Be seen, be heard, be brave: nurse leadership

CAROL STONHAM,

CAROL STONHAM,

MBE, QN

Nurse lead and Vice Chair, Primary Care Respiratory Society UK

Senior nurse practitioner (Respiratory), Gloucester CCG

The traditional definitions of ‘nurse’ and ‘leader’ may explain why general practice nurses find it difficult or counterintuitive to take on leadership roles.But in the current challenging climate this may be exactly what they need to do

What is a nurse? The English Oxford dictionary1 definition is ‘A person trained to care for the sick or infirm, especially in a hospital’. The implication is of a compliant, submissive carer mopping the brow of the sick patient languishing in a hospital bed.

So maybe this is our first challenge – is this really the public perception of what is actually a massively varied group of highly skilled, well trained (often post graduate) group of professionals working in an extensive variety of settings? How often have we come across the person, or the nurse who refers to the skilled specialist as ‘just a nurse’? We are never ‘just a nurse’.

General practice nursing will soon reach crisis point, with Health Education England figures showing that 32% of practice nurses are already age over 55, and only 9% are under age 35. NHS England and NHS Improvement have workstreams focussing on recruitment, retention and retirement but the striking feature is that more nurses are considering retirement, attracted by the option of being able to draw their NHS pension at age 55 under the older pension scheme.

Issues around pay are not the predominant reason for leaving the profession. The NMC surveyed more than 4500 leavers in 2017 to explore their reasons for leaving the profession.3 Pay did not feature in any of the top reasons. Excluding retirement, 44% cited working conditions including issues such as staffing levels, and being moved from place to place, 28% had a change in personal circumstances, and 27% were disillusioned with the quality of care they were able to offer. In most of these cases the nurses clearly did not feel they were in a position to be able to influence things to make improvements, or had tried and been unsuccessful.

Is this reflective of working in primary care? Are these issues familiar or are we in a different environment where our challenges come from different sources?

The primary health care team can be a cohesive, supportive way of working yet it can still feel isolating when you are the lone voice for nursing, the lone voice for high quality respiratory care, or it feels like you are the lone voice representing the patient in among the demands of ticking boxes, running to time and the general and increasing demands of working within a strained health care system.

Despite being part of the team, once the door to the consulting room is closed, it feels as if you are a lone worker and for those working in community settings, once the car door closes en route to the first visit that is exactly the case.

Who do you turn to when you encounter professional dilemmas? How do you access good quality training to continue your career development? How do you feel when you review a patient and aren’t sure they have been diagnosed correctly?

‘KNOWING YOURSELF IS THE BEGINNING OF ALL WISDOM’

Aristotle 382BC – 322BC

The starting point of a journey to improving communication and confidence is gaining a better understanding of yourself. Most of us feel we know what makes us tick but it is worth looking a little deeper below the surface. There are many personality tests available online that usually involve completing a short questionnaire before your results are revealed. Myers-Briggs4 is well established and breaks the results down into 16 personality types. More user-friendly versions using four colour classifications are also useful and can be reasonably quick to assess.

Although everyone will cross over into more than one personality type and may alter in different situations most people will have one type that is more predominant than the others. Recognising the strengths and weaknesses of your personality type helps to understand how and why you react in different situations. They can reveal a few surprises.

Further self-understanding can be developed in considering our favoured learning styles. VARK5 also uses four categories. The learning styles are visual, auditory, reading/writing and kinesthetic, and there is acknowledgement that some learners will not fall into one distinct category but will have a mixed learning style.

‘ALONE WE CAN DO SO LITTLE; TOGETHER WE CAN DO SO MUCH’

Helen Keller 1880 – 1968

When we apply the understanding of personality types to those we work with the structure of the team and the importance of the parts we play becomes clearer. There is a reliance of those around us to step up where we are weaker and fill the gaps in our personal preferences with their stronger characteristics. A mixture of personality types complement each other and provide a more rounded structure to the team.

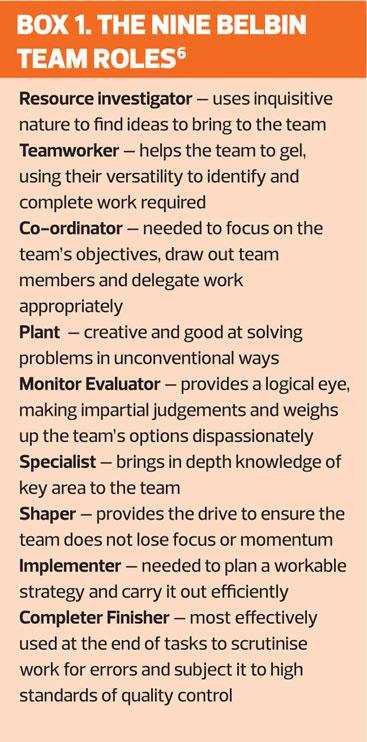

Another interesting method of describing team behaviours is described by Belbin.6 The Belbin Team Roles method has identified nine different clusters of behaviours that are displayed in the workplace (Box 1). Each of the roles described also includes a description of the strengths and allowable weaknesses of the role. Effective teams need a mixture of the behaviours, although all nine are not essential. Each role within the team will have strengths and weaknesses. Knowing where these strengths and weaknesses allow the team to work effectively.

‘NO ONE CAN MAKE YOU FEEL INFERIOR WITHOUT YOUR CONSENT’

Eleanor Roosevelt 1884 – 1962

A better understanding of the inner workings of our personality gives us more insight into how we interact with family and friends, and with colleagues and teams in the workplace. It might also help equip us with some techniques in handling situations in a different way if we understand where the other person is coming from – their personality type or team role may be in stark contrast to ours which can be complementary or antagonistic.

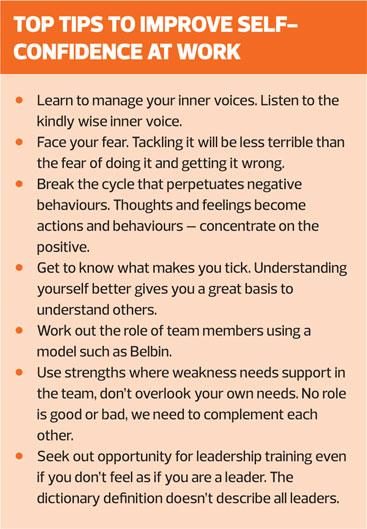

But there may be times when personal confidence is lacking: the tricky situation, the difficult conversation, the time to challenge the diagnosis. It may fill you with dread even when you are armed with the evidence, or it has to be done, or it is in the patient’s best interest.

Jo Emerson, confidence coach, tackles confidence building in her book ‘Flying for beginners’.7 Emerson explains that we all have different voices offering constant dialogue inside of us and it is for us to decide where our focus is. The voices, once described, usually become familiar and are rooted in the Berne theory of transactional analysis.8

One voice Emerson describes is the critical, overbearing voice that is constant in highlighting our short fallings and weaknesses. This can be related to the critical parent in Berne’s model, the voice that monitors adherence to rules – the ‘shoulds’ and ‘musts’. This voice is often loud and constant, giving internal negative dialogue.

When one becomes tuned into the voice of negativity, the result is a feeling of never quite being good enough or achieving potential. The internal feelings are that of a child being scolded by a critical parent. Berne described this as the child ego. Self-confidence is negatively affected over time if one is unable to break free from this cycle yet many of us are unaware that it is even happening.

Another voice, the voice of wisdom, is often the quieter internal voice and needs ‘tuning into’. It is the kinder voice, the voice you would use if you were speaking to someone else. Why, then, do we often opt for the harshness of the critical parent when we are listening to our inner dialogue and ignore the kind voice of wisdom? Emerson explains that the answer is to become familiar with the kinder softer voice and listen to what it has to say in favour of the nagging of the critical parent. It takes time and practice to give it preference, but Emerson believes that quietening your inner critical voice you give you the confidence to find your outer voice.

The other big factor that affects self-confidence, Emerson suggests, is fear. It may be fear of failure, being made to look foolish, not being listened to, being judged, the list is endless. But what she also says is that fear is normal, everyone is afraid some of the time but managing fear not allowing it to control us will allow us to be confident in what we do.

Fear is a powerful emotion. The thoughts and feelings associated with fear become actions and behaviours which further support the thoughts and feelings and perpetuate the cycle. Often the fear of something is worse than the reality of that from which the fear stems. Emerson uses a popular acronym, False Evidence Appearing Real when helping clients break the cycle of fear.

‘BE THE CHANGE THAT YOU WISH TO SEE IN THE WORLD’

Mahatma Gandhi 1869 – 1948

So what of leadership in practice nursing? Most leadership training includes the detail contained here in more depth and breadth but is such training readily available to nurses working in general practice and community settings or should it be included as part of the core curriculum for general nurse training? Funding for disease specific education can be difficult to access with nurses often having to undertake training in their own time and sometimes having to fund the course fees themselves.9 Leadership training will have a positive effect on clinical decision making, patient advocacy, job satisfaction and therefore one could foresee improved recruitment and staff retention in clinical roles. But will it be seen as a priority in a health care system that is overstretched where funding is under constant scrutiny and where there are always competing priorities?

Leadership training allows those that undertake it to gain a better understanding of themselves and those around them, how they fit into a team and how teams function and why sometimes they don’t. It introduces the wider healthcare system, which can be difficult to grasp when working in the periphery of general practice. Candidates experience the wider concepts of leadership and how they can take on a leadership role even though the title of leader can feel quite alien. Leadership lessons learned from the Canadian Geese10 describes the role of the leader as one that allows for change and flexibility, where the team member at the helm changes over time therefore allowing each team member the opportunity to take leadership responsibility and for periods of rest and reflection between.

Another model of leadership that frequently resonates with nurses in practice is described in a report by The King’s Fund. Compassionate Leadership11 is a style of leadership that ‘enhances the intrinsic motivation of NHS staff and reinforces their fundamental altruism. It helps to promote a culture of learning, where risk-taking (within safe boundaries) is encouraged and where there is an acceptance that not all innovation will be successful – an orientation diametrically opposite to a culture characterised by blame, fear and bullying. Compassion also creates psychological safety, such that staff feel confident in speaking out about errors, problems and uncertainties and feel empowered and supported to develop and implement ideas for new and improved ways of delivering services. They also work more co-operatively and collaboratively in a compassionate culture, in a climate characterised by cohesion, optimism and efficacy.’ This is something all nurses, in fact all health care professionals, can relate to.

CONCLUSION

Nursing in the current economic and political climate is challenging. It is a profession that sits at the centre of delivery of health care but has a quiet voice rather than a collective roar. Nurses are not surging forward in their droves to attend leadership training – and this appears to apply particularly to nurses in general practice.

Maybe it comes back to the dictionary definition again.1 ‘Leader – The person who leads or commands a group, organization, or country’. It is no wonder nurses are not recognising themselves as leaders. The traditional leader, the vision of the person giving orders, in current leadership styles such as the Canadian Geese, is outdated. The styles of leadership coaching offered now will allow you to better know yourself and your team, improve your confidence and enhance your clinical skills and patient advocacy. It also helps develop skills to build personal resilience. That is a far more attractive offer.

Accessing training might be easier than it sounds too. Ironically negotiating time and funding for training requires confidence and a knowledge of what will appeal to the commissioner or manager yet those are the skills leadership training imparts. Training is available from a variety of sources. The Primary Care Respiratory Society UK runs a Respiratory Leadership programme that takes place twice a year and is a rolling three-year programme. It includes leadership skills as well as an introduction to project management and quality improvement, and is free to join.

Our challenge as practice nurses is to step up to the challenge. We may not see ourselves as a leader as the dictionary defines it but the skills we can gain through the coaching of a leadership programme will give confidence and understanding which will allow us to become one of the geese rather than one of the followers. Then maybe the next challenge is to rewrite the definitions.

REFERENCES

1. English Oxford Dictionary 2018, English Oxford Living Dictionary, viewed 12 July 2018, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/nurse

2. Cummings J (2018) ‘The Chief Nursing Officer for England’s Vision for Nursing’ The Queen’s Nursing Institute. Unpublished.

3. NMC 2017, The NMC Register 2012/13-2016/17. https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/other-publications/nmc-register-2013-2017.pdf

4. The Myers & Briggs Foundation. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) original research. https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/original-research.htm?bhcp=1

5. VARK Learn Limited. A guide to learning styles, 2018, http://vark-learn.com

6. Belbin Associates. The Nine Belbin Team Roles, 2018. http://www.belbin.com/about/belbin-team-roles/

7. Emerson J. Flying for beginners: a proven system for lasting self-confidence. http://jo-emerson.com/products/flyingforbeginners/

8. Berne, E. Transactional analysis in psychotherapy. New York; Grove Press: 1961

9. The Queen’s Nursing Institute. General Practice Nursing in the 21st Century: A Time of Opportunity, 2016. https://www.qni.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/gpn_c21_report.pdf

10. Muna F, Mansour N. Leadership lessons from Canada geese. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 2005;11(7-8)316-326. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527590510635189

11. West M, Eckert R, Collins B, Chowla R. Caring to change. How compassionate leadership can stimulate innovation in healthcare. The King’s Fund, 2017.

Related articles

View all Articles