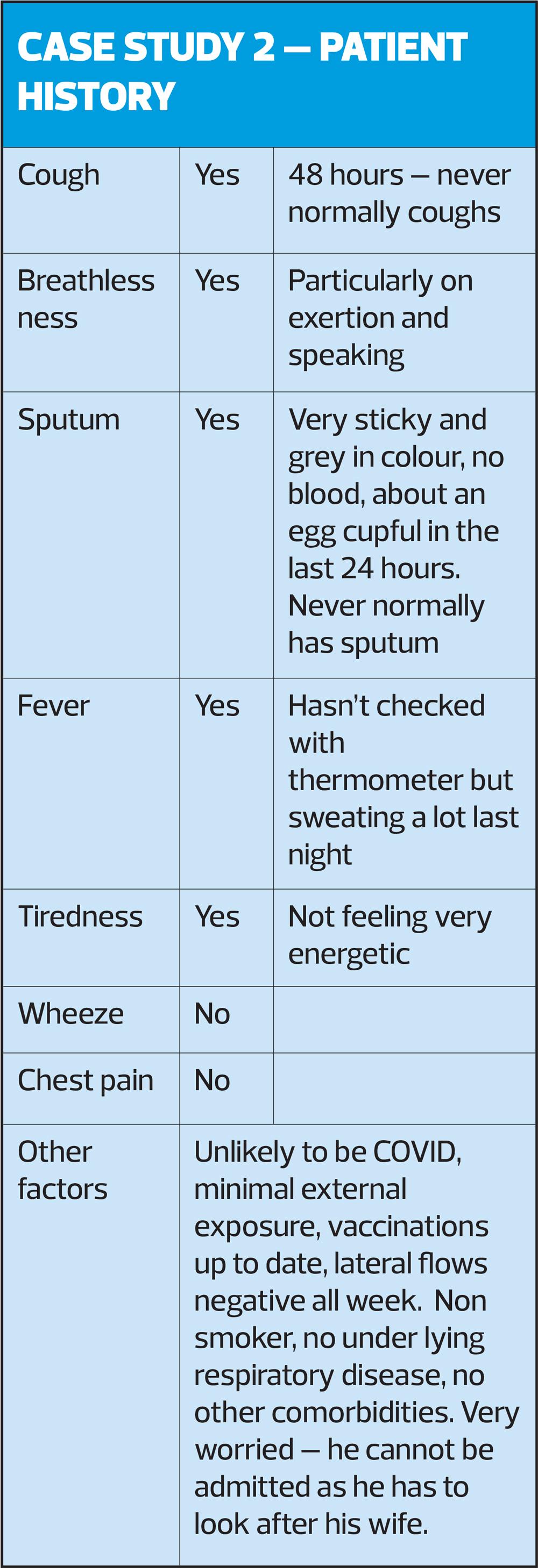

Case study 2

Clive, aged 72, has rung the surgery this morning, because his wife is worried about his ‘awful cough’, he is feeling feverish and coughing up ‘mucky’ sputum. He has been staying at home and has not been exposed to COVID-19, that he is aware of, as his wife completed chemotherapy for lymphoma 3 weeks ago, and both carry out regular lateral flow tests as part of his wife’s treatment regimen. His tests have been negative since the beginning of his symptoms.

Clive is added to the telephone list for a call back from the acute care team, on the same day, and is contacted by the nurse prescriber.

Assessment: wet cough intermittently throughout the telephone consultation, speaking in sentences but obvious breathlessness on speaking. Orientated in time and place. His wife is heard providing a history in the background. An appointment is made for Clive in the ‘Red Clinic’, due to the risk of COVID.

Patient History – see Table

Inspection: Clive walks into the clinic room, unaided, no obvious signs of respiratory distress, speaking in sentences, no signs of cyanosis, intermittent wet cough.

Baseline Observations

Respiratory rate: 19/minute

Pulse rate: 81 beats per minute, no arrhythmia present

Blood pressure: 142/76 mmHg

Oxygen level: 96% at rest on air, no drop on walking and undressing.

Examination: Expansion equal, resonant to percussion throughout, breath sounds reduced right base posteriorly, crackles present right base posteriorly.

CRB 65: 1 (due to age) = Moderate severity7

Outcome: Clive and the NP discuss and agree it is safe for Clive to return home with a 5-day course of antibiotics. This is based upon:

a. Presentation of symptoms is new and within the last 48 hours. Symptoms are not prolonged or persisting despite previous treatment.

b. Clive appears to be clinically stable and systemically well. His baseline observations are within normal range.7

c. He has an adequate support network at home to enable him to rest, maintain good food and fluid intake and will be able to take his medication as prescribed.

d. He has no other high risk contributing factors, such as other comorbidities, underlying lung disease or immunocompromise. He has not used any antibiotics recently and there are no previous sputum samples to guide the prescribing.

Management: Clive is given 5 days of amoxicillin, 1 tablet 3 times a day, in line with local and national guidance. Clive is given strict instructions, with supporting written evidence for him and his family to follow.

Follow up: 48 hours review to ensure symptoms are stabilising.9

SUMMARY

The term chest infection can be confusing, and means different things to patients and to clinicians, but guidance is available to assist with diagnosis and support the clinical decisions that are made. There is also ample evidence and guidance available to support clinicians in making the most appropriate decision regarding the use of antibiotics and how to support patients to care for themselves.

REFERENCES

1. NICE CKS. Chest infections - adult; 2021.

https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/chest-infections-adult/Cks

2. NICE CKS. Acute bronchitis; 2021.

https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/chest-infections-adult/management/acute-bronchitis/

3. Ramirez JA. Community Acquired Pneumonia. Antimicrobe (Infectious Disease & Antimicrobial Agents). http://www.antimicrobe.org/e55.asp

4. Macfarlane JT, Boldy D. Update of BTS pneumonia guidelines: what's new? Thorax 2004;59(5):364–366

5. NICE QS110. Pneumonia in adults. Quality standard; 2016

6. McNally M, Curtain J, O’Brien K, et al. Validity of British Thoracic Society guidance (the CRB-65 rule) for predicting the severity of pneumonia in general practice: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2010; 60 (579): e423-e433 https://bjgp.org/content/60/579/e423

7. Cooke J, Butler C, Hopstaken R, et al. Narrative review of primary care point-of-care testing (POCT) and antibacterial use in respiratory tract infection (RTI)BMJ Open Respiratory Research 2015;2:e000086. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2015-000086

https://bmjopenrespres.bmj.com/content/2/1/e000086

8. British Thoracic Society. 2015 Annotated BTS Guideline for the management of CAP in adults (2009) Summary of recommendations. BTS 2015a.

9. Spanevello A, Beghé B, Visca D, et al. Chronic cough in adults. Eur J Intern Med 2020; 78:8-16

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095362052030114X

10. NICE NG120. Cough (acute): antimicrobial prescribing; 2019.

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng120

11. RCGP. Respiratory tract infection

https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/mod/book/view.php?id=12653

12. NICE CKS. Chest infection: COVID-19 management; 2021.

https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/chest-infections-adult/management/covid-19/