Reducing health inequalities for people with learning disabilities

Hazel Ashmore

Hazel Ashmore

RNLD

Senior Clinical Manager

Home from Home Care

Practice Nurse 2020;50(9):11-14

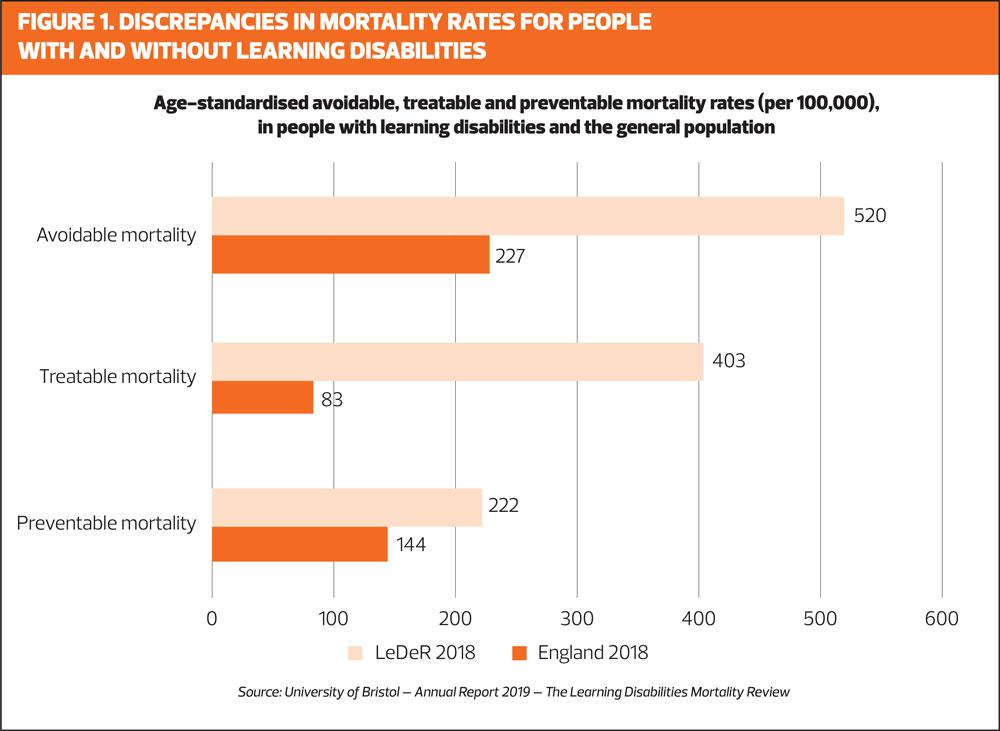

People with learning disabilities are twice as likely to die from an avoidable medical cause as the general population but annual health checks can play a valuable role in identifying potential issues and instigating early and effective treatment

The Learning Disabilities Mortality Review (LeDeR) programme was set up to evaluate premature mortality and health inequalities among people with learning disabilities, in order to improve the standard and quality of care they receive. The fourth LeDeR report, considering deaths in 2019, concluded that overall avoidable deaths (those where conditions were treatable or preventable) accounted for 44% of deaths in people with learning disabilities. The same figure for the general population was 22% (Figure 1).1

In 2018, 85% of people who died were 65 and over. In contrast, only 37% of people with a learning disability who died in 2018 were aged over 65.1 The prevalence of long term conditions (LTC) in this population is also high: 94% of those reviewed in the LeDeR report had at least one LTC, and on average they had three.1

The LeDeR report also confirmed that people with learning disabilities have poorer health outcomes when compared with the general population and that, to an extent, these poor outcomes were avoidable.1 The fact that constipation remains one of the leading conditions contributing to premature death in the 21st century is shocking.1

The most frequent cause of death were diseases of the respiratory system (20%), diseases of the circulatory system (15%), and congenital and chromosome abnormalities (14%). The most commonly reported conditions were pneumonia and aspiration pneumonia.2

People with long term conditions now account for 50% of all GP appointments, 64% of all outpatient appointments and over 70% of all inpatient bed stays.3 People with learning disabilities have a greater risk of death from respiratory issues and have been eligible for a flu vaccination since 2014, but uptake has remained low at less than 50%.4,5 Flu vaccination uptake figures for Winter 2019-2020 show that this is much lower than in patients over 65 (72.4%).3 With the apparent increased risk for respiratory illness in people with a learning disability, and current concerns about the second wave of COVID-19, this is a matter of great concern.

Guidance has been issued to confirm that GP practices should continue to offer annual health checks to people with learning disabilities during the pandemic.6

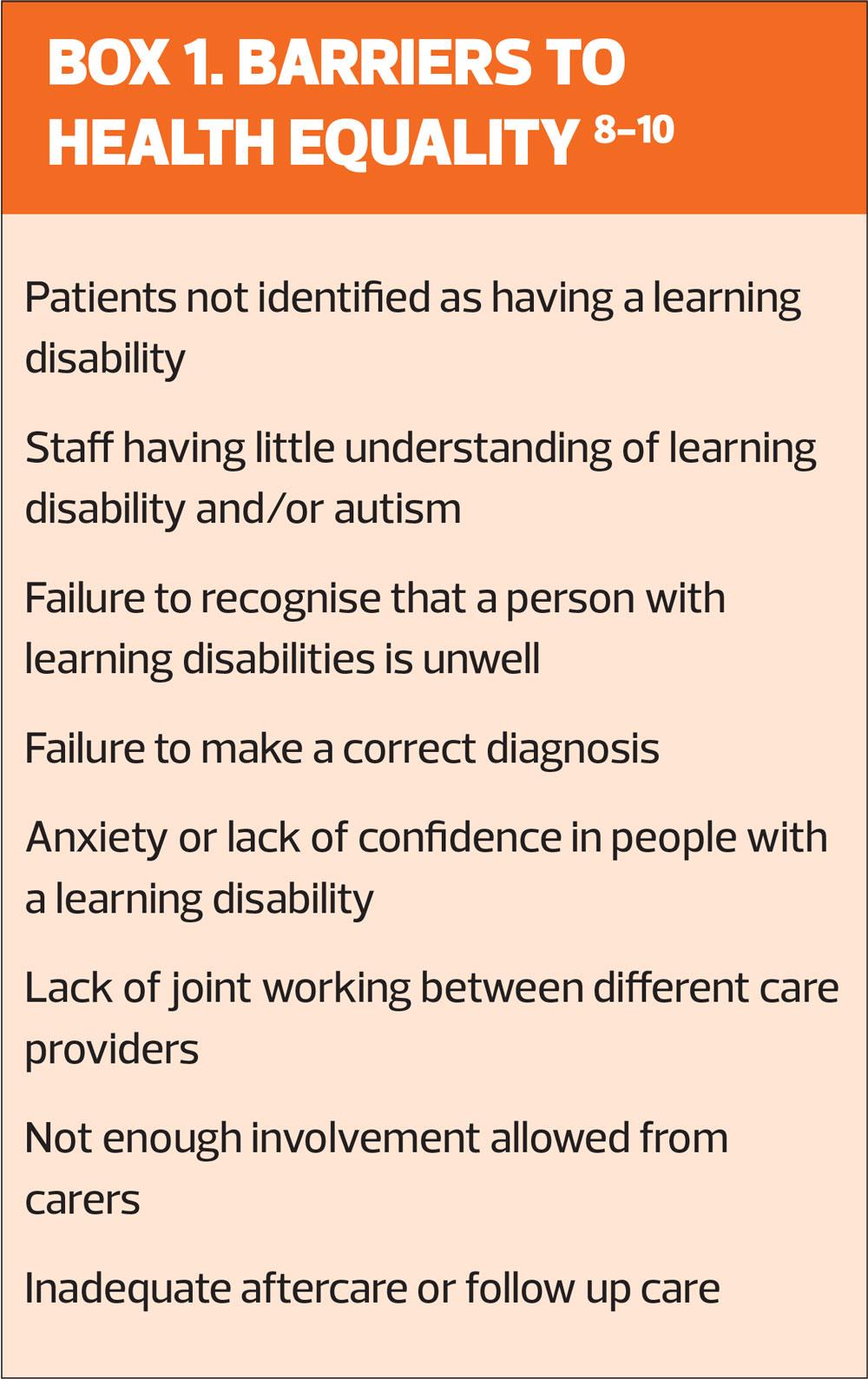

BARRIERS TO HEALTH EQUALITY

A number of common barriers to health equality have been identified, and are summarised in Box 1.

The Learning Disability Observatory is working on a new project (the Health and Care project) to gain a more detailed understanding of the health of people with a learning disability in each part of the country. This will evaluate the care they get and how this compares with the care of people without a learning disability. The areas to be covered include general health measures, health checks and immunisation.7 This information will help clinical commissioning groups and other health and social care planners to ensure that people with learning disabilities receive the same standard of care as other people.

More than a decade ago, in 2006, the Disability Rights Commission argued that everyone ‘with a role in the provision of primary care health services to people with learning disabilities and/or mental health problems must act now to tackle the inequalities in physical health and primary healthcare services they experience’.10

The NHS Long-term plan last year set out the need for improving partnership working between primary care and care homes.11 In understanding some of the barriers to good healthcare and how these barriers can be overcome, this partnership is essential. GPs and practice nurses have the expertise to investigate, diagnose and prescribe care and treatment. The circle of support around an individual with learning disabilities – including family members and/or highly skilled support workers – should be used to identify how a patient can best be supported when accessing primary health care services. This includes sharing information on their general wellbeing (based on both objective data and observations).

OVERCOMING BARRIERS

The annual health check has the potential to be a powerful tool as part of this partnership working and in making a significant impact on improving health outcomes and reducing inequalities.

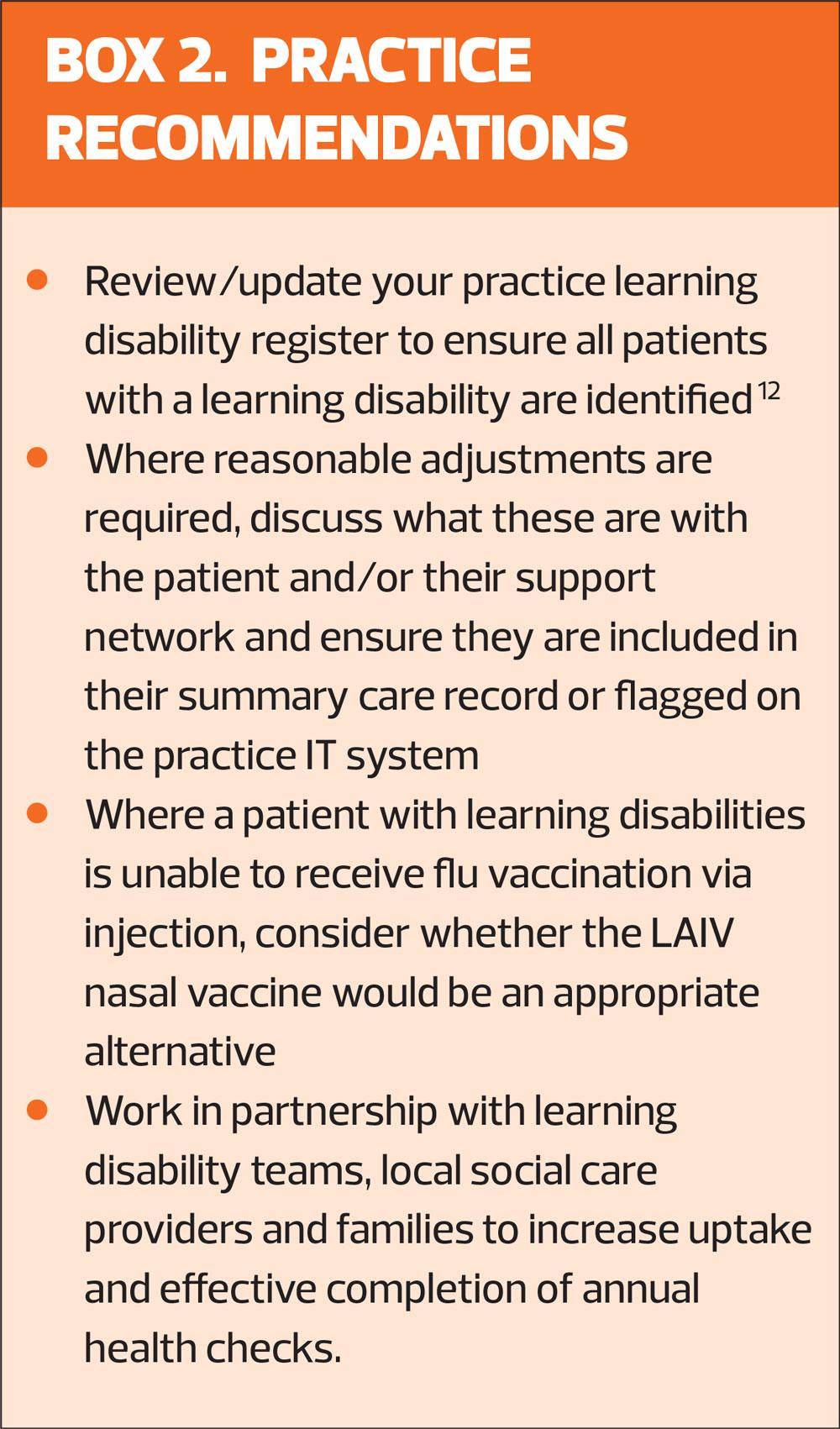

Annual health checks are available to all people over 14 with learning disabilities and can help to identify new health conditions early. They also prompt a review of existing conditions or risks associated to specific diagnoses, so these can be monitored proactively. Uptake of the annual health check has slowly improved since implementation in 2014 but remains suboptimal at 56%.12

It is also important to understand that this is not 56% of the total population with learning disability, but 56% of those on the learning disability register. The recording of learning disability in primary care is poor. A range of codes is used to identify learning disability and the proportion of people who are known to healthcare services is estimated to be around 25%.12 The reality is that only a small minority of people with learning disabilities are being offered, or are receiving, annual health checks. Improving the implementation of the learning disability register might help to address this issue, and NHS England has produced guidance on how to improve inclusion of all people with a learning disability, which includes a list of the relevant READ codes for easy reference.12

For a health need to be met, it needs to be identified.8-10 This is one key area where barriers for people with learning disabilities can be overcome. It may be hard for the person with learning disabilities to express what is wrong, and those in their immediate support network may not recognise that they are unwell, which means an accurate diagnosis may not be made.9,10 Often though, those who know the individual will notice changes in their mood, behaviour, engagement, support needs, seizure presentation, appetite, skills etc. that indicate that something is different. The challenge then is to communicate this to clinicians who can then investigate the cause. The author’s organisation, Home from Home Care, has developed an IT platform, where all data about the individuals we support is recorded, as objectively and simply as possible. This allows us to produce reports that show health and wellbeing holistically, allowing identification of correlations or patterns that can then be interpreted by healthcare professionals.

Access

A further barrier is accessing services. This may be difficult for people with learning disabilities who can sometimes struggle with anxieties around unfamiliar places, people or activities. Reasonable adjustments, as required under the Equality Act can be made,13 but often information specific to each individual may not be shared with the people who need to know it. Adding this information to a summary care record or flagging it on the practice computer system, can have significant impact on the experience a person has with health care services and, ultimately, on their health outcomes. As part of work to support the Transforming Care programme, a way of having a digital ‘reasonable adjustment flag’ is being developed so that vital information is alerted to, and accessible by, all healthcare professionals.14,15

Practice nurses and GPs have a limited time with their patients (even with reasonable adjustments to extend appointment times). They are therefore reliant on support workers and family members to understand unique complex behaviour and communication systems. Learning disability nurses in social care and in the community, working in partnership with local GP practices, are ideally placed to assist people with learning disabilities and their support workers/family to communicate their needs and concerns to clinicians effectively.

THE ANNUAL HEALTH CHECK

There are two parts to the annual check, the preliminary part, which can be completed by a practice nurse or other suitably qualified practitioner, and the second part to be completed by the individual’s GP.16

The preliminary section collates basic information on diagnoses, specific symptoms (which often have associated health risks), reasonable adjustments, involvement of other specialist practitioners (e.g. speech and language therapists, occupational therapists), lifestyle, life skills, screening and baseline assessments. The section completed by the GP includes a physical examination, review of medication and a review of respiratory, gastrointestinal and other systems. The check considers primary cancer screening and immunisation status – in which uptake among people with learning disabilities is low.17 For flu immunisation, it is worth noting that the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) nasal spray can be used off license for people with learning disabilities, who may be needle-phobic.5

The Royal College of General Practitioners18 has produced a toolkit which offers step by step guidance on preparation and completion of the checks.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

In summary, people with learning disabilities have poorer health outcomes and are more likely to die prematurely than people without a learning disability. They face many barriers to receiving good health care but practice nurses working in partnership with families, social care providers and learning disability colleagues can help to overcome these barriers and significantly improve these patients’ health outcomes and quality of life, and reduce the inequalities experienced by people with learning disabilities every day.

REFERENCES

1. Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP). Learning Disability Mortality Review (LeDeR) programme Annual report); 2020 https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/the-learning-disabilities-mortality-review-programme-annual-report-2019/

2. Heslop P, Blair P, Fleming P, et al. Confidential Inquiry into premature deaths of people with intellectual disabilities in the UK: a population-based study . Lancet 2013;383(9920):889-895

3. Public Health England. Seasonal Influenza vaccine uptake in GP patients: winter season 2019 to 2020; June 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/894970/Annual-Report_SeasonalFlu-Vaccine_GPs_2019-20_FINAL.PDF

4. National Learning Disabilities Professional Senate. Delivering effective specialist community learning disabilities health team support to people with learning disabilities and their families or carers. January 2019

5. Public Health England. Guidance. Flu vaccinations: supporting people with learning disabilities; updated 25 September 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/flu-vaccinations-for-people-with-learning-disabilities/flu-vaccinations-supporting-people-with-learning-disabilities

6. National Development Team for Inclusion: A guide to health checks and coronavirus https://www.ndti.org.uk/uploads/files/Annual_health_checks_and_Coronavirus.pdf

7. Department of Health. Long term conditions compendium of Information: 3rd edition; 2012 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216528/dh_134486.pdf

8. Allerton L, Emerson E. British Adults with chronic health conditions or impairments face significant barriers to accessing health services Public Health 2012; 126(11): 920-927

9. MENCAP. Health Inequalities. https://www.mencap.org.uk/learning-disability-explained/research-and-statistics/health/health-inequalities

10. Merrick J, Merrick E. Equal treatment: Closing the Gap. A Formal investigation into physical health inequalities experienced by people with learning disabilities and/or mental health problems. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil 2007;4(1):73 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2006.00100.x

11. The NHS Long-term plan; June 2019. www.longtermplan.nhs.uk

12. NHS England & Improvement. Improving Identification of people with a learning disability: guidance for general practice. Updated October 2019 https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/improving-identification-of-people-with-a-learning-disability-guidance-for-general-practice.pdf

13. Legislation.gov.uk 2010 Equality Act 2010 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/pdfs/ukpga_20100015_en.pdf

14. NHS England. Transforming Care. Programme Model Service Specifications: Supporting implementation of the model 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/model-service-spec-2017.pdf

15. Robinson S. Closing the Healthcare gap for people with learning disabilities; June 2020 https://digital.nhs.uk/blog/transformation-blog/2020/closing-the-healthcare-gap-for-people-with-learning-disabilities

16. NHS England. National Electronic Health Check (Learning Disabilities) Clinical Template: A summary and overview of the Learning Disability Annual Health Check; 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/south/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2017/03/Final-LD-Template-Summary-1403-V10.pdf

17. NHS Digital. Health and care of people with Learning Disabilities, Experimental Statistics: 2018 – 2019 [PAS]; Jan 2020. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-and-care-of-people-with-learning-disabilities/experimental-statistics-2018-to-2019/cancer-screening

18. Hoghton M, Lamb K, Van Dam M. Royal College of General Practitioners Health Checks for people with learning disabilities toolkit. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/resources/toolkits/health-check-toolkit.aspx

Related articles

View all Articles