Safety netting: why we must always do it

BEVERLEY BOSTOCK

BEVERLEY BOSTOCK

RGN MSc MA QN

Mann Cottage Surgery

PCN Nurse Coordinator, Hereford

Practice Nurse 2022;52(6):17–21

No matter how busy we are, it is vital that we make time to ensure that patients have the information they need so they know what to do if their condition changes

Safety netting is a process by which the uncertainty of a diagnosis, or the trajectory of that diagnosis, can be addressed to ensure that the patient and/carer in any given situation is made aware of the imperfect science of differential diagnosis and how unexpected developments need addressing. It is important that general practice nurses recognise the need for careful safety netting when delivering clinical care, whether in acute or long-term conditions. Failure to safety net adequately, and to fully document the advice that has been given, could result in catastrophic medical consequences for the patient and medicolegal risk for the nurse. As nurses struggle with increasing demands and limited resources, including time constraints, it is essential to make time to ensure patients have the information they need to be able to respond in an informed way to changes in their condition in order to access further advice in a timely fashion.

By the end of this article, the reader should be able to:

- Recognise what safety netting is

- Be aware of why it is so important

- Document safety netting advice effectively

- Implement sound safety netting advice

WHAT IS SAFETY NETTING?

In his seminal publication on consultation skills, Roger Neighbour recommended using three key questions to reflect on the process of making a diagnosis and addressing this with patients and carers in order to optimise safety netting.1 These questions are:

- If I’m right, what do I expect to happen?

- How will I know if I’m wrong?

- What will I do then?

In essence, safety netting aims to inform patients and/or carers about their condition and what to expect so that if the condition changes, fails to improve within the expected timespan, or deteriorates, they are alerted to the need to seek further support from the relevant healthcare professional. Safety netting may be especially important in the general practice setting as people are often presenting for the first time with symptoms which may span the entire breadth of clinical possibilities, from a minor, self-limiting illness, to the first manifestation of a significant, life-changing or life-limiting condition. At the early stages of an illness, with relatively non-specific symptoms, it may not be easy to know which of these is the case. Someone presenting with breathlessness, ankle oedema and fatigue may simply be suffering from the impact of obesity on their general wellbeing or may be presenting with a first episode of decompensated heart failure, so the clinician needs to be skilled in history taking, examination, safety netting and follow up. Even with the appropriate use of tests, there may be a delay in getting the results, meaning that safety netting will be even more important.

WHY IS SAFETY NETTING SO IMPORTANT?

Safety netting should be an integral part of the delivery of good quality care with a failure to safety net being seen as a failure to deliver holistic, person focused care. Jones and colleagues state that safety netting should be used as a consultation technique which helps to communicate uncertainty, provide patient information on red-flag symptoms, and plan for future appointments.2 Their recommendation was that safety-netting advice may help people to understand the anticipated course of the illness, recognise concerning symptoms and be clear about how and when to seek help. Jones recommended that safety netting was also important when considering the follow up of investigations and referrals and that children, people with acute illness, patients with multimorbidity, and those with mental health problems should be a priority for the provision of safety netting advice. Without adequate safety netting advice, key details may be missed, such as red flag symptoms or abnormal test results, leaving the patient exposed to the risk of deteriorating health and even death.

HOW SHOULD SAFETY NETTING ADVICE BE IMPLEMENTED?

Safety netting should be seen as being a key part of delivering care for acute illnesses, as the diagnosis may not be clear and there may be other possible differential diagnoses. However, it could be argued that every clinical consultation such as post vaccination or after an episode of wound care or following initiation of any new treatment, should include safety netting advice. When supporting people living with long-term conditions, advice often aligns to this idea of providing a safety net for the individual with the condition: this is why we offer self-management plans for people living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart failure and personalised asthma action plans for people who have a diagnosis of asthma. In many cases, safety netting advice is given in a generic way – ‘let us know if you have any side effects’ – and documented in a similarly generic way – ‘usual safety netting advice given’. Unfortunately, this is wholly inadequate, both clinically and medicolegally.

A study by Edwards and colleagues which looked at safety netting advice provision by general practitioners, showed that safety netting advice was more likely to be provided in acute conditions and that younger GPs were more likely to offer this advice than those aged 50 and older.3 The age of adult patients did not seem to influence the provision of safety netting advice.

The advice on safety netting should be specific to the individual patient and the specific complaint and although it takes time to provide and document tailored advice in every consultation, this constitutes safe practice. The patient and/or carer should be made aware of the possible scenarios that might occur, including red flags. They should be given clear advice on how soon to contact a healthcare provider including whether seeking advice urgently through out of hours care or via the emergency department would be appropriate. If out of hours care may be needed, it is important that they know how to access it. A follow up appointment can also be made proactively to ensure that the patient is reviewed. Jones states that the key components to safety netting are psychological (for example, legitimising repeat visits), cognitive (checking patient’s understanding), and informative (discussing red flags or other symptoms to be aware of).2 Recognising that people may present with more than one problem in a consultation, safety netting advice should be specific to each problem.

HOW SHOULD SAFETY-NETTING ADVICE BE DOCUMENTED

Jarvis points out that if an incident occurs which results in scrutiny of the medical records, it is essential that those records are as clear and specific as possible as they are likely to be the only version of events to which reference can be made and upon which medicolegal decisions can be made.4 Jarvis also recommends that as much relevant information as possible is recorded, including clinical findings, the plan of care going forward and how this was reached, the information given to patients, and any treatment prescribed. A digital record of the person completing the records and the date and time that this was done will also be made. In a previous article on documentation, we covered the importance of using a structured approach to history taking and documenting in a way that demonstrated the rationale for decisions around the likely diagnosis and the planned treatment strategy.5 The Montgomery Principle underlines how people should always be offered the opportunity to discuss whatever they feel they want to know and not just what the clinician thinks they need to know. Using techniques such as ‘Chunk and check’ and ‘Talk back’ reduces the risk of misunderstanding, especially if there are issues with health literacy.6,7

Edwards demonstrated that safety netting advice was not provided in all consultations where it might have been appropriate, and that documentation of the advice given was often inadequate. This could have significant medicolegal implications.3 Leaflets may be available that contain safety netting advice, but clinicians should not over-depend on these as patients may not read them. Nonetheless, there are some excellent resources available from providers such as Healthier Together: https://what0-18.nhs.uk/professionals/gp-primary-care-staff/safety-netting-documents-parents. A combination of verbal and written advice is ideal when offering safety-netting information and the resources used should be documented in the notes. Patient communication tools such as Accurx can also be used as a reminder of key safety-netting messages.

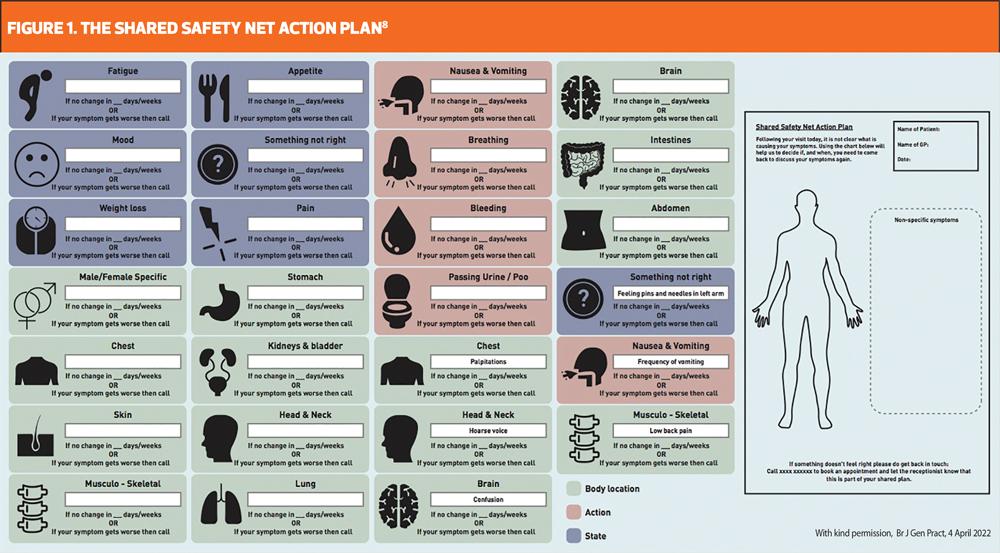

In a study which worked with patients and clinicians to develop a shared safety net action plan (SSNAP), a body diagram was developed to illustrate symptoms and a timescale for monitoring symptoms was agreed with the patient and illustrated on the charts (Figure 1).8 The SSNAP was saved into the clinical records and a copy was given to the patient. The patient could then be prompted at a later date to review their SSNAP and get back in touch if needed. This study, which involved patients, nurses and GPs, looked specifically at how to reduce the risk of missing a cancer diagnosis, although in theory it could be used for any type of safety netting.

SAFETY NETTING IN ACTION

A ’Who, why, when, where, what’ approach can be used for safety netting as using these simple words can trigger a reminder about what should be covered in the consultation as well as what should be documented:

- Why we need to safety net – explain the potential uncertainty around a diagnosis

- What symptoms to look out for – including new symptoms and signs of deterioration

- When to expect recovery – and what to do if recovery does not happen as anticipated

- Who to contact in the event of unexpected change – routine appointment or urgent care

- Where to get help - follow up in the GP surgery, out of hours care, emergency department

CASE STUDY: SAFETY NETTING AND FOLLOW UP

Harry, age 73, is a lifelong smoker who quit 6 weeks ago after suffering symptoms of cough and breathlessness. He reports that he’d had these symptoms for several months and that he put them down to his cigarette smoking. He woke up one morning coughing again, decided enough was enough, and he ‘just quit’. However, his productive cough and breathlessness has continued, and he decided to make an appointment to get some antibiotics. Harry was booked in with the nurse practitioner who took a thorough history and carried out an examination which left her with two key possible diagnoses: Harry could be presenting with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and/or he could have an underlying malignancy. She ordered some investigations including blood tests and a chest X-ray and booked Harry in for post-bronchodilator spirometry in two weeks’ time. She explained to Harry that from her initial assessment she thought he might have COPD and explained what this was. She discussed the importance of carrying out some tests, including the chest X-ray, and she explained why the chest X-ray was important in identifying other significant problems, which might include lung cancer. She gave Harry an opportunity to discuss his ideas, concerns and expectations and she explained the likely course of the condition over the next two weeks until he was reviewed. All of this was documented in the notes and written information was given to Harry to remind him of what had been said.

Using the ’Who, why, when, where, what’ approach in the consultation with Harry meant that the following advice was given and documented:

- Why we need to safety net – the nurse explained the reasons for her view that COPD was a likely diagnosis but that other conditions could be causing Harry’s symptoms

- What symptoms to look out for – Harry was advised that if he experienced any new onset symptoms such as haemoptysis, ankle oedema or nocturnal breathlessness, she would need to review him sooner and that he should make an emergency appointment on the day.

- When to expect recovery – Harry was advised that although there is no cure for his suspected COPD, the new inhaler should help with his symptoms but that the planned review was to see if this had been the case and to review his blood tests and chest X-Ray as well as carrying out another test to confirm the diagnosis.

- Who to contact in the event of unexpected change – the nurse explained to Harry that if additional symptoms occurred out of hours, it was important that he contact the out of hours service or go to the emergency department if the symptoms were severe

- Where to get help – the nurse checked that Harry knew how to access the GP surgery, out of hours care, and the emergency department

At the two-week follow up appointment, Harry was reassured that his tests were normal. His spirometry revealed an obstructive pattern supporting the diagnosis of COPD and ongoing treatment, education and support was arranged. Provision of a care plan for Harry, which includes support with self-management and advice on how to recognise an exacerbation and what to do, could be argued to be another form of safety netting.

SUMMARY

If it is accepted that safety netting is important both clinically and medicolegally, there needs to be clarity about how we safety net in primary care and how we document safety netting advice. Safety netting should be used to address the uncertainty faced by clinicians when making a diagnosis and to ensure that the patient and/or carer has the information they need to be able to recognise and act upon changes in their condition including red-flag symptoms. Ideally, safety netting should include booking in follow-up appointments where indicated, so that patients can be reviewed in a timely way and any results from investigations can be discussed. Documentation of the consultation, including using a structured approach to history taking, any examination carried out and investigations requested should be thorough as this may form the basis of any medicolegal case. Records will also be interrogated to identify safety netting advice given, so any advice should be specific to the individual and to each consultation. Safety netting is also important when managing long term conditions and self-management plans, developed through a shared decision-making approach, should support people living with long-term conditions have access to information which ensures that they know how to recognise unexpected changes in their condition and can manage those changes appropriately. In all of these situations, a structured approach to diagnosis and safety netting will ensure that the clinician is working as safely as possible and that the patient is supported with information and advice which keeps them from avoidable harm.

REFERENCES

1. Neighbour R. The inner consultation. 1987; Radcliffe Publishing Ltd, London

2. Jones D, Dunn L, Watt I, Macleod U. Safety netting for primary care: evidence from a literature review. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69(678):e70–e79 https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X700193

3. Edwards PJ, Ridd MJ, Sanderson E, Barnes RK. Development of a tool for coding safety-netting behaviours in primary care: a mixed-methods study using existing UK consultation recordings. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69(689):e869–e877. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X706589

4. Jarvis S. (undated) Playing it safe: safety netting advice https://mdujournal.themdu.com/issue-archive/issue-4/playing-it-safe---safety-netting-advice

5. Bostock B. Documenting your consultations. Practice Nurse 2021;51(9):12-14

6. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The impact of the Montgomery ruling; 2016 https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/members/membership-news/og-magazine/december-2016/montgomery.pdf

7. Health Education England. Health literacy: how to guide; 2020 https://library.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/08/Health-literacy-how-to-guide.pdf

8. Heyhoe J, Reynolds C, Bec R. The Shared Safety Net Action Plan (SSNAP): a co-designed intervention to reduce delays in cancer diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract 2021;0476. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2021.0476