Integrating ‘best evidence’ into general practice nursing

Andrew Finney

Andrew Finney

RN, Dip, BSc, PhD.

Senior Lecturer of Nursing at Keele University, School of Nursing and Midwifery

Charlotte Harper

RN, Dip, BA

Teaching Fellow at Keele University, School of Nursing and Midwifery

Rachel Viggars

RN, DIP, BSc, MSc

Associate Director of Nursing for North Staffordshire GP Federation; Advanced nurse practitioner

Jackie Edwards

RGN, Dip HE, BSc

Nursing Care. Practice Nurse Facilitator for the GP First Training Hub North Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent CCG; Advanced nurse practitioner

Practice Nurse 2020;50(9):26-29

Five years after it first started, a general practice nurse Critically Appraised Topics (CATs) group looks at the CAT approach and the impact of embedding evidence-based practice into day-to-day practice

Applying research findings to clinical decisions is a difficult process for nurses in general practice. It is widely accepted that evidence-based practice is an important pre-requisite for all health professionals to deliver quality patient care. However, there is a discrepancy between the research evidence available and what is delivered in clinical practice.1 This is commonly known as the evidence-to-practice gap or the second translational gap.2

There are reasons for this gap, such as evidence being contested or not aligning with local policy, and no process in place to adopt new evidence. What is clear is that research evidence needs to be actively mobilised to ensure its use by clinicians, commissioners and planners of public health services.3

In North Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent we addressed the evidence-to-practice gap for general practice nurses (GPNs) by forming a group of GPNs, advanced nurse practitioners and clinical academics who would meet as a community of practice,4 to identify areas of clinical uncertainty or clinical variation. We then question these areas through the use of critically appraised topics (CATs).5 Our group launched in 2015 to develop the critical appraisal skills of our GPN workforce.5 In this article we re-visit the CAT methodology and discuss CCG incentives to support such a group, present a CAT example, and discuss the impact of the group on clinical practice and our GPN workforce.

THE APPROACH

Narrowing the gap between academic research and ‘real-life’ general practice is of huge importance and implementation of EBP in primary care seems to be essential for the NHS Long Term Plan.6 The key components for uptake of evidence in clinical practice are the practical component and knowledge.7 We bring these elements together through our partnership between practitioners and clinical academics, in collaboration with Keele University.

We address questions around best evidence through the use of CATs. A CAT is a clinical question derived from a specific patient situation or problem and therefore has direct relevance to nurses who may have previously felt that the concepts of EBP were far removed from day-to-day clinical practice.5 A CAT aims to present research in a way that is accessible and allows nurses to read and adopt the findings in order to influence their practice and, where necessary, implement a change in practice.

A completed CAT provides a summary of the best available evidence to answer a clinical question.8 However, simply having access to the best available evidence does not constitute EBP. It is the appropriate use of this best evidence for the patient group or problem that marks the transition of evidence from simply information to best practice.9

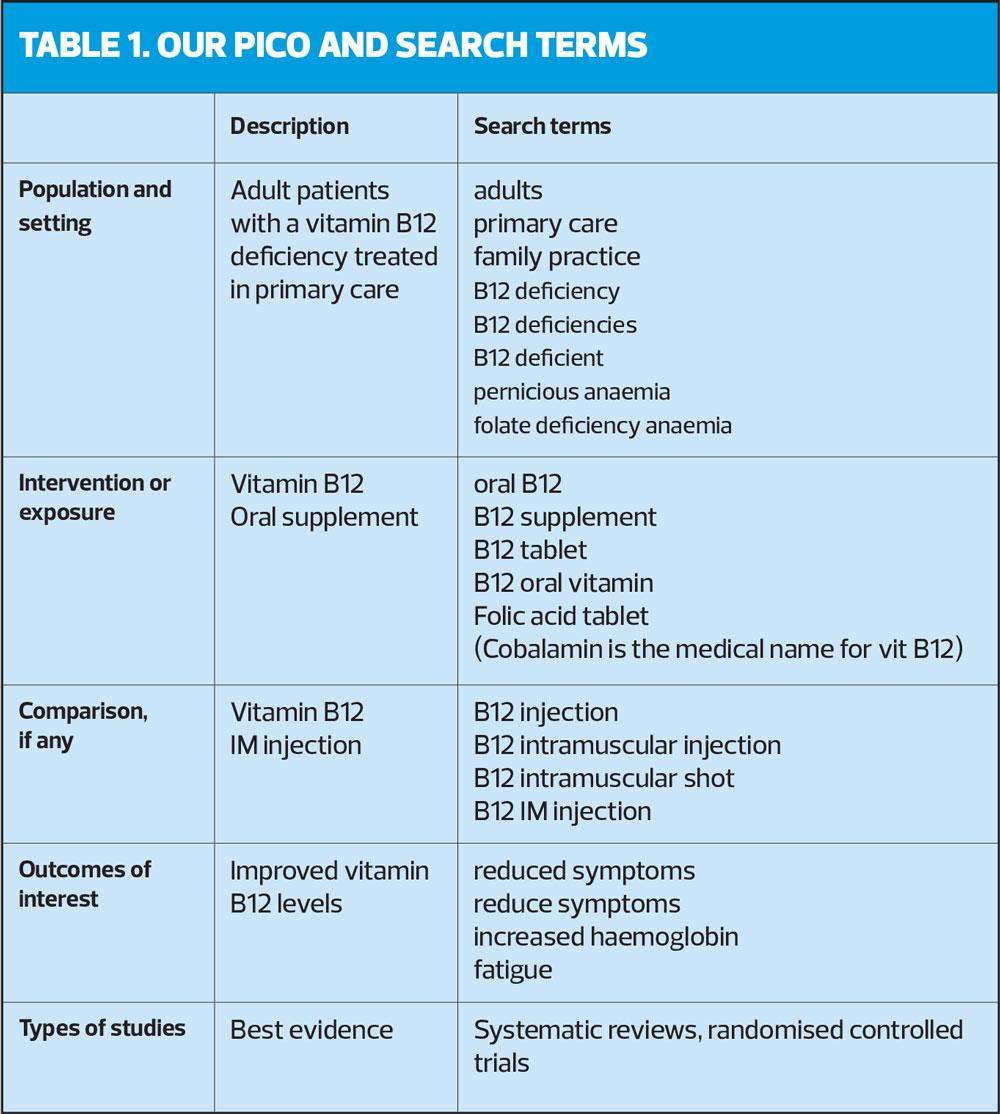

The group undertakes several stages when formulating a CAT. Once an issue is identified, an answerable clinical question is formulated that frames the problem, using a PICO framework (Population or Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) to identify search terms.10

A search strategy is formulated from the question before searches are undertaken by the clinical academics and or a member of the university’s Health Library who will identify and collect the best available evidence. The evidence is then appraised by the group for validity and clinical usefulness using recognised appraisal tools (www.casp-uk.net ; www.cebm.net/critical-appraisal/) in order to produce a clinical ‘bottom line’ and generate the finalised CAT.

Each CAT is usually worked on by a subgroup and then fed back during the main group meetings. Group meetings take place every three months, currently remotely. Depending on the findings, consideration is then given to how the new evidence could be adopted to influence clinical decision-making. Finally, if changes in practice are needed, they are evaluated and reported to the CCG’s research and development (R&D) group.

Despite there being several stages, this is not a lengthy process. CATs can be generated and answered in a relatively short space of time, often dependent on the amount and quality of the evidence available and the skills of the CAT group.5 In many cases, best evidence has been identified in a pre-appraised format through systematic reviews from the Cochrane Group or the Joanna Briggs Institute. Combining the clinical experience of GPNs with that of clinical academics provides a cross-fertilisation of skills and knowledge, and allows clinical academics to keep up to date with current practice issues while nurses are supported to improve their literature searching and critical appraisal skills.

CCG SUPPORT

Our group has been funded by our local CCGs for five consecutive years as part of its robust local approach to implementing the NHS England GPN 10-point plan – the nursing element of the original GP Forward View.11

The CCG recognised the ability of a nursing group to address and contribute to reducing the three gaps identified in the Five Year Forward View: the health and well-being gap, the care and quality gap, and the funding and efficiency gap.12

The CCG recognised that, by supporting the GPNs in continued professional development, local variation in standards of practice could be reduced and – potentially – retention of the local workforce improved. The group supports five aspects of the GPN 10-point:

- Celebrate and raise the profile of general practice nursing and promote practice as a first destination career

- Extend leadership and educator roles

- Increase access to clinical academic careers

- Support access to educational programmes

- Improve working in advanced practice roles in general practice

CAT IN PRACTICE

In 2019, the group started to look at the clinical topic of vitamin B12 deficiency. It had been noted that there was a high volume of vitamin B12 injection administrations, and that this was a time-consuming demand on GPN appointments. At the same time, the group was aware that there seemed to be very few patients on oral vitamin B12 (cobalamin) supplements and this provided the impetus for our CAT.

Group members were able to undertake a small audit of patients on either oral or intramuscular (IM) vitamin B12 from their individual practices. It became evident that vitamin B12 injections created a significant, but possibly unnecessary workload for the practices.

Our CAT Question

’In patients that are vitamin B12 deficient, is oral vitamin B12 supplementation as effective as intramuscular B12 injection?’

Evidence

A Cochrane systematic review13 was identified as best evidence and reviewed by the group.

Clinical Bottom Line

Administration of vitamin B12 via IM injection is common, however the results from the literature suggested that oral vitamin B12 may be as effective as IM for some patients. Use of oral B12 may reduce practice nurse time and is less invasive than IM treatment.

Implications for practice

Group members take CAT findings back to their practices for discussion with the GP partners. The final view of the group was that all newly diagnosed patients with vitamin B12 deficiency (cobalamin <200pg/ml) should have their intrinsic factor checked. If this is negative then oral supplementation is appropriate, with a repeat B12 blood test after 3 months. If this is then >200pg/ml then patients can continue with oral treatment. If the intrinsic factor is positive, then the BNF guidelines for initiating lifelong injectable vitamin B12 therapy should be considered. Patients with pernicious anaemia, Crohn’s disease or a gastric bypass should remain on injectable B12.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE – CASE STUDY

Gladys, female, 84 years

Past Medical History: IHD, Parkinson’s disease, Diverticular disease and Alzheimer’s disease.

Gladys was seen in the haematology clinic in May 2017 after being referred by her GP. Gladys had presented with a sore tongue, and initial blood tests suggested possible anaemia. Gladys was then checked for vitamin B12 deficiency. Her serum vitamin B12 (cobalamin) result returned at 176pg/ml (range 200-900). The hospital discharged Gladys with a diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency and a request to commence on vitamin B12 injection therapy.

Gladys has been maintained on IM B12 injections, undertaken by the practice nurse every 12 weeks, requiring her to attend the practice accompanied by her daughter.

Vitamin B12 injections were initiated as per the BNF – 1mg 3 times a week for 2 weeks, administered by the practice team, and then 1mg every 3 months.

Following the evidence from the CAT question, it was recommended that Gladys had her intrinsic factor checked, supported by a letter from her GP advising her that she may be able to have oral vitamin B12 supplements rather than the injections. The intrinsic factor was negative. This provided the recommendation to switch to oral cobalamin.

After discussion with Gladys and her daughter, Gladys happily switched to oral supplements, with a repeat blood test arranged for 3 months after the change. The follow-up blood tests demonstrated that serum vitamin B12 levels were 955pg/ml. Gladys no longer required IM vitamin B12, obviating the need for 3 monthly visits to the practice.

- During the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic we were able to use the Gladys example as a way of auditing and moving many patients over from IM to oral vitamin B12 to prevent footfall within the practice. This was done safely with the support of the CCG Medicines Optimisation team.

IMPACT

The impact of our EBP CAT groups has been demonstrated in both the clinical and academic environments. Academically, GPNs have been brought into the research cycle with many GPNs and their practices now supporting local clinical trials. GPNs have developed their research awareness through ‘bitesize’ teaching sessions aligned to the methods used within the sourced evidence.

The findings of CAT questions are fed back to the CCG R&D group to consider any changes in practice that might be needed. GPNs take the findings from group meetings back to their practices and share them with colleagues at practice team meetings. The findings are also shared by the CCG as part of their newsletter, and completed CATs are published on a dedicated web page, at https://www.keele.ac.uk/pcsc/research/impactacceleratorunit/evidenceintopracticegroups/practicenursing/

In the five years since the group began, we have developed not only the research skills but also the leadership skills of the group. Several of the group have achieved Masters degrees in Advanced Clinical Practice, and some have become Advanced Nurse Practitioners. One group member has moved into an educational role. Group members have gained the confidence to present at specialist conferences and to teach on educational programmes such a ‘Fundamentals in General Practice Nursing’.14 Seven members of the group have also been recognised and awarded the title ‘Queen’s Nurse’ from the Queen’s Nursing Institute.

The key ingredients for success of the group include:

- Support given by academic institutions and health libraries

- Clinical and academic leadership of the groups

- Consistent collaborative effort within the groups that allows for co-design of questions and clinical bottom lines

- Funding from CCGs

- Engaged GPNs and clinical academics.

One other recognised ingredient is the merger of evidence-based practice with practice-based evidence. The academics are keen to quickly apply the best evidence to practice, but the GPNs are more cautious, preferring first to audit and check on their own practice populations. This amalgamation of the two approaches allows for a more targeted approach to implementing change from CAT findings.

This model has the potential to be rolled out nationally, and the potential to have a significant impact both on the delivery of evidence-based care, thereby improving clinical outcomes, reducing costs and reducing clinical variation. It also assists in the identification of the areas of practice for future research. A network of CAT groups sharing the results of each other's work could help to achieve this ambition. There is also the potential for patient representatives to be involved in this process so that the questions asked are relevant and worthwhile for both patient and practitioner.

CONCLUSION

The North Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent CCGs have led the way in developing the evidence-based practice skills of their GPN workforce through a partnership with clinical academics at Keele University. This partnership has brought the GPN role to the attention of primary care researchers and those same researchers have helped the workforce to become leaders of change in their own practice settings, taking research evidence from the page and applying it to the clinical setting, for the benefits of the patients in their care.

REFERENCES

1. Wenke RJ, et al. The effectiveness and feasibility of TREAT (Tailoring Research Evidence and Theory) journal clubs in allied health: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Medical Education 2018;18 (1):104

2. Lau R, et al. Achieving change in primary care-causes of the evidence to practice gap: systematic review of reviews. Implementation Science 2016;11:1

3. Van der Graaf P, et al. Localising and tailoring research evidence helps public health decision making. Health Information & Libraries Journal 2018;35:202–212

4. Wenger E, et al. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge. 2002; Harvard Business Press: 1st edition

5. Finney AG, et al. Critically Appraised Topics (CATs): A method of integrating best evidence into general practice nursing. Practice Nurse 2016;47(3):32-34

6. NHS England (2019) The NHS Long Term Plan. NHS England, London

7. Lizardo LM, et al. Exploring the perspectives of allied health practitioners toward the use of journal clubs as a medium for promoting evidence-based practice: a qualitative study. BMC Medical Education 2011;11:66

8. Foster N, et al. Critically Appraised Topics (CATs): one method of facilitating evidence-based practice in physiotherapy. Physiotherapy 2001;87(4):179-190

9. Gordon J, Watts C. Applying skills and knowledge: Principle F. Nursing Standard 2011;25 (33) 35-37

10. Richardson WS, et al. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence based decision making. ACP Journal Club 1995;123 (3) A12-13.

11. NHS England (2016) General Practice Forward View. NHS England, London

12. NHS England (2014) Five Year Forward View. NHS England, London

13. Wang H, et al. Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018;3:CD 004655

14. Finney AG, et al. Taking an academic approach to training for new GPNs. Practice Nurse, June 2016;46(6):30-33