Why digital healthcare must now be usual practice

RACHEL HATFIELD

RACHEL HATFIELD

BA Hons

Programme manager Howbeck Healthcare

ANN HUGHES

RGN

Digital lead Northern Staffordshire technology enabled care services group

DR RUTH CHAMBERS

FRCGP, MD, OBE

Former clinical lead Technology-enabled care services programme, Northern Staffordshire CCGs, Visiting professor Staffordshire University

Practice Nurse 2022;52(8):25-30

The digital transformation of general practice, far from being an IT or new software project, is a change management programme with potential benefits for individual practice nurses, the practice as a whole and for patients

The ‘Ten Point Action Plan for General Practice Nursing’,1 and ‘General Practice Forward View’,2 highlighted the value for nurses of developing their digital prowess. ‘The Topol Review: Preparing the Healthcare Workforce to Deliver the Digital Future’,3 recognised the need for this to be embedded in the NHS Long Term Plan.4 The need for nurses to advance their digital expertise was accelerated when the NHS, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, embraced the biggest digital transformation in its history. Nurses and other clinicians, in all settings, looked to adopt digital opportunities to minimise non-essential face-to-face contact in order to reduce the transmission of infection. Previously, adoption of technology-enabled care (TEC) had been slow and fragmented, sometimes limiting patient choice and sometimes creating unwarranted clinical variation.5

WHAT DOES DIGITAL DELIVERY OF CARE LOOK LIKE IN GENERAL PRACTICE?

‘Digital’ is seen as a key enabler to establishing connected care in Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) in England. It can help deliver more proactive, joined up and seamless care for the population. Digital transformation underpins the national aims for ICSs, which are to:

- Improve population health

- Tackle unequal outcomes and access

- Enhance productivity and value for money

- Help the NHS support broader social and economic development.6

Digitalisation of the NHS, and general practice in particular, is not an IT or new software project, but a change management programme. It has many potential benefits for the practice as a ‘business’, for individual general practice nurses (GPNs) and other team members who realise the advantages of clinical adoption, and for patients and their carers. You do need to have appropriate, up to date IT systems in place in your practice, but everyone in your practice team, as well as your registered patients, also need to adopt the associated behaviour change if digital delivery of healthcare is to be the norm. Nurses in all settings, and GPNs in particular, are well-placed to enable patient participation by ensuring their digital delivery of care is based on a shared-care ethos; e.g. remote monitoring of patients’ long-term conditions (LTCs) by clinicians and redressing of patients’ adverse lifestyle habits.

The adoption and embedding of accessible TEC and digital tools in general practice can deliver potential benefits that include:

- Increased use of video consultation, where appropriate

- Enhanced use of public and closed social media functionality to signpost and support patients with LTCs

- Easy access to self-care information leading to better shared management of LTCs between clinicians and patients

- A consistent, shared approach to TEC and the use of digital tools by all practice team members

- Enabled clinician and patient engagement that increases the likelihood of patient adherence to treatment and redress of any adverse lifestyle habits via behaviour change.

It can also provide a viable approach for more effective and productive working by clinicians.

HOW CONFIDENT ARE YOU ABOUT DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN YOUR PRACTICE?

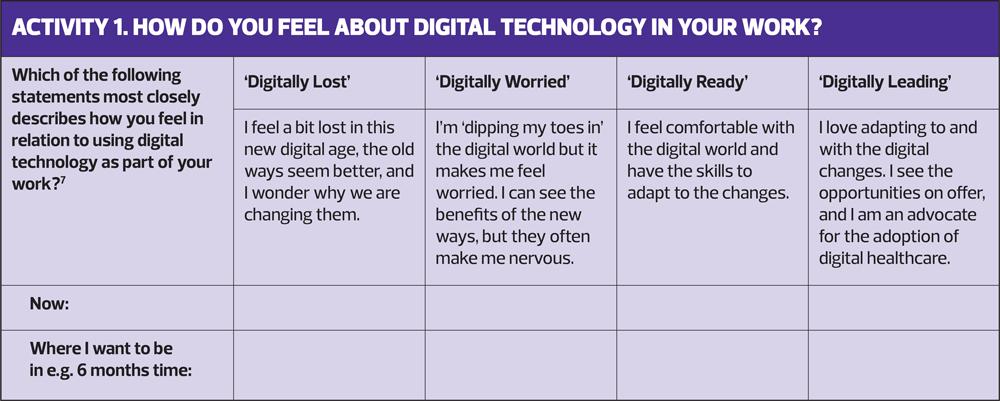

At this point it might be helpful for you to estimate your digital state for adopting TEC in your practice: where are you now and where do you want to be in six months’ time? Activity 1 will help you assess this.

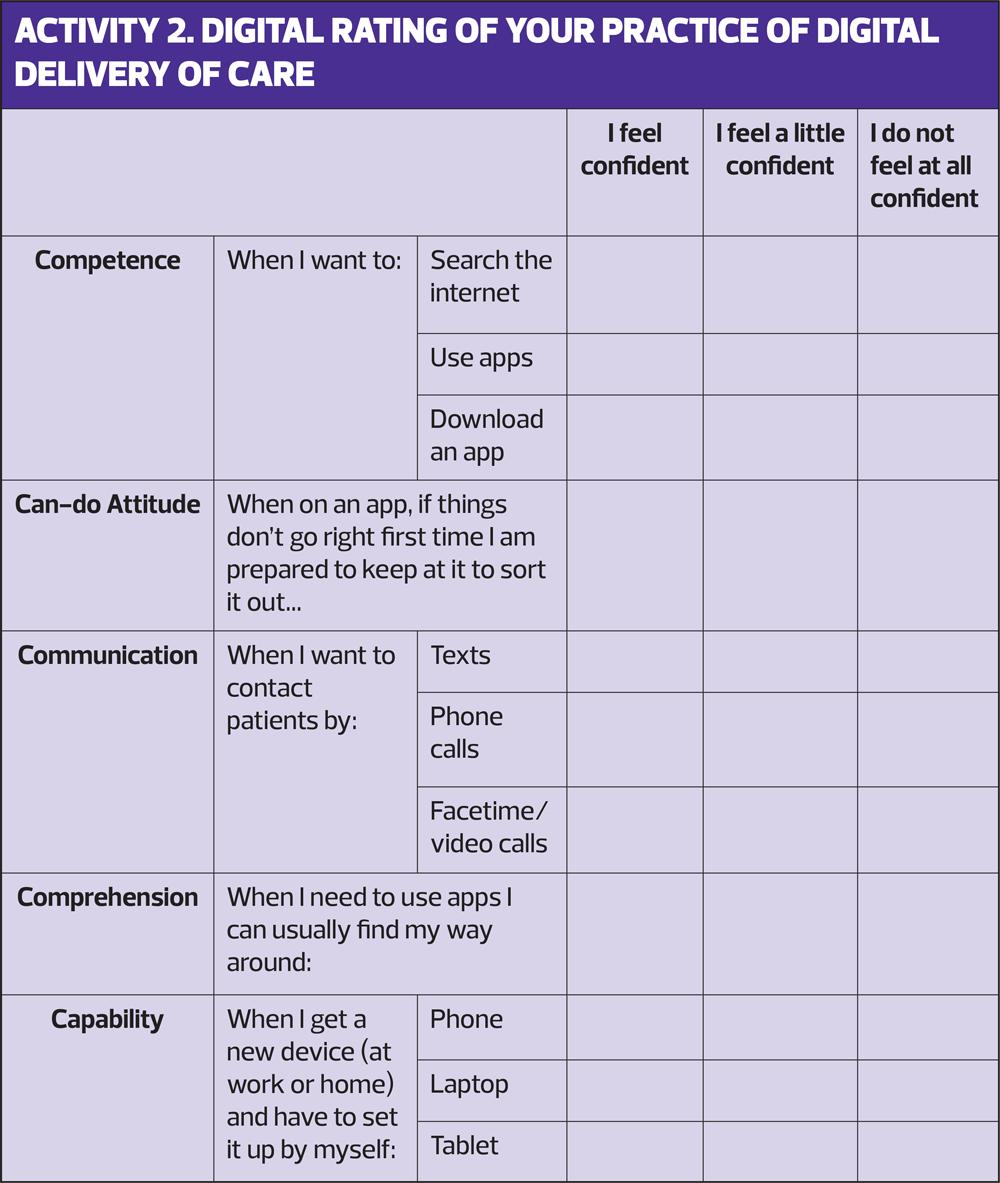

What about your digital literacy? Fill out the table in Activity 2, to rate your confidence and competence in using digital aids for your delivery of healthcare.

BUILDING CONFIDENCE AND COMPETENCE IN DIGITAL CARE DELIVERY: A CASE STUDY

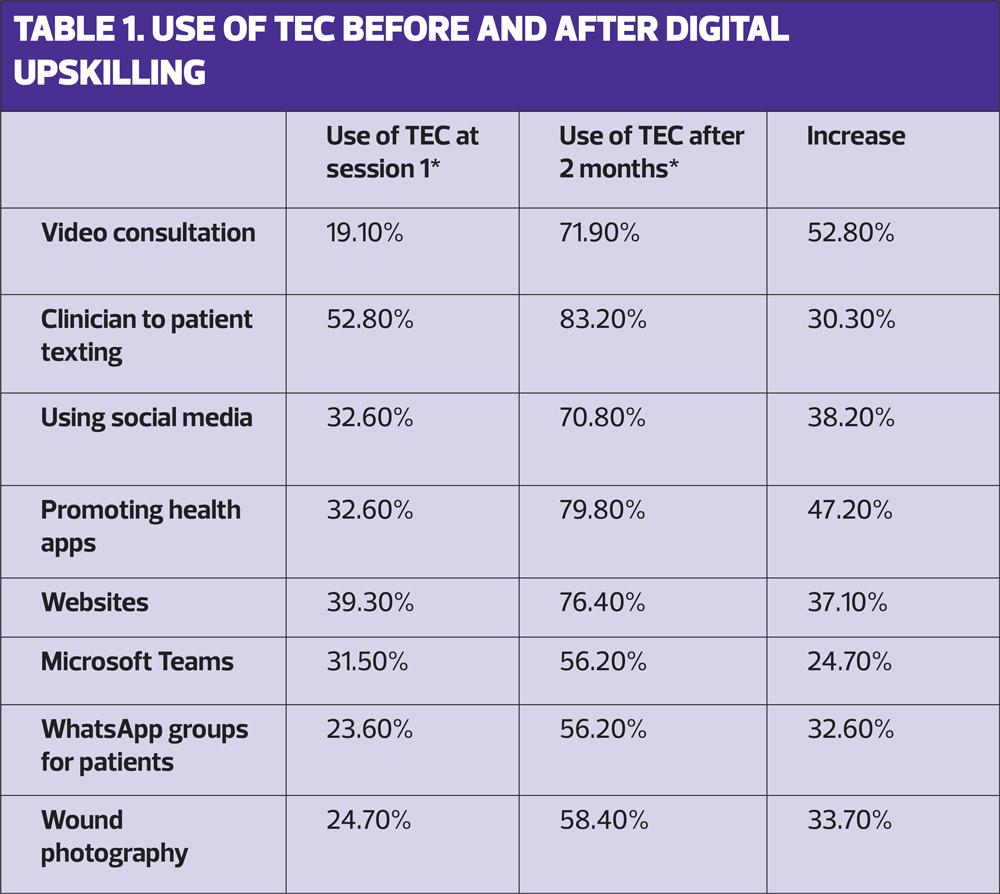

Between June and September 2020 we ran seven, virtual, digital upskilling action learning sets (ALS) across England. We surveyed 89 general practice nurses who had participated in these seven ALS at the start and end of the course.

At the initial ALS session, less than 20% of participants were using video-consultation. By the final session, three months later, 72% reported regularly undertaking video-consultation with patients, and 83% were using clinician-to-patient texting for two-way communication, reducing the need for face-to-face appointments. All participating nurses in the ALSs had advanced the TEC they delivered and digital tools they used, and could see this usage increasing further as digital care became more embedded in their daily work lives. All the participants also felt confident in their ability to share this learning with their wider practice teams, and with other clinicians in their area. They all felt positive about the benefits of introducing TEC/digital tools in healthcare.7 (Table 1)

Participants’ feedback included insights showing that their use of a clinician-to-patient texting service had enabled them to reach more of their patient cohorts. This allowed them to share information in advance of consultations, direct patients to further information etc., which helped to reduce the time patients needed to spend in face-to-face appointments. The use of social media was particularly beneficial for sharing key practice health campaigns, COVID-19 national information and to keep patients updated on any changes to the practice’s access/appointments. Sharing trusted health/lifestyle apps to support patients with key LTCs helped the nurses create a focus on preventive clinical and self-care interventions.

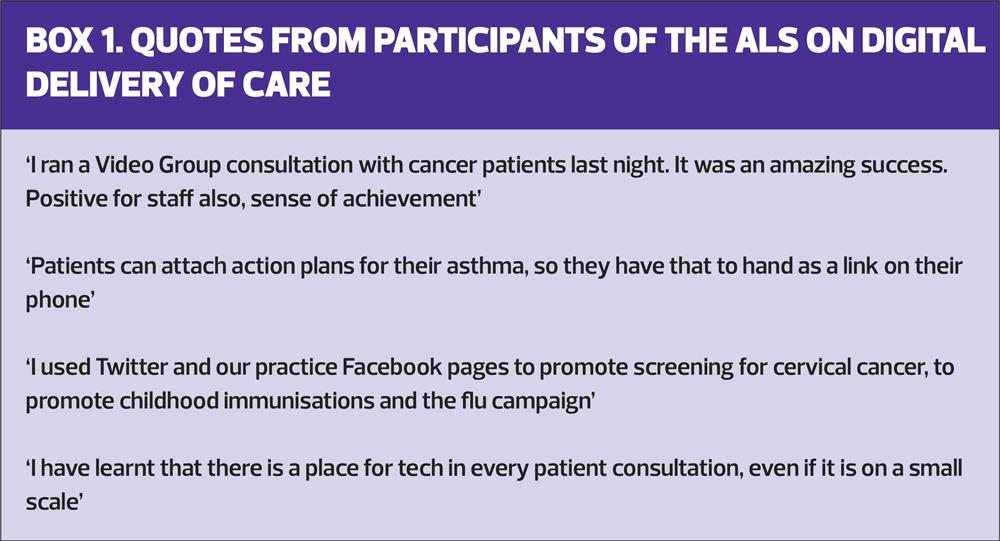

Some quotes from the nurse participants (Box 1) serve to emphasise their appreciation of the benefits of digital delivery of care.

HOW TEC CAN HELP YOU DELIVER DIGITAL CARE

TEC can support LTC management in a number of ways. It can help you make efficiency gains, improve access to appointments and promote educational materials to support patient empowerment, thus enhancing their knowledge, reducing their anxiety and improving communication channels.

Health apps, for people with an LTC such as hypertension, diabetes, frailty or mental health conditions, can be used for preventive actions, such as boosting healthy lifestyle habits. Promotion of the NHS App will enable patients to view their medical records and access other online services.

Social media, e.g. public practice pages for population health messaging, can be helpful. Clinically led, closed WhatsApp groups for patients with specific health conditions, and virtual group consultations can be beneficial for both efficiency gains and widening patient support.

Texting patients detailed information of what to expect, and signposting them to online resources prior to an appointment, can be used to help reduce unnecessary personal contact or delays during the consultation. Automated interactive texting can be used, for example, for feedback of home blood pressure readings and for shared management proactively agreed with the clinician responsible for their care.

Video-consultation can reduce the number of face-to-face consultations and may provide a valuable and sensible substitute for telephone consultations, when this is appropriate.

Signposting patients to trusted website information can give them access to reliable and valid self-care information.

Some of the envisaged improvements that TEC can provide include improvements in patient monitoring. This may be particularly helpful for patients with asthma. Patients could perform peak flow recordings at home, while being observed remotely by the nurse to ensure that the peak flow readings are reliable and recordable. They can also be signposted to videos and apps that reinforce optimum inhaler technique, which could then be observed during a remote consultation.

Other benefits of TEC include:

- Reaching patients in the working-age group who are unable to attend the practice in person due to work commitments

- Monitoring progress when a patient is self-managing wound care

- Supporting patients who are becoming more technologically adept and prefer wider options of consultation

- Improving communication between professionals and patients by using video consultations versus a voice on a phone

- Promotion of health screening and lifestyle information, including animations, via social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram.

- Promotion of webinars relaying educational videos for patients.

WHICH MODES OF DIGITAL DELIVERY MIGHT YOU PRIORITISE?

Video consultations (where appropriate)

Video consultations have been successfully introduced by many practices, with the active engagement of patients across all age groups and demographics. The perceived barrier of age has not been an issue in the majority of cases. Video consultations can be conducted with patients across the age spectrum, for example, from those 90+ who have an asthma review, to a mum doing the glass test on a rash on her young child, where a clinician is able to observe if the rash blanches by using cameras in real time. In this case, the use of video consultation allows instant clinical decisions to be made, and, if necessary, referrals to other providers.

Video consultation can be useful when a patient requires a language translator. If a family member can help, and this is acceptable to the patient, a two-way video call (the clinician and the patient with their family translator alongside) allows a successful consultation, which saves time and is efficient for everyone involved.

Video consultation can be particularly useful for palliative care checks. A video call can allow the clinician to engage as required without intrusion into a family home.

Interactive texting

Clinician-to-patient texting is linked directly with practice systems and patient records. The AccuRx system, for example, populates information straight into the record, and links with other digital platforms (such as sending links to apps or signposting to relevant health and care information). This ability to communicate links to suitable apps and websites allows information to be shared by the clinician in advance of a consultation. Patients are then better informed in advance, some questions will already have been answered via this platform and further information can be accessed as required. This can help reduce consultation time.

Social media

Public social media channels can be used to share information about the practice – opening hours or new procedures, for example, as well as sharing health campaigns and population health messaging. Social media can allow practices to stay in touch with their patient population. During the pandemic social media proved particularly useful as it allowed the rapid sharing of updates with patients.

ANALYSE YOUR PRACTICE’S APPROACH TO DIGITAL HEALTHCARE

At this point it will be helpful to undertake a further bit of reflection.

Look at the general ethos of the practice team.

- Do they regard the establishment of digital healthcare as a ‘must do’?

- Are staff up to date in using the digital options that are available and accessible in the practice?

- Do you have protocols for the delivery of digital healthcare and if so, do staff adhere to the protocols consistently?

You can undertake a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis of your own performance or that of your team, completing this on your own or with a group of colleagues.9 Brainstorm the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats of adopting digital delivery of care as an essential element in your practice.

The strengths and weaknesses of individual practitioners might include their knowledge, experience and expertise. Consider their decision-making, communication skills and inter-professional relationships. Look at their timekeeping and organisational skills, their teaching and evaluation skills. The strengths and weaknesses of the practice team might relate to most of these aspects too, as well as to the resources available – staff, skills and structural elements.

Opportunities might relate to unexploited potential strengths, expected changes, and options for development pathways for many LTCs that might usefully be expanded.

Threats will include factors and circumstances that prevent you from achieving your aims for personal, professional and practice development, and implementation of digital delivery of care.

You will need to prioritise the important factors. Draw up goals and a timed action plan to overcome gaps or weaknesses and make the most of the opportunities. Identify the internal control factors (strengths and weaknesses) and the external control factors (opportunities and threats) that influence you or your practice’s ability to achieve the aims and objectives.

IMPROVING EFFICIENCY AND PRODUCTIVITY WITH DIGITAL HEALTHCARE

The COVID-19 pandemic produced an unprecedented need to advance the use of technology. The NHS needed to urgently look to digital opportunities to minimise non-essential, face-to-face contact in order to reduce virus transmission, both during and after the pandemic.

The 2019 NHS Long Term Plan4 highlighted the need to address efficiency within healthcare by:

- Reducing unnecessary face-to-face appointments to support information sharing that could be dealt with via email and text, thus freeing up appointments

- The sharing of information outside the consultation in order to free up more time in the face-to-face sessions to support patient education and self/shared-care; the adoption of a more motivational interviewing approach

- Enabling patients to access appointments without taking time off work; potentially reducing non-attendance when patients feel well and supporting preventative care approaches

- Enabling patients to have easy access to information via trusted, reliable, appropriate and useful online resources.

These productivity improvements should not be at the expense of creating health inequalities and potential digital exclusion. Many of these elements, however, are outside the remit or control of a general practice. Patients might have problems with poor connectivity, especially in rural areas.

This could potentially lead to longer, fragmented consultations. And we must not forget that some patients may lack the digital skills, equipment or assurance to use online resources, like the NHS App, for ordering medication or booking appointments online. There needs to be a sensible balance between remote and face-to-face consultations, so that patient choice is maintained and a positive patient experience is delivered.10

SUMMARY

The Health and Care Act 2022,11 introduces significant reforms to the organisation and delivery of health and care services in England, with the formalisation of ICSs. True digital transformation of care, however, will only be realised with strong clinical leadership and a culture shift in the way we deliver care as a real partnership between patient and clinician.

With their hands-on, day-to-day practice and clinical responsibilities for preventing and managing patient’s health conditions, GPNs are well placed to lead their practices towards digital delivery of healthcare. They can have a key role in promoting the shared care ethos that TEC can support.

REFERENCES

1. NHS England. General Practice – Developing Confidence, Capability and Capacity: A Ten Point Action Plan for General Practice Nursing; 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/general-practice-developing-confidence-capability-and-capacity/

2. NHS England. General Practice Forward View; 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/gp/gpfv/

3. Health Education England. The Topol Review: Preparing the Healthcare Workforce to Deliver the Digital Future. 2019 http://topol.hee.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/HEE-Topol-Review-2019.pdf

4. NHS. Long Term Plan 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf

5. Chambers R, Schmid M. Making technology-enabled health care work in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2018; 68 (668): 108-109. DOI:https;//doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X694877

6. NHSE and NHSI. Building strong integrated care systems everywhere: guidance on the ICS people function; 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/B0664-ics-clinical-and-care-professional-leadership.pdf

7. Chambers R, Hatfield R, Shams L. GP teams need the confidence, competence and capability to provide video-consultations. BJGP Life.2020 https://bjgplife.com/2020/10/29/gp-teams-need-the-competence-confidence-and-capability-to-deliver-video-consultations/

8. Chambers R, McKinney R, Schmid M, et al. Digital by choice – becoming a part of a digitally ready general practice team. Primary Health Care 2018;28(7): 22-7. doi: 10.7748/phc.2018.e1502

9. Chambers R, Wakley G, Blenkinsopp A. Supporting self care in primary care. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing; 2006. (Converted to second e-edition by CRC Press, Taylor and Francis; 2018)

10. Nuffield Trust. Getting the best out of remote consulting in general practice; practical challenges and opportunities;2022. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/getting-the-best-out-of-remote-consulting-in-general-practice-practical-challenges-and-policy-opportunities

11. Health and Care Act 2022-UK Parliament-Parliamentary Bills https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3022

Related articles

View all Articles