Admiral Nursing case management in primary care

Beth Goss-Hill

Beth Goss-Hill

Consultant Admiral Nurse, Dementia UK

Zena Aldridge

Admiral Nurse Research Fellow,

PhD student, De Montfort University, Leicester

Practice Nurse 2020;50(10):12-17

As we all know, general practice is under increasing pressure – not least because of the imminent COVID-19 vaccination campaign – so it is good to know that Admiral Nurses are on hand to provide support for people living with dementia, their families and carers. This is how they can help to manage and reduce dementia-related crises

There are 850,000 people living with dementia (PwD) in the UK.1 Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe a group of symptoms that are characterised by memory loss, behavioural changes, loss of cognitive and social functioning which are caused by progressive neurological disorders.2 Two thirds of PwD live in the community with the remaining third living in residential and nursing care.1 PwD are known to have on average at least three comorbid conditions,3 which may include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, vascular or cardiac diseases and muscular skeletal disorders.4

Providing peri- and post-diagnostic support for families affected by dementia is difficult in primary care due to inconsistencies in funding and service capacity. There is a postcode lottery when it comes to the provision of specialist dementia support to manage complex health and social care needs resulting from dementia.5,6 Despite this, the first port of call for PwD and their carers when they need information and support to manage challenges resulting from dementia and other associated comorbid conditions is the GP practice.7,8 However, some carers are reluctant to contact their GP due to stigma or feeling ashamed.9 Equally, they may be deterred by difficulty in accessing appointments, and find appointment times insufficient to meet their complex needs. Conversely, GPs report their frustration at not having adequate time to support the PwD and their carers, and cumulatively these factors exacerbate suboptimal experiences in primary care settings.8,10

There is a growing need to increase the provision of dementia specialism in primary care rather than trying to change the practice of primary care clinicians.11 This requires the inclusion of skilled and knowledgeable practitioners who are able to address complex needs arising from dementia. Admiral Nurses are well equipped to fill this gap, and can provide specialist biopsychosocial, relationship-centred care to families affected by dementia as well as supporting health and social care colleagues in the primary care setting.12

ADMIRAL NURSING

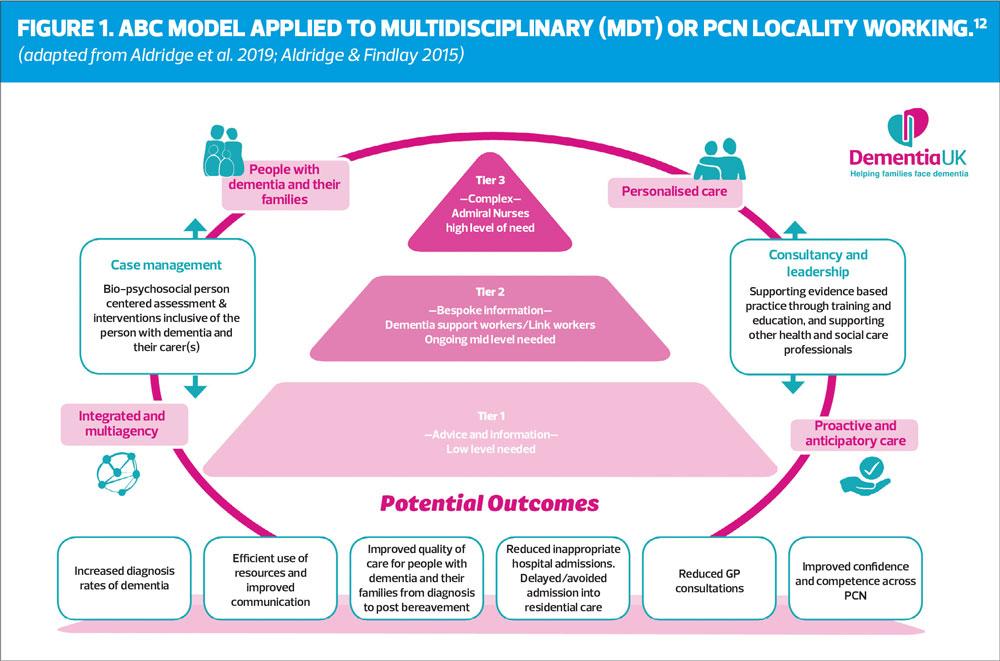

Admiral Nurses are dementia specialist nurses who work with complex cases within the ABC tiered model of dementia support (Figure 1).5 The inclusion of Admiral Nurses in Primary Care Networks (PCN) has the potential to improve the support offered not only to families affected by dementia but also to healthcare professionals in the wider primary and community care team.12

Working alongside generalist colleagues, Admiral Nurses offer specialist support to both the PwD and their family carers with referrals coming directly from their colleagues within the multidisciplinary team (MDT)/PCN with many potential outcomes outlined within the model (Figure 1).12

Through development of triadic relationships with both the PwD and their family carer, Admiral Nurses offer interventions that support the family in totality as opposed to individually.13 This is achieved by offering specialist biopsychosocial assessments and interventions that enable a proactive and anticipatory approach as opposed to one that is reactive and requires a state of crisis within a family before they get a service response.

Admiral Nurses also offer informal training and education to generalist colleagues on many aspects of dementia care, alongside acting as a point of contact to consult, supervise and mentor colleagues within the MDT/PCN to improve confidence and competence. This addresses a gap, reflected in the evidence base that highlights the need to ensure a skilled workforce and improve staff confidence staff confidence in relation to the care of people with dementia across services and throughout the dementia trajectory.12,14

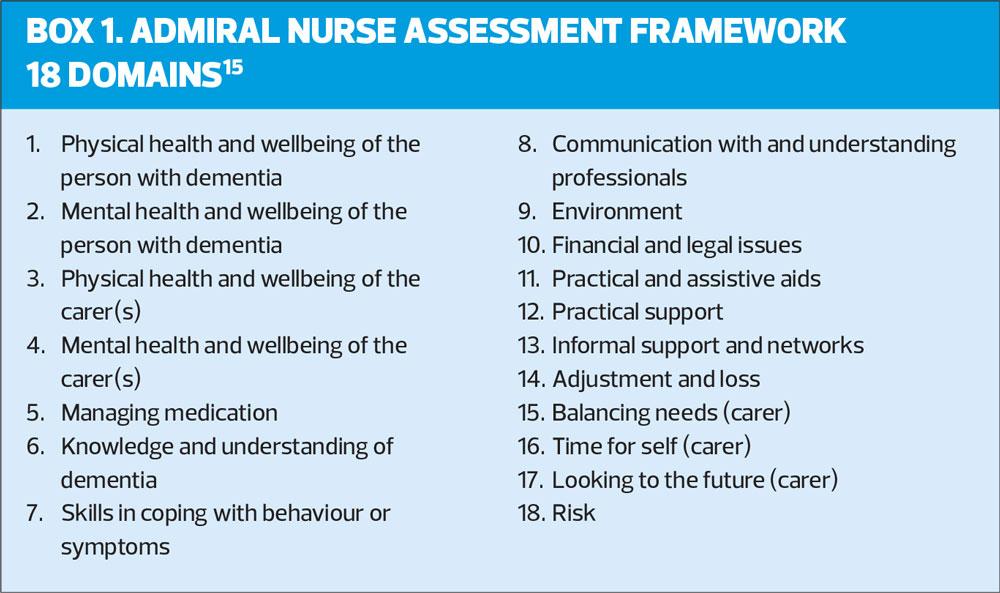

Admiral Nurse assessment

The Admiral Nurse Assessment Framework (ANAF) (Box 1) is an 18-domain, holistic assessment to assess the needs of the PwD and their family carer(s). This comprehensive assessment prompts consideration of their physical, mental and social wellbeing to inform care planning and care interventions that are relationship focused.15 Implementing enhanced communication skills, and a biopsychosocial approach an Admiral Nurse allows the PwD and their family carer to articulate and express their needs.

The role of an Admiral Nurse in primary care

Being an Admiral Nurse in primary care requires a high level of confidence and competence as the role demands considerable autonomy, expertise, flexibility and compassion to address the complex multi-faceted needs of people with PwD and their carers. Despite being a challenging role, the ability to provide specialist dementia care to families who are feeling alone and vulnerable is a privilege and extremely rewarding.

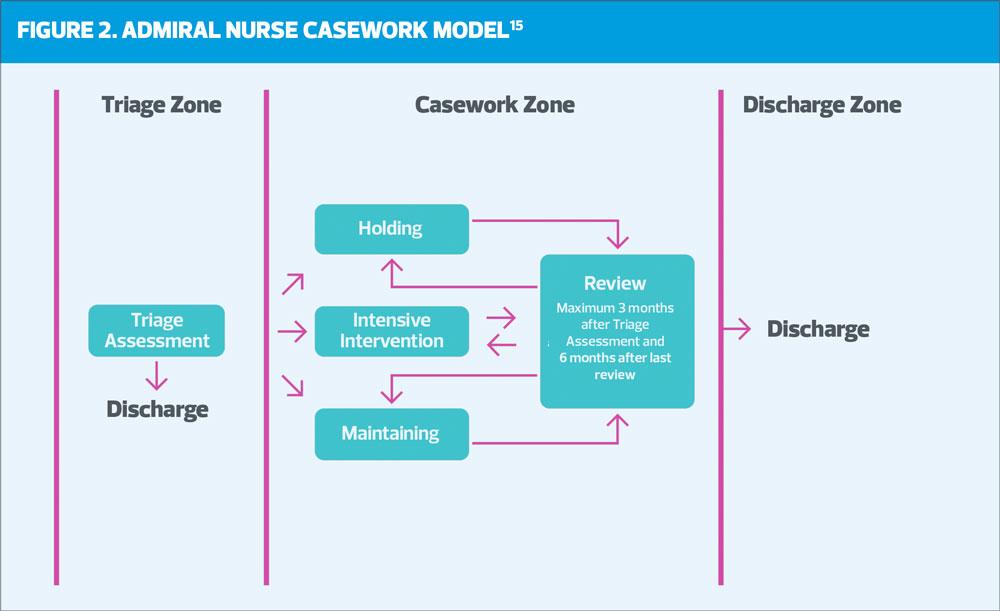

Starting each day at the GP practice, new referrals from MDT/PCN colleagues are triaged by the Admiral Nurse to determine the level of urgency and need using the Admiral Nurse case management model (Figure 2).16 This model ensures that the most complex cases, i.e. those in need of intensive support, are prioritised.5,12 A review of their medical notes advises of assessments and interventions already undertaken and what the current concerns might be alongside any known risks. Comorbidities which may be impacting upon either the carer or the PwD’s health and/or social care needs, such as diabetes or heart failure, are also identified so they are can be considered holistically rather than in isolation.

Initial appointments are offered with a choice of location. Being seen at home is often welcomed by carers and improves accessibility and engagement because it reduces the potential challenges of getting the PwD, or themselves, to the GP practice. Appointments may include other family members which can improve wider family relationships, improving understanding of dementia and its effects, while offering a broader view of the difficulties experienced by the family.

SOME COMMON CONCERNS

Due to the complex nature of dementia and how it affects people differently, the reasons for accessing the Admiral Nurse Service are varied. However, the lack of a diagnosis or failure to seek a diagnosis is a recurring issue, which prevents a PwD and/or their carer from accessing appropriate and timely specialist support and treatments from their local Memory Assessment Services (MAS).

This can negatively impact upon the family’s opportunity for adjustment to the diagnosis,9 but equally can prevent identification and treatment of reversible conditions that may be the cause of presenting symptoms. The provision of specialist peri- and post-diagnosis support can overcome potential barriers if dementia is suspected or known, by ensuring that PwD and their families understand the importance and potential benefits of a thorough assessment. Reluctance to seek a diagnosis can strain relationships between the PwD and their family but offering early psychosocial support can reduce any negative effects.17 The PwD may be fearful of losing their autonomy and independence.18 This can often lead to increased anxiety and result in the PwD avoiding all contact with professionals.

Consequently, this leads to poor understanding and management of their dementia and its impact on any other comorbid condition(s) which, without the correct management, can negatively interact with each other causing further complications or an exacerbation of one or more of the individual diseases.19 Ultimately, this can result in reduced quality of life and increased risk of health and social care needs resulting from crises. Admiral Nurse support can improve engagement and timely referral to MAS, ameliorating some of the negative effects of a delayed diagnosis and access to appropriate management.

THE NEEDS OF FAMILY CARERS

There are an estimated 670,000 informal carers of PwD with over 60% , who receive little or no support in their caring role.1 Being a family carer for a PwD carries increased risk of psychological stress and physical ill-health, with around only half of all carers reporting that they look after themselves and pay attention to their own needs.1,19,20

Many family carers focus on the needs of the PwD and do not see their GP to address their own health concerns. Some carers fail to attend essential health checks or delay necessary treatments, negatively impacting upon their own health and wellbeing.21 This is a significant cause for concern, as the failing health of the family carer is also likely to have a major impact on the wellbeing of the PwD, and can contribute to a breakdown in care and possible premature admission to residential care for the PwD.22,23 Family carers report that on more than one occasion they could not attend the practice as a result of their caring responsibilities, they were unable to leave the PwD at home alone yet found bringing the PwD with them to an appointment too stressful.

Consequently, carers may present in crisis, often as a result of feeling unable to cope any longer, or continue in their caring role. This may be because of their own ill health or increasing episodes of ‘distress behaviours’ expressed by the PwD resulting in the family carer becoming exhausted, or worse, burned out.24 Admiral Nurses can help carers to identify and understand their own needs and the potential triggers of distress behaviours, offering them strategies to reduce and manage them, which improves relationships and outcomes for both the carer and the PwD.25

Admiral Nurses can also offer emotional and psychological support enabling carers to explore their complex feelings and emotions, such as, guilt, anticipatory grief/loss, anxiety and exhaustion. An exploration of these feelings may provide opportunities to identify resources and engage other key professionals to ameliorate some of the negative impact of their caring role. This case management approach can help carers improve their own health and wellbeing, and their relationship with the PwD enabling them to continue as carer, or alternatively support them through care transitions.

CASE STUDY*

*Some details have been changed to protect patient anonymity.

John lives with his wife, Alice, to whom he has been married to for 53 years.* They have no local support networks and their children live some distance from the family home. John was diagnosed with COPD 4 years ago, and prostate cancer 6 months previously. John’s GP was contacted by an oncology nurse who was concerned that John had not been regularly attending radiotherapy and follow up appointments. In addition, the nurse was concerned about John’s memory as when she contacted him to ask why he had not attended, he said he had forgotten. The oncology nurse wanted to check if the GP was aware of any other concerns.

The GP arranged an appointment for John, but he did not attend and refused to book a further appointment. As a result of the concern that he may be experiencing some cognitive decline, and knowing that John cared for his frail wife, it was agreed that the Admiral Nurse would try to make contact and see him, to see how he was coping at home.

The Admiral Nurse called John and asked if she could visit him at home, to which he reluctantly agreed. When the Admiral Nurse arrived, John appeared at the door exhausted, stating he had forgotten she was coming. The Admiral Nurse was able to persuade him to let her in, despite his claim that he was alright. His home was unkempt, his wife Alice was shouting for him, and he said that he needed to get her dressed.

The Admiral Nurse offered to help, and although initially reluctant, he agreed. It quickly became apparent that Alice had significant cognitive impairment. While helping, the Admiral Nurse was able to assess some of Alice’s care needs and ask John how he was coping. It was clear that John was struggling physically, mentally and emotionally with Alice’s care. Through careful and sensitive questioning, the Admiral Nurse was able to ascertain that John had been caring for his wife for the past 3 years due to known multiple health conditions. He had noticed that over recent months her cognition had significantly deteriorated, and he was no longer able to safely leave her alone. That was why he had not attended his radiotherapy appointments. John also had worries about his own memory. He had not mentioned his wife’s condition or his concerns about his own memory to anyone as he feared Alice would be ‘taken away’.

The Admiral Nurse took time to explain to John what help, and services might be available to him and reassured him that she would support him to keep Alice at home – but advised him that he would need to look after his own health. He broke down in tears of relief.

The Admiral Nurse arranged an urgent package of care, with carers attending twice a day initially to enable him to restart his radiotherapy.

Subsequently, the Admiral Nurse planned weekly visits where she was able to assess John’s needs further. It became apparent that his memory functioning was variable. The Admiral Nurse carried out dementia screening and blood tests and was able to reassure John that this was likely to be a result of his poorly-managed COPD and prostate cancer in addition to fatigue as a result of caring. These effects improved over time as a result of restarting his cancer treatment, improved management of his COPD, and through the introduction of a care package for Alice. John agreed to a referral to the local MAS for Alice, who was subsequently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and started on cholinesterase inhibitors.

The Admiral Nurse facilitated discussions around planning for their future care needs by supporting them both to develop an Advance Care Plan. John stated that he felt like a weight had been lifted from his shoulders. He had been fearful about what would happen to Alice if he died or if he too developed dementia, and these worries were overwhelming him. Though ongoing case management the Admiral Nurse continued to offer specialist support but also worked collaboratively with other professionals to arrange an increased package of care, to include once-weekly day-care for Alice, home adaptations and assistive technology, and for both Alice and John to attend a local activities group to extend their social network and gain much needed peer support and interaction.

Case Outcomes

The Admiral Nurse had the specialist skills, knowledge and time which enabled consideration of both John and Alice holistically, and she was able to proactively involve other health and social care professionals when John was willing to accept their input. Health and social care services in England are fragmented and tend to focus on the person with dementia or their carer as separate entities, managing one problem at a time, making effective case management in multi-faceted cases like John and Alice’s difficult to achieve. It is clear that without the comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment, implementation of bespoke interventions and ongoing case management of both John and Alice’s multiple needs, John’s health would have declined impacting on his ability to care for Alice leading to crisis. It is highly likely that Alice would have been prematurely admitted to residential care as a result. Alice accessed appropriate treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, which coupled with increased social engagement improved her mood and consequently reduced her distress behaviours and improved her relationship with John. They both benefitted from the increased social support, which in turn improved their psychological and emotional wellbeing.

WIDER IMPACT OF THE ROLE

This example of the Admiral Nurse role is consistent with previous evaluations of primary care-based Admiral Nurse services, which have been observed to improve the physical, emotional and mental wellbeing of people with dementia and their families.12,15,26

As well as the direct impact of the role for PwD and their family carers it has been shown that the presence of an Admiral Nurse providing case management in primary care has the ability to develop the skills and knowledge of generalist colleagues. This improves the identification and subsequent diagnosis of dementia, while promoting integrated working across the wider MDT by implementing a biopsychosocial rather than medical model of dementia care.16,26

Admiral Nurse case management offers potential benefit to patients, their carers, and professionals through continuity of care with a named, trusted individual who can act proactively to prevent a crisis.27 This reduces reliance on GP consultations as PwD and their family carers are able to access the specialist support they need, in a timely way, reducing the risk of premature transition to care homes and avoiding unnecessary hospital admissions, particularly at end of life.26

CONCLUSION

The provision of Admiral Nursing in primary care creates an opportunity to identify and support families who are struggling with the impact of dementia and offer them specialist support to meet their complex needs. Despite the emphasis on timely diagnosis of dementia, the provision of effective specialist post diagnostic support has been patchy. To rectify the postcode lottery of dementia support services that currently exists needs a proactive approach to peri- and post-diagnosis dementia support. Establishing Admiral Nursing in PCNs provides this much needed specialist support for both families living with dementia, and colleagues working in over stretched primary care services.

REFERENCES

1. Prince M, Knapp M, Guerchet M. et al. Dementia UK: Second Edition-overview. Alzheimer’s Society; 2014

2. Fratiglioni L, Qiu C. Epidemiology of dementia. In: Dening T, Thomas A. (Eds) Oxford Textbook of Old Age Psychiatry, 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013; 389-413

3. Timmons S,"¯O’Shea E,"¯O’Neill D,"¯et al. Acute Hospital dementia care: results from a national"¯audit."¯BMC Geriatrics 2016;16:113"¯

4. Bunn F, Burn AM, Goodman C, et al. Comorbidity and dementia: a mixed methods study on improving health care for people with dementia (CoDem): NIHR Journals Library: 2016 Feb (Health Services and Delivery Research).

5. Aldridge Z, Burns A, Harrison Dening K. ABC model: A tiered integrated pathway approach to peri and post diagnostic support for families living with dementia (Innovative Practice) Dementia. 2019 doi: 10.1177/1471301219838086 (E-pub ahead of print)

6. Bamford C, Poole M, Brittain K, et al. Understanding the challenges to implementing case management for people with dementia in primary care in England: a qualitative study using Normalization Process Theory. BMC Health Services Research 2014 14:549

7. Spenceley SM, Sedgwick N, Keenan J. Dementia care in the context of primary care reform: An integrative review. Aging Mental Health 2015;19(2):107-120

8. Tang E, Birdi R, Robinson L. Attitudes to diagnosis and management in dementia care: views of future general practitioners. International Psychogeriatrics 2016; 30(3):425-430.

9. Woods B, Arosio F, Diaz A, et al. Timely diagnosis of dementia? Family carers' experiences. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2018 https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4997

10. Koch T, IllIffe S. EVIDEM-ED project. Rapid appraisal of barriers to the diagnosis and management of patients with dementia in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Fam Practice 2010 1;11:52 doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-52

11. Frost R, Rait G, Aw S, et al. Implementing post diagnostic dementia care in primary care: a mixed methods systematic review. Aging & Mental Health 2020; DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1818182

12. Aldridge Z, Harrison Dening K. Admiral Nursing in Primary Care: Peri and post-diagnostic support for families affected by dementia within the UK Primary Care Network Model. OBM Geriatrics 2019;3(4):1-16

13. Quinn C, Clare L, McGuiness T, Woods RT. Negotiating the Balance: The triadic relationship between spousal caregivers, people with dementia and Admiral Nurses. Dementia 2013;12(5):588-605.

14. Martin A, O’Connor S, Jackson C. A scoping review of gaps and priorities in dementia care in Europe. Dementia 2018; Nov 29:1471301218816250. doi: 10.1177/1471301218816250.

15. Harrison Dening K. Admiral Nursing: Offering a specialist nursing approach. Dementia Europe 2010;1:10–11.

16. Harrison Dening K, Aldridge Z, Pepper A, Hodgkison C. Admiral Nursing: Case management for families affected by dementia. Nursing Standard 2017 31(24), 42–50.

17. Stockwell-Smith G., Moyle, W., Kellett, U., et al. The impact of early psychosocial intervention on self"efficacy of care recipient/carer dyads living with early"stage dementia—A mixed"methods study. J Adv Nursing (JAN) 2018;74(9):2167-2180

18. Bjorklof BH, Helvik A, Ibsen TJ, et al. Balancing the struggle to live with dementia: a systematic meta-synthesis of coping. BMC Geriatrics 2019;19: 295

19. Aldridge Z, Harrison Dening K. Dementia and comorbidities: a holistic approach. Practice Nurse 2019;49(10): 22-26

20. Gilhooly KJ, Gilhooly ML, Sullivan A, et al. A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatrics 2016;16:106.

21. Malthus K, Tranter S, Tiaki K. Supporting family carers of people with dementia. Nursing New Zealand 2018;24(10): 14-16.

22. Burgener S, Twigg P. Relationships among caregiver factors and quality of life in care recipients with irreversible dementia. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders 2002;16(2):88-102.

23. Rosness TA, Mjorud M, Engedal K. Quality of life and depression in carers of patients with early onset dementia. Aging Mental Health 2011; 15:299–306

24. Feast A, Moniz-Crook E, Stoner C, et al. A systematic review of the relationship between behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPSD) and caregiver well-being. International Psychogeriatrics 2016;28(11):1761-1774

25. Feast A, Orrell M, Russell I, et al. The contribution of caregiver psychosocial factors to distress associated with behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia. Int J Geriat Psychiatry 2016; https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4447

26. Aldridge Z, Findlay N. Norfolk Admiral Nurse Pilot Evaluation Report; 2014. https://dementiapartnerships.com/resource/norfolk-admiral-nurse-pilot-evaluation-report/

27. Illiffe S, Robinson L, Bamford C, et al. Introducing case management for people with dementia in primary care: a mixed-methods study. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64(628):e735-41 DOI: 10.3399/bjgp14x682333