Understanding general practice

Sheinaz Stansfield MBA

Sheinaz Stansfield MBA

Oxford Terrace and Rawling Road Medical Group, Gateshead

Practice Nurse 2022;52(1):10-13

Understanding the nonclinical systems and processes in general practice that provide a foundation to clinical service delivery is essential knowledge for GPNs, especially those new to general practice

Many practices function as small businesses, albeit some may have remodelled to have the operation functions provided by a federation or may have integrated their back office functions in a scaled up model. For this reason, it will be important for nurses new to general practice to spend some time with practice manager (PM) as part of their early induction. Understanding the nonclinical systems and processes in general practice that provide a foundation to clinical service delivery is essential knowledge for general practice nurses (GPNs) to help understand how the rest of the team functions.

PMs deal with the day-to-day management of the practice and with its business elements and processes. Processes are concerned with planning, budgeting, organisation, staffing control and problem solving.

Management functions in general practice have evolved as new models of care have emerged, with the general practice model evolving from a simple ‘cottage industry model’ to a ‘corner shop model’, and now a scaled-up ‘supermarket model’ of practices working together in primary care networks (PCNs).

Most practices are owned by GPs, but with the review of the GP Contract in 2019, the partnership model is starting to change, with the inclusion of nurses, allied health professionals and other non-clinical partners. Responsibility for the delivery of management functions varies across practices, depending on the structure, culture and leadership style of the organisation. Predominantly, practice management functions are determined by senior partners who are usually the business owners.

BACKGROUND

In the UK, general practice has emerged from a pattern of services established by the National Insurance Act, 1911. Initially the ‘list’ included only those who were able to make national insurance contributions. In 1948, when the NHS was established, it was extended to the whole population. GPs retained their lists as part of their independent contractor status in the NHS, self-employed individuals delivering services on behalf of the NHS but not subject to the same terms and conditions of employment as NHS staff.

The first GP contract, the ‘Charter’, was introduced in 1966, and later the 1990 Contract introduced schemes to promote early intervention and prevention. Practices started to become more complex organisations, with the introduction of ancillary staff – receptionists and practice nurses – forming the early Primary Health Care Team.

General practice has been recognised as an essential ingredient of a cost-effective health service, managing up to 80% of health care needs. In the late 1990s, general practice received 11% of gross domestic product (GDP) but by 2019, this had reduced to 8% GDP despite increasing demand and complexity of population need.

EXTERNAL ORGANISATIONS

Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs)

CCGs, introduced by the Health and Social Care Act in 2012, are clinically led statutory bodies responsible for the planning and commissioning of health care services for their local area. Since 2013, all practices have been required to be a member of a CCG. Individual practices remain independent organisations, but profit, contractual and pension arrangements will vary according to the type of contract they hold.

Primary Care Networks (PCNS)

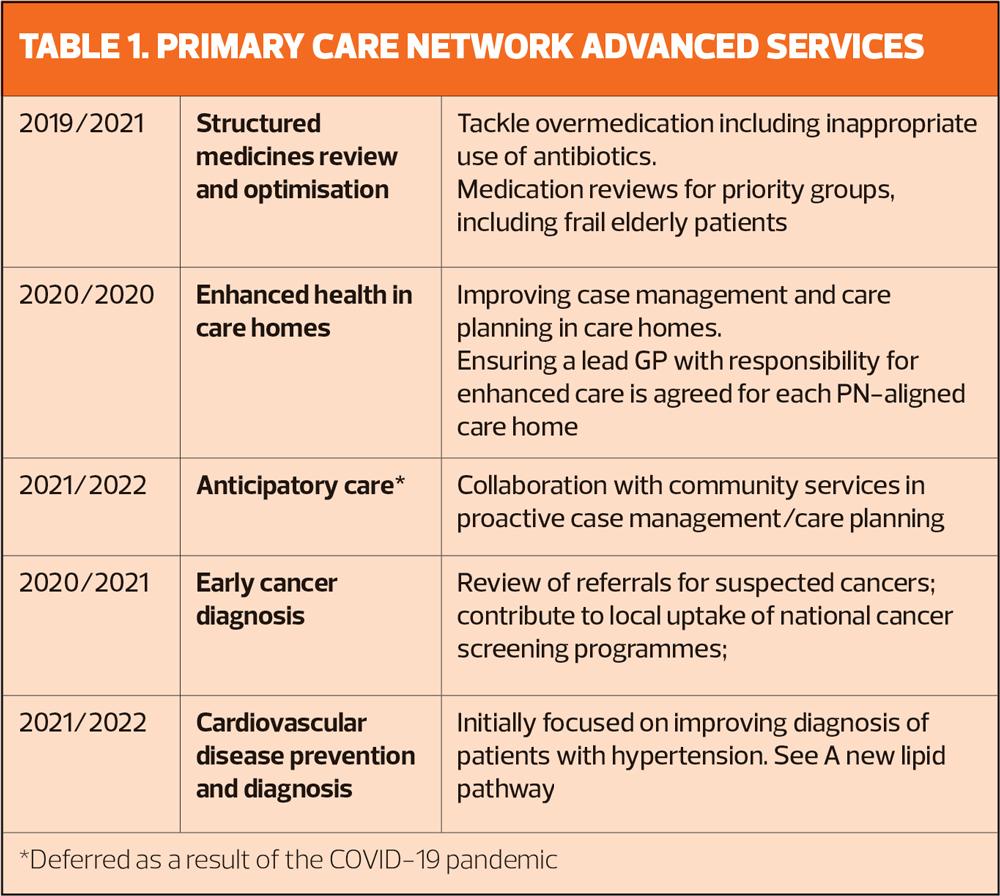

PCNs were introduced in 2019 to provide a more formal structure around the variety of ways general practices work, but without creating new statutory bodies. PCNs are an attempt to scale up practices through collaboration, and manage populations of between 30,000 and 50,000 people. PCNs have responsibility for delivering national service specifications – See Table 1.

Integrated care partnerships (ICPs)

ICPs are collaborative networks of care providers, healthcare professionals, community providers, voluntary organisations, patients, carers and service users. The role of ICPs is to design and coordinate delivery of local health and social care services. This ‘locality-based’ integrated style of working covers populations of between 150,00 to 500,000 people, and will be the vehicle for partnership working between the NHS and local authorities. As general practice scales up through federations and PCNs, they will also have an active role in planning and designing care at population level.

PROVIDER LANDSCAPE

Individual practices

The business structure of general practice has changed little since the inception of the NHS. Essentially, practices are run by clinical partners in a vertical structure. Changes in the GP contract have sought to stimulate working within a broader primary healthcare team; however, in many practices senior partners control and maintain decision-making power.

Federations

The BMA describes a federation as a group of practices working together within their local area, in a locally agreed collective legal or organisational entity. As a provider organisation, federations provide economies of scale to help sustain individual practices by managing workload and coordinating services across a geographical area. Operational and administrative processes can be standardised to reduce workload and save money, through joint provision of functions such as human resources (HR) and payroll. Staff, whether clinical or operational, can also be employed through the provision of services, facilitating sharing of good practice.

CONTRACTING AND FINANCE

There are three main contractual options for the delivery of primary medical services:

- General medical services (GMS) contracts: deliver core medical services, agreed nationally between NHS employers and the BMA. Core funding (the ‘global sum’) is based on the practice’s registered list size and adjusted for local demographics. It includes reimbursement of staff employment costs.

- Personal medical services (PMS): as above but including extra health services to address specific local health needs, e.g. services for homeless people

- Alternative provider medical services (APMS): a contract between the NHS and alternative providers, e.g. private health companies and social enterprises to provide essential and additional services

Direct and local enhanced service (DES, LES)

In addition to the core contracts described above, additional services are contracted through DES and LES. A DES is a nationally negotiated service, over and above that provided by the core contracts. An LES is locally negotiated and commissioned by the CCG or local authority to meet local needs and may include services such as contraception and smoking cessation.

ORGANISATIONAL CULTURE

The culture of an organisation is a central part of the strategy to achieve success or excellence. Every organisation has a culture, whether it is designed or evolves through neglect, accident or omission. In some practices, a command and control culture has been perpetuated in alignment with vertical organisational structure and the senior partner model of leadership.

With the introduction of PCNs, a different, more collaborative culture and leadership style will be key to success. While shared values, beliefs and a collective interest in building an organisation are key elements, the behaviour of senior managers is an essential factor in developing the culture of the organisation.

A strong culture is evident in practices where all members have a shared understanding of the core beliefs and values of the organisation. Internally, culture provides the ‘glue’ that binds the organisation together. It is practices with this culture and collaborative leadership style that are forging the way forward towards successful new models of general practice.

QUALITY MANAGEMENT

The NHS quality agenda is built around three components, identified in Lord Darzi’s 1998 report, High Quality Care for All:

- Patient safety: reducing adverse impact on patients and preventing medical and systems error that may lead to unsafe care or harm to patients

- Clinical effectiveness: the extent to which specific clinical interventions do what they are intended to do (i.e. maintain and improve the health of patients and secure the greatest possible health gain from the available resources)

- Patient experience: treating patients with dignity, respect and compassion, ensuring that the patient receives the best possible experience of care and recovery.

CCGs use a range of quality improvement measures including NICE guidelines, quality dashboards, clinical commissioning information systems and audit to measure quality in general practice. In addition, practice have become financially accountable through the introduction of quality outcome indicators (See Quality and Outcomes Framework).

QUALITY ASSURANCE

Care Quality Commission (CQC)

The role of the CQC to drive improvement in the quality of health and social care standard. Since 2013, general practice has been legally required to meet ‘essential standards of quality and safety’ [and to be registered with the CQC as a provider]. The CQC carries out inspections to ensure practices are compliant, and rates practices’ performance against its standards – a process that practices have found to be resource-intensive and onerous.

The CQC has the power to address poor practice. Where providers are found not to be meeting minimum quality standards, the CQC has the power to issue warning notices, penalties, suspension or restriction of activities. In extreme cases, this has resulted in the closure of some services.

A key role for nurses is to ensure that policies and procedures relating to clinical systems (such as infection control) are in place and implemented in preparation for CQC inspections.

Quality and Outcomes framework (QOF)

QOF was introduced as part of the 2004 GP Contract in an attempt to align regards and incentives to quality improvement, and included both clinical and managerial indicators.

Participation rewards general practices for implementing good practice in their surgeries, and although voluntary uptake has been virtually universal. For most practices, QOF is the only area where practices can make a difference to their income, and most practices derive a significant proportion of their income through QOF. GPNs have a lead role in managing long term conditions and the other clinical requirements of QOF, and therefore have an important role to play in planning, delivering and also ensuring appropriate claiming for services delivered.

QOF points and indicators are revised and negotiated by the BMA annually. The criteria or indicators are designed around best practice and are assigned a number of points for achievement. At the end of the financial year, the total number of points achieved by the practice translates into payments.

QOF indicators are grouped into different domains.

- Clinical: the clinical element awards points for achieving specified indicators. The formula includes the number of patients and the numbers diagnosed with certain common chronic illness. The value of points includes the prevalence of a condition in the practice; increased case finding attracts additional funding. Those that nurses contribute to include management of common conditions e.g. asthma, diabetes, cardiovascular disease

- Public health: Management of major public health concerns such as smoking and obesity; vaccinations and immunisations; screening; and blood pressure checks

- Quality improvement: Indicators focus on early cancer diagnosis, and care of people with learning disabilities and require the contractor to demonstrate continuous quality improvement activity in these area, and participation in network activities to share and discuss learning from these activities.

PAY, AND TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF EMPLOYMENT

It is important for new GPNs to be aware that general practices, as independent organisations, have no formal mechanism for agreeing pay and conditions for nursing and administrative staff. Many practices have taken some aspects of the NHS Agenda for Change and adapted them for their staff, but this will differ from practice to practice. Most GPNs will negotiate their own pay and terms and conditions of employment, which has led to wide variation across general practices.

PMs manage human resources in practices [unless these are centralised in a federation]. HR management is concerned with management of employees in the practice and includes the development of organisational policies and procedures. Key components include employee recruitment, retention, training, development, conditions and remuneration.

CONCLUSION

Nurses new to general practice will be mainly concerned with the clinical elements of their work in the general practice setting. Understanding the business elements and workings of the practice helps GPNs develop an appreciation of the organisation they work in, and to contribute to the business.

The general practice model has evolved from a corner shop model to the supermarket model over a period of four decades. However, individual practices continue to function on a continuum between the two models. Management functions have also evolved to meet the business needs of organisations that are growing in a variety of formal and informal structures. As the NHS environment in which general practices exist becomes more complex and challenging to navigate, management too must evolve from administrative to operational and increasingly strategic to function across a wider system.

A workforce crisis has arisen in the NHS because of changing demographics, increasing complexity of illnesses and people living longer with two or more long term conditions. This, along with changing NHS architecture, has resulted in increased pressure on general practice and is making the GP partnership model less favourable, with many GPs now choosing portfolio careers. This crisis has been the catalyst for new models of care and integrated working, with an increased focus on practices collaborating and working together to manage a reduction in resources.

GPNs have, to date, worked in isolation. This catalyst for change will require GPNs to develop new skills, particularly focused on case management and personalised care planning, to function as members of a broader primary health care team, taking multidisciplinary approaches to manage changing demographics and patient needs.

Changing population needs and the aforementioned workforce crisis have also brought recognition that patients’ needs cannot be managed by GPs alone in a 10-minute appointment. The valuable role of GPNs is required more than ever and complements the new roles that are being introduced. This constitutes a move away from managing patients’ conditions through reactive processes to managing the person through proactive, person-centred and personalised care – an area in which nursing has much to offer.

Nurses have worked in general practice since the 1990s in extended roles, although their development needs have not had national exposure until relatively recently. The NHS England and NHS Improvement GPN Ten Point Plan recognises the ability of general practice nurses to transform care and address workforce challenges to deliver an NHS fit for the future.

Through exposure to quality improvement and new models of care, general practice is going through a transformation in structure, culture and leadership style. This, coupled with multidisciplinary working and training, will make general practice a more desirable first destination career choice for nurses.