Patient Unmet Needs (PUNs) and Professional Education Needs (PENs): Using reflective practice to identify your learning needs

Rhian Last

Rhian Last

RGN MAMS PGC (Leadership) UCPPD (Quality Improvement Skills Facilitation) PGC (Primary Care Education)

Nurse Educator

RCGP Yorkshire Faculty Board Member

Self Care Forum Board Member and Trustee

Practice Nurse 2020;50(8):30-35

As healthcare professionals we want to do our best for patients but may sometimes fail to discover what matters to them – patient unmet needs 'PUNs' – and we sometimes fail to identify our professional education needs – 'PENs' – to address them

During our consultations we all strive to do our best for our patients. Nevertheless, we sometimes miss the mark, by not ascertaining what matters to them (their needs) or with shortfalls in our professional practice. We may not always be aware that this has happened and this is a missed opportunity to identify associated needs in our training and education. This article explores that, by taking time to identify our Patient Unmet Needs (PUNs) through reflective practice, we can then ascertain our Professional Education Needs (PENs) in order to improve practice, address patient safety and enhance our patients’ experience.

Case studies are aligned to the format of the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) Reflective Account Proforma.

BACKGROUND

In general practice much of our work can seem essentially task orientated and shaped around the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). When this is compounded by time pressures this can create an impatient culture which can impact on clinical practice. This in turn can compromise patient safety and affect quality of care, two key areas that should be at the heart of everything we undertake.1

Key to counteracting this is to learn how to take a step back and effectively reflect, in order to gain a deeper insight into what is happening, understand what is working well and, importantly, to identify what might be improved in order to better support the needs of our patients.

Patient Unmet Needs (PUNs) can be brought to light at the end of a consultation, after the patient has left the room. Take the time to ask yourself, ‘What could I have done better?’ Once deficiencies have been recognised it then becomes possible to recognise your Professional Education Needs (PENs). Ongoing training and education is fundamental to our continuing professional development, and integral to appraisal and revalidation. However, there can be a tendency to pursue further education solely in topics that are of interest to us (‘comfortable learning’) rather than taking the time to understand what further training and education will benefit us, and facilitate supporting our patients’ needs the most. In other words, learning that can translate into improved practice. There is value in all education but the greatest value will be found in responding to our educational ‘needs’ rather than ‘wants’.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

Reflection is a process, not an outcome. It should therefore become a continual activity,2,3 so that it becomes embedded in day to day professional practice, supporting purposeful personal development and facilitating meaningful and fulfilling appraisal and revalidation experiences.

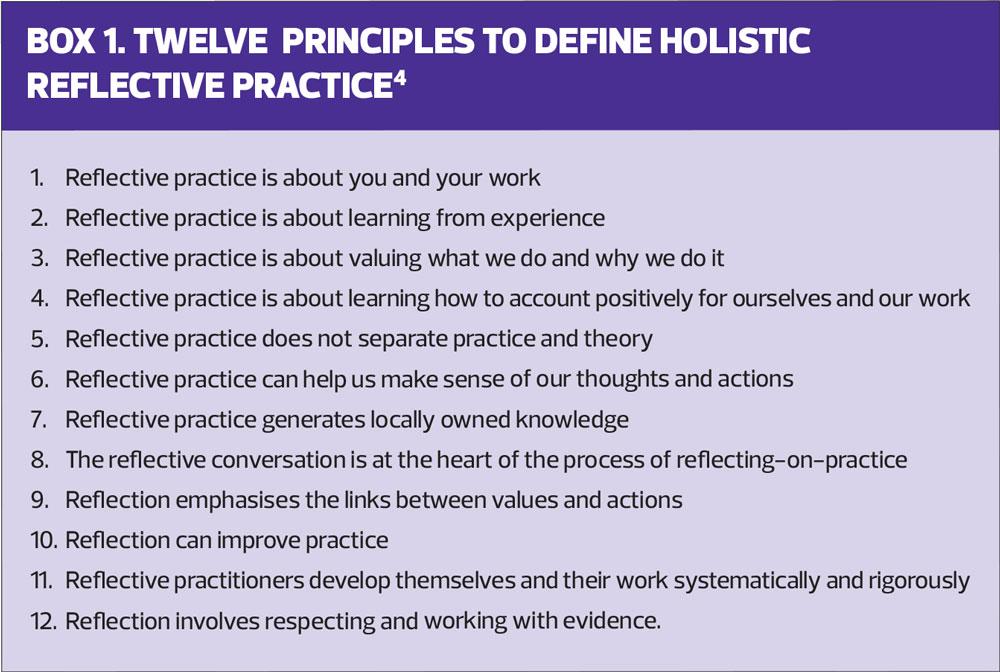

Reflective practice facilitates a heightened awareness of our conduct and behaviour, and the ensuing consequences, in order to learn and improve.3 There is a recognised value in considering reflective practice holistically,4 as defined in the 12 principles listed in Box 1.

There are three forms of reflective practice:

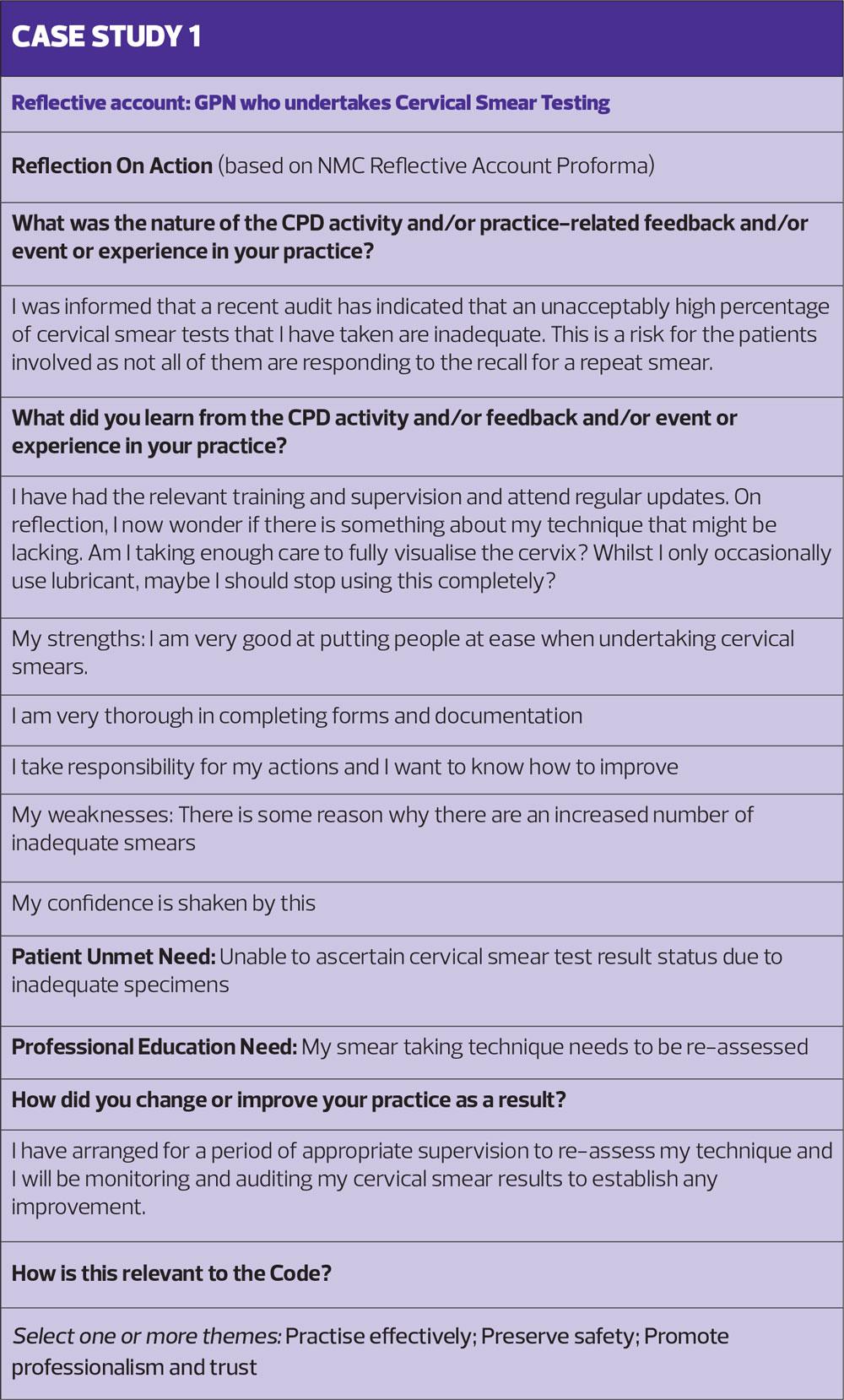

Reflection on Action

This involves reconstructing events at a later stage and using this process to gain an understanding of your own strengths and weaknesses. This helps to identify a way forward that will lead to improvement (Case Study 1).

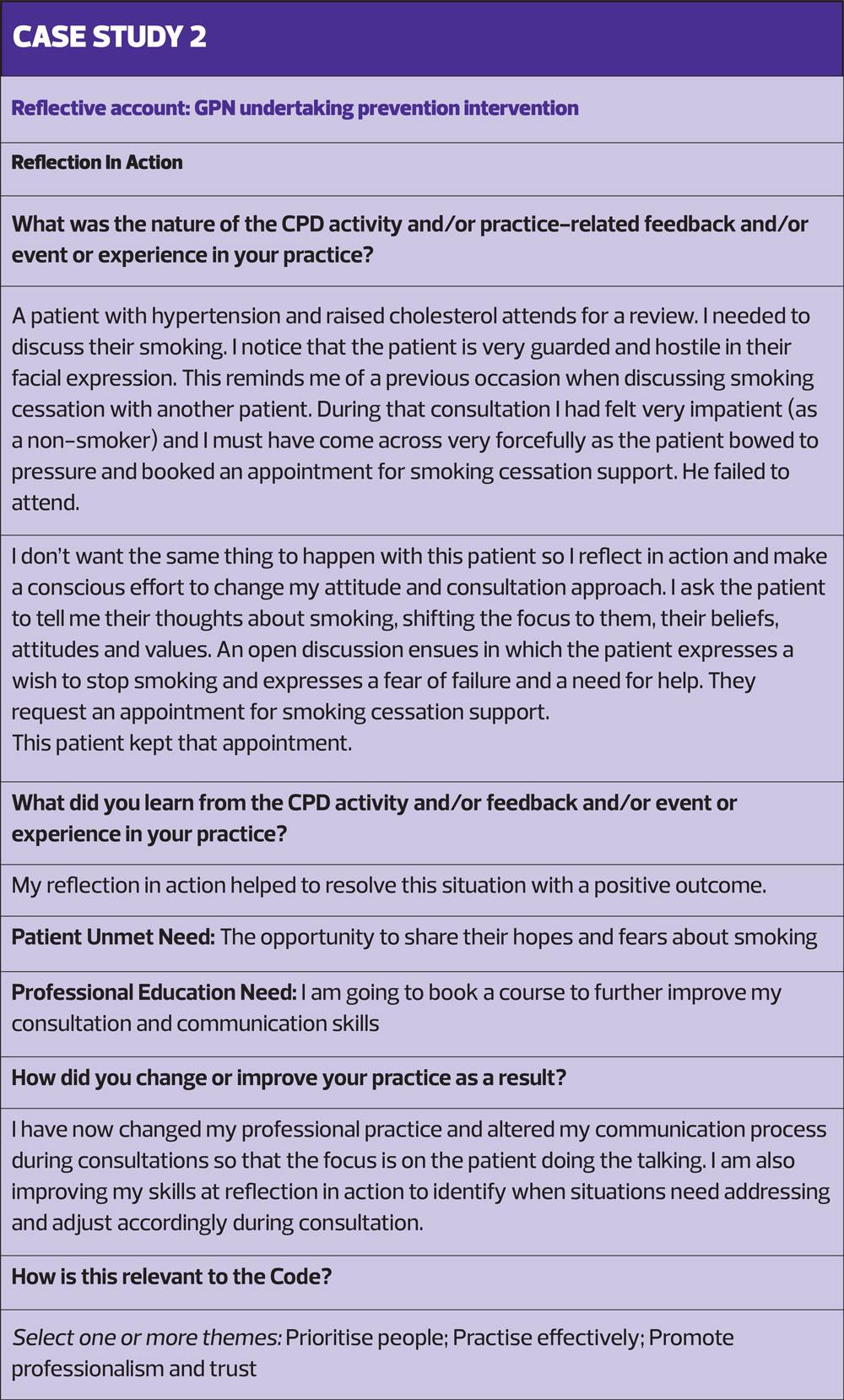

Reflection in Action

This involves considering your behaviour, and that of others, while you are actually in a situation.

To do this effectively you have to be both a participant and an observer, paying close attention to what you are seeing and feeling and being consciously aware of how you are responding. You will make connections with previous experiences and take actions accordingly (Case Study 2).

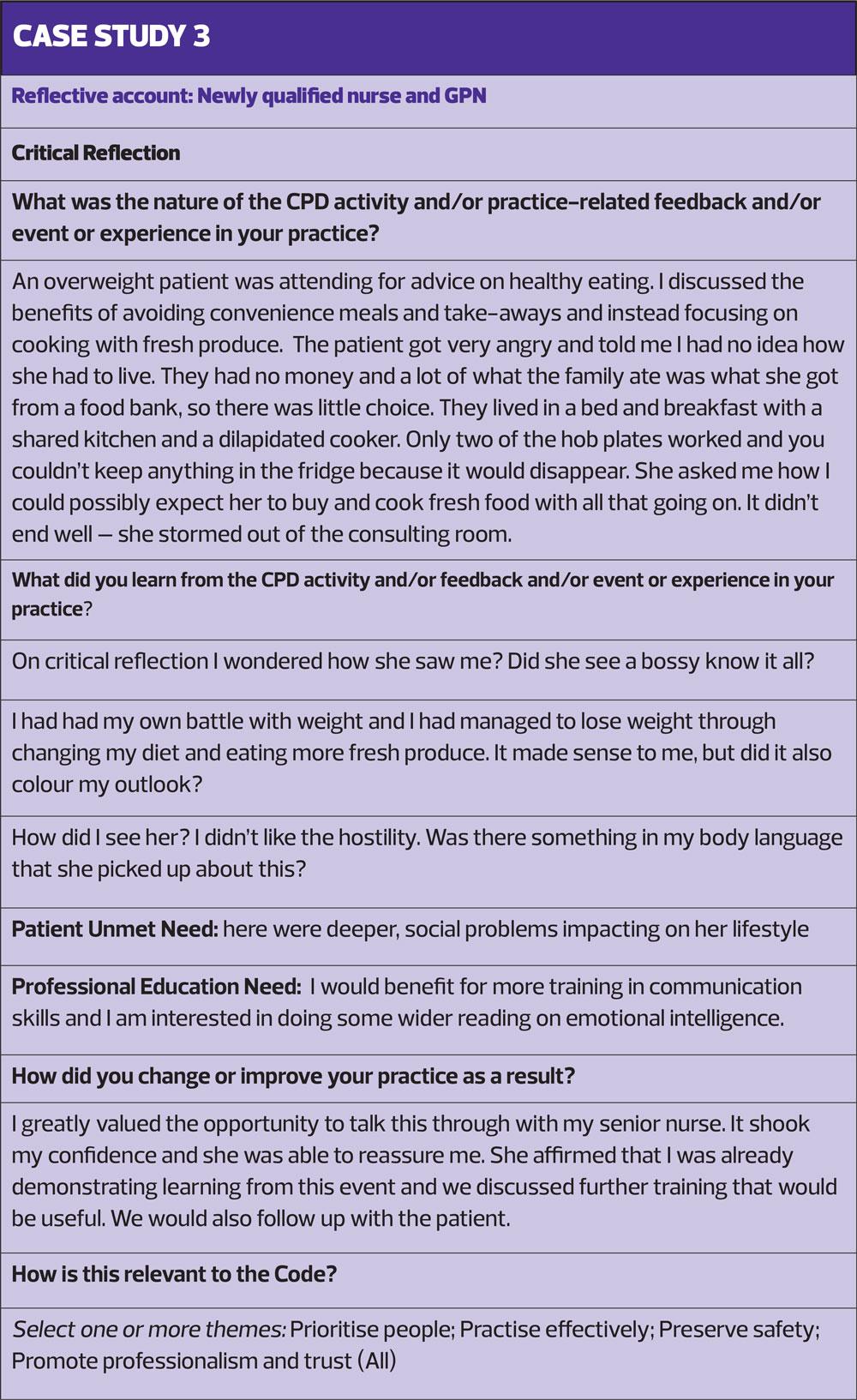

Critical Reflection

This refers to our ability to develop insights into our assumptions about ourselves, other people and our workplace.

Previous experiences will shape our perceptions and help us make sense of the world around us. Our personal experiences constitute and influence our reality. Have you ever noticed how two people’s description of the same event can differ widely? Critical reflection involves examining the assumptions, beliefs and values that contribute to our personal perceptions of the world around us and to speculate about the future and take action (Case Study 3).

Reflective practice facilitates the development of self-awareness and awareness of others, through emotional intelligence, appreciative intelligence and narrative intelligence.

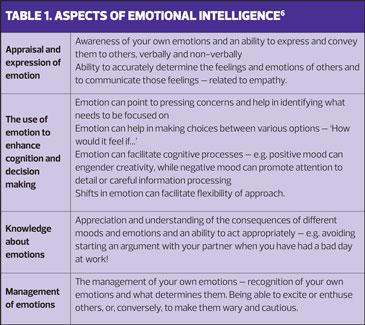

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE

Emotional intelligence involves the ability to understand ourselves and others. Interestingly, the most effective leaders score highly in emotional intelligence.5 With that in mind, we need to think of ourselves as leaders for our patients; servant leaders who ‘do with’ rather than ‘do to’.6 To do this effectively we need to be able to step into someone else’s shoes and see things from their perspective. While such skills can be taught, they tend to come with experience and maturity.

Emotional intelligence can be broken down into four main aspects:7

1. Self-awareness

2. Self-regulation

3. Motivation

4. Social skill (Table 1).

APPRECIATIVE INTELLIGENCE

Appreciative intelligence has been defined as the ability to find the positive in a situation and build on this to drive improvement.

Importantly, this will entail an approach which is a combination of realism and optimism.8 It’s important to ask questions that help to build positive relationships,9 in this case with our patients. It is essential to listen to another person's point of view, never assuming that we can understand their situation. Stephen Covey refers to such assumptions as prescribing our own prescription spectacles for everyone else.10

NARRATIVE INTELLIGENCE

Narrative intelligence is based on the ability to make sense of our practice and learn from it through telling, and listening to stories and dialogue.

The application of narrative intelligence involves harnessing the power of story to improve communication that ultimately can lead to change in practice.11 All too often clinicians fail to listen faithfully to what a patient has to say, thus the advice given can be both aimed at a totally different story and therefore irrelevant and meaningless.12 In order to manage this effectively we need to develop narrative competence – that is to say, the skill of absorbing, interpreting and responding effectively to stories.13

IDENTIFYING YOUR PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION NEEDS FROM REFLECTION

Ask for feedback

This is central to the process of reflection. It should be undertaken with someone you trust to give honest answers, and whose opinion you value. Such a person’s feedback will give you helpful information. There is also added value to widening your perspectives by sharing your reflections with another professional. Indeed it is a requirement of the NMC revalidation process to undertake conversations with your chosen reflective discussion partner. It’s important to make maximum use of this time together in order to gain deeper insights into your learning needs.

Explore what you have learnt

It’s important to adopt a positive approach to lessons learned. This is particularly useful if you have had to deal with an upsetting or difficult situation.

Investigate your strengths

Reflective practice should not be about self-criticism. While it is important to understand what might be improved it is equally important to appreciate what you do well. You can transfer those strengths to areas that require improvement.

Be objective

Learn to look at your behaviour objectively. This will help you become the ‘participant observer’ and develop skills for ‘reflection-in-action’.

Think back to an incident you were involved in and ‘step back’ from it, as if you were observing it from outside. Look carefully at what you were doing and saying, what others were doing and saying and how they were reacting – verbally and non-verbally. Look at the role you were playing in this incident. You may see the incident differently if you look at it from this perspective.

Be empathetic

Try to see, hear and feel how another person may have experienced a situation. This can be particularly helpful when you have been involved in conflict of some kind. It can add new perspectives and insights to your analysis of the experience. Reflect on what this other person might be thinking about how you are thinking or feeling.

Maintain a journal

Writing down or recording your experiences, thoughts and reflections in a private journal can be cathartic! It also need not be time-consuming. It could be as simple as writing down an adjective to describe your day, followed by another adjective to describe how you want the next day to be. Look back the following day. Did the day match your aspirations? If not, why not? Alternatively, you may want to write a brief description of the best and worst aspects of your day. How do you think this may have impacted on your patients and their unmet needs – their PUNS?

The important thing is to write honestly and freely, using the words you want. Your diary is private and is not a test of your grammar, grasp of language or ability to construct a logical piece of writing!

Look for patterns

Another vital aspect of keeping a journal is to look back at it and learn from it. Looking back at your diary after a period of time will help you discover emerging patterns to your thoughts and reflections, or connections between the patterns. What can you learn from the positive connections and patterns and how can you make best use of them? Are there any patterns that worry you, and what can you do about them?

PLANNING YOUR EDUCATION

Once you have made connections, discovered patterns and made sense of your reflections you are in a position to identify your own PENs. And, having identified your PENS, you will be in a position to start making a plan of action. You might wish to apply the SMART acronym:

- Specific – be specific in your aims and expected outcomes

- Measurable – you will find it useful to put some measures in place. This will help you to monitor what is working well with your plan and to make any modifications/adjustments that might be needed.

- Achievable – don’t push too far too soon. Make sure you study at a sensible pace in order to consolidate your learning.

- Reasonable – don’t strive to over achieve but rather engage in learning that will be meaningful and applicable in practice.

- Timely – set a timescale for new learning to be undertaken and completed. This will help to keep you on track.

Identifying your learning style

To improve your learning experience you will find it useful to understand how you like to learn. This is referred to as your preferred learning style.

Fleming has identified four different ways that people prefer to receive information and this is referred to as VARK:14

- Visual – people with a visual preference enjoy learning with images, diagrams and maps.

- Aural – people with an aural preference will benefit from being able to listen, perhaps in face to face training, via a presentation, voice overs etc.

- Reading – people with a preference for reading will gain value from written learning content, books, journals etc.

- Kinaesthetic – people with a kinaesthetic preference are very ‘hands on’ and enjoy interactive learning and activities to complete.

While we can all adapt and learn in different ways we will all have a preferred learning style, a format that we are most comfortable with and which best facilitates our learning. This can also be useful to apply for revision or consolidation of newly acquired knowledge. For example, people with a visual preference will find it useful to make revision diagrams, those with an aural preference will like to read aloud etc (Activity 2).

Sourcing appropriate training and education

Your Primary Care Network General Practice Nurse Lead, or the Education Facilitator at your local learning hub will have information about suitable and appropriate training and education available and may be able to signpost you to funded opportunities.

E-Learning For Health has a range of courses that are available free to NHS workers (including primary care staff): https://www.e-lfh.org.uk

SUMMARY

In the course of our professional, day to day transactions, there are missed opportunities to engage more fully with our patients in order to ascertain their assumptions, beliefs, values and concerns. Gaining greater insights from our patients will help us to understand our professional shortfalls and identify education opportunities to address these.

REFERENCES

1. Berwick D. A promise to learn – a commitment to act. Improving the Safety of Patients in England. London: National Patient Advisory group. 2013

2. Kolb DA. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ Prentice-Hall. 1984

3. Castelli PA. Reflective leadership review: a framework for improving organisational performance. Journal of Management Development 2016; 35 (2): 217-236 Doi: 10.1108/JMD-08-2015-0112

4. Ghaye T, Lillyman S. Reflection: Principles and practice for healthcare professionals. Wiltshire, UK: Quay Books. 2000

5. Goleman D. Working with emotional intelligence. New York. Bantam Books. 1988

6. Greenleaf R, Frick D, Spears L. On Becoming A Servant-Leader. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.1996

7. George J. Emotions and leadership: the role of emotional intelligence. Human Relations 2000; 53: 1027-55 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0018726700538001

8. Thatchenkery T, Metzker C. Appreciative intelligence; seeing the mighty oak as an acorn. Oakland CA, Berrett-Koehler Publishers. 2006

9. Schein E. Humble Inquiry. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. 2013

10. Covey S. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful lessons in personal change, Free Press. 2004

11. Last R. (2012) Narrative leadership Using patient stories to shape better services. Practice Nurse 2012; 42(13): 33-37

12. Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B. Why study narrative? BMJ 1999; 318: 48-50

13. Charon R. Narrative Medicine: A Model for Empathy, Reflection, Profession, and Trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/194300

14. Fleming ND, Mills C. Not Another Inventory, Rather a Catalyst for Reflection. To Improve the Academy 1992; 11: 137-155.