Finding the evidence to support best practice

Liz Bryant

Liz Bryant

NP, MMedEd, BSc Health Sciences

Nurse practitioner in general practice, Practice Tutor Open University,

Trainer Education for Health

The evidence base for best practice is constantly being re-appraised and updated in light of new research. So how can you ensure that your own practice is up to date and in line with the latest evidence?

In clinical practice you will (or should) always have questions, and these will tend to generate further questions. This article considers how to manage daily queries about nursing practice in the complex interplay between evidence, resources, uncertainty and regulation. This is not an article with answers. Rather, it is intended to be a basis for reflection, for when you have questions in clinical situations but don’t have time to answer them, or don’t know where to look for those answers.

There are some underlying values, in line with the NMC Code of Conduct,1 which need to be taken into consideration when exploring the questions you have. In summary, good nursing care is a balancing act between the patient, the nursing team (with support from the family), the evidence, the wider clinical environment and available resources. Pragmatically, however, how can we continue to improve our effectiveness while ‘doing the day job’ and not running ourselves ragged?

In the context of this article – and for the sake of your working day – there are a couple of assumptions:

- You will only be accessing readily available evidence, and

- The answer to your question is not urgent.

If, however, your question turns into a quest for a definitive answer, and you pursue it further, then what you are doing is applied research, and primary care has great need of you!

EARWAX REMOVAL

Let’s start with an example that most practice nurses deal with on a daily basis.

What is the best agent to use to soften ear cerumen before ear irrigation (or sometimes to remove the need for irrigation)?

Olive oil is commonly advised. Sodium bicarbonate is sometimes regarded as superior for breaking the wax up. Many people swear by the morning shower directed into their ear canal, and others buy a diversity of oils and peroxides at the pharmacy. So how do you decide, and what is the evidence for any of these approaches?

You are likely to have at least one answer to this question in your practice guideline/protocol, but on what evidence is it based? And is it the same answer as that given by the local ENT department or audiology clinic? And how do you answer patient queries about over-the-counter products sold for a similar purpose?

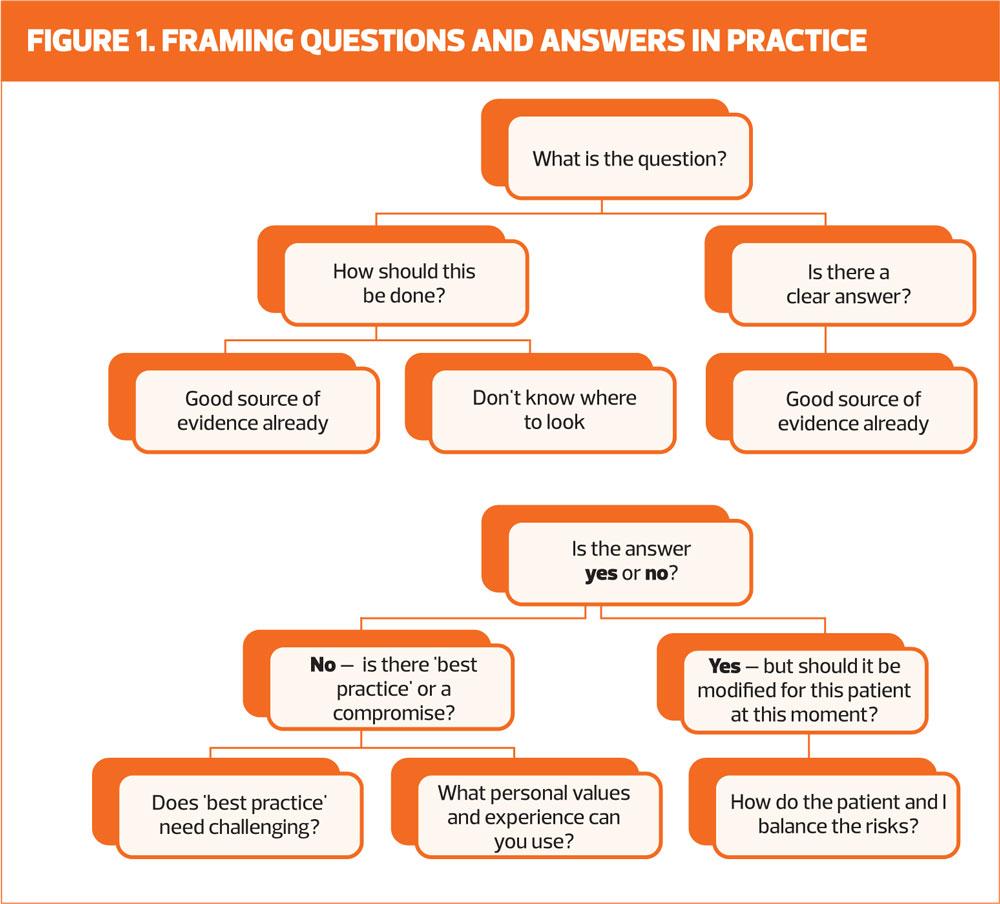

First, you need to frame the question (Figure 1).

In this case:

- What is the best agent for softening ear cerumen before or instead of ear irrigation?

Then:

- Do I know good sources of evidence?

By ‘good’ we mean up-to-date, high-quality and independent.

Local guidelines

Your local intranet may have guidelines for the management of a variety of conditions. These are likely to be based on national guidelines, e.g. NICE, RCGP and British Thoracic Society (BTS). The formulary for asthma management, for example, will have its roots in the SIGN/BTS guideline.2 These local guidelines are then adapted to local circumstances, and for most of your clinical questions looking at your local guideline is a reasonable first step.

There are, however some caveats. Your local intranet may not have been updated with the latest guidelines and, sometimes, economic considerations have produced a steer that is not effective for everyone. For example, some of you may have found that the choice of glucometers in your local formulary is too limited for your range of patients, or the choice of inhalers for asthma management is too prescriptive.

In the end, if the guidance does not appear to be based on independent evidence, you may have to dig deeper, and use the results of your search to justify your clinical decisions.

Other easily accessed sources

These include:

If these do not help, further evidence can be found by:

- Looking at NICE Guidelines to see what sources are used there, and following up likely leads

- Checking to see if there is a relevant topic in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

- Looking for an answer in BMJ Best Practice.

‘BMJ Best Practice’ produces clinical evidence provided by Cochrane Clinical Answers. This is linked to the BMJ website and can be accessed if you have an Athens Account (accessible from all four UK countries if you work for the NHS. Athens can provide you with excellent information on speciality areas such as respiratory or endocrine disease, and also produces brief, clear, patient leaflets.

You can use clinical journal articles to find possible references to follow up, but go for recent papers in journals such as the BMJ, Practice Nurse, Nursing Times and so on, that you can access easily, or – and this may be controversial – use Google Scholar to identify papers on the topic. That may be a jumping-off point or a dead end, so don’t be tempted to squeeze this exercise into a rare coffee break!

Is there a clear answer? Yes/no

In the case of ear wax removal the Cochrane review concludes there is no good evidence to support one wax-removing agent over another, or indeed to support any agent at all in the short term.3 So, is there a best practice/compromise, and on what values, experience and circumstances is it based?

The treatment should be easy to access and administer, with negligible risk of adverse effects. Water, olive oil and sodium bicarbonate might all be suitable and are easy to instil using a dropper bottle. You may want to discuss experiences with the team, and look at information from specialist centres such as Rotherham Ear Care.4 There is also a Health Technology Assessment,5 which concludes that much of the research is of poor quality, and there is not sufficient evidence to prefer one agent above another.

Modifying the answer

There may be reasons for modifying the answer you find to fit individual patients/circumstances. You will need to consider whether these are good reasons or whether they need challenging. You will also need to consider whether these are persistent reasons or whether they might need to be modified in time. Consider Case study 1.

The questions you ask should be simple so that you can search for them, and then introduce modifications when you apply the answer to a particular patient. In Case study 1, Ted’s situation might suggest a prescription for sodium bicarbonate drops because he can put them in himself with ease. The evidence suggests that they will be as effective as olive oil.

It is important, for legal reasons, to summarise the reason for your decision in the patient notes. You may want also to change your practice guidelines in the light of your research into the evidence.

OTHER COMMON QUESTIONS

There are several more clinical questions that crop up regularly:

- Why is B12 given intramuscularly rather than orally?

- What are the best dressing regimens for pilonidal sinuses, which often occur in young men who have to take weeks off work while they heal?

- Is there more than a theoretical risk of cross infection from Volumatic spacers (washed between patients) used for reversibility testing in general practice?

- What are the effective treatments for overgranulation/hypergranulation in wounds such as ingrowing toenail beds, and post-surgical wounds?

B12 injections

Wang et al,6 examined this question in 2018 – or at least tried to answer the review question about whether oral and injectable B12 were equally effective and tolerable. The evidence gathered in the systematic review was too poor to draw any useful conclusions, but they seem to be relatively equivalent.

HOwever, an earlier review7 suggests that in pernicious anaemia, where lack of intrinsic factor would intuitively suggest that oral B12 would not be absorbed, oral B12 is, in fact, as effective.

Primary care really needs better research here – imagine how many injections might be avoided!

Pilonidal sinuses

There is still debate about whether to stitch the wound or to allow it to heal by secondary intention. If a patient presents to you in your clinic with the latter option, do you pack the wound with a fibre ribbon, or cover with an absorbent occlusive dressing – or do something else?

In my practice we have packed these wounds for many weeks before they have healed. We have begun to ask questions about the impact of packing and ‘unpacking’ the wound at each dressing change on the delicate granulating tissue. This is a question that does not yield a quick evidence-based answer, but we had a pressing need to find one.

There was little to be found in Cochrane or CKS, but Google Scholar revealed a pilot study from 2015,8 that indicated superior healing and patient experience when the wound was not packed. In the absence of contrary evidence, and supported by our own misgivings, we are moving towards absorbent occlusive dressings with just a small piece of fibre ribbon in the open wound to prevent the reforming of a sealed cavity. (Case study 2)

Infection control and the use of holding chambers for reversibility testing

We use holding chambers – specifically, a Volumatic – for reversibility testing. We tried the disposable spacer, but they sometimes did not fit together or stay together well. I was specifically looking for evidence to support reverting back to Volumatics. I wanted data to suggest that the contamination risk was only theoretical.

The SIGN/BTS Guideline notes that static electricity in plastic spacers reduces the dose delivered to the patient.2 Paper disposable spacers do not generate static. In addition there were several papers readily available on Google Scholar that confirmed contamination of spacers with bacteria,9 some of which were capable of causing pneumonia. The contamination was much less likely if the spacers were washed and air-dried, but the possibility could not be ignored. My search for evidence therefore confirmed that we must return to disposable spacers for reversibility testing, and reinforced that we must explain the essential role of monthly cleaning of spacers for people who use them at home.

Over-granulation in healing wounds

This is another poorly researched area that causes distress, frustration and many expensive wound care sessions for both patients and staff. It affects capacity for work, mobility and patient self-esteem, as well as the more obvious demands on time and comfort. (Case study 3)

There are several papers in wound care journals,10-12 some of which promote particular products. The proposed causes of over-granulation, about which there is still uncertainty, are occlusive dressings leading to increased fluid in the tissues, or an inflammatory process due to infection or irritation.10 The consensus settles on:

- Reassessment at frequent intervals while reducing use of occlusive dressings

- Trialling topical steroid for no more than 7 days, and

- Having a low threshold for referral if there is any suspicion of malignancy.

Interestingly, a trial is ongoing to look at the role of steroid impregnated tape on overgranulation at peritoneal dialysis sites,13 where there is clearly a need for some answers.

WIDER ISSUES

What are reasonable risks and how can they be managed? The World Health Organization frames clinical risk management thus:14

‘Clinical risk management specifically is concerned with improving the quality and safety of healthcare services by identifying the circumstances and opportunities that put patients at risk of harm and then acting to prevent or control those risks.’

It is important to remember that harm can be done by over-investigating or overtreating, as well as by the reverse, under-investigating and undertreating. Harm can certainly be done by using biased evidence, or not tailoring the evidence to the circumstances. Risks are reduced by being clear about where your evidence is coming from, and documenting your reasons for a particular decision.

How much clinical uncertainty can we carry? A nurse experienced in wound care or in chronic disease management makes judgements using not only current evidence but also their past practice, and on the patient’s situation and insights. Together you will discuss the situation, bringing together your different expertise, and work out reasonable options based on that combined knowledge.

However, you are responsible for providing sound data in so far as they are available, and presenting the balance of risk and benefits between options. You are responsible for knowing about dressings, inhalers, healing and exacerbations in COPD. There is clinical certainty in very few situations so we have to live with risk in our professional lives, and continue to ask questions, seek better answers, and reflect on our practice and what it is teaching us.

REFERENCES

1. Nursing and Midwifery Council. 2018. The Code. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/

2. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, British Thoracic Society. SIGN 153 British Guideline on the management of asthma. 2016. SIGN/BTS. https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign153.pdf.

3. Aaron K, Cooper TE, Warner L, Burton MJ. Ear drops for the removal of ear wax. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018 Issue 7. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD012171.pub2/full

4. Ear Care Centre Rotherham. Ear irrigation guidelines 2017. Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust. http://www.earcarecentre.com/uploadedFiles/Pages/Health_Professionals/Protocols/Ear%20irrigation%20Guideline.pdf

5. Clegg AJ, Loveman E et al. The safety and effectiveness of different methods of earwax removal: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment 2010;14(28) https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/153113/1/mon1428.pdf

6. Wang H, Li L, Qin LL, et al. Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD004655.DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004655.pub3.

7. Chan CQH, Low LL, Lee KH. Oral vitamin B12 replacement for the treatment of pernicious anaemia. Frontiers in Medicine 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4993789/

8. Perera A, Perera AP, Howell AM, Sodergren MH, et al. A pilot randomised controlled trial evaluating post operative packing of the perianal abcess. Langenbecks Archives of Surgery 2015;400:267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-014-1231-5

9. Cohen HA, Cohen Z, Pomeranz AS, et al. Bacterial contamination of spacer devices used by children with asthma. J Asthma 2005;42(3):169-172 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1081/JAS-54625

10. Vuolo J. Hypergranulation: exploring possible management options. British Journal of Nursing 2010;19:6 (Tissue Viability Supplement)

11. McGrath A. Overcoming the challenge of overgranulation. Wounds 2011;7(1):42-49.

12. Hampton S. Understanding overgranulation in tissue viability practice. Wound care 2007; (9):24-30.

13. Central Registry of Controlled trials. Steroid-impregnated tape in the treatment of overgranulating peritoneal exit sites in renal dialysis. Cochrane Library. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-01479355/full?highlightAbstract=overgranul%7Cwithdrawn%7Covergranulation

14. World Health Organization. WHO Safety Curriculum Guide Topic 6. https://www.who.int/patientsafety/education/curriculum/who_mc_topic-6.pdf

Related articles

View all Articles